by Georg Predota, Interlude

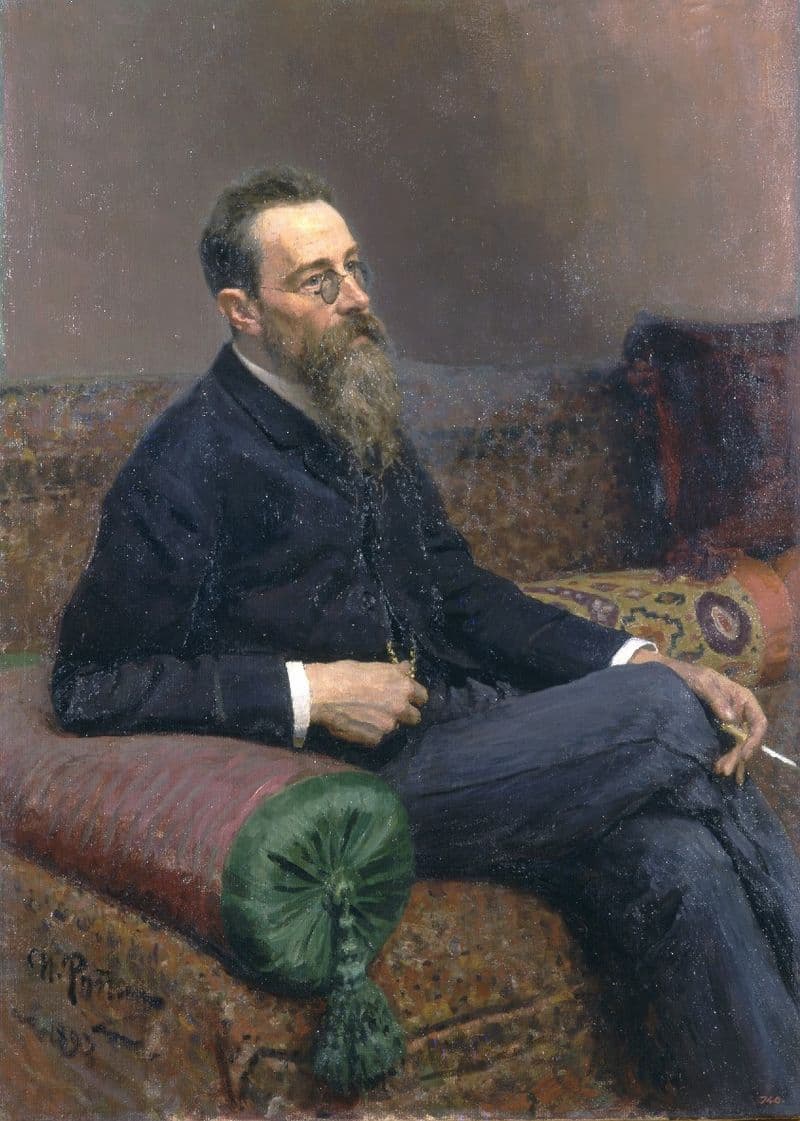

Repin: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Romances gradually evolved from the pastime of the rich and famous into an acknowledged musical genre. As Rimsky-Korsakov wrote in 1897, “I think that in their requests for melodiousness, sing- ability and expansiveness, singers and the public at large are right… short melodies, fragmentation, music departing from harmonies, and demand for dissonances – are things in themselves undesirable… There was a time (I remember it) in the sixties when the majority of Chopin’s melodies were considered weak and cheap music… But nevertheless, pure melody, deriving from Mozart, through Chopin and Glinka is alive up till now, and has to remain alive, for without it the fate of music is decadence.”

On Georgian hills lies night’s darkness;

Aragvi roars before me.

I feel sorrowful and at ease; my sadness is light;

My sadness is full of you,

You, only you…

My gloom is not disturbed or tortured by anything,

And my heart again burns and beats faster because

It cannot renounce love.

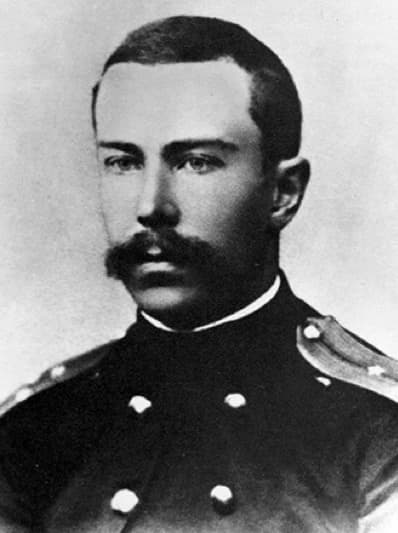

Mily Balakirev

In his autobiography, Rimsky-Korsakov claimed that his first song was a setting of a poem by Heinrich Heine in December 1865. While this particular claim can’t be verified, he did compose 22 Romances during his apprenticeship with Mily Balakirev. Initially, Rimsky-Korsakov was harmonizing the Russian folksongs collected by Balakirev. Rimsky-Korsakov remembers, “Balakirev had at that time a large stock of Oriental melodies and dances. He often played them for others, and me in his own most delightful harmonization and arrangements. My acquaintance with Russian and Oriental songs at the time marked the origin of my love for folk music, to which I devoted myself subsequently.” Rimsky-Korsakov’s encounter with oriental melodies and dances immediately transferred into his romance settings.

Enchanted by the rose, a nightingale

Day and night sings above it;

But the rose listens silently…

In that way a poet with his lyre

Sings for a young maiden;

But the dear maiden knows not

To whom he sings and why

His songs are so full of melancholy.

From the very beginning, Rimsky-Korsakov’s romances have an artistry that is foremost a musical one, as he strove to form a symbiotic relation between the poetic statement and a singable design. Inspired by hearing the soprano Ermolenko-Yuzhina at the house of Mikhail Glinka’s sister, Rimsky-Korsakov issued his Four Romances Op. 2, in 1866.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, 1866

The second song of the set is titled “The Nightingale and the Rose.” Penned by the young Russian poet Aleksei Koltsov in the “Persian style,” the poem is set by Rimsky-Korsakov with a static chordal accompaniment infused with oriental arabesques, with the declamatory vocal line reeling with the agony of the lover’s grief.

Your glance is as radiant as the heavens

With its azure enamel;

Your youthful voice like a kiss

Vibrates and melts away.

Just for the sound of your magical accents,

For your single gaze

I’d gladly give up the hero of the battle –

My Georgian dagger…

The cornerstone of Rimsky-Korsakov’s professional credo was “a scholarly and learned approach to composition technique, diligent attention to all aspects of craft, and the urge to tame musical anarchy and dilettantism.” In his compositional technique, Rimsky-Korsakov was essentially European-trained while at the same time being firmly rooted in the unmistakable Russian music tradition. “He actively pushed the confines in the sphere of harmony, in no small part through the usage of the whole-tone and octatonic scales, which opened up possibilities for a wider harmonic palette and delicious relations between tonalities.”

I bitterly lamented amidst the desert:

“Who from now on will be

As close to my heart as You once were?”

The echo responded: “Alas!”

“How will I live on, sick and morose,

Tormented by ever present sorrow

And many onerous years?”

The echo responded: “Alone!”

“But what should I do? The world is a grave,

Meaningless life is abhorrent to me.

Where is former splendour, pleasure and paradise?”

The echo said: “Dead!”

Apollon Maikov

After having published his Romances Opp. 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8, Rimsky-Korsakov did not return to the genre until the early 1880s. This reawakening coincided with his desire to author a theoretical textbook. As he writes, “When I took over Lyadov’s class in harmony, I grew exceedingly interested in teaching that subject. Tchaikovsky’s system (I followed his textbook in private lessons) did not satisfy me… and I conceived the idea of writing a new textbook on harmony, according to a wholly new system as regards pedagogic methods and sequences of exposition.” For the romance composer, harmony and counterpoint, “providing very many sonorities of great variety and complexity.”

Of what in the quiet night I secretly dream,

Of what in the light of day I think every hour, –

Will remain a mystery to everyone, and even to you, my verse,

You, my flighty friend, my daily consolation,

To you I won’t convey the yearnings of my soul,

Because you might reveal whose voice in the night’s silence,

I hear, whose face appears to me in everything,

Whose eyes shine for me, whose name I

endlessly repeat.

Rimsky-Korsakov once again turned his attention to different matters, and there was an extended interruption in the composition of the romances. In fact, Cesar Cui remarked in 1896, “Rimsky-Korsakov apparently does not have much interest in the genre.” However, during his great Liederjahr of 1897, Rismky-Korsakov composed 47 romances. Yet his approach to vocal style had undergone a noticeable change. The poem for Op. 40, No. 3 “In the Still of Night,” was written by Apollon N. Maykow and carries the subtitle “Elegia.” The music tenderly traces an internal nocturnal dream, with the musical substance entirely derived from the emotional content and diction of the poetry.

Not the wind blowing from on high

Has touched the leaves in the moonlit night –

My soul has been touched by you:

It is aflutter, like the leaves,

It is as sensitive as the lyre’s strings.

The blizzard of life was tearing it apart,

And with the crushing attack,

Whistling and howling, tore the strings,

And covered my soul with icy snow;

But your voice caresses my hearing,

Your touch is as light

As the down flying from the flowers,

Like a breeze of the May night.

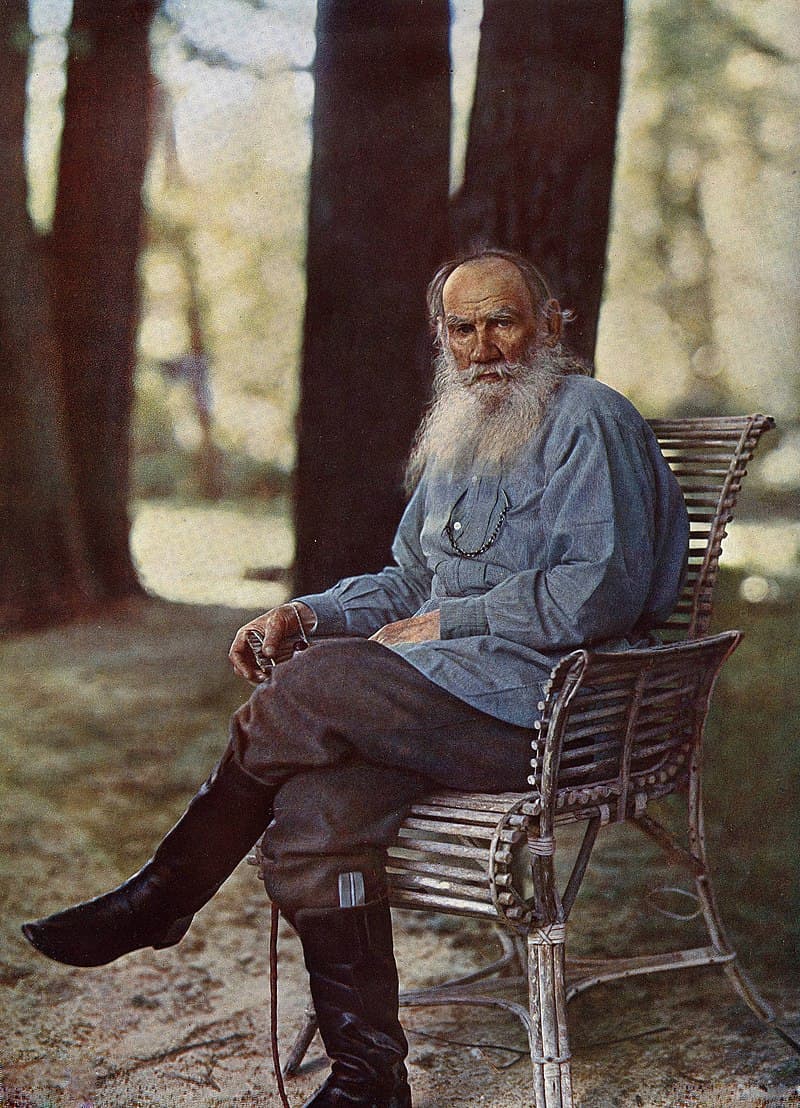

Leo Tolstoy

As Rimsky-Korsakov reports, his method of composition had undergone a significant change. He writes, “I had composed no songs for a long time. Turning to Tolstoy’s poems, I wrote four songs, and the feeling came over me that I was not composing in the same way as I used to. The melody of these songs, following the text, turned out purely vocal with me; that is, it became such at its very birth, with but mere hints of harmony and modulation accompanying in its train. The accompaniment formed and developed after the melody had been composed, whereas formerly, with few exceptions, either the melody was created as if instrumentally, that is, apart from the text, though in harmony with its general purport, or it was stimulated by the harmonic foundation which occasionally preceded the melody.”

I know the reason why by these shores

A mysterious pensive mood seizes the sailors:

A melancholy nymph with flowing tresses,

Half-hidden by rustling reeds,

Sometimes sings a song there

About the silk of her hair,

The azure of her tearful eyes, the pearls of her teeth,

And a heart full of unrequited love.

Passing by in a boat an enchanted sailor

Listening to her song stops rowing;

And, even when she falls silent,

He still imagines for a while the singing above

the waters,

And the nymph in the reeds

With flowing tresses.

Alexander Pushkin

Having found a new method of composition, Rimsky-Korsakov was elated to have discovered, “the true vocal music, and feeling satisfied, too, with my first essays in this direction, I composed song after song to words by Tolstoy, Maykov, Pushkin, and others. In no time at all, I had well-nigh a score of songs already.” Significantly, Rimsky-Korsakov discovered that his new way of composing romances would also lend itself to the writing of operas. As he explains, “I had a feeling that I was entering upon some new period and that I was gaining mastery of the method, which heretofore had been quasi-accidental or exceptional with me.”

Amid a desert, arid and bare,

In soil, flaming with heat,

The Upas tree, like a fearsome guard,

Stands alone in the entire universe.

The nature of the barren steppes

Created it in the day of wrath

And soaked with deadly poison

Its green branches and its roots.

The poison percolates through its bark

Melting from the midday heat,

And congeals by evening

Into a dense translucent resin.

Birds nor beasts roam not near it:

Only a black whirlwind

Occasionally would fly nearby –

And rush away, but already deadly.

And if a wondering cloud would sprinkle

Upon its dense foliage,

From its branches, the toxic rain

Flows down into the sizzling sand.

But a human sent another human

To the Upas tree with a commanding glance;

And he obediently set off on a journey,

Returning by the morning with the poison.

He brought back the deadly resin

And a branch with withered leaves;

The sweat across his pale face

Was flowing in cold streams.

He weakened and laid down

Under a tent upon a trestle-bed,

And the poor slave died

By the feet of an unconquerable sovereign.

Meanwhile the Tsar drenched with that poison

His obedient arrows

And sent around death

To neighbours in foreign lands.

Rimsky-Korsakov later suggested that these romances merely served as preparatory exercises for the operatic compositional spree of his later years. Essentially, he viewed them as studies for finding and perfecting new ideas and methods before implementing them in an operatic context. He also demystified the concept of musical nationalism. “In my opinion,” he writes, “a distinctively Russian music does not exist. Both harmony and melody are pan-European. Russian songs introduce into counterpoint a few new technical devices, but to create a new, unique kind of music, this they cannot do. Russian traits, and national traits in general, are not acquired by writing according to specific rules, but rather by removing from the common language of music those devices which are inappropriate to a Russian style.”

Tormented by spiritual anguish

I dragged myself through a grim desert,

And a six-winged seraphim

Appeared to me at a crossroads;

With his fingers, light as a dream,

He touched my eyes:

They burst open wide, all-seeing,

Like those of a startled eagle.

He touched my ears

And they were filled with clamour and ringing:

I heard the rumbling of the heavens,

The high flight of the angels,

The crawling of the underwater reptilians

And the germinating of the grapevine in the valleys.

He pressed against my lips

And tore out my tongue,

Both exuberant and sly,

And into my frozen lips

The sting of a wise snake

He pushed with his bloody hand.

He cleaved my chest with a sword

And took out my trembling heart,

And thrust into my opened breast

A flaming piece of coal.

I lay in the desert like a corps.

And God’s voice called to me:

“Arise, my prophet, behold and hark,

Submit to my will,

And, traveling across the seas and lands,

Spark people’s hearts with verse.”

Comparable in volume and significance to the romance output of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov’s chamber vocal compositions fully reflect the range of traits and features we find in his larger works. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that he was frequently dubbed the “Singer of the Russian Soul.”