It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, May 3, 2024

Rhythm Of The Rain - THE CASCADES - With lyrics

On My Music Desk…… Claude Debussy – La cathédrale engloutie (The Sunken Cathedral)

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

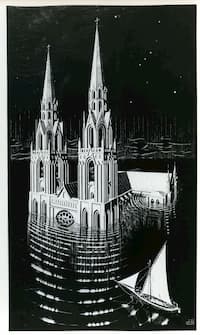

La Cathedrale engloutie – Escher

(Brigham Young University Museum of Art)

In this piece, composed in 1910 and included in Book 1 of the Preludes for piano, Debussy demonstrates his mastery of not only the piano miniature form in creating such a potent narrative in just a few pages of music, but also his deep appreciation of the instrument’s sonic palette. His music is often compared to the paintings of Claude Monet, in which ‘impressions’ of a scene or landscape are rendered through a limited palette and short brush strokes applied over a pale-coloured ground or ‘base’, which create remarkable luminosity, texture and colour blends. This has led to a misconception in the interpretation and performance of Debussy’s music in which some performers “blur” the sounds, often with over-use of the sustaining pedal.

In fact, Debussy disliked the term “impressionist”, and any temptation to employ “impressionistic” pedalling is misguided. Monet and other Impressionist painters did not blend their colours but in fact separated them – it is this separation which creates the remarkable effects of light, when viewing their paintings at a distance. Similarly, when playing and, more specifically, pedalling Debussy’s piano music, “separation” or definition of individual timbres is required; if anything, his music demands an almost Mozartian clarity.

Le Mont-Saint-Michel

Debussy did not give this prelude, nor the others in the two books, a title on the opening page. Instead each one was assigned a number, with the title placed at the end of the piece, allowing pianists to form their own individual, intuitive impressions of the music before the composer reveals his intent.

Like Monet’s pale ground on which he built his paintings, Debussy’s employs a “ground” in the opening section of the music in the form of whole-bar chords in open fifths. Over this, another chordal figure, also in open fourths and fifths, which recalls the harmonies and timbres of gamelan music, which Debussy encountered at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889, and also the simple harmonies of early Medieval liturgical music. The opening direction Profondément calme sets the scene, while the secondary direction Dans une brume doucement sonore (“in a soft mist of sound”) should not be taken as an excuse to depress the pedal fully. The arc of the phrases is perhaps suggestive of the cathedral’s gradual emergence from the sea, and indeed the overall structure of the entire piece suggests an arch form.

A key change into B Major signals a shift in the narrative. Here the cathedral begins to emerge more distinctly from the mists and waves: this is portrayed through an arpeggiated figure in the bass which evokes the rolling movement of the sea. Chords continue in the right hand: this is the sound of the organ growing louder as the cathedral emerges. By bar 28, the organ is heard in all its grandeur, with dense fortissimo chords in treble and bass. This is the climax of the music and here we can imagine the cathedral fully visible, its organ playing in glorious full volume. The weight and power of the organ is further emphasised by the tolling of a single bell, deep in the bass. At bar 41 the cathedral begins to retreat and by bar 47, the organ is heard distantly as the water subsumes the building, but bursting forth again, momentarily, at bars 59-62.

In the closing section of the piece another rolling figure in the low bass represents the sea while the organ is heard faintly, also in a lower register. One senses its magnificence, even if obscured by the water. Finally, in the final measures, the cathedral’s bells are heard distantly in haunting pianissimo.

In the video below, created by the piano department of the London College of Music, a process known as “hyper production” was used to create a “layered” performance of the piece. The score was divided into separate elements, such as “bells” or “monks’, which then informed the treatment of each element in the recording process to create a more intense and colourful sound when played back through a 3D Audio speaker array (like surround sound). It’s certainly an interesting approach – though the result may not to be everyone’s taste – and I think it is instructive as it clearly highlights and differentiates the individual motifs of the music.

The entire piece is remarkably graphic, with a clarity and layering of contrasting voices and timbres which calls for extremely precise yet highly expressive playing. Managing the climactic episode is an exercise in control to portray the full grandeur of the organ, and the monumentalism of the cathedral itself as it rises from the waves and swell of the ocean.

The Russian Art Song (Romance) Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

by Georg Predota, Interlude

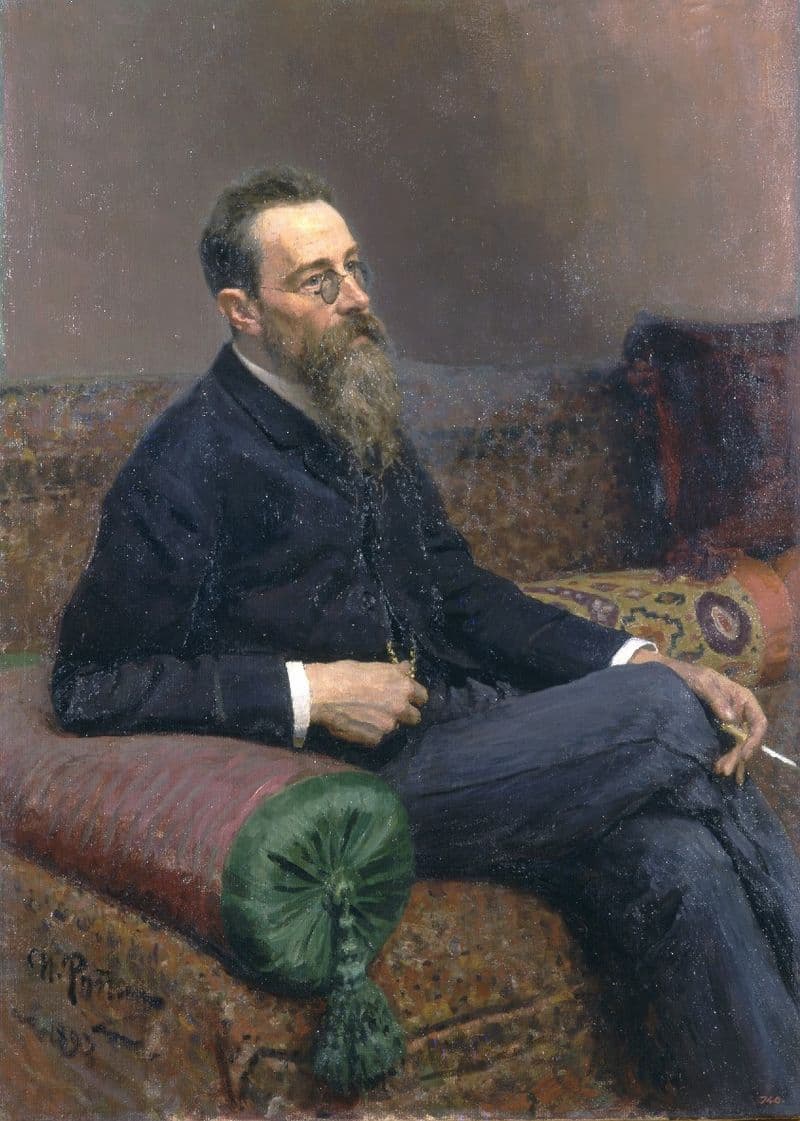

Repin: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Romances gradually evolved from the pastime of the rich and famous into an acknowledged musical genre. As Rimsky-Korsakov wrote in 1897, “I think that in their requests for melodiousness, sing- ability and expansiveness, singers and the public at large are right… short melodies, fragmentation, music departing from harmonies, and demand for dissonances – are things in themselves undesirable… There was a time (I remember it) in the sixties when the majority of Chopin’s melodies were considered weak and cheap music… But nevertheless, pure melody, deriving from Mozart, through Chopin and Glinka is alive up till now, and has to remain alive, for without it the fate of music is decadence.”

On Georgian hills lies night’s darkness;

Aragvi roars before me.

I feel sorrowful and at ease; my sadness is light;

My sadness is full of you,

You, only you…

My gloom is not disturbed or tortured by anything,

And my heart again burns and beats faster because

It cannot renounce love.

Mily Balakirev

In his autobiography, Rimsky-Korsakov claimed that his first song was a setting of a poem by Heinrich Heine in December 1865. While this particular claim can’t be verified, he did compose 22 Romances during his apprenticeship with Mily Balakirev. Initially, Rimsky-Korsakov was harmonizing the Russian folksongs collected by Balakirev. Rimsky-Korsakov remembers, “Balakirev had at that time a large stock of Oriental melodies and dances. He often played them for others, and me in his own most delightful harmonization and arrangements. My acquaintance with Russian and Oriental songs at the time marked the origin of my love for folk music, to which I devoted myself subsequently.” Rimsky-Korsakov’s encounter with oriental melodies and dances immediately transferred into his romance settings.

Enchanted by the rose, a nightingale

Day and night sings above it;

But the rose listens silently…

In that way a poet with his lyre

Sings for a young maiden;

But the dear maiden knows not

To whom he sings and why

His songs are so full of melancholy.

From the very beginning, Rimsky-Korsakov’s romances have an artistry that is foremost a musical one, as he strove to form a symbiotic relation between the poetic statement and a singable design. Inspired by hearing the soprano Ermolenko-Yuzhina at the house of Mikhail Glinka’s sister, Rimsky-Korsakov issued his Four Romances Op. 2, in 1866.

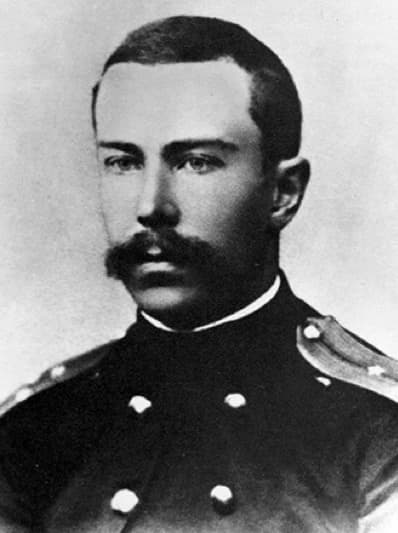

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, 1866

The second song of the set is titled “The Nightingale and the Rose.” Penned by the young Russian poet Aleksei Koltsov in the “Persian style,” the poem is set by Rimsky-Korsakov with a static chordal accompaniment infused with oriental arabesques, with the declamatory vocal line reeling with the agony of the lover’s grief.

Your glance is as radiant as the heavens

With its azure enamel;

Your youthful voice like a kiss

Vibrates and melts away.

Just for the sound of your magical accents,

For your single gaze

I’d gladly give up the hero of the battle –

My Georgian dagger…

The cornerstone of Rimsky-Korsakov’s professional credo was “a scholarly and learned approach to composition technique, diligent attention to all aspects of craft, and the urge to tame musical anarchy and dilettantism.” In his compositional technique, Rimsky-Korsakov was essentially European-trained while at the same time being firmly rooted in the unmistakable Russian music tradition. “He actively pushed the confines in the sphere of harmony, in no small part through the usage of the whole-tone and octatonic scales, which opened up possibilities for a wider harmonic palette and delicious relations between tonalities.”

I bitterly lamented amidst the desert:

“Who from now on will be

As close to my heart as You once were?”

The echo responded: “Alas!”

“How will I live on, sick and morose,

Tormented by ever present sorrow

And many onerous years?”

The echo responded: “Alone!”

“But what should I do? The world is a grave,

Meaningless life is abhorrent to me.

Where is former splendour, pleasure and paradise?”

The echo said: “Dead!”

Apollon Maikov

After having published his Romances Opp. 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8, Rimsky-Korsakov did not return to the genre until the early 1880s. This reawakening coincided with his desire to author a theoretical textbook. As he writes, “When I took over Lyadov’s class in harmony, I grew exceedingly interested in teaching that subject. Tchaikovsky’s system (I followed his textbook in private lessons) did not satisfy me… and I conceived the idea of writing a new textbook on harmony, according to a wholly new system as regards pedagogic methods and sequences of exposition.” For the romance composer, harmony and counterpoint, “providing very many sonorities of great variety and complexity.”

Of what in the quiet night I secretly dream,

Of what in the light of day I think every hour, –

Will remain a mystery to everyone, and even to you, my verse,

You, my flighty friend, my daily consolation,

To you I won’t convey the yearnings of my soul,

Because you might reveal whose voice in the night’s silence,

I hear, whose face appears to me in everything,

Whose eyes shine for me, whose name I

endlessly repeat.

Rimsky-Korsakov once again turned his attention to different matters, and there was an extended interruption in the composition of the romances. In fact, Cesar Cui remarked in 1896, “Rimsky-Korsakov apparently does not have much interest in the genre.” However, during his great Liederjahr of 1897, Rismky-Korsakov composed 47 romances. Yet his approach to vocal style had undergone a noticeable change. The poem for Op. 40, No. 3 “In the Still of Night,” was written by Apollon N. Maykow and carries the subtitle “Elegia.” The music tenderly traces an internal nocturnal dream, with the musical substance entirely derived from the emotional content and diction of the poetry.

Not the wind blowing from on high

Has touched the leaves in the moonlit night –

My soul has been touched by you:

It is aflutter, like the leaves,

It is as sensitive as the lyre’s strings.

The blizzard of life was tearing it apart,

And with the crushing attack,

Whistling and howling, tore the strings,

And covered my soul with icy snow;

But your voice caresses my hearing,

Your touch is as light

As the down flying from the flowers,

Like a breeze of the May night.

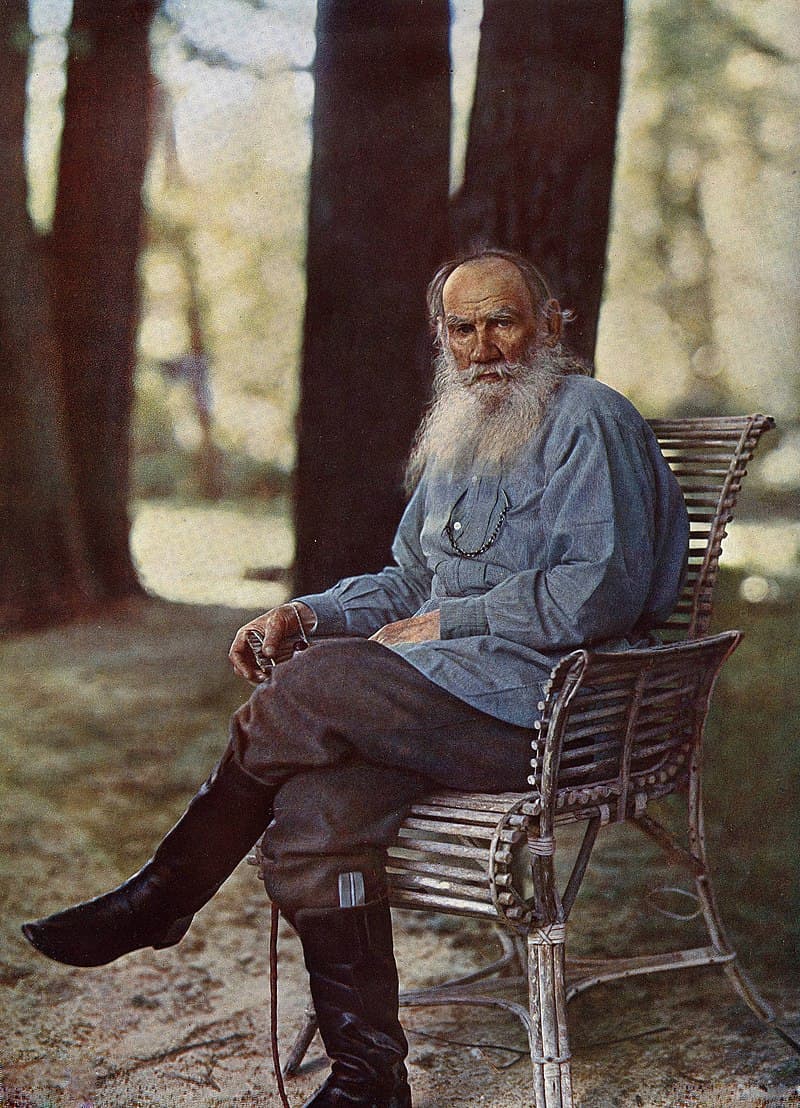

Leo Tolstoy

As Rimsky-Korsakov reports, his method of composition had undergone a significant change. He writes, “I had composed no songs for a long time. Turning to Tolstoy’s poems, I wrote four songs, and the feeling came over me that I was not composing in the same way as I used to. The melody of these songs, following the text, turned out purely vocal with me; that is, it became such at its very birth, with but mere hints of harmony and modulation accompanying in its train. The accompaniment formed and developed after the melody had been composed, whereas formerly, with few exceptions, either the melody was created as if instrumentally, that is, apart from the text, though in harmony with its general purport, or it was stimulated by the harmonic foundation which occasionally preceded the melody.”

I know the reason why by these shores

A mysterious pensive mood seizes the sailors:

A melancholy nymph with flowing tresses,

Half-hidden by rustling reeds,

Sometimes sings a song there

About the silk of her hair,

The azure of her tearful eyes, the pearls of her teeth,

And a heart full of unrequited love.

Passing by in a boat an enchanted sailor

Listening to her song stops rowing;

And, even when she falls silent,

He still imagines for a while the singing above

the waters,

And the nymph in the reeds

With flowing tresses.

Alexander Pushkin

Having found a new method of composition, Rimsky-Korsakov was elated to have discovered, “the true vocal music, and feeling satisfied, too, with my first essays in this direction, I composed song after song to words by Tolstoy, Maykov, Pushkin, and others. In no time at all, I had well-nigh a score of songs already.” Significantly, Rimsky-Korsakov discovered that his new way of composing romances would also lend itself to the writing of operas. As he explains, “I had a feeling that I was entering upon some new period and that I was gaining mastery of the method, which heretofore had been quasi-accidental or exceptional with me.”

Amid a desert, arid and bare,

In soil, flaming with heat,

The Upas tree, like a fearsome guard,

Stands alone in the entire universe.

The nature of the barren steppes

Created it in the day of wrath

And soaked with deadly poison

Its green branches and its roots.

The poison percolates through its bark

Melting from the midday heat,

And congeals by evening

Into a dense translucent resin.

Birds nor beasts roam not near it:

Only a black whirlwind

Occasionally would fly nearby –

And rush away, but already deadly.

And if a wondering cloud would sprinkle

Upon its dense foliage,

From its branches, the toxic rain

Flows down into the sizzling sand.

But a human sent another human

To the Upas tree with a commanding glance;

And he obediently set off on a journey,

Returning by the morning with the poison.

He brought back the deadly resin

And a branch with withered leaves;

The sweat across his pale face

Was flowing in cold streams.

He weakened and laid down

Under a tent upon a trestle-bed,

And the poor slave died

By the feet of an unconquerable sovereign.

Meanwhile the Tsar drenched with that poison

His obedient arrows

And sent around death

To neighbours in foreign lands.

Rimsky-Korsakov later suggested that these romances merely served as preparatory exercises for the operatic compositional spree of his later years. Essentially, he viewed them as studies for finding and perfecting new ideas and methods before implementing them in an operatic context. He also demystified the concept of musical nationalism. “In my opinion,” he writes, “a distinctively Russian music does not exist. Both harmony and melody are pan-European. Russian songs introduce into counterpoint a few new technical devices, but to create a new, unique kind of music, this they cannot do. Russian traits, and national traits in general, are not acquired by writing according to specific rules, but rather by removing from the common language of music those devices which are inappropriate to a Russian style.”

Tormented by spiritual anguish

I dragged myself through a grim desert,

And a six-winged seraphim

Appeared to me at a crossroads;

With his fingers, light as a dream,

He touched my eyes:

They burst open wide, all-seeing,

Like those of a startled eagle.

He touched my ears

And they were filled with clamour and ringing:

I heard the rumbling of the heavens,

The high flight of the angels,

The crawling of the underwater reptilians

And the germinating of the grapevine in the valleys.

He pressed against my lips

And tore out my tongue,

Both exuberant and sly,

And into my frozen lips

The sting of a wise snake

He pushed with his bloody hand.

He cleaved my chest with a sword

And took out my trembling heart,

And thrust into my opened breast

A flaming piece of coal.

I lay in the desert like a corps.

And God’s voice called to me:

“Arise, my prophet, behold and hark,

Submit to my will,

And, traveling across the seas and lands,

Spark people’s hearts with verse.”

Comparable in volume and significance to the romance output of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov’s chamber vocal compositions fully reflect the range of traits and features we find in his larger works. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that he was frequently dubbed the “Singer of the Russian Soul.”

200th Anniversary of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony

by Georg Predota, Interlude

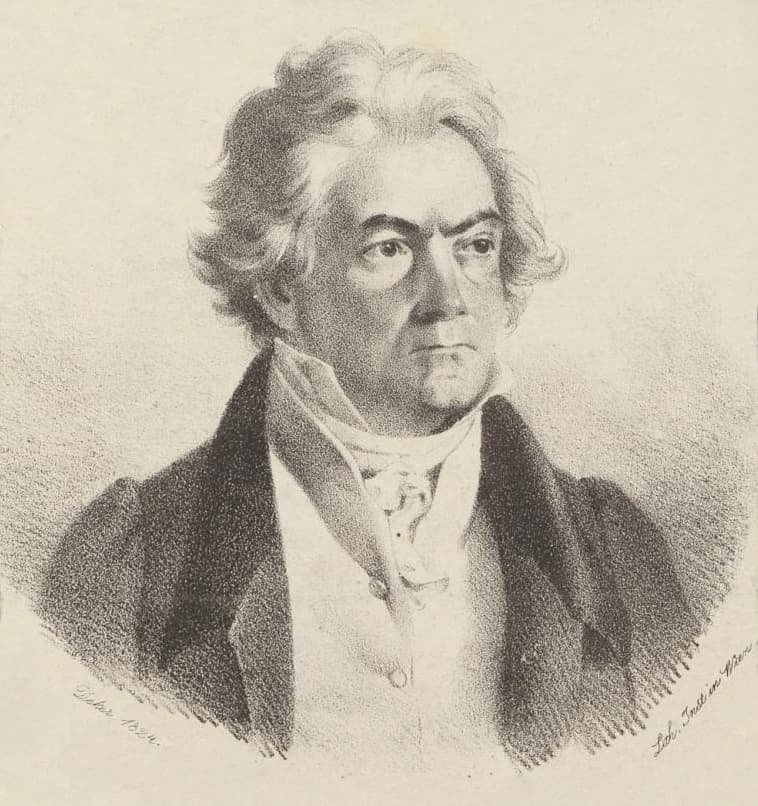

Ludwig van Beethoven in 1824

To commemorate the 200th anniversary of this memorable event, the Beethoven-Haus Bonn has organised an extensive and multi-faceted 10-day anniversary programme. Visitors and enthusiasts, onsite and online, are treated to exhibitions, a book presentation and signing, a conference, various exhibitions, concerts, and livestreams. At the heart of the celebration is the re-creation of the 7 May 1824 concert at the Stadthalle Wuppertal.

7 May 1824

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

In 1824, Beethoven assembled a large orchestra and recruited Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger to sing the soprano and the contralto parts, respectively. According to participating musicians, the 9th Symphony had only two full rehearsals, and was prefaced by the Overture Op. 124 and the Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei from the Missa Solemnis. Unsurprisingly, various stories and anecdotes surrounded this momentous occasion. Beethoven, stone deaf at this time, actually took part in the performance by giving the tempos for each part and turning the pages of his score “as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.”

However, the official conductor Michael Umlauf, had instructed the singers and musicians to ignore all of Beethoven’s instructions. When the concert had ended, Beethoven was still conducting and Caroline Unger is credited with turning Beethoven to face the applauding audience. Beethoven’s underlying conception of music as a mode of self-expression still resonates strongly today, and whether one agrees with, or rejects his compositional approach, after him, nothing in music could ever be the same.

7 May 2024

Martin Haselböck

200 years later, the complete premiere performance will be reconstructed by the Orchester Wiener Adademie, considered one of the leading period-instrument orchestras. Soloist and the WDR Rundfunkchor under the musical direction of Martin Haselböck invite audiences to the 19th-century historical City Hall in Wuppertal to experience the original programme in its original order and its entirety. This promises a unique and rather lengthy listening experience, and one that will undoubtedly provide a new and unique perspective.

As the Director of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn, Malte Boecker explains, “to mark its 200th anniversary, we are presenting the Ninth for the first time in the sound of 1824 again as well as in the probable instrumentation, the line-up and the programmatic arrangement that Beethoven himself had planned.” Researchers and scholars have been able to reconstruct a number of facts regarding the original performance. Apparently, the choir had been positioned in front of the orchestra and not as we have come to expect, behind the instrumental forces. Additional research has suggested a possible instrumentation described by Beethoven, and important new details regarding the musical text.

Romantic Historiography and Meaning

Caroline Unger

According to the organisers of the anniversary concert, “in terms of content and aesthetics, the reconstructed programme shows a variety of relationships and suggests that Beethoven wanted to appeal to the idea of Eternal Peace with the Academies.” By definition, ascribing meaning to a programme and/or a particular work is a slippery subject, as we can interpret Beethoven’s meaning in endless ways. It all depends on our interests as modern reconstructions, while historically informed, are essentially restorations according to contemporary attitudes and tastes.

The recasting of this event in the tradition of terms and meanings is not really a historical project, since the concept of historiography was invented long after Beethoven’s death. It is simply impossible to ascribe a definite meaning to Beethoven’s programme or symphony, nor is it possible to deny the symbolic dimensions of the evening and the work. That is probably why a critic once wrote, “Beethoven’s 9th Symphony is a piece one loves to hate: It’s incomprehensible and irresistible, it’s awesome and naïve.”

Berlin Premiere

Henriette Sontag

It might be worth remembering that Beethoven was adamant that his 9th Symphony should be premiered in Berlin and not in Vienna. His threat to take his symphony to Berlin was real enough as it took a petition signed by many prominent Viennese patrons, friends, financiers and performers for the composer to change his mind.

Why then was Beethoven so unhappy with Vienna? For some years the composer had lamented the changing musical taste of Viennese audiences, who numerously flocked to see the operatic entertainments offered by Rossini and other Italian composers. Beethoven and Rossini probably met once in Vienna in 1822, and supposedly Beethoven counselled his young colleague with the words, “Above all, make a lot of Barbers!”

Ode to Joy

For Beethoven, Rossini was a composer of light comedies, who embraced the “rankest lap of luxury” by pandering to populist demands. Supposedly, Beethoven quipped “Rossini would have been a great composer if his teacher had spanked him enough on the backside.” Whether this meeting and conversation actually took place or not is clearly beside the point, as it quickly became, and still is, part of a much larger narrative.

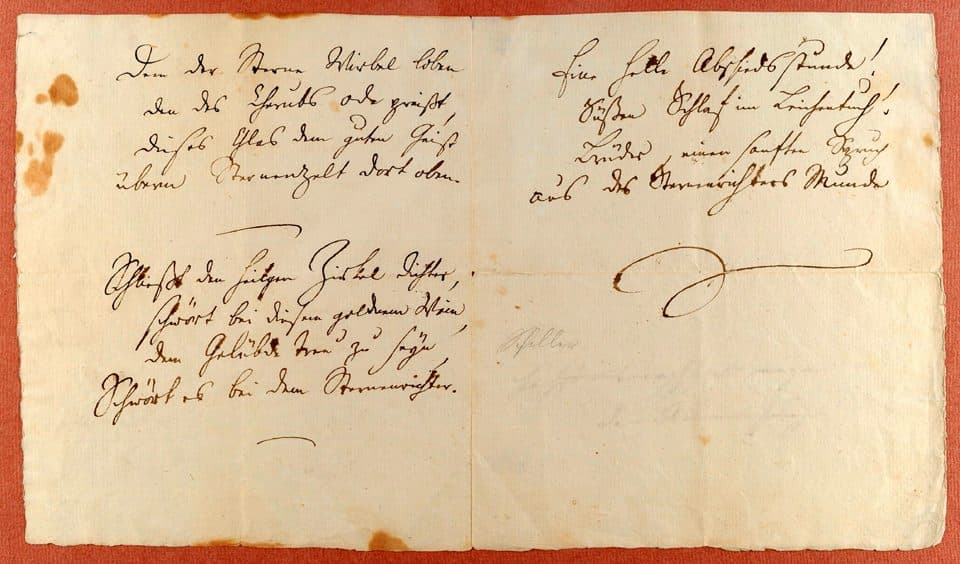

Schiller’s Ode to Joy

By presenting his Ops. 123, 124, and 125 in a single academy, Beethoven was clearly not trying to appeal to popular demands. Rather the opposite, it seems, as a programme of such seriousness, duration and ticket expense, was hardly going to attract the bohemian party crowd. By appealing to the spirit of Romanticism and the shared ideals of humanity as expressed in Schiller’s Ode to Joy, the composer appeared to have made not only a musical point but also issued a decisive cultural statement.

200 years later, the Ode to Joy is the anthem of both the European Union and the Council of Europe. Its described purpose is to “honour shared European values, expressing the ideals of freedom, peace, and unity.” The 2024 re-creation of the 1824 academy still won’t be a crowd magnet, nor will it be an attractive event for most Europeans. However, the statement of intent seems very clear. The utopian ideals expressed in the 9th Symphony, although no longer believable in 2024, still need to provide the fundamental bases of interaction in a world intent on proving the opposite on a daily basis.