It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, May 30, 2025

The Alan Parsons Symphonic Project "Sirius" - "Eye In The Sky" (Live)

An Introspective Journey: Vanessa Wagner’s Miniatures

by Maureen Buja

The idea of the piano miniature has largely faded from the scene, but in the 19th century, particularly fuelled by the rise in home ownership of pianos, composers by the score wrote little consequential pieces for their audience.

Vanessa Wagner

French pianist Vanessa Wagner (b. 1973) has taken piano miniatures by four different composers and used them to weave a world of the imagination.

Wagner opens with Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, Op. 37a, written for a monthly musical magazine based in St Petersburg, Nouvellist. The editor, Nikolay Matveyevich Bernard, commissioned Tchaikovsky for 12 character pieces, one for each month. Bernard gave Tchaikovsky the titles and all through 1876, the pieces appeared. In January we are by the fireside, in May are the White Nights, and we’re riding in a troika in November.

Nikolai Dmitrievich Kuznetsov: Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1893

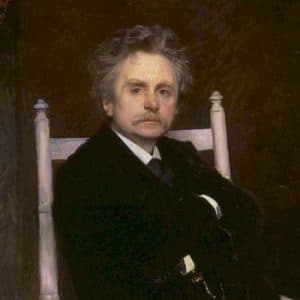

Next follows selections from Edvard Grieg’s Lyric Pieces. This collection of 66 short pieces for piano was published in 10 volumes from 1867 to 1901. She chooses two of the best-known pieces, Wedding Day at Troldhaugen and Butterfly, and supplements them with Little Bird and other works, closing her Grieg section with Grandmother’s Minuet.

Hjalmer Peterssen: Edvard Grieg, 1891

Selections from the rarely heard Six Impromptus, op. 5, by Jean Sibelius, bring us a side of Sibelius we aren’t as familiar with. Sibelius’ orchestral works are what made him famous, but Wagner finds these little piano pieces to be ‘absolutely sublime’.

Daniel Nyblin: Jean Sibelius, ca 1898–1900

Yakov Yanenko: Mikhail Glinka, 1840

The recording closes with Glinka’s nocturne entitled La Séparation. Just as little known as the Sibelius Impromptus, the Glinka work brings an end to Wagner’s fantasy narrative. She says, ‘It depicts the loneliness that can result from the quest for an unattainable, fantasy love, …and is a favourite theme of Romanticism. Glinka’s piece seemed to me to be the end of the story I had imagined for myself. It was a gentle, sensuous conclusion to a journey tinged with tenderness, sadness and hope, like the cycle of the seasons’. She ties Glinka’s melancholic work back to the opening piece by Tchaikovsky and makes it a fitting end.

One writer comments on the collection that ‘she follows the paths less travelled and takes us to places where we might not have expected her to go’. By connecting these works, she takes us from the miniature worlds of Tchaikovsky and Grieg, which were very much influenced by the Songs Without Words by Mendelssohn, and takes us into the more introspective works by Sibelius and Glinka. It’s a lovely journey and is a recording that, in addition to impressing you with its skill, leaves you at the end in a pensive mood, reflecting on the journey taken and the one that now lies ahead.

Everlasting Seasons: Tchaikovsky, Grieg, Sibelius, Glinka

La Dolce Volta: LDV 126

Release Date: 4 October 2024

Official Website

Ten of the Best Nocturnes by Women Composers

by Emily E. Hogstad

The most famous were written by canonical composers like John Field, Chopin, and Debussy.

However, many women composers outside the traditional canon have also crafted stunning nocturnes, and they deserve to be listened to, too.

Today, we’re looking at nocturnes by ten women composers written between the 1820s and the 1920s.

Maria Szymanowska (1789 – 1831)

Nocturne in B-flat Major (ca. 1825)

Maria Szymanowska was born Maria Wołowska in Warsaw, Poland, in 1789.

Maria Szymanowska

We don’t know much about her early years, but we do know that she studied with Józef Elsner, who taught Chopin. In fact, her work has often been compared to Chopin’s, although she was born twenty years before him.

She made her Warsaw and Paris debuts in 1810, with her career really taking off in the late 1810s and 1820s.

Tragically, she died during a cholera epidemic in St. Petersburg in 1831.

Szymanowska wrote around a hundred works for piano. Her best-known is her Nocturne in B-flat Major, which Szymanowska scholar Sławomir Dobrzański calls “her most mature piano composition.”

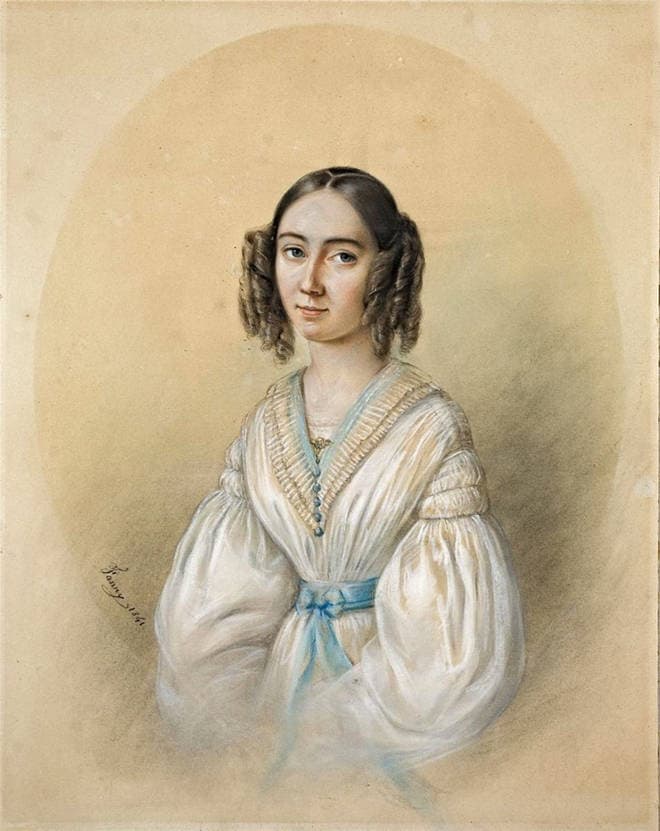

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805 – 1847)

Fanny Mendelssohn was born in 1805, four years before her famous brother Felix. Just like him, she was a jaw-droppingly talented musical prodigy. By fourteen, she could play all twenty-four of the preludes from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier.

Fanny Mendelssohn

However, unlike her brother, she was not permitted to become a professional musician due to her gender and elevated social station. A family friend once wrote:

Had she been a poor man’s daughter, she must have become known to the world by the side of Madame Schumann and Madame Pleyel as a female pianist of the highest class.

This didn’t keep her from composing, even if she was discouraged from publishing. She wrote over 450 pieces of music.

Shortly before her death, she decided she wanted to start publishing her works, but due to her early death, it would fall to later generations to promote her music.

Fanny wrote her G-minor nocturne in 1838 in the style of a Venetian boat song.

Clara Wieck Schumann (1819 – 1896)

Clara Wieck was born in September 1819 to piano teacher Friedrich Wieck and his wife, singer Mariane.

Friedrich wanted to turn Clara into a piano virtuoso who could serve as an advertisement for him and his methods. Consequently, Clara was forced to practice for hours every day as a child.

Clara Wieck at 16 years old

She made her debut at the Gewandhaus concert hall in Leipzig at the age of nine, and when she was twelve, she and her father began touring across Europe.

In addition to performing, she also composed, just like the other great male pianists of her generation. In 1836, the year she turned seventeen, she wrote this stunning nocturne.

The day before her 21st birthday, Clara Wieck defied her father’s wishes and married composer Robert Schumann.

Louise Farrenc (1804 – 1875)

Louise Farrenc was born Jeanne-Louise Dumont into a family of Parisian sculptors in 1804.

From an early age, it was clear that she was musically talented. However, she couldn’t enroll at the Paris Conservatoire because women instrumentalists and composers weren’t allowed to study formally there.

Louise Farrenc

Instead, she studied with composition professor Anton Reicha independently. (Reicha was a friend of Beethoven‘s, who also taught Berlioz and Liszt.)

In 1821, she married music publisher Aristide Farrenc. Many women of her generation retired when they married, but Farrenc did not; she continued her professional life working as a pianist, teacher, and composer.

Her fame continued to grow and, in a full-circle moment, in 1842 she was named as a professor at the Paris Conservatoire. After the successful premiere of her Nonet for string quartet and wind quintet at the Conservatoire, she demanded – and finally received – equal pay to her male colleagues.

She died in Paris in 1875.

Mélanie Chasselon (1845 – 1923)

Like many women composers in the history of music, we don’t know much about Mélanie Chasselon (yet!).

She was born in 1845 in Ligny-en-Barrois in northeast France. She was the organist and choirmaster at a church in her hometown. Beyond that, we know very little about her biography.

Her music was published by the Heugel music publishing company, based in Paris.

Hopefully in time, music historians will uncover more about her life and other works, because this nocturne is wistfully beautiful.

Rebecca Clarke (1886 – 1979)

Rebecca Clarke was born just outside of London in 1886. She became interested in music after her brother started taking violin lessons from their father.

Rebecca Clarke

She studied at the Royal Academy of Music in 1903, dropped out briefly after a professor proposed to her, then enrolled in the Royal College of Music.

She ended up becoming a professional orchestral violist to support herself. She also composed. This ethereal nocturne for two violins and piano dates from this early part of her career.

Lili Boulanger (1893 – 1918)

Lili Boulanger was an extraordinary child prodigy. She started going to classes at the Paris Conservatoire with her older sister Nadia when she was only five years old.

Lili Boulanger

Unfortunately, her health was very poor. In 1912, she competed in the prestigious Prix de Rome competition, but had to drop out because she became too sick to continue.

She tried again in 1913. Her persistence paid off: her cantata Faust et Hélène won the competition, making her the first woman to win the Prix de Rome. Read more from “The Sisters of the Prix de Rome – Nadia and Lili Boulanger”.

Her health deteriorated during World War I. She died of intestinal tuberculosis in 1918 at the age of twenty-four.

Her devastating early death marks one of the most painful what-ifs in classical music history.

Dora Pejačević (1885 – 1923)

Dora Pejačević was born to a noble family in Budapest in 1885, with a Croatian father and a Hungarian mother.

She was well-educated, well-read, and famously independent, holding strong opinions about a wide variety of social, political, and economic issues.

Dora Pejačević

She once wrote in a letter:

It’s true that I don’t align with members of my social class; in everything, I seek substance and value, and neither norms nor traditions nor lineage can blind me with sand in my eyes…

Pejačević began composing at the age of twelve, but because of her gender and social station, she never took regular lessons from a professional teacher and was mostly self-taught.

She worked as a medic in World War I, and wrote these two nocturnes toward the end of the war.

Pejačević died a few years later in 1923, shortly after giving birth to a son.

Amy Beach (1867 – 1944)

Amy Beach was the first famous American composer. She was born Amy Cheney in 1867 in New Hampshire and became an astonishing child prodigy, beginning to compose at the age of just four.

Like several other women on this list, because of her gender and social station, she wasn’t permitted to study composition formally. However, she did take private lessons with tutors out of Boston, and she spent countless hours teaching herself out of textbooks.

Amy Beach

In 1885, when she was eighteen, she married a doctor named Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach, who was over twice her age. Despite the age difference, she wrote later in life that their marriage was a happy one.

At the time, it would have been embarrassing for such a well-established older man to have a wife who made a living by appearing on the stage, so she focused on composition instead.

In 1896, the Boston Symphony performed her Gaelic Symphony, which was the first symphony by a woman performed by a major American orchestra.

Her husband died in 1910, and she never remarried. Instead, she embraced her career as a composer and piano soloist.

This nocturne dates from the later part of her career. It is written in a traditional romantic idiom, but also experiments with more modern, complicated harmonies.

Cécile Chaminade (1857 – 1944)

Cécile Chaminade was born just outside Paris in 1857.

At the age of ten, it was recommended that she attend the Paris Conservatoire. However, like so many of the other women on this list, she studied music privately instead.

Cécile Chaminade

She eventually became famous for writing charming salon pieces and chamber music, and these works were hugely popular and financially successful. In fact, Chaminade Clubs were formed all around the world!

Twentieth-century critics have dismissed her works and salon pieces generally, in no small part because of sexism, but there’s no denying that this gently charming nocturne is worth listening to and loving.

Niccolò Paganini’s Devilish Genius>: 10 Tracks that Conjure his Violin Sorcery

by Hermione Lai

In the 19th-century concert hall, Niccolò Paganini emerged like a figure plucked from a dark fairy tale. His tall, gaunt frame was cloaked in black, with his long jet-black hair trailing like a shadow.

Niccolò Paganini

He moved with quiet intensity, and when he raised his violin, it was not just an instrument but a magical wand ready to cast a spell. Audiences didn’t just listen but were transfixed, caught in his nimble dance across the strings that felt almost unnatural.

Offstage, Paganini was a mess, gambling away fortunes, chasing romance, and living on borrowed time. However, when he played, none of that mattered. He didn’t just perform but summoned something primal that could make you feel the weight of a broken heart or the thrill of a midnight chase.

Paganini died at the age of 57, on 27 May 1840. And what better way to commemorate his passing than to feature 10 tracks that conjured his violin sorcery.

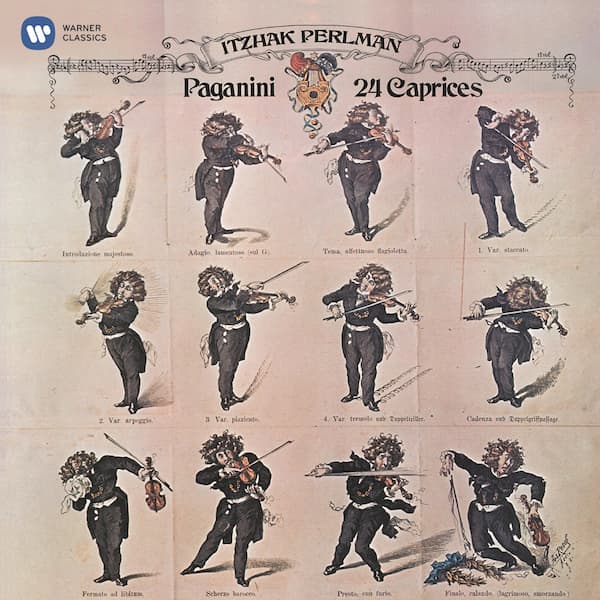

Caprice No. 24 in A minor, Op. 1

Niccolò Paganini’s Caprices

The Caprice No. 24 in A minor is the crown jewel of Paganini’s Op. 1 set of 24 Caprices. This collection of solo violin works redefined what the instrument could do. Known for its ferocious technical demands and electrifying energy, this piece has captivated listeners and terrified violinists for nearly two centuries.

This dark and driving theme, followed by dazzling variations, has inspired countless musicians, from classical composers to modern rock guitarists. The piece starts with a punchy theme that sounds like a musical hook, instantly grabbing attention.

The rhythm is bold and a little menacing, and the catchy melody builds on a driving pulse. But that’s just the opening, as the piece unfolds through 11 variations, each one a mini-adventure that showcases a different technique or mood.

“La Campanella” (The little Bell) comes from the third movement of Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in B minor, Op. 7. It is without doubt one of his most beloved and dazzling works, and it has been adapted for any and all instruments imaginable.

Known for its shimmering, bell-like melody and jaw-dropping virtuosity, this piece captures the magic of Paganini’s “Devilish Fiddler” reputation in a way that’s both enchanting and fiendishly challenging.

Written in 1826, it is a perfect blend of lyrical charm and technical wizardry. The light and playful opening melody in the upper register mimics the chime of a little bell, while the episodes sound like virtuosic fireworks. The combo of delicate harmonics, breakneck speed, and intricate bow work makes this a nightmare for even the most seasoned violinist.

Caprice No. 13 in B-flat Major, Op. 1 “Devil’s Laughter”

Niccolo Paganini shown spellbinding a young English lady with his music, in an etching from 1900 © Bettmann Archive/Bettmann

The Caprice No. 13 from the legendary 24 Caprices set is a dazzling solo violin piece that pulses with mischievous energy. Nicknamed “The Devil’s Laughter” for its playful yet slightly sinister trills, this work blends technical brilliance with an almost supernatural vibe.

The piece starts with a series of rapid, high-pitched trills, short, vibrating notes that sound like a chuckle or a shiver. It feels like the violin is giggling, hence the catchy nickname.

The trills, which dominate the piece, sound effortless in the hands of a master but are brutally difficult to play at speed. The sudden shift to the darker middle section adds a touch of menace, and when we combine it with Paganini’s almost supernatural stage presence, it’s no wonder that the audience thought he was possessed.

Cantabile in D Major, Op. 17

The Paganini Cantabile in D Major, Op. 17, is a breathtaking departure from his usual fiery and virtuosic showpieces. Composed around 1824, this short lyrical work for violin and piano—sometimes guitar—reveals the composer’s tender and soulful side.

With its singing melody and delicate charm, the Cantabile feels like a love letter set to music, proving that Paganini could melt hearts as easily as he dazzled crowds.

The magic of the Cantabile lies in its emotional depth. The challenge isn’t speed but sensitivity, making the violin sing with warmth and clarity without overdoing the vibrato. Its simplicity is deceptive, as it requires a master to bring out its full beauty, with Paganini crafting a timeless melody.

Caprice No. 9 in E Major “The Hunt”

The Caprice No. 9 in E Major is a vibrant and thrilling solo violin piece nicknamed “The Hunt.” What a wonderful evocation of a hunting scene, full of galloping rhythms and horn-like calls.

The work captures the excitement of a chase through the wilderness, all while showcasing Paganini’s trademark virtuosity. Composed in the early 1800s, it is one of the more picturesque caprices, blending technical dazzle with a playful and almost cinematic energy.

This Caprice isn’t overtly menacing, but its devilish quality comes from its relentless pace and technical demands. The double stops in the horn-call sections require strength and accuracy, while the rapid runs test speed and dexterity. The playful yet driving energy, hinting of a wild chase, adds to the sense of something seriously untamed.

The Arpeggio

The opening piece of his legendary 24 Caprices is an electrifying solo violin work nicknamed “The Arpeggio” for its whirlwind of sweeping, chord-like passages. Bursting with energy and technical bravado, it’s like a musical lightning bolt that gets the set started.

This caprice earned its devilish reputation through its sheer technical ferocity. Just listen to the ricochet bowing as the arpeggios demand lightning-fast finger work across all strings.

Once you add in the wide leaps, dynamic shifts, and unrelenting pace, it’s a recipe for a nightmare. When Paganini performed it with apparent ease and added his almost supernatural stage presence, everybody wondered how a human could possibly play like this. The music, this mix of brilliance and chaos, feels like a force of nature.

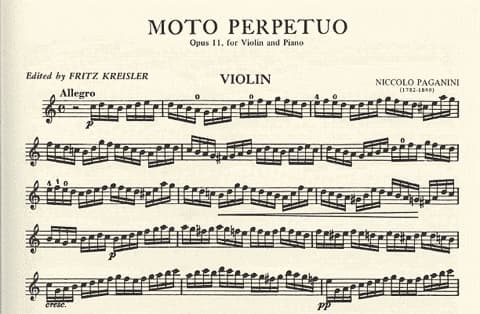

Moto Perpetuo in C Major, Op. 11

Niccolò Paganini’s Moto Perpetuo

The breathtaking solo violin piece “Moto Perpetuo” is a high-energy work that sounds like a nonstop cascade of rapid notes that push the violin and its player to the absolute limit. This piece is all about relentless speed and endurance.

The “Moto Perpetuo” comes from the later stages of Paganini’s career, reflecting his love for dazzling audiences with sheer virtuosity. It’s not a very complex piece, but the violin becomes a vehicle for raw and exhilarating power.

After nearly five minutes of nonstop playing, the piece concludes with a brief and emphatic flourish. The quick chord feels like slamming the brakes after a seriously wild ride. Today, it is often used in recitals or competitions to demonstrate a player’s stamina and control. Once again, Paganini turned the violin into a force of nature.

Caprice No. 5 in A minor

Niccolò Paganini’s Caprice No. 5

One of the most thrilling and intimidating pieces in the set, the Caprice No. 5 is known for its breakneck speed and fiendish technical demands. It showcases Paganini’s ability to push the violin to its limits while conjuring a dark and electrifying energy.

The piece is short but rather intense. In three main sections, Paganini creates a sense of relentless motion dominated by rapid arpeggios and scales. A successful performance demands superhuman speed, stamina, and precision.

The Caprice No. 5 is a recital and competition staple, and its reputation as one of the toughest pieces in the set makes it a badge of honour for players. For performers, it is a gruelling test of skill and endurance demanding total focus; for listeners, it’s a pulse-pounding ride that never lets go.

Caprice No. 17 in E-flat Major

Sparkling with charm and technical brilliance, the Caprice No. 17 is known for its lively, dance-like energy and intricate interplay of contrasting themes. It feels like a musical conversation, playful yet seriously demanding.

Once again, Paganini showcases his ability to blend accessibility with jaw-dropping virtuosity, making it one of the more approachable yet still dazzling pieces from the set.

This caprice alternates between a lyrical theme and virtuosic passages, creating a back and forth between two different personalities. One is calm and melodic, the other fiery and acrobatic. Yet it all flows naturally, but the switch between these contrasting moods is a test of versatility and stamina.

Violin Concerto No 1 in D Major, Op. 6 “Allegro Maestoso”

Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 1 is a thrilling masterpiece that captures the essence of his legendary status as the “Devil’s Fiddler.” It is a work of tour de force, lyrical melodies, breathtaking technical feats, and dramatic flair.

Composed around 1817/18, this concerto weaves the violin’s brilliance into a rich orchestral tapestry, creating a grand theatrical experience. It’s a devilish blend of ferocity and charismatic showmanship, and the first movement is packed with horrendous challenges: rapid runs, wide leaps, double stops, and harmonics.

The cadenza is a high-stakes moment to flaunt every trick in the book, and the opera-like drama of soaring melodies and explosive virtuosity feels like a theatrical spell. Paganini’s music is a blend of devilish complexity and captivating beauty, and it continues to challenge violinists and enchant listeners. His legacy remains a vibrant force in music today.