by Georg Predota , Interlude

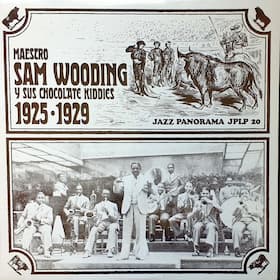

Sam Wooding and his Chocolate Kiddies

Just a couple of years after Western Europe fell under the spell of popular American musical styles, it also debuted in the Soviet Union. As a musical language increasingly placed at the service of social commentary, and with its strong connotations for freedom, jazz in the Soviet era led a somewhat tortured existence. Constantly in flux between prohibition, censorship and even state sponsorship, jazz developed into a popular form of music and it became an element of Soviet cultural life. The birth of Soviet jazz is celebrated on 1 October 1922 when Valentin Parnach and his band played their first concert in Moscow.

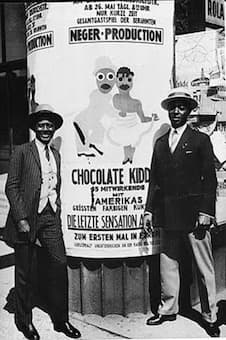

Chocolate Kiddies poster

Parnach came into contact with jazz at a concert of the American band Louis Mitchel Jazz Kings during his exile in Paris in 1921. He returned to Moscow a year later with a complete set of instruments. But what really got the jazz craze properly started were appearances of bandleader Sam Wooding and his “Chocolate Kiddies.” Essentially a Broadway-styled revue billed as a “negro operetta,” it toured the Soviet Union in 1926 for three months with appearances in Moscow and Leningrad. Joseph Stalin was in the Moscow audience, and criticism focused on the visual aspects of the performance. As a reviewer wrote, “it is not important how blacks play, how they dance, sing and think… What is important is that they are all black.”

Sam Wooding & his Chocolate Kiddies in Leningrad

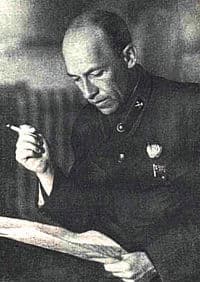

Dmitri Shostakovich

When the Chocolate Kiddies Company arrived in Leningrad, a highly interested Dmitri Shostakovich sat in the audience. According to musicologists, this “was, to Shostakovich a musical revelation of America.” Growing up in the young Leninist Soviet Union, Shostakovich had previously only gleaned jazz through selected friends and sparse historical information. The vitality and enthusiasm of the performers made an indelible impression, and jazz remained part of his compositional toolkit. Political circumstances beyond his control made it impossible to overtly practise his appreciation, but in 1934 he was commissioned by a Leningrad dance band to furnish some dancing music. The resulting Suite for Jazz Orchestra is a whimsical take on jazz, reflecting more of the composer’s interest in gypsy music and the music of the Yiddish theatre. As such, we expectedly find a waltz and a polka, but it also features a concluding foxtrot. Conforming to severe Soviet guidelines, this jazz suite leaves no room for improvisation but unfolds in strict time and rhythm.

May Day in Leningrad (1925)

The Soviet Union experienced massive political and economic upheavals in the early 1930s, and jazz was eyed as an undesirable import of Western culture. Joseph Stalin tightly controlled all manner of artistic expression, and he demanded that all forms of art convey the struggles and triumphs of the proletariat and present a realistic reflection of Soviet life and society. Searching for a musical style “in which the ideology of the emerging communist communal society could be expressed most effectively” also meant that jazz had to be politicized.

Isaak Dunayesky

Maxim Gorki, writing during his exile in Sorrento, equated jazz with homosexuality, drugs and eroticism. He describes jazz as “a dry knock of an idiotic hammer penetrates the utter stillness. One, two, three, ten, twenty strikes, and afterwards a wild whistling and squeaking as if a ball of mud was falling into clear water; then follows a rattling, howling and screaming like the clamor of a metal pig, the cry of a donkey or the amorous croaking of a monstrous frog. The offensive chaos of this insanity combines into a pulsing rhythm. Listen to this screaming for only a few minutes, and one involuntarily pictures an orchestra of sexually wound-up madmen, conducted by a Stallion-like creature who is swinging his giant genitals.” The alleged connection between jazz, modern dance and sexuality was officially classified as “sonic idiocy in the bourgeois-capitalist world.” Given such overt hostility, jazz idioms found refuge in motion pictures.

Sergei Prokofiev

With Soviet artists and performers increasingly falling under the microscope of uncompromising state machinery, Sergei Prokofiev—with permission from the government—packed his bags and settled in Paris in October 1923. In a city awash with artistic personalities, Prokofiev quickly became interested in jazz and rubbed shoulders with leading composers, including George Gershwin in 1928. Vernon Duke reports, “George came and played his head off; Prokofiev liked the tunes and the flavoursome embellishments, but thought little of the Concerto in F, which he said later, consisted of “32-bar choruses ineptly bridged together.” Prokofiev thought highly of Gershwin’s gifts, both as a composer and pianist, and he predicted “he’d go far should he leave dollars and dinners alone.” Duke also remembered Prokofiev saying, “Gershwin’s piano playing is full of amusing tricks, but the music is amateurish.” Prokofiev met Gershwin again in 1930 in New York, and noted in his journal afterward, “Gershwin also attempts to compose serious music, and sometimes he even does that with a certain flair, but not always successfully.” For all the criticism and posturing, it is clear that Prokofiev was highly receptive to jazz influences. One might actually describe the slow movement of his Third Piano Concerto, a work that had been started as far back as 1913, as greatly indebted to Gershwin.

For much of his career and life, Beethoven was struggling financially. He would on occasion make a shedload of money, which he tended to invest in bank shares. However, the severe depreciation of the Austrian currency as a result of the extended Napoleonic war, slashed his wealth by over fifty percent, and it also significantly reduced the value of the annuity paid to him by Archduke Rudolph, and the Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky. And even when Beethoven was relieved from any rational grounds for financial worry, he was constantly apprehensive about his financial situation.

For much of his career and life, Beethoven was struggling financially. He would on occasion make a shedload of money, which he tended to invest in bank shares. However, the severe depreciation of the Austrian currency as a result of the extended Napoleonic war, slashed his wealth by over fifty percent, and it also significantly reduced the value of the annuity paid to him by Archduke Rudolph, and the Princes Lobkowitz and Kinsky. And even when Beethoven was relieved from any rational grounds for financial worry, he was constantly apprehensive about his financial situation.