By Georg Predota, Interlude

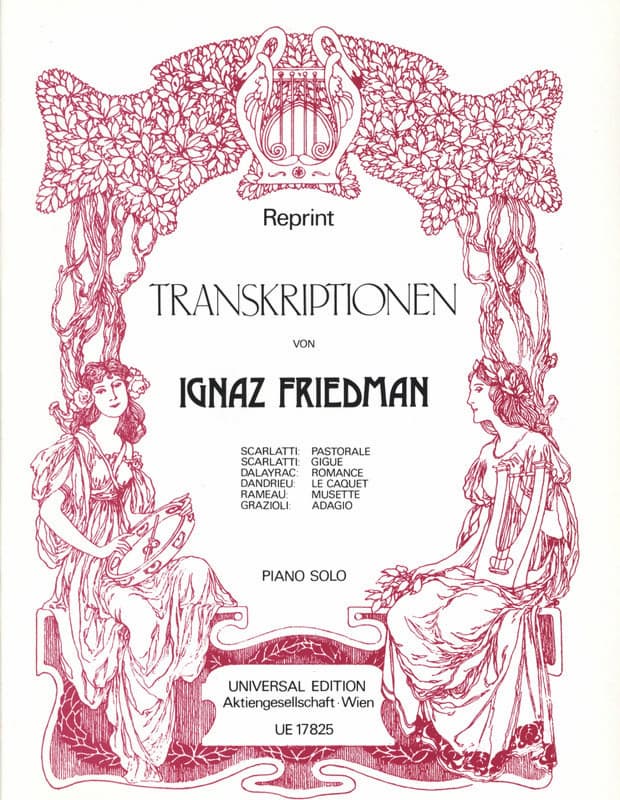

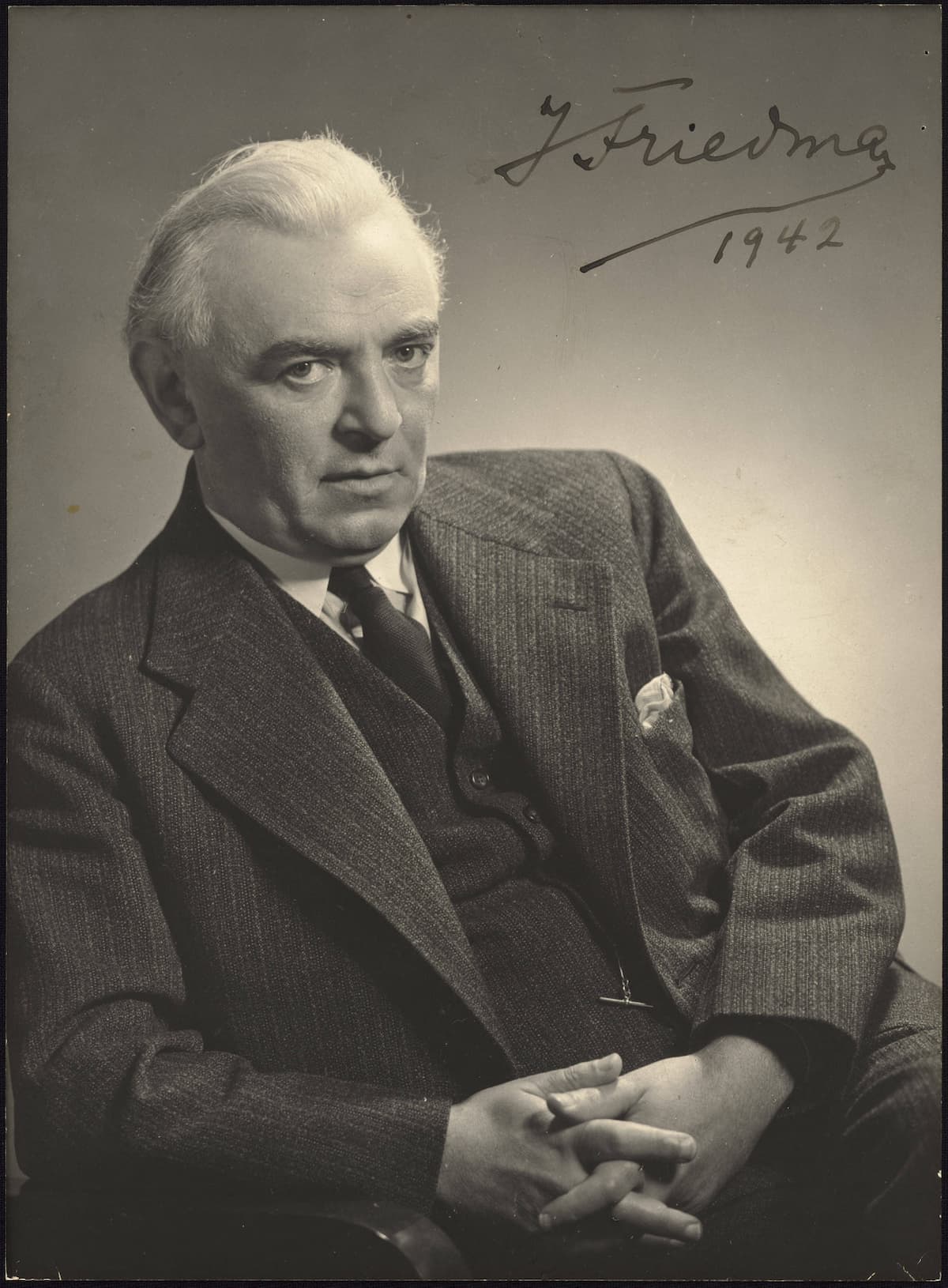

Ignaz Friedman

Not to be outdone, Vladimir Horowitz described him as his technical superior and added “Ignaz Friedman was a great artist. He had wonderful fingers and a very personal, individual way of playing, even if some of his ideas were very strange to me.” It is less well-known that Friedman was an astute editor. He issued the complete works of Chopin, earning high praise from Claude Debussy. Friedman also edited a number of works by Schumann and Liszt alongside Bach’s Inventions and Sinfonias and produced a large number of transcriptions and arrangements. His genius as a pianist, however, has greatly overshadowed his work as a composer. The vast majority of his roughly 90 works are essentially unknown today. I believe it’s high time to meet Ignaz Friedman the composer. So let’s get started with Friedman’s set of variations on a very popular theme by Paganini.

Transcription by Ignaz Friedman

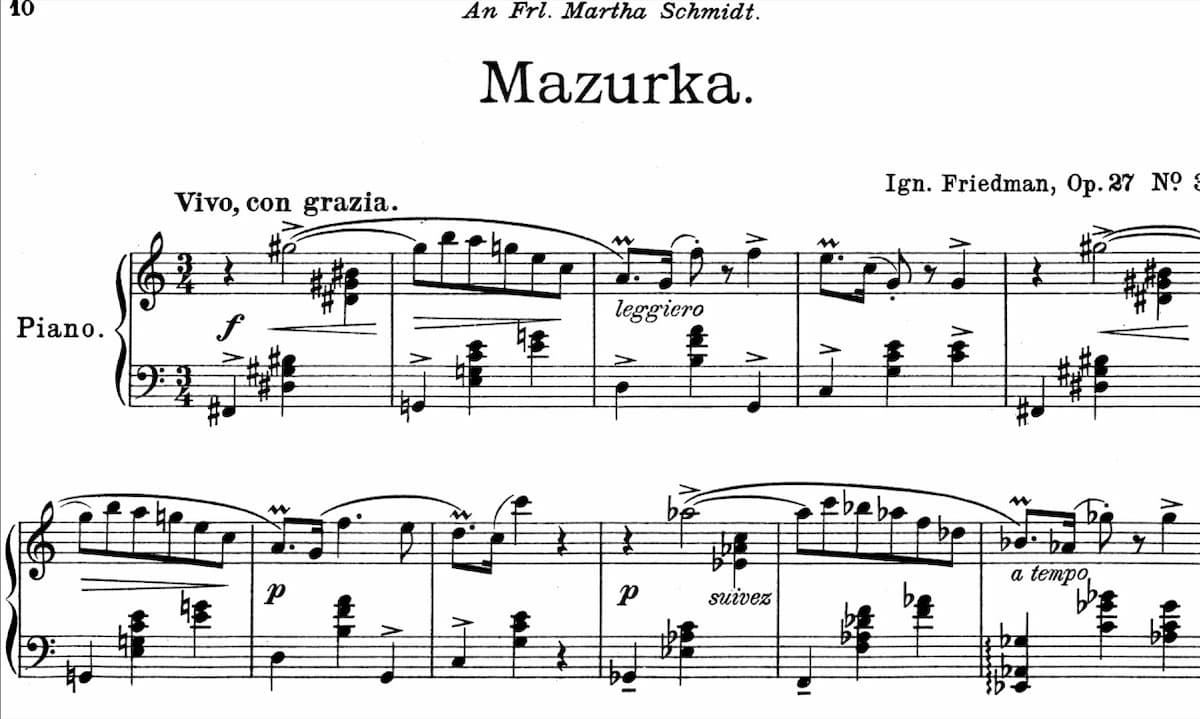

Friedman was a child prodigy with incredible pianistic potential, and he also appears to have started composing at an early age. The earliest mention of an original composition, played by Friedman in a concert on 11 March 1898 makes mention of a piano trio. The critic writes, “Friedman’s trio for piano, violin, and cello shows talent but elements of the composer’s talent should be kept aside until he’s mature to produce something artistically valid.” That particular composition did not survive, and it may well have been destroyed after Friedman read the review. We do know that he studied composition privately with Hugo Riemann in Leipzig. In fact, Riemann presented a reference letter to Friedman. “Herr Ignaz Friedman was my student in piano and composition from the autumn of 1900 until the autumn of 1901. I gladly attest to the fact that he has a very strong talent for the profession of musician… Also in original composition, he has shown talent and considerable promise.” Friedman would soon include his original compositions in his recital programs, such as the four piano pieces Op. 27, which “possess the melodic invention of the character pieces of Schumann, Grieg, and Brahms with the lush harmonic inventiveness of Chopin, Scriabin and Rachmaninoff mingling with some Polish folkloric inspiration.”

While salon pieces for domestic consumption presently don’t rank particularly high, they were once the foundation of an entire musical culture. It is worth remembering that outstanding composers and performers wrote salon pieces that contained musical allusions, jokes, and even brief moments of contemplation. After all, they addressed highly educated and artistically inclined audiences. It was left to the technical skill of the professional performer to “bring out the modulations, diversify the sound, introduce subtle shades of articulation, and highlight the changing moods.” They are not merely museum pieces, but a significant part of Western musical heritage. Yet their reception history has been less than kind from the very beginning. Karol Szymanowski complained about Friedman’s works being printed on the verso of his score. He writes, “It always irks me to see on the final page of my Sonata and Variations the list of hundreds of Friedman’s horrible ditties; I admit it is childish of me, but I gladly admit it. Friedman’s five charming waltzes for piano four hands date from 1912, and these “ditties” are saturated with pianistic gestures best left to the professionals.”

For Harold C. Schonberg, a renowned and long-time critic of the New York Times, music “begins with Bach, Handel, and Gluck.” As he once wrote, “I do not want a modern approach to Bach, I want Bach’s approach to Bach.” Schoenberg greatly admired Friedman the pianist, and probably also Friedman’s Passacaglia in F minor, Op. 44, dedicated to his fellow pianist Josef Hofman. The work begins in the style of Bach with a statement of the passacaglia theme in the base. However, the chromatic nature of Friedman’s theme provides some indication of the bold developments to come. Initially, the theme is kept in the bass but soon transfers to the right hand with an increasingly fast accompaniment. Not entirely unexpected, Friedman presents an inverted version of the theme almost entirely obscured by dense chromatic harmonies. It takes a power tremolando for the main theme to return to the bass register. Some additional counterpoints and deceptive cadences bring the work to a simple close in F major. A commentator wrote, “With a final suggestion of the theme landing on an E flat, could it have possibly been a tribute to the end of Chopin’s F Major Prelude?”

Ignaz Friedman’s Mazurka score

For Schonberg, “Friedman’s style was completely his own, and it was marked by a combination of incredible technique, musical freedom (some called it eccentricity), a tone that simply soared, and a naturally big approach, with dynamic extremes that tended to make a Chopin mazurka sound like an epic. He handled a melodic line inimitably, deftly outlining it against the bass, never allowing it to sag, always providing interest with a unique stress or accent. As he thought big, he played big. Friedman was a force, a powerful, unusual, original pianist, sometimes erratic but always fascinating, and always full of imagination and daring.” Friedman’s native affinity with the Mazurka is heard not only in his rousing recordings of Chopin mazurkas but also in a series of his own mazurka compositions, which combine pianistic and compositional refinement with idiosyncratic, rustic charm. The originality and beauty of the Friedman mazurkas confirms that he was a master of the character piece. Although harmonically complex yet always tonal, Friedman lets the beauty and poignancy of the melody shine through, while rhythm becomes a signpost to the genre. As a performer writes, “Pianistically accessible, Friedman’s works demand technical and musical perfection.”

I

For Friedman, Poland evoked poverty and anti-Semitism, yet it also provided his cultural base. As a pianist, he represented the musical culture of Vienna and Berlin, “and to a lesser extent, Poland, the land of his origins, which had “imposed upon him the dual status of Pole and Jew.” Friedman spoke Polish elegantly, “infused with archaisms inspired by romantic poets.” He was an ardent supporter of Polish autonomy, but he never considered returning to live in Poland after it had gained independence. Situated between self-destructive Russia and militarist Prussia, Poland had been partitioned. Foreign occupation led to “the air in Poland always being oppressive; one breathes in elements of melancholy there that constrict the heart, and one always has the feeling that life is not completely real.” Friedman and his generation remained undisturbed by Modernism. “His sympathy was with the rural culture of Poland, first shaped while dancing with peasants in their villages… He felt very much Polish, down to earth, not intellectually, but really felt the power of the earth.”

Friedman’s compositions possess great melodic beauty and harmonic inventiveness, clothed in the character of the late Romanticism. Composed in 1918, Stimmungen (Moods) presents nine instrumental poems dedicated to Sergei Rachmaninoff. Friedman enjoyed a cordial relationship with Rachmaninoff, who tried to invite him for a visit to his house in New York in 1927. Rachmaninoff writes, “Evidently, to receive you as a guest is as difficult as buying asparagus at Christmas. I propose the following. It is possible to come for dinner on 30 December? I promise to release you at ten so you can go and play cards.” Rachmaninoff’s musical and technical influence is clearly audible in this set, as is Friedman’s love for the pensive and passionate music of Grieg, and the city of Vienna. The German title “Stimmung” implies harmony between the instrument and an internal spiritual condition. Friedman projects a number of moods connected to Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Grieg, and Scriabin. “The mysterious and soulful final piece is a small set of variations in Russian style with lush harmonic wanderings that bring the set to a somber close.”

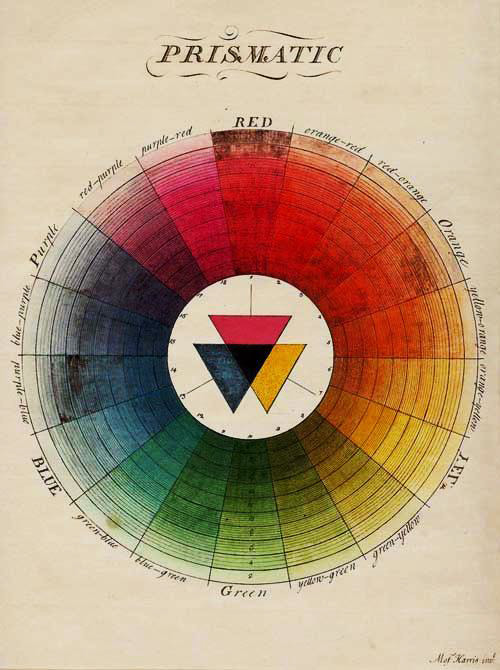

Commentators and critics tended to focus on Friedman’s technical prowess. Joseph Marx writes, “Weightlessly, his hands glide on the keys, his fingers move only as much as necessary, every small movement is controlled. Everything seems so effortless that pianistic problems disappear like snow in the sun. One can hardly follow him as his hands run over the keys so quickly. Nevertheless, everything remains so clear, as though a light veil covered the playing and removed the brilliance, a certain shiny tone that salon players sometimes have. But I don’t say to myself that it is a mistake, on the contrary. The shadings in the pianissimi are astonishing as the scale goes from p to pppp, as rich as his poco forte to fff.” And the leading Hungarian critic Aladar Toth added, “Compared to mechanical technique, Friedman’s technique is a true recreation in its poetic, unconstrained, and impulsive free variety… The sensuous magic of the piano sounds could almost daze or even fool the listener for minutes. But the old mixer of tone colors doesn’t give up and spreads out the silks and velvets and expensive furs to an ever-dwindling public. However, Friedman’s most infamous charlatanisms have more in common with art and poetry than those young bravura player who, with their factory-made techniques, earn millions of dollars in America.”

Friedman’s Vienna debut on 22 November 1904 created a sensation after he played three virtuoso piano concerti, Brahms D minor, Tchaikovsky B-flat minor, and Liszt E-flat major. The teenage Friedman had come to Vienna to study with the famed Theodore Leschetizky, himself a student of Carl Czerny. Initially, Leschetizky told him “that he would be better off to play tuba,” and sent him to his assistant Malwine Brée. Essentially, Brée helped students solve mechanical problems, and she “offered a pragmatic and musical wrist exercise to develop an even touch.” Friedman later said that “it all began with a definite technical scheme, but that only went so far as great piano playing is concerned. It was only the beginning, which every pianist should have. Then the greatness of Leschetizky came in.” Eventually, Friedman became Leschetiziky’s favorite student, and he appointed him as an assistant. Leschetizky later said that Friedman “possessed the three prerequisites needed to make a great musician: Slavic origins, Jewish heritage, and child prodigy.” During his Vienna years, Friedman performed a number of transcriptions by Schulz-Evler and Godowsky, and he set to work on a number of themes sung by Viennese court opera baritone Eduard Gärtner.

Ignaz Friedman: 6 Wiener Tänze nach Motiven von Eduard Gärtner (Joseph Banowetz, piano)

Friedman’s Piano Quintet score

Among the surviving Friedman compositions, his Piano Quintet in C minor is regarded as his finest piece. Composed in 1918, the circumstances surrounding the compositions are still vague, but it “has been suggested that it may have been inspired by the death of the composer’s father and that the theme of the third movement, derived from Polish folk music, maybe a tribute to him.” We do know, however, that the work is dedicated to Maria Christina, Archduchess of Austria and Queen Regent of Spain. The somber mood of the opening movement might well have been inspired by the horror of World War I, “while the melancholy ending might be a musical glance at a world that had gone forever.” That melancholy is most prominently heard in a waltz-like section that might have come straight from Strauss’ Rosenkavalier. The expressive second movement features an expansive set of themes and variations. The theme is basically a succession of three short motifs, and every successive variation sounds like an independent miniature. The concluding finale is titled “Epilogue,” and features a Polish folk tune that undergoes a number of transformations. Naxos Music has issued the complete recordings of Ignaz Friedman between 1923 and 1941, and a number of performers have taken on his compositions. Together, we are finally getting a more complete picture of one of the greatest musicians of the 20th century.