For one, a symphony can be stylistically of the Romantic Era – Romantic-with-a-capital-R, full of sweeping melodies, warm orchestral colour, and heart-tugging harmonies.

But a symphony can also be romantic in a more personal sense: when it springs from a composer’s love for someone – or even somewhere.

Today, we’re looking at six symphonies that are Romantic in both senses of the word: stylistically of the era, and emotionally rooted in a love story.

All six of these works remain among the most popular romantic symphonies in the classical repertoire.

Berlioz – Symphonie fantastique (1830)

The Love Story

This symphony’s autobiographical program was directly inspired by Berlioz’s own tumultuous love life and romantic fixations.

In 1827, after seeing Irish actress Harriet Smithson perform the role of Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Berlioz became obsessively infatuated with her.

Although the production was in English, Smithson’s performance was so gripping that it electrified Parisian audiences.

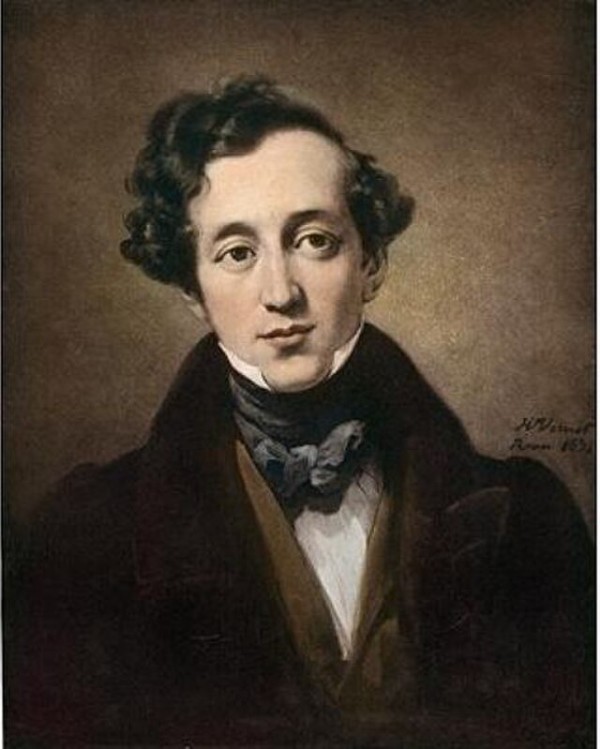

Hector Berlioz in 1832

One audience member in particular was electrified: Hector Berlioz.

He fell in love not with Smithson as a person – he wouldn’t get to know her for quite some time – but rather with her talent and appearance, as well as the many Romantic Era ideals she represented.

While in the throes of this fixation, Berlioz channeled his infatuation into a symphony.

The music is programmatic and, in Berlioz’s own words, follows a “young artist of morbidly sensitive temperament” (a not-so-subtle stand-in for himself) as he plunges from ardent passion into the depths of delusion.

The beloved’s tender theme (idée fixe) is first heard in the symphony’s opening movement, but it later curdles into a vulgar fiddle tune in the witches’ sabbath, symbolising how his idealised love has turned into a nightmare.

The orchestration here is noteworthy, featuring an expanded percussion section, new instruments like the English horn, and striking effects like col legno bowing, where string players tap the wood of their bows on the strings to create spooky sounds.

Harriet Smithson

Berlioz kept trying to get Smithson’s attention. He sent her numerous letters and even went so far as to stalk her lodgings, to no avail. In fact, she didn’t even attend the symphony’s 1830 premiere.

However, two years later, she finally heard a performance. She was astonished that she had inspired such a work, and they soon began dating.

They married in 1833. The marriage collapsed within a matter of years. But this symphony, the spark of inspiration that signaled the start of their relationship, remains a revolutionary Romantic Era statement that out-survived their love – and them.

Mendelssohn – Symphony No. 4, “Italian” (1833)

The Love Story

Horace Vernet: Felix Mendelssohn, 1831

Felix Mendelssohn was not undergoing a tortured love affair while writing the Italian Symphony.

In fact, this work is more influenced by a place he loved than a person: the “romance” here is between the composer and Italy itself.

Mendelssohn’s letters from his 1830–31 Italian journey are ecstatic in their admiration.

“This is Italy! … the supreme joy in life. And I am loving it,” he wrote to his family.

Each movement of the symphony takes on a different aspect of the life he observed in Italy. The joyful first movement is followed by a slow movement reflecting a religious procession he saw in Naples. The dance of the third movement is a standard minuet and trio, and the final movement incorporates two different Italian dances, the quick Roman saltarello (a jumping dance), and the Neapolitan tarantella.

Its joy makes it one of the most “Romantic” – if not overtly romantic – symphonies of the era. Read more about Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4.

Schumann – Symphony No. 1 “Spring” (1841)

The Love Story

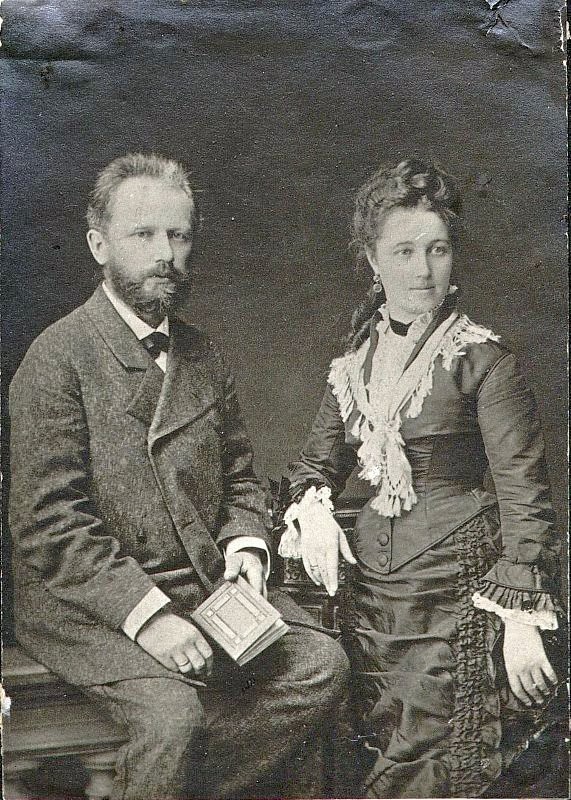

Robert and Clara Schumann

The “Spring” Symphony emerged from the happiest period of Robert Schumann’s life: his first year of marriage to pianist Clara Wieck.

After years of struggling to win the approval of Clara’s father, the star-crossed lovers were finally able to marry in September 1840.

This personal triumph sparked an extraordinary burst of creativity. 1840 had been Robert’s “Year of Song,” when he poured his love into over a hundred love songs.

But by 1841, with Clara’s encouragement, he had turned to the symphony.

She wrote in her diary:

“It would be best if he composed for orchestra; his imagination cannot find sufficient scope on the piano… His compositions are all orchestral in feeling… My highest wish is that he should compose for orchestra – that is his field! May I succeed in bringing him to it!”

As for his part, Robert later said that the work was inspired not just by spring’s external imagery but by his own “spring of love” (“Liebesfrühling”).

Astonishingly, Schumann sketched this symphony out over just four days in January 1841. It exudes all of the exuberance you might expect from such an energetic start.

Schumann wanted the opening trumpet fanfare “to sound as if it came from on high, like a summons to awakening,” heralding spring’s (and love’s) arrival. This motto theme, bold and hopeful, recurs as a unifying idea.

He crafted music that somehow sounds like spring, featuring buoyant rhythms, anticipatory tremolo passages in the strings, and woodwind passages that resemble birdsong.

Throughout, the symphony’s tone is one of youthful hope, excitement, and, importantly, satisfaction. It’s very much in line with Romantic Era ideas and idealism about the rejuvenating power of both love and nature.

Tchaikovsky – Symphony No. 4 (1877)

The Love Story

Tchaikovsky with his wife Antonina Milykova

Few symphonies are as closely tied to a composer’s personal emotional life as Tchaikovsky’s Fourth.

Written in 1877, it coincided with a period of acute turmoil in Tchaikovsky’s romantic and emotional life.

That year, against his better judgment, Tchaikovsky entered into a hasty marriage with a young conservatory student, Antonina Miliukova – a marriage that proved disastrous and lasted only weeks before he fled her forever.

Tchaikovsky may have hoped marriage might quell rumours about his homosexuality, but the reality drove him to a nervous breakdown.

During the aftermath of this catastrophic marriage, Tchaikovsky poured his inner despair and conflict into his fourth symphony.

He described the opening fanfare as the “Fate” that hangs over a person’s life: a concept that colored the entire symphony.

In a candid letter to his patroness and confidante, Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky admitted: “I was very depressed last winter when writing the symphony, and it is a faithful echo of what I was experiencing.”

Madame von Meck, who became Tchaikovsky’s benefactor in 1877, actually played a critical role in the symphony’s creation and the composer’s life at that particular time.

She provided financial support so he could quit teaching, along with an emotionally intimate – if strictly epistolary – friendship.

Nadezhda von Meck

The dedication of the fourth symphony even reads “To my best friend”: Tchaikovsky’s tribute to von Meck, and a thank-you for helping to usher him through an especially trying time in his life.

It’s ironic that one of the most infamous marital breakdowns in classical music history inspired one of the standout symphonies of the Romantic Era.

Mahler – Symphony No. 5 (1901–02)

The Love Story

Alma Schindler, 1902

The years 1901–1902, when Mahler composed his Fifth Symphony, were momentous in his personal life, especially in terms of romantic love.

In November 1901, Gustav Mahler met Alma Schindler, a young composer and socialite from Vienna.

Their whirlwind courtship was intense; by March 1902, they were married. (Alma was pregnant at their wedding.)

This intense new love had a profound impact on Mahler, and we see its reflection most clearly in the symphony’s Adagietto.

According to Alma’s testimony, the Fifth’s Adagietto (which starts at the 46:15 mark in the video above) was Mahler’s love song to her.

Historians have noted that Alma’s picturesque storytelling isn’t always strictly accurate, but the following story remains persuasive. Apparently, he left her a small poem with the Adagietto’s manuscript, saying: “How much I love you, my sun, I cannot tell you in words – only my longing and my love and my bliss.”

Today, the Adagietto is regarded as the wordless love letter from Mahler to his new wife, communicating in music what he felt he was unable to say in words.

It provides a transcendent counterbalance to the earthiness of the rest of the symphony, enhanced by its orchestration for strings and harp alone.

Rachmaninoff – Symphony No. 2 (1907)

The Love Story

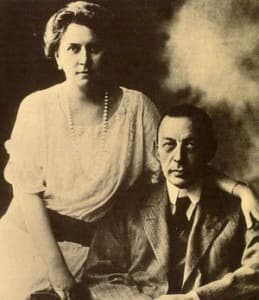

Sergei Rachmaninoff and Natalia Satina

The creation of his Symphony No. 2 marked a particularly redemptive chapter in Rachmaninoff’s professional life: one shaped by the support and love he found in his marriage.

A decade earlier, in 1897, Rachmaninoff’s first symphony had premiered to disastrous reviews (one critic likened it to “a program symphony about the Ten Plagues of Egypt”).

The fiasco of that premiere sent the young composer into a deep depression and a creative block. He recovered only with the help of therapy and through composing his successful Second Piano Concerto (1901).

During that same period, he fell in love with and became engaged to Natalia Satina, his cousin and childhood sweetheart.

After overcoming significant obstacles (including family disapproval and Orthodox Church restrictions on cousin marriage), Sergei and Natalia married in 1902 on a rainy spring day.

By the time he was writing the second symphony in 1906, Rachmaninoff had been happily married for a few years and was a father. His first daughter, Irina, was born in 1903, and his second, Tatiana, was born in 1907.

Enjoying such a stable, loving home life provided Rachmaninoff with a foundation of emotional security that was crucial to his productivity after the turmoil of his earlier years.

In late 1906, he and Natalia moved to Dresden specifically to escape the pressures of Moscow so that he could focus on composition in peace.

There, with his wife and daughter by his side, he worked on the symphony – though not without bouts of self-doubt.

At one point, he nearly abandoned the score, calling it “boring and repulsive” in a typical burst of self-criticism, before eventually returning to it.

It’s easy to imagine that the heartfelt outpouring of the symphony – especially its incandescent Adagio – was nurtured by the contentment and warmth of Rachmaninoff’s married life.

The triumphant premiere of the symphony in early 1908 in St. Petersburg was a vindication; the public and critics hailed it, and it earned Rachmaninoff a prestigious Glinka Award.

Today it remains one of the symphonic highlights of the late Romantic Era, beloved for its lush string writing and deeply felt, warmly expressed emotion.

Conclusion

Romanticism in symphonic music wasn’t just an artistic movement; it was also a way for composers to transform their private longing, devotion, and emotional crisis into publicly performed art.

From Berlioz’s hallucinatory passion in the Symphonie fantastique to Rachmaninoff’s newfound confidence in his Second, these six works reveal how love – fulfilled, frustrated, or otherwise – shaped some of the most powerful music of the Romantic Era.

Taken together, they show just how deeply composers’ love stories shaped their compositions, and why these pieces remain so easy to love even today.

No comments:

Post a Comment