It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Showing posts with label Georg Friedrich Händel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Georg Friedrich Händel. Show all posts

Sunday, September 28, 2025

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

Top 10 Baroque composers

From around 1600 to 1750, the Baroque period witnessed the creation of some of the greatest musical masterpieces ever composed. Here's our beginner's guide to the greatest composers of the Baroque period

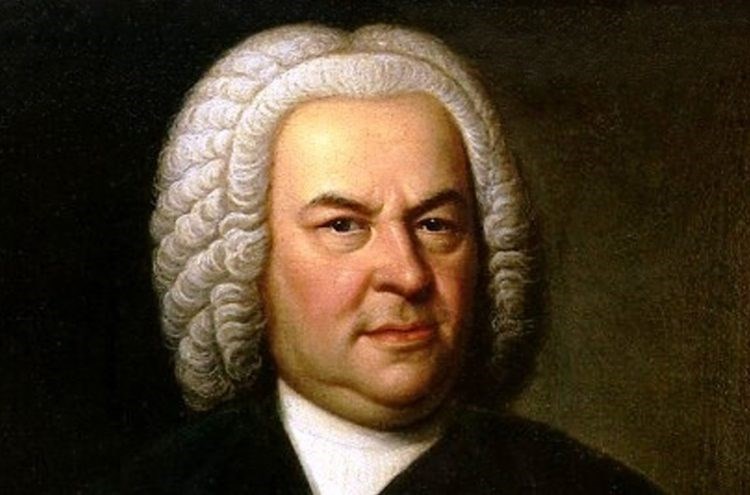

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

JS Bach has been called 'the supreme arbiter and law-giver of music'. He is to music what Leonardo da Vinci is to art and Shakespeare is to literature, one of the supreme creative geniuses of history.

Key recording:

St Matthew Passion

Julian Prégardien (Evangelist), Stéphane Degout (Christus); Pygmalion / Raphaël Pichon (Recording of the Month, April 2022) Read the review

Explore JS Bach:

The 10 best Bach works: a beginner's list – Here are a selection of works by Bach that are essential listening; and once bitten the Bach Bug will take you on a journey of almost limitless reward Presents JS Bach.

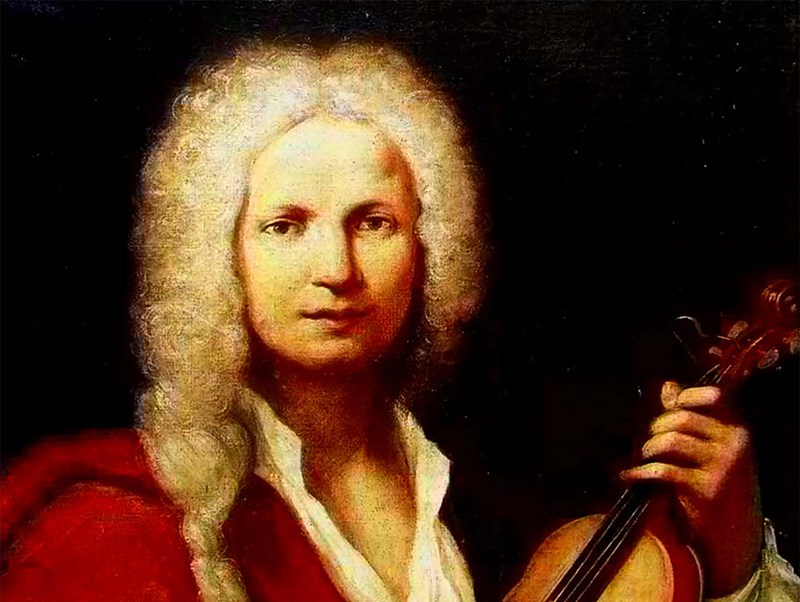

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

With Antonio Vivaldi, Italian Baroque music reached its zenith. The prosperous, cultivated world of contemporary Venice shines through all his works, composed with innate craftsmanship.

Key recording:

The Four Seasons

Rachel Podger vn Brecon Baroque (Editor's Choice, May 2018; shortlisted for the 2018 Gramophone Concerto Award) Read the review

Explore Vivaldi:

Top 10 Vivaldi recordings – Ten of the best Vivaldi recordings, including Gramophone Award-winners and Editor's Choice albums

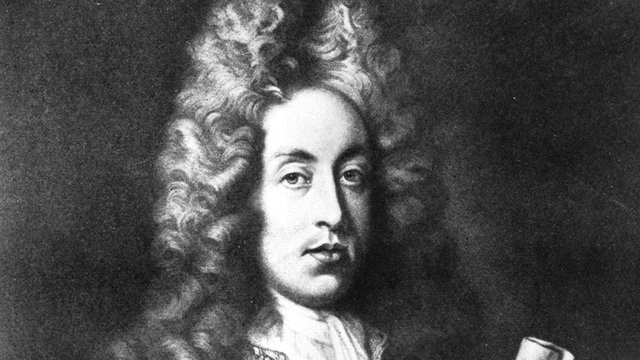

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Handel is one of the giants of musical history. His is happy, confident, melodic music imbued with the grace of the Italian vocal school, an easy fluency in German contrapuntal writing and the English choral tradition inherited from Purcell.

Key recording:

Messiah

Soloists; Dunedin Consort and Players / John Butt (winner of Gramophone's 2007 Baroque Vocal Award) Read the review

Explore Handel:

The Mysteries, Myths, and Truths about Mr Handel – David Vickers takes an in-depth look at the composer, his life, and works.

Henry Purcell (1659-95)

Many regard Henry Purcell as the greatest English composer of all time. Among his most influential works are the opera Dido and Aeneas and the semi-operas The Fairy Queen and King Arthur.

Key recording:

The Fairy Queen

Lucy Crowe, Claire Debono, Anna Devin; Glyndebourne Chorus and Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment / William Christie (DVD of the Month, October 2010; 2010 Gramophone Award for DVD Performance) Read the review

Explore Purcell:

How we made England, my England: 'They actually built a sort-of London for me to burn down. What heaven!' – Tony Palmer reflects on the making of his acclaimed 1995 film on Purcell.

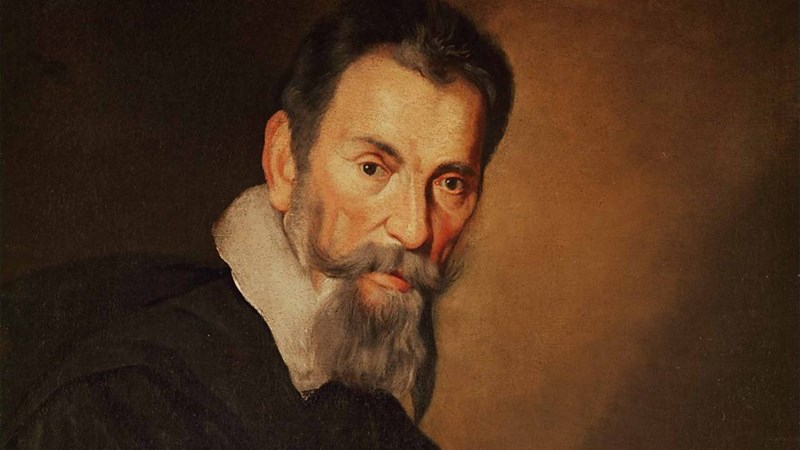

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

Claudio Monteverdi, a composer who bridged the Renaissance period and the Baroque, can be justly considered one of the most powerful figures in the history of music. Among his most notable works are the operas Orfeo and L’incoronazione di Poppea.

Key recording:

Vespers

Taverner Consort / Andrew Parrott (The Top Choice in our Gramophone Collection Article in June 2010) Read the review

Explore Monteverdi:

Monteverdi's Combattimento: which recording is best? In his search for the ultimate recording, Lindsay Kemp finds surprisingly consistent treatment of Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda

Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672)

Heinrich Schütz was the greatest German composer of the 17th century and the first of international stature.

Key recording:

Musicalische Exequien

Vox Luminis / Lionel Meunier (Gramophone's Recording of the Year 2012) Read the review

Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757)

Domenico Scarlatti produced the vast body of instrumental music for which he’s best known, and in particular the keyboard sonatas. These works extended the genre immeasurably, introducing a virtuosity and brilliance that broke new ground.

Key recording:

Sonatas

Yevgeny Sudbin pf (Recording of the Month, April 2016; shortlisted for the 2016 Gramophone Instrumental Award) Read the review

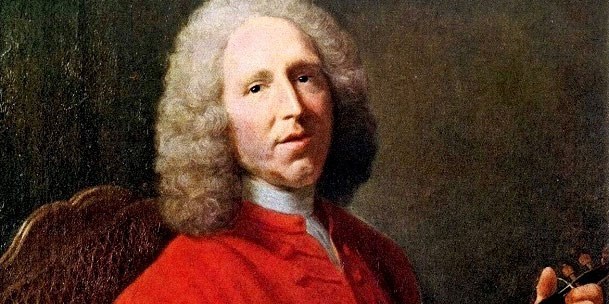

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

Though he was no judge of librettos, Jean-Philippe Rameau raised the musical side of opera to a new level and in his ballets introduced many novel descriptive effects – the French loved these – such as the earthquake in Les Indes galantes.

Key recording:

Overtures

Les Talens Lyriques / Christophe Rousset (winner of the 1998 Gramophone Baroque Non-Vocal Award) Read the review

Explore Rameau:

Top 10 Rameau recordings – David Vickers recommends 10 of the Rameau’s works and their best recordings

Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713)

Arcangelo Corelli was the main founder of modern orchestral playing and the composer who fashioned two new musical forms, the Baroque trio and solo sonata, and the concerto grosso.

Key recording:

Complete Concerti Grossi

Amandine Beyer vn Gli Incogniti (Editor's Choice, February 2014; shortlisted for Gramophone's 2014 Baroque Instrumental Award) Read the review

Explore Corelli:

Top 10 Corelli recordings – Corelli's music continues to inspire musicians and listeners more than 300 years after his death. Here are some of the finest recordings.

Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767)

Georg Philipp Telemann was probably the most prolific composer in musical history. He wrote almost as much as Bach and Handel put together (and each of them wrote a perplexing amount) including 600 French overtures or orchestral suites, 200 concertos, 40 operas and more than 1000 pieces of church music.

Key recording:

Concertos & Cantata Ihr Völker Hört

Clare Wilkinson mez Florilegium (Editor's Choice, September 2016; shortlisted for Gramophone's 2017 Baroque Instrumental Award) Read the review

Friday, April 18, 2025

by Georg Predota

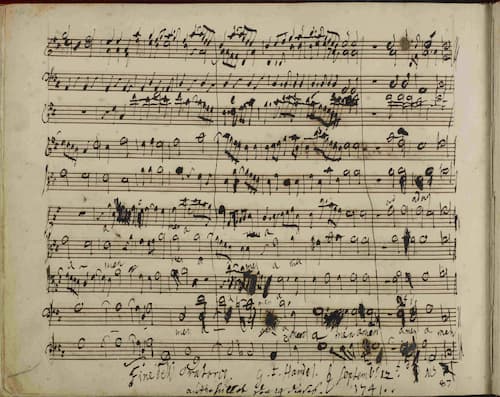

From Germany to Messiah

The German-born English composer George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) is widely regarded as one of the greatest musical masters of his era. Indeed, his extraordinary talent and relentless dedication significantly shaped the landscape of classical music during the Baroque era.

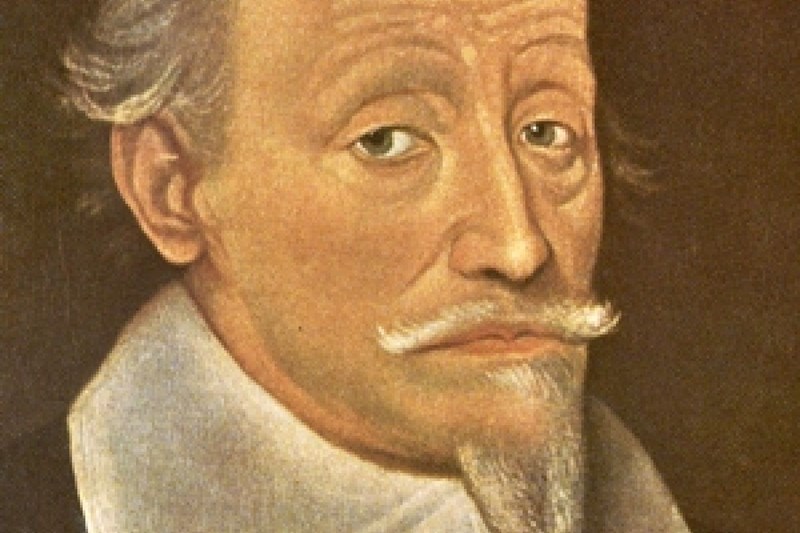

Portrait of George Frideric Handel by Thomas Hudson, 1756

He began his musical journey in Halle, Germany, and honed his skills in Italy before settling in England. Renowned for his operas, oratorios, and instrumental works, Handel masterfully blended German, Italian, French, and English musical traditions into a distinctive and influential style.

Handel showcased his genius for dramatic storytelling and musical innovation throughout, and while his posthumous fame largely rested on a few orchestral works and the oratorio Messiah, Handel excelled in every musical genre of his time.

To commemorate his passing on 14 April 1759 at the age of 74, we decided to celebrate his legacy as one of history’s most towering musical figures.

Halle and Hamburg

George Frideric Handel

Georg Händel was born to a barber-surgeon and his wife Dorothea Taust on 23 February 1685. His father wanted him to take up a legal career, but the boy secretly practiced and received musical training from Friedrich Zachow. When he was not quite 12, his father died and left him with family responsibilities. He briefly enrolled at the University of Halle in 1702 before becoming organist at the Domkirche. He also visited Berlin, where he first encountered opera and the composer Giovanni Bononcini. Inspired, he left Halle for Hamburg in 1703.

Handel joined the city’s independent opera house as a violinist and harpsichordist in 1703, working under Reinhard Keiser’s influence. He befriended Johann Mattheson, with whom he fought a brief duel in 1704, and he began composing when Keiser’s absence created opportunities. His first opera, Almira of 1705, was a success, followed by the less successful Nero. In the event, Handel absorbed Keiser’s eclectic style of blending German, French, and Italian elements, which decisively shaped his future operatic works.

Italy

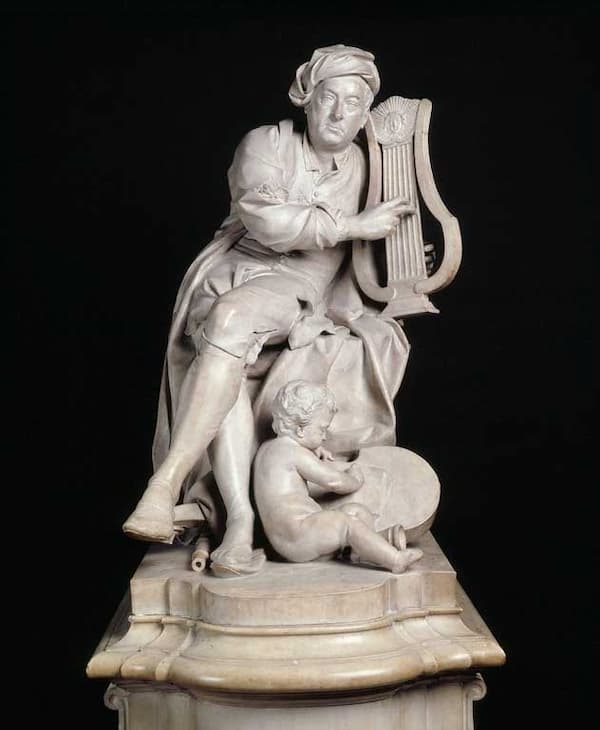

Marble statue of Handel, 1738

While in Hamburg, Handel met visiting musicians who introduced him to Italian music and encouraged him to travel to Italy. Visiting Florence and Venice, Handel arrived in Rome by early 1707 and honed his craft under the influence of composers such as Arcangelo Corelli and Alessandro Scarlatti. His talent quickly earned him the favour of both ecclesiastical and secular princes, and he composed his first opera, Rodrigo, in 1707.

His opera Agrippina, of 1709 triumphed in Venice and solidified his fame with its brilliant arias and dramatic flair. Always the diplomat, Handel navigated elite circles without compromising his independence, and his Italian interlude fuelled his ambition and equipped him with the tools to revolutionise music across Europe. A scholar writes, “Handel’s Italian experience refined his style, blending elegance and dramatic skill, and setting the stage for his later successes.”

Towards London

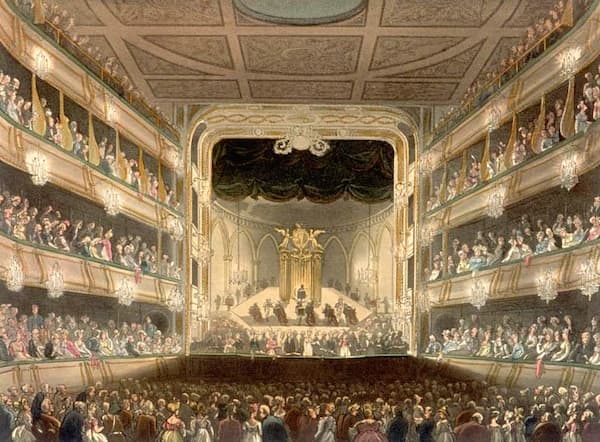

Covent Garden Theatre

Searching for new opportunities, Handel travelled north and arrived in Hanover in 1710, where he was appointed Kappellmeister at the electoral court. He certainly delighted the Electress Sophia and the later King George II with his harpsichord skills. Since his appointment allowed for travel, Handel first arrived in Düsseldorf, and by autumn 1710, he had made his way to London.

Italian opera had taken London by storm, while all-sung English opera faltered as Italian works and singers, particularly castratos became all the rage. The Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket became London’s opera hub, and Handel joined an all-Italian opera company. Rinaldo, his first opera tailored for London, premiered on 24 February 1711. The opera was an immediate success, with contemporary audiences praising “the charms of the music and the splendours of the spectacle.

Cannons

In the summer of 1717, Handel started to work for James Brydges, Earl of Carnarvon, later the Duke of Chandos, at his new mansion, Cannons. During a short but productive period, he composed 11 anthems that, according to scholars, “were unique in English church music.” Significantly, Cannons also saw the completion of the first English oratorio. Esther adapted a biblical drama and reused music from an earlier score.

The Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music was founded in February 1719 during Handel’s residence at Cannons. The primary aim was to secure a constant supply of opera seria, with Handel appointed to engage soloists and to initially provide libretti and some arrangements. Handel’s first season at the RAM was a huge success. By staging Rinaldo, Teseo, Amadigi, and Radamisto, he had quickly reached the commanding position he sought.

In fact, Handel considered the aria “Ombra cara” from Radamisto his finest melody ever. And he was closely involved in general administration and the engagement of singers, made decisions on scenery and staging, and rehearsed the orchestra and the singers. The directorate of the Academy, however, did not want to back Handel exclusively, and their choice of resident composer fell to Giovanni Bononcini, who arrived in London in the autumn of 1720.

Operatic Seconds and Covent Garden

Carriera: Portrait of Faustina Bordoni Hasse (1730s) (Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca’ Rezzonico, Venice)

Over time, Bononcini’s position gradually weakened, and Handel’s influence boosted. The 1723/24 season saw a resounding triumph of Giulio Cesare, and the masterworks Tamerlano (1724) and Rodelinda (1725) marked the Academy’s artistic peak. However, the arrival of soprano Faustina Bordoni in 1726, rivalling Francesca Cuzzoni, created an atmosphere of animosity, and the RAM collapsed at the end of the 1728/29 season.

Handel was undeterred and quickly started a “Second Academy of Music.” He continued to travel to Italy to engage new singers, and he composed several more operas at home. With the rise of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, Handel also came under attack for being a foreigner. In all, Handel composed about 30 operas for the Royal Academy. Still, when a new theatre at Covent Garden opened in 1732, he shifted operations to the new location for two nights a week.

Oratorio

Francesca Cuzzoni

Handel faced shifting public tastes and financial difficulties in London during the 1730s, as Italian opera seria began to lose favour with audiences. This prompted him to pivot toward a new medium, the English oratorio. Combining his operatic flair with a focus on sacred or dramatic narratives, Handel adapted to the cultural and religious sensibilities of his English audience, who preferred works in their native language and were wary of theatrical excess in religious contexts.

His oratorios, a genre he practically invented, were performed in concert settings without staging or costumes, making them more accessible and cost-effective while still delivering emotional depth and musical grandeur. The rise of the oratorio became a cultural phenomenon, and it revitalised his career. In fact, Handel’s oratorios bridged the gap between sacred music and public entertainment, and thus cemented his legacy as a transformative figure in Western music.

Final Musical Thoughts

Handel: Messiah – Part III: Amen

Handel continued to refine and expand the oratorio form, producing some of his most enduring and sophisticated works despite facing significant personal and health challenges. After the triumph of Messiah in 1742, Handel’s late oratorios, such as Samson (1743), Belshazzar (1745), Judas Maccabaeus (1747), and Jephtha (1752), showcased his mastery of dramatic storytelling and musical innovation. Although his eyesight began to fail, his creative output remained remarkably robust, driven by his unrelenting passion and adaptability.

His final years were marked by both physical decline and an enduring public presence. After undergoing unsuccessful eye surgeries, he increasingly relied on assistants to notate his compositions, yet he continued to perform, often improvising at the organ during oratorio performances to the delight of the audience. Just days before his death on 14 April 1759, he attended a performance of Messiah at Covent Garden.

Personality, Style and Legacy

As contemporaries report, Handel was a “large, portly man with a sauntering gait and a mix of irascibility, humour, and good-heartedness.” Honest and reliable in financial dealings, he balanced artistic ideals with the needs of individual singers, adapting compositions while showing mixed attitudes toward fellow composers. And a scholar writes, “socially reserved, he enjoyed a private circle, supported charities, and, despite coarse habits like swearing and overeating, was cherished as a genius until retreating into privacy in later years.”

Handel’s music is characterised by its dramatic intensity, melodic richness, and a masterful blend of emotional depth and structural clarity. It displays a remarkable adaptability, consolidating the characteristics of the leading European styles of his day. His works often balance intricate polyphony with straightforward, singable melodies, making them appealing to both sophisticated listeners and broader audiences. Across all genres, Handel’s music is defined by its accessibility, emotional resonance, and enduring versatility.

Handel’s legacy endures, with his contributions influencing generations of composers and performers. Works like Messiah remain cultural touchstones, performed worldwide and cherished for their universal appeal and spiritual depth. Handel’s ability to blend technical brilliance with profound emotion ensures his continued iconic status, equally eliciting scholarly advocacy and the enthusiasm of practical musicians around the world.

Saturday, September 21, 2024

Violence Against Men: The Age of the Castrato

by Georg Predota , Interlude

Fairy tales normally start with “Once upon a Time,” and generally end with “and they lived happily ever after.” But some of the supposed musical fairy tales I’ve been reading about are not nice stories at all. I am talking about countless young boys who underwent castration for musical purposes. What a ghastly convention practiced almost exclusively in Italy throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Historians tell us, “the taste for castrato voices arose mainly because in large parts of Italy, including the Vatican, women’s voices were not allowed in church.” Since puberty turned choirboys into males and falsettists were considered unsatisfying, the horrid practice began. In a disgusting game of twisting your arm, princely states, leading churches or singing companies approached the parents of a boy who was considered the most talented singer in his church choir. Boys were generally recruited before the age of twelve and from the poorest areas and the poorest families. Since the leading castratos were among the most famous and most highly paid musicians in Europe, it supposedly offered great financial security for many families facing starvation.

Alessandro Moreschi, 1900

Surgeons used minimal anaesthesia while performing the “operation.” On occasion, “a certain quantity of opium was given to persons designed for castration, whom they cut while there were in their dead sleep…but it was observed that most of those who had been cut after this manner died.” If the boy happened to survive the operation, the lack of testosterone made his thoracic cavity developed greatly, “while the larynx and the vocal cords developed much more slowly.” Combined with intensive training, castrati often had unrivalled lungpower and breath capacity. Singing through small and child-sized vocal chords, their voices were extraordinarily flexible and quite different from the equivalent adult female voice. We only have a single sound document to give us a taste of what a castrato voice actually sounded like. Alessandro Moreschi (1858-1922), the last Sistine castrato, was known as “The Angel of Rome” at the beginning of his career. When he made his recordings in 1902 and 1904, he was clearly past his prime, but we still get a fascinating glimpse into the sound world of the castrato.

Subjecting boys to the “operation” produced a host of different outcomes. A leading scholar writes, “There were high-sopranos, mezzos, and altos, strident voices and sweet ones, loud and mellow voices, more and less flexible throats, very tall men and very short, well and ill-proportioned castrati.” The vast majority of castrati were mediocre or bad singers and became low-level performers traveling between small towns. A very small number, however, reached unprecedented fame, and their abilities had great influence on the development of both oratorio and opera. Let’s go ahead and meet some of the most famous castrati and the repertory they inspired, starting with Giovanni Grossi, nicknamed “Siface” (1653–1697). That particular nickname originated from his stellar performance of “Syphax” in Cavalli’s Scipione affricano in Rome in 1671. He was in the service of the Duke of Modena, and he sang at the opening of the “Teatro Grimani” in Venice. It is said, that his fame even attracted the attention of Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome.

Giovanni Grossi, nicknamed “Siface”

Siface traveled to Paris and London, and a contemporary witness reports. “I heard the famous singer, the Eunuch Cifacca, esteemed the best in Europe and indeed his holding out and delicateness in extending and loosing a note with that incomparable softness, and sweetness was admirable: For the rest, I found him a mere wanton, an effeminate child; very coy and proudly conceited.” His beautiful voice was sadly contrasted by his bad temper, arrogant behaviour, and volatile temperament. Like Alessandro Stradella, “Siface” was murdered for an indiscreet affair, about which he foolishly boasted. When Siface traveled between Ferrara and Bologna, where he was engaged to sing, he was killed by musket fire at the hands of assassins hired by the woman’s family. The murder created a great scandal, and the Duke of Modena made sure the guilty party was held accountable. Siface’s voice was long remembered; in 1741, he was still “famous beyond any, for the most singular beauty of his voice.”

Nicolo Grimaldi, nicknamed “Nicolini”

The famed alto castrato Nicolo Grimaldi, nicknamed “Nicolini” (1673–1732) was considered the leading male singer of his age. The critic and musicologist Charles Burney described him as “a great singer and still greater actor.” Joseph Addison called him “the greatest performer in dramatic music that is now living or that perhaps ever appeared on a stage.” Born in Naples, Nicolini sang in Naples Cathedral and the royal chapel from 1690. He frequently appeared in opera and, during his early career, was primarily associated with Alessandro Scarlatti. In fact, he sang in the premières of Scarlatti’s La caduta de’ Decemviri (1697), Il prigioniero fortunato (1698), Arminio, L’amor generoso and Scipione nelle Spagne (1714), Tigrane (1715) and Cambise (1719). He took part in thirty-six productions in Naples and thirty-four in Venice, and countless composers created roles for him.

When Nicolini went to London in 1708, he became partly responsible for the increasing popularity of Italian opera in London. He made his England début at the Queen’s Theatre in Haym’s arrangement of Scarlatti’s Pirro e Demetrio. That performance was a huge success, and he signed a three-year contract with Owen Swiney. He sang in all the operas during that period and also sang the title role in the first performance of Handel’s Rinaldo. Until the age of 50, Nicolini “followed the pattern typical for star castrati.” Instead of retiring, however, Nicolini began to take on characters whose age approximated his own. Between 1727 and 1731, all new roles specifically written for him were typical tenor roles. These roles helped Nicolini “to conceal his vocal liabilities—shortness of breath, diminished range and sound quality—as they lent themselves to situations in which characters express passions such as vengefulness, disdain, imperiousness, reproachfulness or remorse.” In 1731, Nicolini was engaged to sing in Pergolesi’s first opera Salustia, but he died during rehearsals.

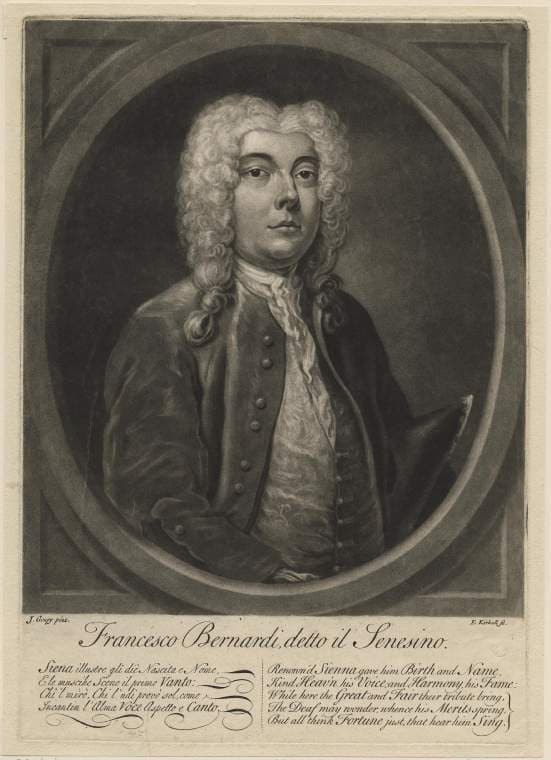

Francesco Bernardi, nicknamed “Senesino”

Francesco Bernardi (1686–1758) was born in Siena, and his nickname “Senesino” was derived from his birthplace. He became one of the most acclaimed castrato singers of his day, and his vocal ability was described in some detail. “He had a powerful, clear, equal and sweet contralto voice, with a perfect intonation and an excellent shake. His manner of singing was masterly, and his elocution unrivalled. Though he never loaded Adagios with too many ornaments, yet he delivered the original and essential notes with the utmost refinement. He sang Allegros with great fire and marked rapid divisions from the chest in an articulate and pleasing manner. His countenance was well adapted to the stage, and his action was natural and noble. To these qualities, he joined a majestic figure.” Senesino initially toured a huge number of Italian theatres and was engaged for Dresden in 1717. He commanded a huge salary but was fired for insubordination in 1720. Apparently, he refused to sing one of the arias from Heinichen’s Flavio Crispo, and tore up the part.

George Frideric Handel, who had been scouting Senesino, brought him to London and engaged him for his company. Senesino joined the Royal Academy of Music for its second season in September 1720. He made his début at the King’s Theatre on 19 November in Giovanni Bononcini’s Astarto and remained a member of the company until June 1728. Senesino sang in all 32 operas produced during this period, and that included seventeen leading roles composed by Handel. Senesino was a superstar, and described as “beyond Nicolini both in person and voice… and beyond all criticism.” The relationship between Handel and Senesino was frequently stormy, as “one was perfectly refractory; the other was equally outrageous.” By all accounts, Senesino’s character was “marred by touchiness, insolence and an excess of professional vanity.” It is reported that he insulted Anastasia Robinson at a public rehearsal in 1724, “for which Lord Peterborough publicly and violently caned him behind the scenes.” Senesino’s tantrums and intrigues were largely responsible for the split with Handel in 1733. In the event, his musical qualifications were superb. He was renowned for “brilliant and taxing coloratura in heroic arias and expressive mezza voce in slow pieces.” Apparently, he had no equal in the pronunciation of recitative, and he “was unsurpassed in accompanied recitatives.

Giacinto Fontana, nicknamed “Farfallino”

Giacinto Fontana (1692–1739), nicknamed “Farfallino,” was primarily active in Rome between 1712 and 1736. Apparently, he specialized in singing soprano female roles, and was said to have had a high-pitched and small boyish voice. Rather feminine in appearance, he is known to have portrayed an occasional pregnant primadonna. It was his graceful stage appearance that probably earned him his nickname “Little Butterfly.” Graceful stage appearance aside, he seemed to have had a somewhat violent temper, as he almost fought a duel with another musician behind the scenes. “The music he sang does not suggest extraordinary technical abilities,” but he nevertheless created roles in operas by Bononcini, Scarlatti, Vivaldi, Vinci and the later works of Francesco Gasparini.

Saturday, July 27, 2024

The Evolution of Handel's Music (From 14 to 66 Years Old)

/ pianomusicbros

► Twitter:

/ pianomusicbros

► Twitter:  / pianomusicbros

* Affiliate Link

Enjoy this video showing the evolution of Handel's music from age 14 to 66 years old.

0:00 14 Years Old: Trio Sonata in G minor, HWV 387, 1699

0:32 19 Years Old: Oboe Concerto in G minor, HWV 287, I. Grave, 1704

1:06 20 Years Old: Gavotte in G major, HWV 491, 1705

1:44 22 Years Old: Rodrigo, HWV 5, Act III, Scene VII, Allorché sorge astro lucente, 1707

2:15 26 Years Old: Rinaldo, HWV 7, Act II, Scene IV, Lascia ch'io Pianga, 1711

2:42 28 Years Old: Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne, HWV 74, I. Eternal Source of Light Divine, 1713

3:16 31 Years Old: Fugue in G minor, HWV 605, 1716

3:45 35 Years Old: Suite in F-sharp minor, HWV 431, IV. Gigue, 1720

4:23 39 Years Old: Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17, Act III, Scene III, Piangerò la sorte mia, 1724

5:09 40 Years Old: Rodelinda, regina de' Longobardi, HWV 19, Act I, Scene I, Hò perduto il caro sposo, 1725

5:53 45 Years Old: Violin Sonata in G minor, HWV 368, I. Andante, 1730

6:25 48 Years Old: Suite in D minor, HWV 437, III. Sarabande, 1733

6:53 50 Years Old: Alcina, HWV 34, Act II, Scene XII, Verdi prati, selve amene, 1735

7:21 51 Years Old: Organ Concerto in B-flat major, HWV 294, I. Andante allegro, 1736

7:41 52 Years Old: Serse, HWV 40, Act I, Scene I, Ombra mai fù, 1737

8:24 55 Years Old: L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, HWV 55, Part 3, As steals the morn, 1740

9:07 56 Years Old: Messiah, HWV 56, Part II, Scene VII, 44. Hallelujah, 1741

9:37 57 Years Old: Samson, HWV 57, Act I, Total Eclipse, 1742

10:06 61 Years Old: Judas Maccabaeus, HWV 63, Act III, XXXV. See, the Conqu'ring Hero Comes!, 1746

10:40 63 Years Old: Solomon, HWV 67, Act III, Sinfonia II. Arrival of the Queen of Sheba, 1748

11:18 66 Years Old: Jephtha, HWV 70, Part 3, 53. Waft her, angels, 1751

/ pianomusicbros

* Affiliate Link

Enjoy this video showing the evolution of Handel's music from age 14 to 66 years old.

0:00 14 Years Old: Trio Sonata in G minor, HWV 387, 1699

0:32 19 Years Old: Oboe Concerto in G minor, HWV 287, I. Grave, 1704

1:06 20 Years Old: Gavotte in G major, HWV 491, 1705

1:44 22 Years Old: Rodrigo, HWV 5, Act III, Scene VII, Allorché sorge astro lucente, 1707

2:15 26 Years Old: Rinaldo, HWV 7, Act II, Scene IV, Lascia ch'io Pianga, 1711

2:42 28 Years Old: Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne, HWV 74, I. Eternal Source of Light Divine, 1713

3:16 31 Years Old: Fugue in G minor, HWV 605, 1716

3:45 35 Years Old: Suite in F-sharp minor, HWV 431, IV. Gigue, 1720

4:23 39 Years Old: Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17, Act III, Scene III, Piangerò la sorte mia, 1724

5:09 40 Years Old: Rodelinda, regina de' Longobardi, HWV 19, Act I, Scene I, Hò perduto il caro sposo, 1725

5:53 45 Years Old: Violin Sonata in G minor, HWV 368, I. Andante, 1730

6:25 48 Years Old: Suite in D minor, HWV 437, III. Sarabande, 1733

6:53 50 Years Old: Alcina, HWV 34, Act II, Scene XII, Verdi prati, selve amene, 1735

7:21 51 Years Old: Organ Concerto in B-flat major, HWV 294, I. Andante allegro, 1736

7:41 52 Years Old: Serse, HWV 40, Act I, Scene I, Ombra mai fù, 1737

8:24 55 Years Old: L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, HWV 55, Part 3, As steals the morn, 1740

9:07 56 Years Old: Messiah, HWV 56, Part II, Scene VII, 44. Hallelujah, 1741

9:37 57 Years Old: Samson, HWV 57, Act I, Total Eclipse, 1742

10:06 61 Years Old: Judas Maccabaeus, HWV 63, Act III, XXXV. See, the Conqu'ring Hero Comes!, 1746

10:40 63 Years Old: Solomon, HWV 67, Act III, Sinfonia II. Arrival of the Queen of Sheba, 1748

11:18 66 Years Old: Jephtha, HWV 70, Part 3, 53. Waft her, angels, 1751

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)