Johann Sebastian Bach’s music stands as a towering monument in Western music. While countless composers have written exceptional choral music, Bach’s greatest choruses intertwine technical perfection and profound emotional resonance to create moments of transcendent beauty.

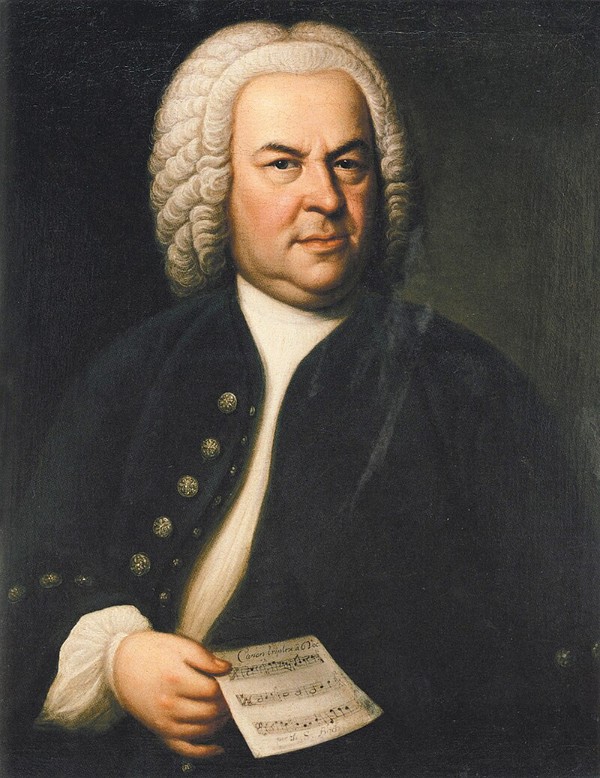

Portrait of J.S. Bach

Christmas Oratorio

Bach’s choruses are not merely perfect technical exercises but living expressions of human devotion, of joy and sorrow, and of awe. Every chorus pulses with intricate counterpoint, vibrant harmonies, and a transcendent ability to connect with something much greater.

To commemorate Bach’s death on 28 July 1750, let us celebrate his life by featuring 10 of his greatest choruses, starting with the opening chorus from the Christmas Oratorio. It bursts forth with an exultant energy that feels like the heavens themselves are rejoicing.

The vibrant timpani rolls and blazing trumpets create a majestic, almost overwhelming wave of sound, as if heralding the arrival of divine light. The choir’s jubilant voices weave through Bach’s intricate counterpoint, each line soaring with unbridled joy and reverence, inviting the listener into a sacred celebration that transcends time.

It’s a moment of awe, where the grandeur of music and spiritual depth converge to proclaim eternal hope.

Reformation Glory

A postcard featuring Johann Sebastian Bach

Composed for Reformation Day, “A might fortress is our God” is one of Bach’s most powerful and intricately constructed choral works. The cantata draws on Martin Luther’s iconic hymn, a cornerstone of the Lutheran tradition that celebrates God’s unyielding strength and protection against spiritual and worldly adversaries.

The opening chorus burst forth with an electrifying energy. The choir enters with a commanding declaration before breaking into intricate counterpoint. This creates a sense of unity and strength, with the unshakable foundation of the hymn melody surrounded by layers of complexity symbolising the multifaceted nature of faith.

The emotional resonance of this chorus lies in its ability to balance grandeur with intimacy. While the intensity of the music evokes the image of a cosmic battle, Bach also projects moments of exquisite tenderness, creating a fleeting sense of warmth and reassurance. This chorus is a spiritual journey with all of humanity united in a final, triumphant cadence.

Plea for Peace

The “Dona nobis pacem” chorus, which closes Johann Sebastian Bach’s monumental Mass in B Minor, is a profound and awe-inspiring culmination of one of the greatest works in Western music. It emerges as a fervent plea for peace, its majestic simplicity and emotional resonance encapsulating an unbelievable spiritual and musical journey.

Bach employs a double fugue that weaves together two distinct themes. A broad and soaring melody is combined with a more intricate and rhythmic idea, making the tapestry of sound feel both universal and deeply personal.

This fugue structure, with its intricate interplay of voices, showcases Bach’s unparalleled technical skill. Yet, the technical complexity never overshadows the heartfelt supplication of the text. The repeated phrase “Grant us peace” is delivered with a rhythmic insistence that actually feels like a heartbeat, grounding the music in a deeply human appeal.

Jubilant Proclamation

J.S. Bach featured on a stamp design

The opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata BWV 147, Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben (Heart and Mouth and Deed and Life), is a radiant and jubilant proclamation of faith, composed in 1723 during Bach’s first year in Leipzig. The chorus bursts forth with an infectious vitality that perfectly embodies the cantata’s theme of wholehearted devotion.

Bach’s masterful interplay of voices and instruments creates a soundscape that feels both majestic and intimate, inviting the listener into a profound expression of spiritual commitment. Structurally, the chorus is a choral fantasia, built around a chorale tune placed in the soprano as long and sustained notes.

The other voices engage in intricate, imitative counterpoint, weaving a web of motivic interplay that reflects the text’s call to every aspect of life to testify to faith. The emotional resonance of the chorus lies in its balance of exuberance and sincerity. The text’s emphasis on holistic devotion is mirrored in the music’s all-encompassing energy, with each vocal and instrumental line contributing to a unified expression of faith.

Splendour and Sorrow

Composed in 1724 for Good Friday services in Leipzig, the opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion “Lord our Ruler,” erupts with tempestuous energy. One of Bach’s most dramatic and emotionally charged works, its swirling orchestral textures and urgent vocal lines beautifully capture the profound reverence of the Passion narrative.

Bach’s music masterfully balances awe for Christ’s divine majesty with an undercurrent of sorrow for the impending crucifixion, creating a soundscape that is both regal and deeply human. The orchestra, with its driving strings, plaintive oboes, and pulsing continuo, sets a restless, almost turbulent tone, while the choir’s powerful entrance amplifies the sense of cosmic significance, drawing the listener into the sacred drama.

Bach constructs this chorus as a complex, quasi-fugal edifice, with the voices entering in waves of imitative counterpoint that mirror the text’s invocation of Christ’s eternal glory. He uses dark and expressive minor tonalities with chromatic inflexions and dissonant suspensions to heighten the emotional impact. It all culminates in a radiant cadence, however, as Bach assures us of divine triumph.

Triumphant Awakening

The Triumphant Awakening of Bach’s opening chorus from the cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, is a radiant and exhilarating call to spiritual vigilance. Inspired by the parable of the wise virgins awaiting the bridegroom, the chorus bursts forth with a sense of urgency and joy.

The majestic orchestral introduction is driven by a lively dotted rhythm, and the soaring melodic lines evoke a divine summons. The orchestra, featuring strings, oboes, and a prominent horn, creates a festive, almost ceremonial atmosphere, with syncopated rhythms and fanfare-like figures that pulse with expectancy.

Here, as elsewhere, Bach seamlessly blends grandeur and intimacy, with the cosmic significance of Christ’s arrival balanced by lyrical moments that evoke personal devotion. As voices and instruments unite in a triumphant close, the music becomes a stirring summons to spiritual awakening, its exuberance and craftsmanship leaving listeners uplifted by Bach’s vision of divine anticipation.

Defiant Joy

Bach’s statue in Leipzig

The opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata BWV 4, Christ Lay in Death’s Bonds, is a gripping and jubilant proclamation of Christ’s victory over death. Based on the Easter hymn by Martin Luther, the stark yet radiant orchestration establishes a tone of both solemnity and exultation.

The text celebrates the Resurrection, and Bach’s music captures this duality with a masterful blend of archaic severity and vibrant optimism. Luther’s hymn melody is woven through the texture in long, sustained notes, serving as an anchor of faith amidst the intricate polyphony of the other voices.

The minor tonality lends a sombre, almost austere quality, reflecting the gravity of Christ’s sacrifice, but Bach infuses it with bright, major-key inflexions at key moments, particularly when the text symbolises the light of resurrection. It is a cosmic affirmation of life over death.

Celestial Joy

The opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata BWV 1, How Brightly Shines the Morning Star is a jubilant celebration of Christ, who brings divine light to humanity. This chorus bursts forth with an effervescent energy, its orchestral introduction featuring a sparkling interplay that evokes the shimmering brilliance of a starlit dawn.

The text, based on Philipp Nicolai’s 1599 hymn, exudes joy and hope, and Bach’s music amplifies this with a festive, almost dance-like vitality. The choir’s proclamation radiates warmth and devotion, drawing us into a moment of spiritual awe and exultation.

As in his other choral fantasias, Bach presents the hymn melody in long and sustained notes in the soprano, while the lower voice weaves intricate counterpoint that pulses with energy and delight. The festive scale of the music conveys the cosmic significance, while tender vocal interplay evokes personal devotion. It is a radiant testament to Bach’s ability to translate theological joy into sounds of transcendent beauty.

Heavenly Exultation

The opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata BWV 191, Gloria in excelsis Deo, is a resplendent and jubilant outburst of praise. This chorus radiates with a festive brilliance, its orchestral texture ablaze with trumpets, timpani, flutes, oboes, and strings that create a sonic tapestry of divine celebration.

Bach captures the text drawn from the Latin Mass with an irrepressible energy that feels like a heavenly fanfare. From the opening measures, the orchestra establishes a mood of unrestrained joy, while the entrance of the choir as a unifying and exultant force draws us into a moment of awe-inspired worship.

This masterful choral fugue showcases Bach’s unparalleled skill in blending technical complexity with emotional accessibility. The interplay of voices and instruments is seamless, and the balance between grandeur and heartfelt devotion culminates in a radiant and triumphant universal hymn of praise. What an unbelievable vision of divine glory!

Divine Innocence

The opening chorus of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, is a monumental and deeply moving introduction to one of the most profound works in Western music. Set in the minor key, this chorus immediately immerses the listener in the Passion’s dramatic and emotional landscape, blending heart-wrenching sorrow with awe-inspiring grandeur.

The orchestral introduction, with its pulsating, syncopated rhythms and mournful string lines, evokes the weight of impending tragedy, with the entrance of the choir imploring the daughters of Zion to join in lamentation.

It’s pure genius, as Bach actually employs two choirs engaging in a dialogic interplay, their voices weaving together in a dense, imitative texture that reflects the communal mourning of Christ’s sacrifice. The emotional power lies in Bach’s ability to balance raw sorrow with transcendent majesty, setting the stage for the Passions’ profound exploration of sacrifice and salvation.

Bonus Chorus

It’s impossible to design a playlist of Bach’s 10 greatest Choruses without the serene devotion of “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” Part of Cantata BWV 147, it is one of Bach’s most beloved and enduring works as it exquisitely balances simplicity with sophistication.

The choir’s straightforward presentation of the chorale melody, with its clear, hymn-like phrasing, anchors the movement in a direct expression of faith, while the orchestra’s continuous, lilting triplet figures add a layer of delicate complexity, symbolising the constant presence of divine grace.

Johann Sebastian Bach’s 10 greatest choruses stand as towering testaments to his unparalleled genius, blending technical virtuosity with profound emotional and spiritual resonance. His mastery of counterpoint, innovative orchestration, and expressive harmonies creates a timeless dialogue between faith and artistry, affirming Bach as one of history’s greatest musical architects.