© Perennial Music and Arts

It is commonly believed that creating with no constraints is what is most fruitful; what the artist seeks; ultimate freedom in his creative choices. Contrary to this belief, what is often more productive — and tends to breed creativity and results — is to impose oneself some limits and constraints; rules and borders to define the parameters of creation. One way this takes place is through musical forms.

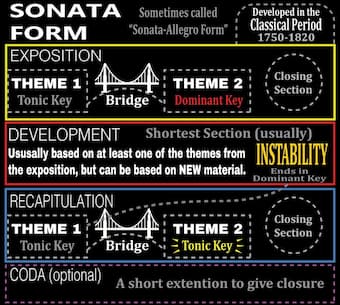

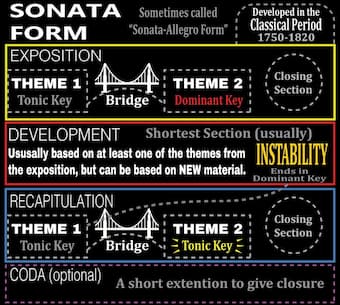

Musical forms are very useful tools in order for the composer to create and for the listener to find guidance and set the expectations of the music. A form can broadly be defined as the generic structure of a musical composition — or performance — and there are many different forms, which have been created and have evolved over the years.

Some works have benefited from the absence of form, such as the prelude, the impromptu or the fantasia, yet in their inner and microscopic structure one can often find some sort of coherent structure.

In other words, a form is a canvas for the musician, a structure or a blueprint in order for the composer to organise his musical ideas, find introduction, direction, development, and resolution.

Most musical forms were set during the baroque period and were the result of functional purposes; through dance suites — which were the main forms of entertainment in the 18th century — religious services —such as the oratorio, cantata or the mass — and later more musical centred forms such as the sonata or the partita. Vivaldi, Bach, Handel all used this format to develop their music.

During the classical period, additional forms emerged and took the centre of the stage — particularly the concerto, the symphony and the quartet — and provided a canvas for the works of Haydn and Mozart; it is through the romantic period that their development reached its pinnacle, eventually reaching its peak during the modern period after which it started its implosion; today they are merely a nostalgia.

© external-preview.redd.it

Today forms are still present, but well coated and hidden, and it is the listener’s role to find out which it is. When used in an obvious manner, it is a way for the composer to hint at something specific; a period, a reference, a composer or a musical intention – Adès’ Mazurkas spring to mind. Through the way classical music has evolved, it is no longer a case of function — the last music which really intends to carry a function is nowadays reserved to screen or daily life activity — but rather a form of entertainment, and therefore its necessity has somehow disappeared.

Interestingly enough, these forms seem to have been maintained in other genres of music; in pop for instance, it is quite observable — and at times critical — how these forms are used over and over, in a magic recipe on the quest of commercial success. It is quite understandable; whether with 18th century classical composers or current pop artists, one of the aims for the living musician, is for his music to be popular and successful, as well as fruitful. It is also under a strong business productive pressure, and forms in this instance are quite essential in order to reach success.

In any form of art, if the artist wishes to learn the rules, he undoubtedly rushes to break them and explore his creativity — and grow away from what seems to be at times, rigorous structures. One can only think of Picasso‘s career to illustrate this sentence. It is no surprise that progressively the forms which have been at the basis of all Western classical music would disappear. What remains to wonder is if the disappearance of these structures has in its turn created new forms of their own, which will eventually become their own standardised musical forms.