Leipzig Connection

Edvard Grieg, 1858

As Grieg famously stated, my songs are “written with my life-blood.” His early music clearly reflects his studies in Leipzig, and he only discovered folk music in the mid-1860s. Taking his inspiration from two pioneers of Norwegian folk music, “Grieg was the chosen one, who wooed the princess from the mountain and won half the kingdom.”

Grieg did acknowledge Schumann as his mentor, as the “Poetic conception plays the leading part to such an extent that musical considerations are technically important are subordinated, if not entirely neglected.” Grieg’s ability to write songs is attributed to the influence of his wife Nina, and when they had relationship tensions, he composed no songs at all.

Songs from the Heart

As he wrote to a friend, “I do believe I have more talent for song composition than for any other genre in music. From when does it come then, that the song plays such a prominent role in my output? Quite simply for the reason that I, like other mortals, on one occasion in my life, was brilliant.”

And Grieg continues, “The brilliance was love. I fell in love with a young girl with a wonderful voice and similarly wonderful interpretation. This girl became my wife and life’s partner right to this day. She has been, for me, the only true interpreter of my songs.”

Grieg and Poetry

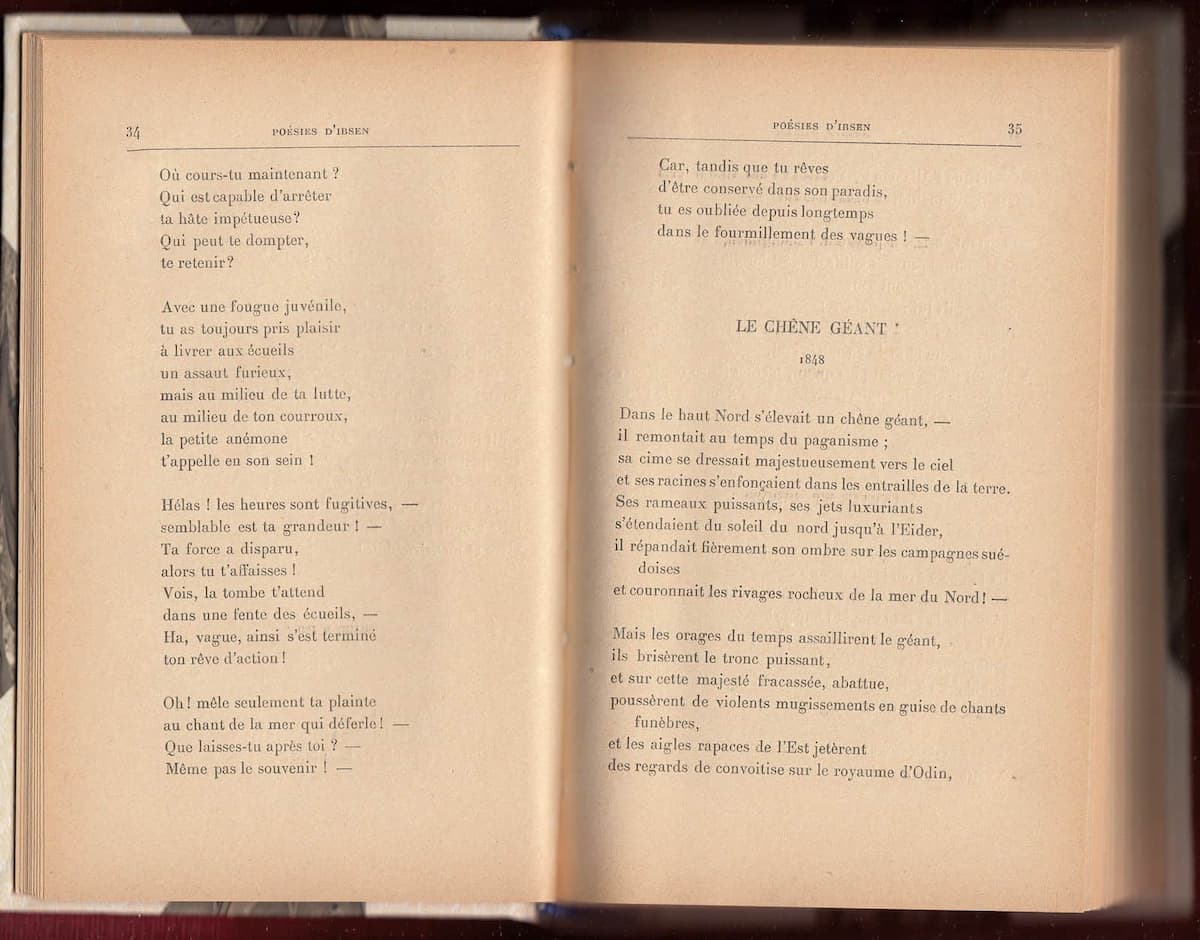

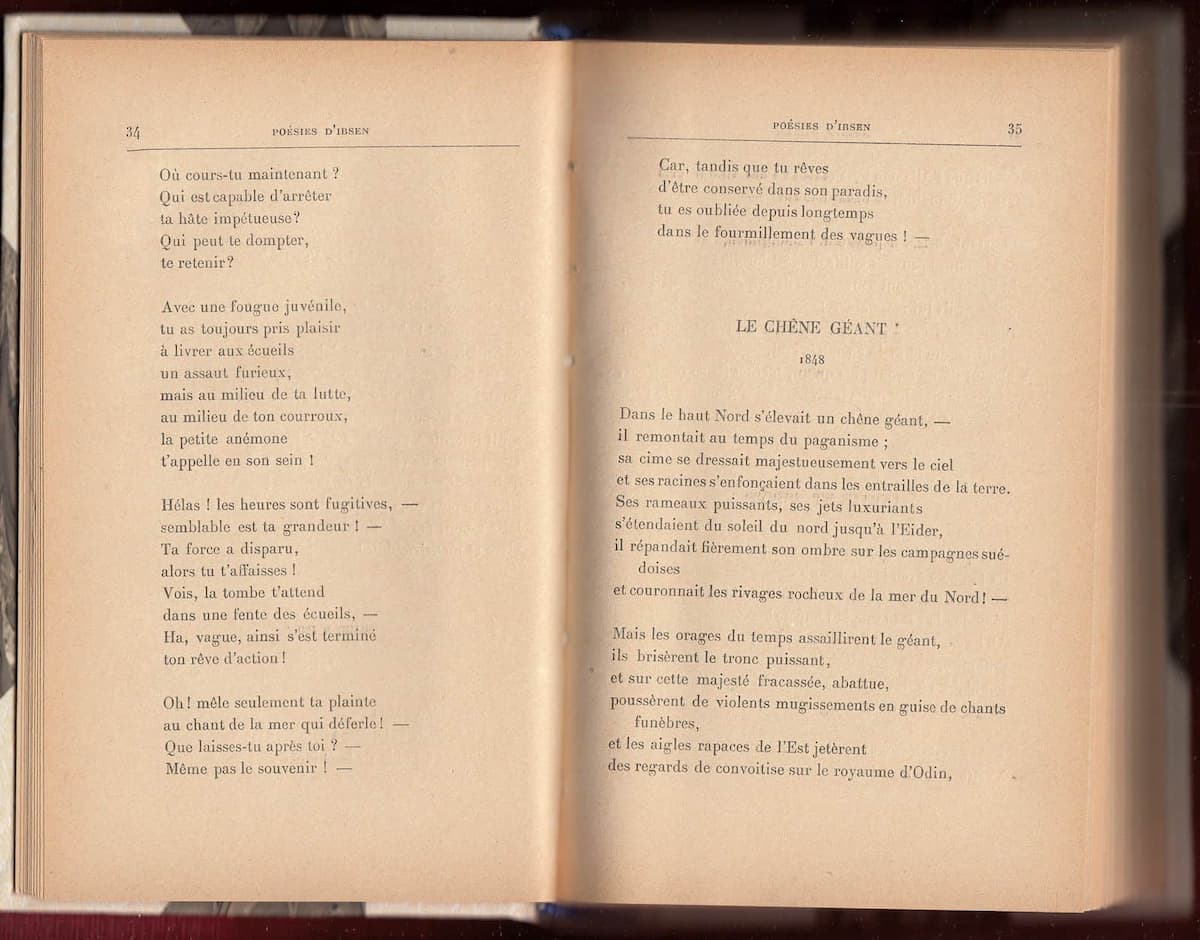

1907 Poésies by Henrik Ibsen

Grieg was very receptive to all kinds of poetry, even when, on occasions, he selected rather inferior verse. He always composed music to suit the intrinsic melody of the words, whatever the language. A scholar writes, “there is something in the Scandinavian psyche which appears to regard being happy as tempting fate, so a darker feeling is often to be detected behind the seemingly innocuous.”

Writing to a friend, Grieg explains, “For me, it is important when I compose songs, not first and foremost to make music, but above all to give expression to the poet’s innermost intentions. To let the poem reveal itself and to intensify it was my task. If this task is tackled, then the music is also successful. Not otherwise, no matter how celestially beautiful it may be.”

Grieg and Ibsen

Ibsen had been impressed by Grieg’s musical talents from their first meetings in Rome in 1866 and also by the young composer’s perception of literature. The collaboration on Peer Gynt turned out to be a major headache for Grieg, both in terms of composition and eventual performance. Yet, as we know, it became a qualified success.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Grieg turned to Ibsen’s poetry for possible song texts. Grieg explained that the “truth wrapped up in rhyme is easier to accept than it is in prose, and it seems that Ibsen was more able to give direct expression to his thoughts in verse than in prose.”

Ibsen Poetry

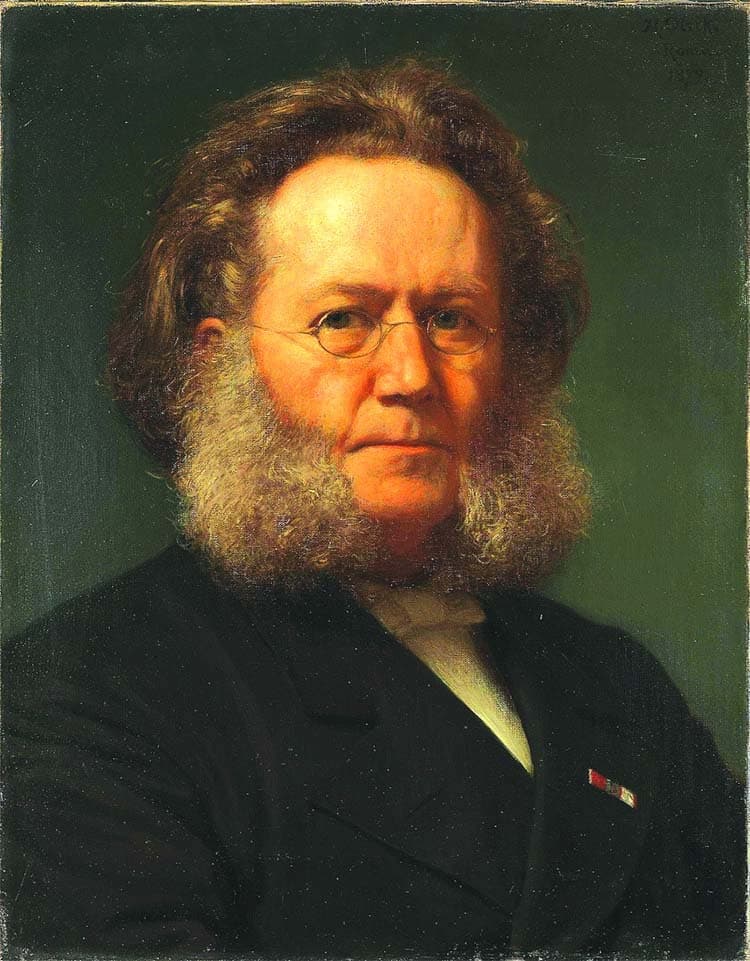

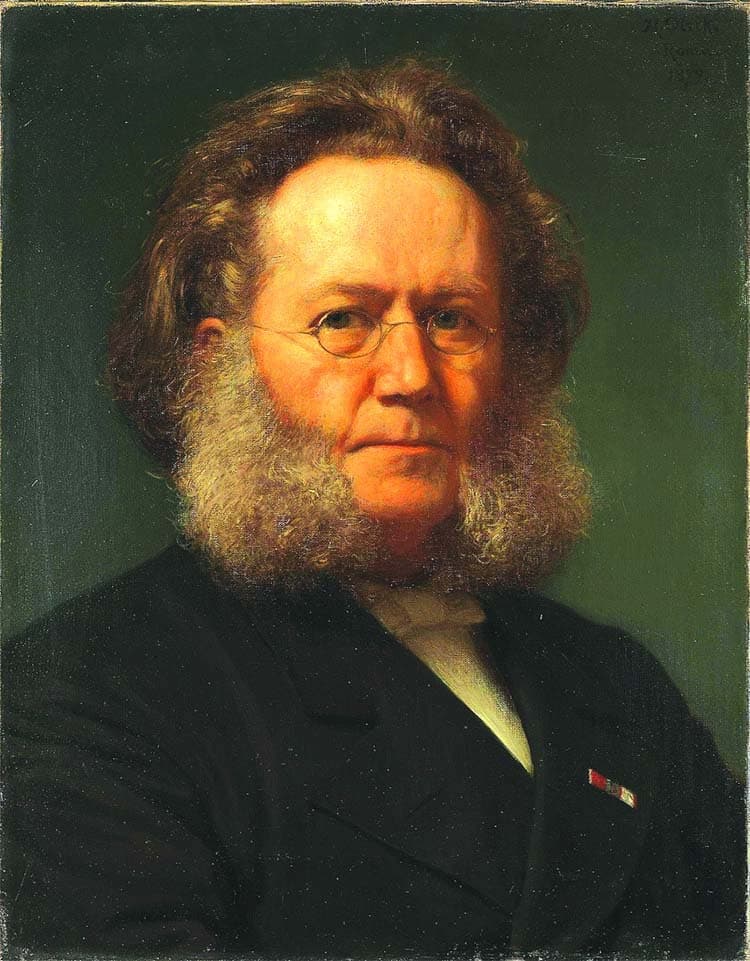

Henrik Ibsen

Ibsen’s poetry, much revised prior to publication, shows a wide diversity of styles. It ranges from purely elegiac to imagery and expression, songs in verse form, plays, and narrative poetry. And let’s not forget the occasional political verse, such as the poem on Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

Almost all of Ibsen’s poetry is marked by concentration of content. “He most often uses nouns and verbs with few accompanying adjectives or adverbs. He makes use of contrast and antitheses, and the concentration is not just of ideas, frequently taken to their limits throughout a poem, but it is also to be found in the imagery and vocabulary he chooses.

6 Poems by Ibsen, Op. 25

In 1876, Grieg found Ibsen’s fateful poetry a match for his own state of mind. He had lost both his parents within a short period of time, “each strangely dying a day before an advertised concert, which then had to be cancelled.” In addition, his marriage was going through a rather unsettled period, and Grieg poured his anguish into his music.

This prevailing mood of despair drove Grieg to Ibsen’s verse, and the six poems set in his Op. 25 convey his melancholy in a most inspired way. “The understated rife in the poetry, the restraint of the emotion and the concentration of ideas are all mirrored in the music.”

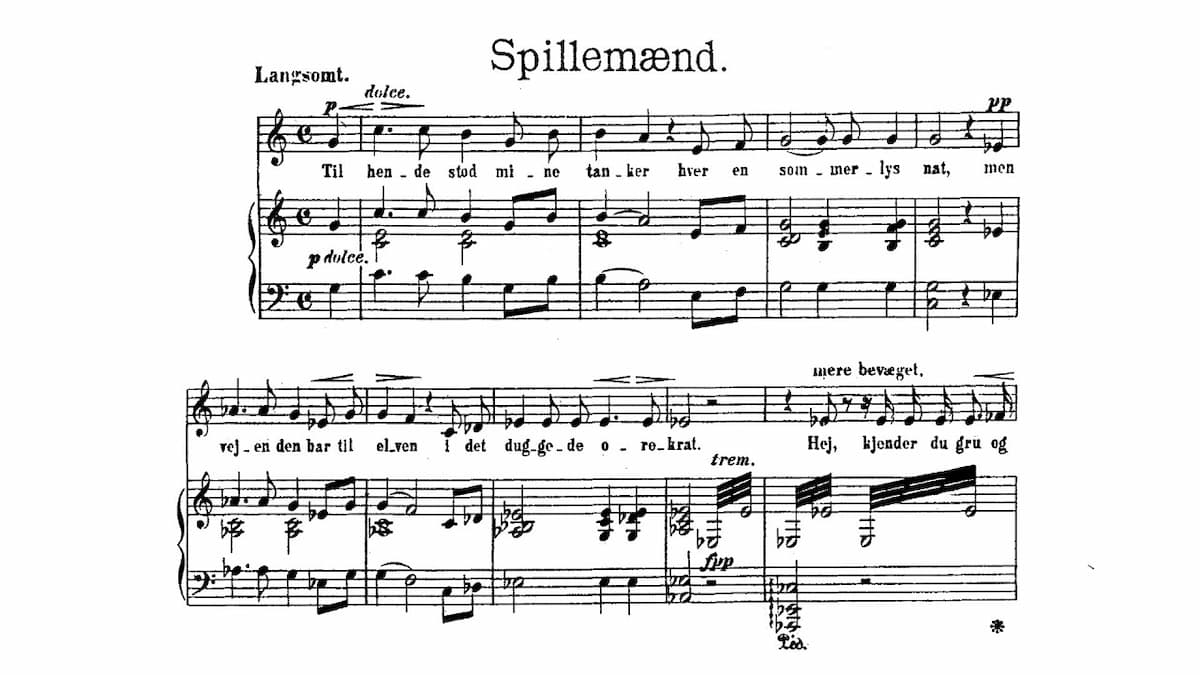

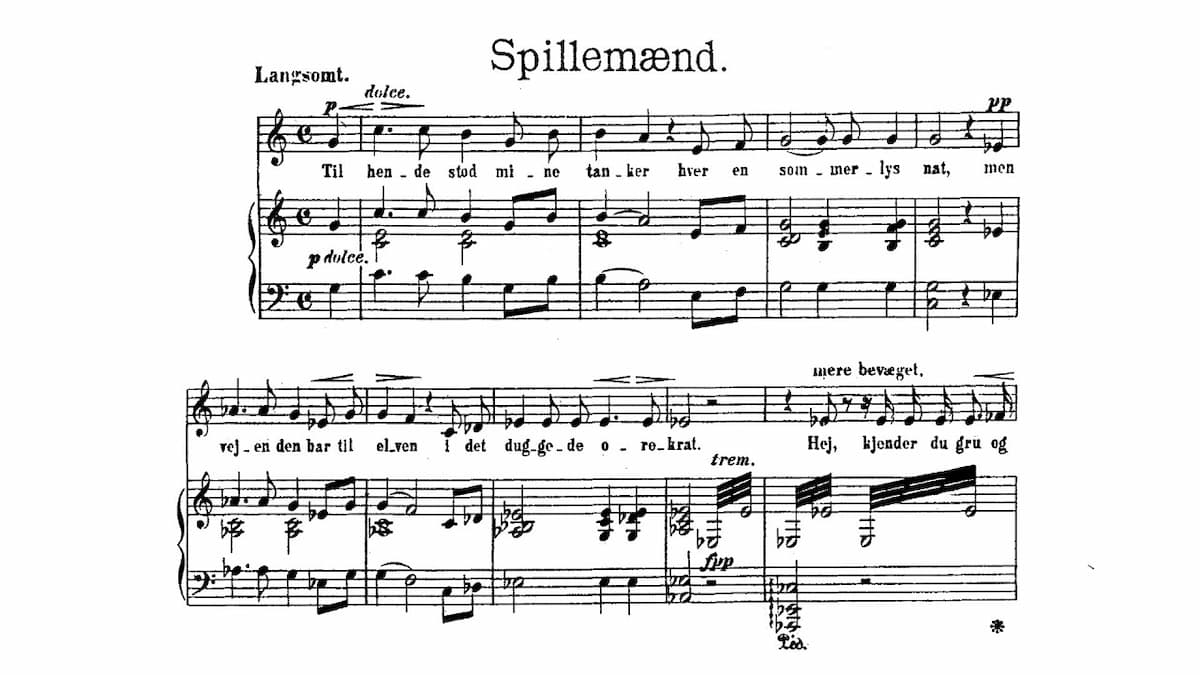

My thoughts were of her

Every light summer night,

But the road leads to the river

By the dewy alder.

Do you feel a shudder and anguish,

Can you bewitch her lovely senses,

So that into great churches and halls

She will be minded to enter with you.

I commend forth the spirit from the deep;

He led me away from God,

But when I became his master

She became my brother’s bride.

Into great churches and halls

I played myself

And the shuddering and anguish of the falls

Was never far from my mind.

“Minstrels” is based on a familiar Norwegian legend of a musician who is taught great powers of interpretation by a water sprite, only to find himself having to repay the debt with his own happiness. A literary critic wrote, “the poem presents a view of Ibsen as a haunted man, who is always seeking to break through to the light, is often beset by the doubt whether darkness might not, after all, be the natural abode of men.”

Grieg’s setting has been described as one of his finest achievements. There is great vocal simplicity in the opening measures supported by a straightforward accompaniment. As the song modulates, we learn about the minstrel being lured to the river. The central part features recitative-like declamation, with chromatic movements in the inner part of the piano mirroring the development of the story. The Minstrel finally accepts his fate but the unsettled nature of the song also hints at rumours “that Nina Grieg was having an affair with Edvards’ brother John.”

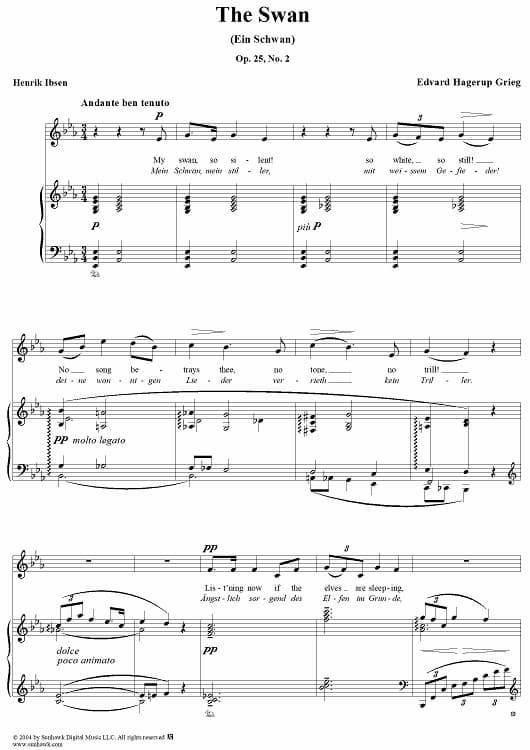

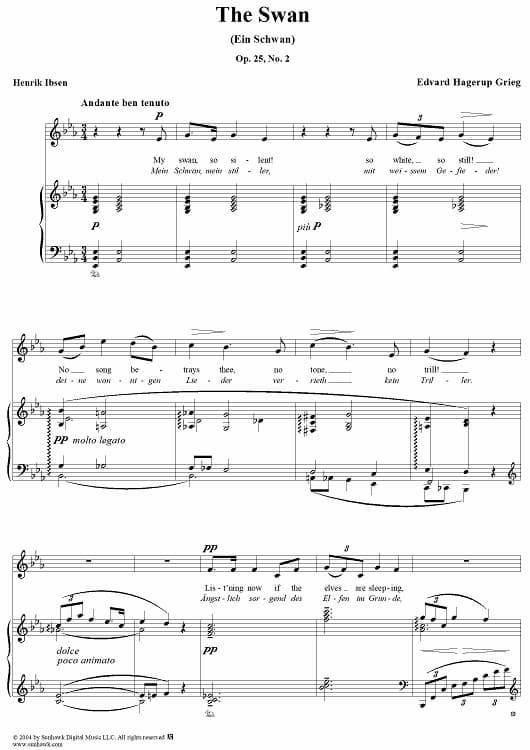

Edvard Grieg’s 6 Poems by Henrik Ibsen, Op. 25 “The Swan”

My white swan

Silent and still,

Neither form nor drill

Gives promise of your voice.

Anxiously protecting

The sprite who sleeps,

Every listening

You glided past.

But the last meeting

When oaths and promises

Were but lies

Then, then it was heard.

In the birth of those tones

You ended your path.

You sang in death;

For you were a swan.

In Norse mythology and literature, and in Celtic writing, the motif of swans linked by a silver chain is “the symbol of divine beings in metamorphosis.” For Ibsen, the swan was a symbol of the soul and “typifies the Norse belief in the dark unknown passions and haunting obsessions above which life must be raised and against which it must be defended.”

The Grieg setting is marked “slowly and restrained,” and there is a great atmosphere of stillness. Grieg presents a very basic harmonic structure, but the accompaniment chords have altered chromatic notes, describing the swan movement. Grieg shows a natural restraint, which he powerfully casts aside in the fortissimo climax. Grieg once conducted the orchestrated version of the song with the Belgian singer Grimaud, “performing wonderfully well with great dramatic accent.” Grieg commented that “No Norwegian would have dared to give such an interpretation because our nature would have to struggle with our national shyness.

I called you my bearer of good tidings;

I called you my star.

You were sent from God.

Good tidings went forth;

A star, a cascade of stars,

That died in the distance.

“Album Verse” is one of the most concise poetic and musical settings. In fact, as it is only twelve measures long, it is Grieg’s shortest art song. Despite this brevity, Grieg still manages to construct a lyrical piece in ABA form. This brevity somehow vails the meaning, as the reader is only aware that a beloved messenger of joy, is no more.

Grieg musically matched this utter despair with a sighing and broken melody in the minor key, with syncopated chords in the right-hand accompaniment. Grieg is once more primarily concerned with declamation and not with the beauty of the vocal line. As the verse has a rather elusive quality, seemingly an episode without a beginning or end, the unexpected lyricism in the left-hand accompaniment does come as a surprise.

Lock, Marie, what I bring

The flower with its white wings.

Floating on the gentle current

Dreamily it swam in the spring.

Will you take it home

And pin it to your bosom, Marie;

Behind its petals hides

A deep and calm wave.

Child, be wary of the current in the brook,

Dangerous it is to dream there!

The water-sprite pretends that he is sleeping;

Lilies play above.

Child, your breast is the current of the stream.

Dangerous it is to dream there!

Lilies play above,

The water-sprite pretends that he is sleeping.

The mood somewhat lightens in the fourth song titled “With a Water Lily.” Yet, below the playfulness in both the poem and music, there is a hint of darker forces, and the symbol of the water-sprite is used once again. The accompaniment seems to make a nod towards Schumann, and the vocal part is doubled in both hands for the entire song. It has been described as “racing off like thoughts ahead of the spoken word, to be brought back to heel by the voice.”

Edvard Grieg’s 6 Poems by Henrik Ibsen, Op. 25

The supernatural water sprite appears in the third stanza of the poem and, in this sense, represents the dangers of love. The music mirrors this danger by plunging from a charming melody into the darker minor mode. The melody is taken down in spiralling chromatic phrases through various transitions, with the music eventually returning to the playful opening. “The song, unlike the poem, ends with a sense of happiness and security.

We accompanied the last guests to the gate;

The night wind took the last farewells.

Tenfold deserted lay harbour and house,

Where, previously, the music had intoxicated me.

It was a feast just before the black night;

She was only a guest and now she is gone.

“Gone” presents a brief and elusive world. The desolation of the house and garden mirrors that of the poet, and it has been suggested that with this concise poem, “Ibsen could rival Heine in conveying vivid impressions with great simplicity.” In only 13 measures, Grieg captures the haunting quality once more in short phrases and in a recitative-like style of declamation.

A Birdsong

On a lovely spring day we walked up and down the avenue;

The forbidden step drew me like a mystery.

And the west wind blew and the sky was blue;

In the limetree a mother-bird sat and sang for her young.

I painted poetic images with playful brushstrokes;

Two brown eyes shone and smiled and listened.

Above us we can hear twittering and merriment;

But we two took a fond farewell and never met again.

And as I wander alone up and down the avenue

I am never left in peace by the little feathered creatures.

Mistress sparrow has been sitting and listening while we innocently walked

And she has written a poem about us and set it to music.

It is in the bird’s mouth; for under the leafy roof

Every beak sings of the bright spring day.

The concluding song conveys a truly playful mood. The poem tells of two lovers meeting under the trees while the birds watch and sing around them. It is reported that Ibsen wrote the poem when he was in love with a sixteen-year-old girl. When they were caught, “Ibsen with heroic timidity apparently ran away.” In Grieg’s setting, this peaceful and cheerful song provides a new spring “after a dark and hard winter.”

In his Six Poems by Henrik Ibsen, Edvard Grieg was clearly not inspired by the poet’s flight of fantasy but rather by the text’s austerity and seriousness. These short, autumnal pictures are written in a highly charged symbolic language, as the text and music relate to how life’s crises can only be overcome with the aid of music.