by Rudolph Tang, Interlude

Music by living composers creates a tangible connection between artistic expression and the world I inhabit. This connection often feels more immediate than the distant echoes of classical music from centuries past. I also relish conversations with composers, uncovering the ideas and inspirations behind their works. These exchanges enrich my understanding of contemporary music—a privilege I hold dear.

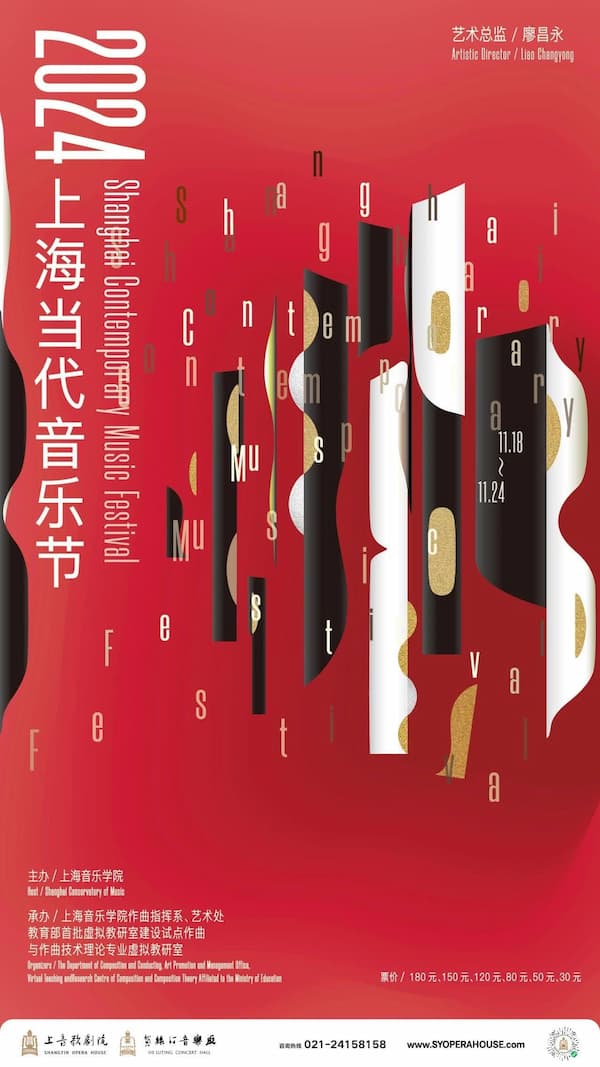

As the Beijing Modern Music Festival, once the flagship of China’s contemporary music scene, struggled with funding in 2024, the Shanghai Contemporary Music Festival emerged as a potential standard-bearer. Revamped and re branded from the former Shanghai Contemporary Music Week, this week-long festival, held in mid-November 2024, showcased a diverse and compelling program. It featured Western luminaries such as Kaija Saariaho, Henri Dutilleux, and Sofia Gubaidulina, alongside Asian trailblazers like Toru Takemitsu, Xiaogang Ye (葉小剛), and Shande Ding (丁善德).

The festival also highlighted works by its three composers-in-residence: Jiping Zhao (趙季平), Tristan Murail, and Mengdong Xu (徐孟東). Orchestral works from these and other leading composers were performed by four exceptional ensembles: the Suzhou Symphony Orchestra, Shanghai Philharmonic Orchestra, Shanghai Opera House Orchestra, and the newly founded Wuxi Chinese Orchestra.

These performances took place at the Shangyin Opera House, affiliated with the Shanghai Conservatory of Music (SCM). While the venue’s acoustics, designed for opera, resulted in a dry sound that challenged conductors to convey the intricate nuances of orchestral works, the performances were nonetheless remarkable.

Emerging composers took center stage in a chamber music concert that premiered nine new commissions from faculty members of SCM’s mighty Composition Department. Among these were works by three female composers, a testament to the festival’s commitment to its ongoing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiative.

In total, the festival introduced 85 works by 80 composers to live audiences through a rich tapestry of concerts, seminars, lectures, and forums. It has truly become a one-stop destination for anyone with a keen eye and fine-tuned ears for contemporary music.

Here are five of the most arresting pieces from the concerts I attended.

Ye Xiaogang: Du Fu’s Thatched Cottage

Ye Xiaogang remains China’s most performed living composer—and with good reason. Often overrun with commissions, he’s a figure so in demand that it’s not uncommon for his music to be performed in two different venues on the same evening, with him expected to appear at both.

Ye Xiaogang © Wikipedia

Despite his prominence and political influence, Ye’s music speaks entirely for itself. Rich in texture and profound in its storytelling, his compositions encapsulate the timeless depth of Chinese intellectualism. For instance, Songs of the Earth offers a contemporary lens on the same Tang poetry that inspired Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, blending tradition with modern sensibilities.

If Songs of the Earth stands as Ye’s crown jewel in the lieder genre, Du Fu’s Thatched Cottage is undoubtedly his magnum opus. In this work, Ye transforms Du Fu’s austere and unyielding poetry into music that is equally forceful and resolute, delivering a powerful statement of endurance and spirit.

Zhou Xianglin (周湘林): Da Jia Ye (Build a Family Fortune) for Tujia Percussions and Orchestra

When it comes to blending Chinese ethnic musical elements with a symphony orchestra, Zhou Xianglin stands as a trusted master. Known for composing concertos for traditional Chinese instruments like the ruan, erhu, and various percussion ensembles, Zhou skillfully harnesses the full power of orchestral richness while preserving the authenticity and spirit of ethnic music. His works often breathe new life into folklore popular among China’s minorities, adding an extra layer of sophistication to an already vibrant instrumental landscape.

Zhou Xianglin © en.riversawards.cn

Da Jia Ye, inspired by the celebratory percussion music of the Tujia ethnic group, showcases Zhou’s vision of East-meets-West. Drawing on the rhythmic power of traditional gongs, tam-tams, and small cymbals, the piece weaves these ethnic sounds into the fabric of a modern orchestra. The composition builds gradually, with a deliberate orchestral escalation that culminates in a breathtaking, celebratory coda, a tribute to masculine strength and communal festivity.

Chen Musheng (陳牧聲): La Mémoire, Cello Concerto

In 1911, Dr. Sun Yat-sen led the revolution that toppled the Qing dynasty, ending centuries of imperial rule and sending the Last Emperor into exile (immortalised in the Academy Award-winning film The Last Emperor). This revolution paved the way for the Republic of China, laying the groundwork for modern China’s political evolution. The momentous 1911 Revolution became the inspiration for Chen Musheng’s first cello concerto, composed in 2011 and dedicated to the centennial of this historic uprising—the first of many revolutions that shaped China’s trajectory.

Chen Musheng © musinfo.ch

The concerto’s current iteration, retitled La Mémoire, is based on Chen’s 2013 revision, reflecting the composer’s years studying music in France. By shedding its original title, the five-movement work transcends its commemorative roots to become a deeply personal exploration, intertwining Chen’s life journey with the struggles and triumphs of revolutionary pioneers.

The first movement, somber and tender, takes the form of a requiem. It offers a rare moment of introspection, standing apart from much of contemporary Chinese composition. In La Mémoire, Chen weaves a narrative that is both personal and historical, creating a poignant homage to memory, sacrifice, and transformation.

Gubaidulina: Introitus

Referring to the introductory chant of the Mass in the Roman Catholic liturgy, Gubaidulina’s Introitus finally received its long-overdue Chinese premiere nearly half a century after its debut in 1978 during the composer’s creative zenith. The Shanghai audience was fortunate to witness this extraordinary performance, with Alice Di Piazza – an undisputed piano concerto queen- delivering the solo with unmatched grace and intensity.

Sofia Gubaidulina

It was nothing short of a miracle that this deeply spiritual piece imbued with a profound sense of piety and benevolence, found its way to the stage in mainland China. The performance marked not just a milestone in musical programming but also a rare moment of artistic reverence.

Tritan Murail: Le Partage des Eaux

Tristan Murail © wihuriprizes.fi

It would only be fitting to call Tristan Murail a titan of spectral music, or perhaps even its very personification, as one of its co-founders. His masterpiece, Le Partage des Eaux, received its much-anticipated Chinese premiere during the festival, offering the captivated audience a taste of the extraordinary complexity and depth that defines this genre.

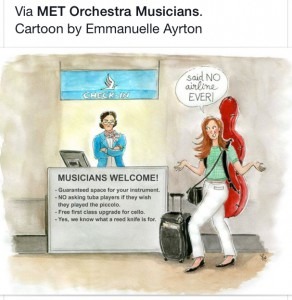

In another instance Yuki Manuela Janke was returning home to Germany after giving a performance in Tokyo, when customs officers at the Frankfurt airport confiscated her 1741 Stradivarius violin worth $7.6m claiming Janke might plan to sell it. If she wanted it back she’d have to pay $1.5m customs duty. The instrument known as ‘The Muntz’ violin had been leased to Janke since 2007 and the owners, the Japan-based Nippon Foundation, indicated that Janke had documentation, including her loan contract with the foundation, photographs of the violin, and other papers.

In another instance Yuki Manuela Janke was returning home to Germany after giving a performance in Tokyo, when customs officers at the Frankfurt airport confiscated her 1741 Stradivarius violin worth $7.6m claiming Janke might plan to sell it. If she wanted it back she’d have to pay $1.5m customs duty. The instrument known as ‘The Muntz’ violin had been leased to Janke since 2007 and the owners, the Japan-based Nippon Foundation, indicated that Janke had documentation, including her loan contract with the foundation, photographs of the violin, and other papers.