But how much of this story is real, and how much of it is just mythologizing?

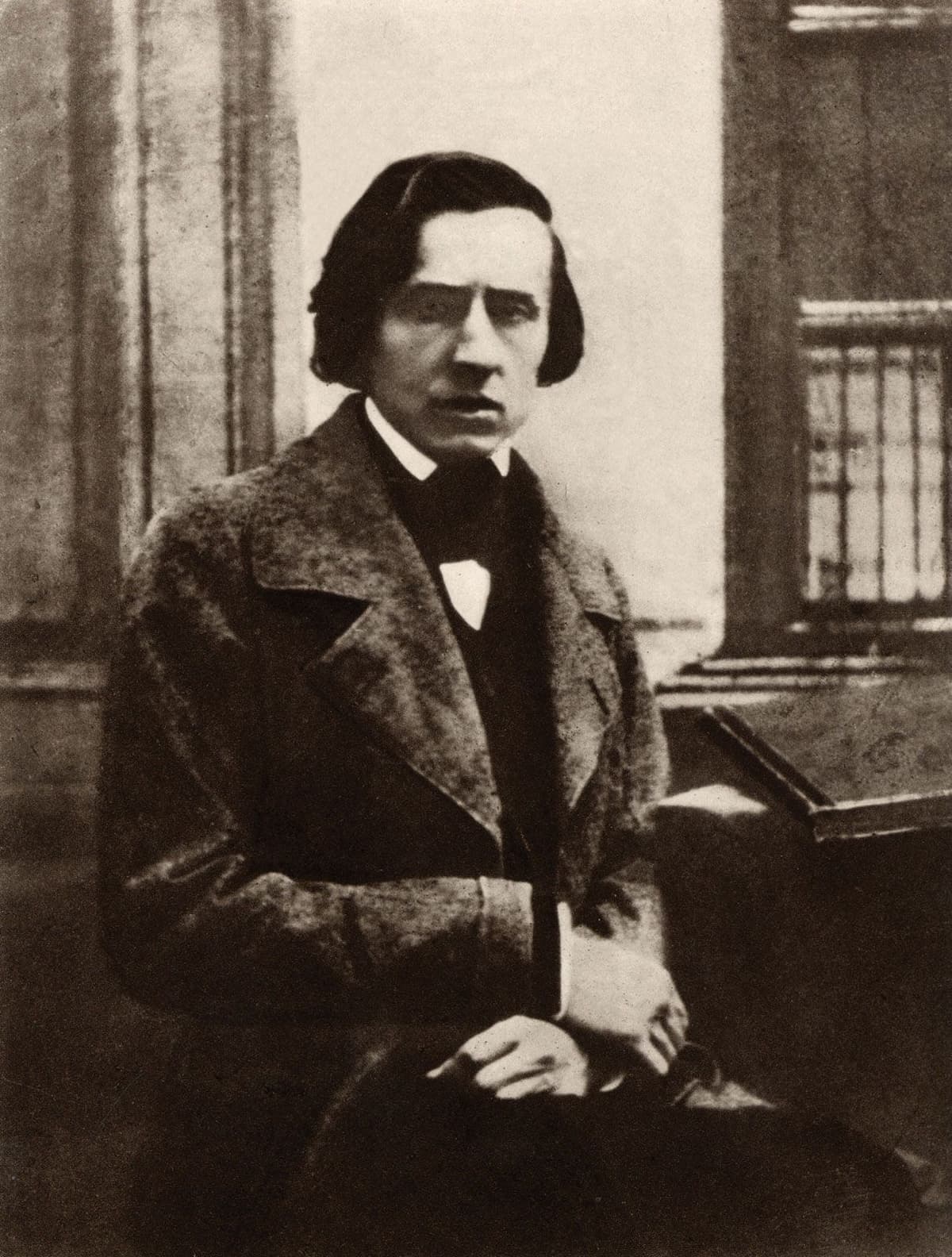

Today we are looking at the real story behind the love affair between George Sand and Frédéric Chopin.

George Sand’s Childhood and Marriage

George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil was born on 1 July 1804 in Paris.

As a girl, she lived with her grandmother at the family manor house in Nohant, roughly three hundred kilometers from Paris.

In 1821, her grandmother died, and Aurore inherited the manor. The house at Nohant became a home base for her throughout her life.

In 1822, at the age of eighteen, Dupin married a man named Casimir Dudevant, whose biggest accomplishment in life ended up being George Sand’s ex.

They had two children together: a son named Maurice in 1823 and a daughter named Solange in 1828. (That said, Solange’s paternity is questioned.)

After almost a decade, the marriage deteriorated. Mrs. Dudevant left her husband in 1831 and, scandalously, began seeing other men. In 1835, she separated from him legally and took custody of her two young children.

George Sand’s Writing Career

In her twenties, the former Mrs. Dudevant embarked on romantic relationships with a wide variety of accomplished artistic men, including novelist Jules Sandeau, writer Prosper Mérimée, dramatist Alfred du Musset, and others. (She also developed intense romantic feelings for actress Marie Dorval. The two would remain friends for the rest of their lives.)

The former Mrs. Dudevant’s writing career began in the early 1830s, when she began collaborating on stories with her lover Jules Sandeau. They signed their joint efforts “Jules Sand.”

It quickly became obvious that she was a very talented writer. In 1832, at the age of twenty-eight, she wrote a novel on her own and published it under the pseudonym George Sand.

It wasn’t long before this divorced mother of two was one of the most respected authors in Europe. Her work was actually more popular in England than either Hugo’s or Balzac’s!

As her career progressed, she didn’t restrict herself to just novels: she also wrote literary criticism, theatrical works, political commentary (she was a socialist), and more.

The Meeting of George Sand and Frédéric Chopin

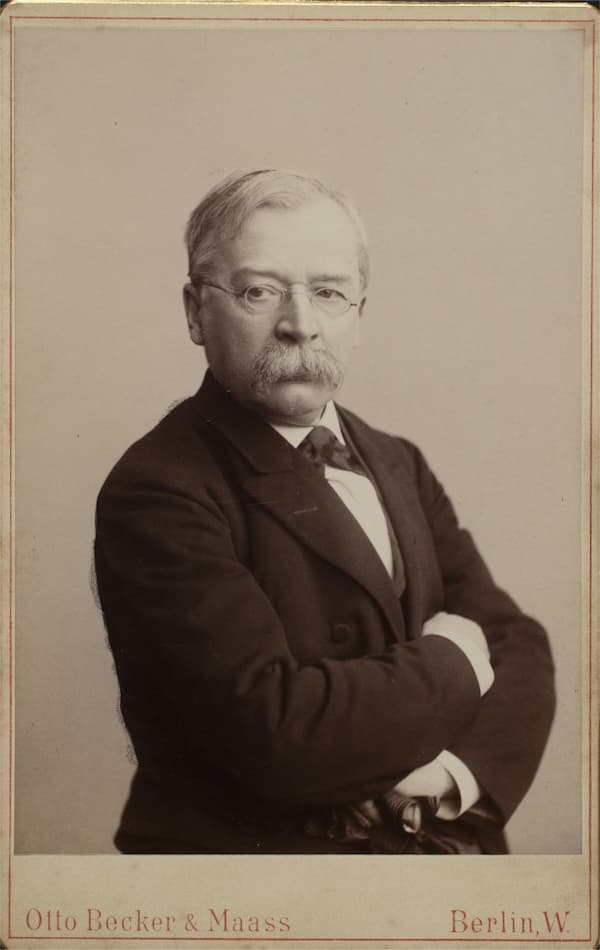

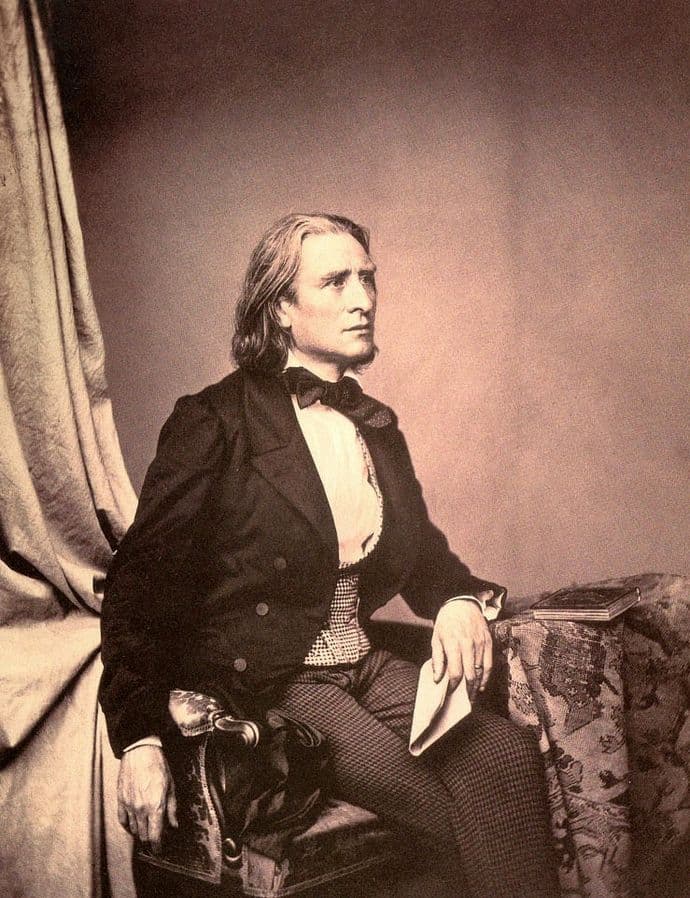

Josef Danhauser: Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano

Apparently, Sand was intrigued by Chopin even before they met. It is believed she encouraged their mutual friend Franz Liszt to arrange an introduction.

On 24 October 1836, in the salon of fellow author (and Liszt’s mistress) Marie d’Agoult, George Sand and Frédéric Chopin met each other for the first time.

Chopin was initially repulsed by Sand, reportedly asking Liszt, “Is she really a woman?”

Despite this rocky first impression, Sand still remained intrigued by him.

It seems they were not close before 1838. In May of that year, she asked a mutual friend in a letter if he was still engaged (at one point, he had been betrothed to his former pupil Maria Wodzińska). If so, Sand wrote, she would back off. However, it turns out that the relationship with Wodzińska was well and truly over.

It’s unclear exactly how, but eventually Chopin and Sand became friends, and then lovers.

Their Trip to Majorca

To celebrate their new partnership, Sand planned a trip to Majorca, Spain, over the winter of 1838. She was hopeful that the change in climate would help Chopin’s declining health.

The trip started off on a high note. “The sky is like turquoise, the sea is like emeralds, the air as in Heaven,” he wrote in a letter.

Chopin ended up composing some of his best-known works in Majorca, including his 24 Preludes. The work tied most closely to this place in time is undoubtedly the Raindrop Prelude, said to be inspired by the rain dripping off the eaves of their lodgings.

Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in D flat major Op. 28 No. 15

The trip became a struggle when, as the Raindrop Prelude suggests, the winter weather turned damp. Instead of improving, his health deteriorated. The couple’s gloomy accommodations didn’t help matters: they had sought refuge in a deserted monastery in Valldemossa.

Soon Catholic locals began viewing the unmarried divorcée and her invalid partner with suspicion. The couple’s reputation grew even worse when rumors spread that Chopin’s cough would spread communicable disease. In the end, the locals grew so impossible to work with that Sand was eventually forced to lug a handcart to the capital city of Palma just to load up on basic supplies.

Their nightmare came to an end ten weeks after they arrived, but unfortunately their return voyage to Barcelona occurred during rough seas, and Chopin suffered from seasickness on the way home.

Life in France

Portrait of Frédéric Chopin and George Sand by Eugène Delacroix

A much more agreeable destination turned out to be Sand’s country home in Nohant. Chopin and Sand settled into a schedule of spending half the year in Nohant and the other half in Paris (albeit in separate apartments).

Although they never officially moved in together full-time, in 1842, they did take the step of renting adjacent apartments.

Chopin ended up writing many great works at Nohant. Today the home is a museum.

The Breakup

So why did these two titans of the Romantic Era break up?

One blow was Sand’s novel Lucrezia Floriani, which starred a sickly Eastern European prince being cared for by Lucrezia, the protagonist. The Polish Chopin grew increasingly resentful of this particular creative choice, feeling that his health troubles had become nothing but grist for Sand’s creative mill.

A second blow came when Chopin sided with Sand’s daughter, Solange, in various fierce mother-daughter arguments. Sand interpreted Chopin’s loyalty to Solange as his being in love with her. It didn’t help matters that Sand’s other child, Maurice, didn’t like Chopin, either.

Ultimately, after almost a decade together, the two great artists split up for good.

On July 28, 1847, Sand wrote to him: “Goodbye, my friend. May you soon be cured of all your ills, as I hope that now you may be…. If you are, I will offer thanks to God for this fantastic ending of a friendship which has, for nine years, absorbed both of us. Send me your news from time to time. It is useless to think that things can ever again be the same between us.”

Backlash to the Breakup

Sand herself predicted the backlash that would come: “His own particular circle will, I know, take a very different view [of the breakup],” she wrote. “He will be looked upon as a victim, and the general opinion will find it pleasanter to believe that I, in spite of my age, have got rid of him in order to take another lover…” Her predictions about public opinion turned out to be cannily accurate.

It’s also noteworthy that their relationship is often boiled down – wrongly – as one between nurse and caretaker. In his own writings, Liszt, for whatever reason, enjoyed emphasizing Chopin’s weakness and medical troubles, and therefore Sand’s role as his patient helper. However, Sand seemed to chafe against the idea. The relationship was simply more complex than that. She wrote of the Majorca disaster, “It was quite enough for me to handle, going alone to a foreign country with two children…without taking on an additional emotional burden and a medical responsibility.”

Sand and Chopin’s Final Meeting

Both Chopin and Sand left accounts of their final meeting. Comparing them is fascinating.

“I saw him again briefly in March 1848,” Sand wrote in her autobiography. “I clasped his trembling, icy hand. I wanted to talk to him; he vanished. It was my turn to say he no longer loved me.”

Chopin, on the other hand, wrote a longer account in a March 1848 letter to Solange: “Yesterday… I met your Mother in the doorway of the vestibule….” He asked whether Sand had any news about Solange, and let Sand know that Solange had had a baby, since mother and daughter weren’t on good terms at the time. He “bowed and went downstairs.” Then he decided he had more to say, so he asked a servant to bring her to him again. They talked some more. “She asked me how I am; I replied that I am well, and asked the concierge to open the door.”

Chopin died a little more than a year later. Sand opted not to attend his funeral. She lived many more years and wrote many more books.

Despite that tragic end to their love affair – or maybe because of it – George Sand and Frédéric Chopin remain one of the most iconic couples of the Romantic Era.