It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, December 26, 2025

Happy New Year 2026 🎉 Best New Year Piano & Orchestra Instrumental Covers

For The Patron: The Jour de Fête Quartet

by Maureen Buja

On Fridays, the publisher Mitrofan Petrovich Belaieff had his musical gatherings, bringing together the cream of the St Petersburg composers. The earlier group, who came together around Mily Balakirev, known as the Mighty Handful, or just The Five (Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov), had done their best to embody Russian national music, but fell apart after the early death of Mussorgsky. The timber merchant Belaieff stepped forward next.

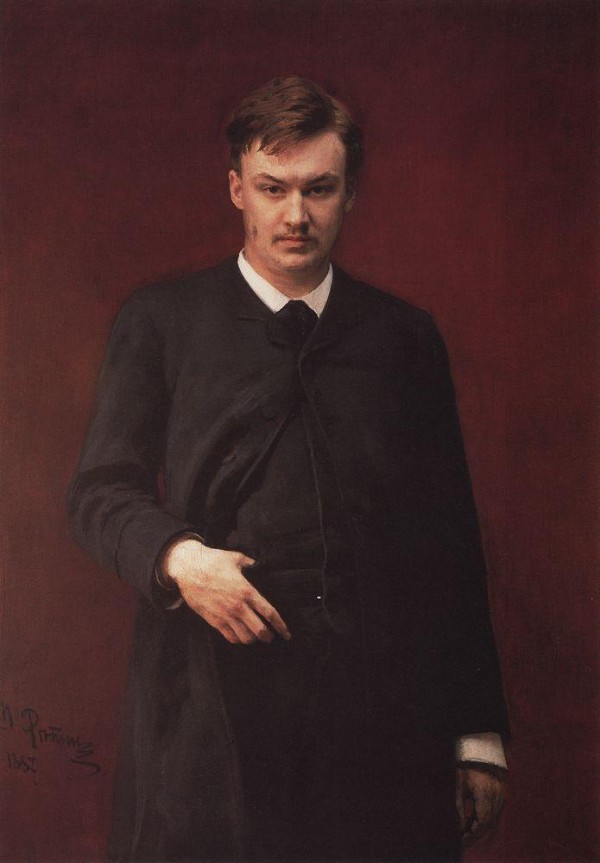

Portrait of Alexander Glazunov

Belaieff, with the family fortune in the timber industry behind him, was also a musician. He played the viola and, through Anatoly Lyadov, was introduced to Alexander Glazunov. In the early 1880s, Belaieff held Friday musical meetings for string quartet concerts at his house. Initially, they were playing through the quartets of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven in chronological order, but soon Russian music was making its appearance.

Portrait of Mitrofan Belaieff by Ilya Repin

Musically, Glazunov was the new driving force behind what became known as the Second Petersburg School. Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov, Glazunov, the critic Vladimir Stassov, and many others flocked to Belaieff’s soirees. Rimsky-Korsakov, Lyadov, and Stassov had been important members or adjuncts to The Five. The Belaieff meetings were never cancelled. Rimsky-Korsakov recalled that if a member of the original quartet fell ill, Belaieff quickly found a stand-in. Belaieff always played the viola in the quartet.

A normal evening would include a concert at around 1 am, after which food and wine flowed. After the meal, Glazunov or someone else might play the piano, either trying out a new composition or reducing a symphonic work to a 4-hand version.

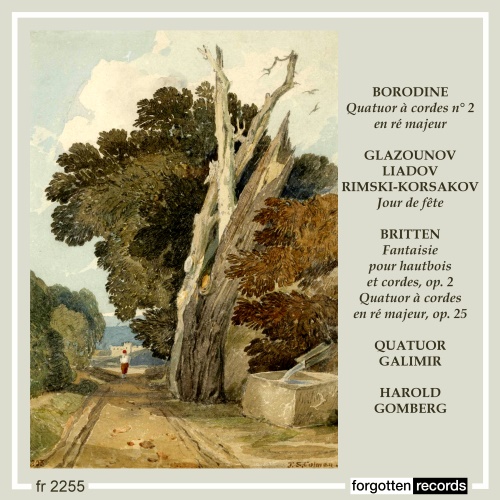

The composers would all contribute to a group project, such as the string quartet for Belaieff’s 50th birthday in 1886, composed by Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Lyadov, and Glazunov. Called the String Quartet on the Theme ‘B-la-F’, using the principal syllables of Belaieff’s last name. A year earlier, Glazunov, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov composed the three-movement ‘Jour de fête’ or ‘Name-Day Quartet’ for their patron.

For the Jour de Fête quartet, Glazunov contributed an opening movement called Les chanteurs de Noël. The Jour de Fête celebrates Christ’s birth, celebrated on January 6-7 on the Orthodox calendar. The Christmas singers bring joy to the festivities.

Felix Galimir at Marlboro

This recording was made in 1950 by the Galimir Quartet. Founded by violinist Felix Galimir (1910–1999) in 1927, the quartet was made up of him and his three sisters (Adrienne on violin, Renée on viola, and Marguerite on cello). They were the right quartet at the right time, recording Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite and the String Quartet of Maurice Ravel under the supervision of the composers, who were present during the rehearsals and recording sessions in 1936. These recordings were awarded two Grand Prix de Disques awards. After fleeing Germany because of his Jewish background, he ended up in Palestine and, together with his sister Renée, was a founding member of what would become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1938, he moved to New York, where he re-founded the Galimir Quartet, this time with members Henry Seigl on violin, Karen Tuttle on viola and Seymour Barab on cello. In New York, he was a member of the NBC Symphony orchestra, concertmaster of the Symphony of the Air, and taught at The Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and Mannes College of Music in New York. In the summers, from 1954 to 1999, he was on the faculty of the Marlboro Music Festival.

Performed by

Galimir Quartet

Recorded in 1950

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for o

Khatia Buniatishvili: Master Pianist or Master of Hype?

By Georg Predota

Khatia Buniatishvili © Gavin Evans

She has been called a “social-media pianist,” accused of cultivating an image at the expense of musical depth. These opposing narratives often clash more loudly than the music itself, revealing as much about our cultural anxieties as about Buniatishvili’s artistry.

Yet somewhere between the extremes lies a far more interesting story. How does a singular performer navigate the fault line between genuine expression and hyper-visibility of the modern classical world?

Self-Made Spotlight

What often gets lost in these polarised assessments is just how shrewd Buniatishvili has been in shaping her career. Long before the magazine covers and viral clips, she had already proven her musical calibre, placing respectably in major piano competitions and earning the approval of figures who cared little for glamour.

Yet she also understood, perhaps earlier than many of her peers, that she wasn’t playing in the same league as Yuja Wang, Daniil Trifonov, or Grigory Sokolov. The era in which runner-up prizes alone could propel a pianist to international prominence was clearly fading.

Rather than waiting for gatekeepers to grant her visibility, Buniatishvili seized the tools of modern media and made herself visible on her own terms, not as a shortcut around musicianship, but as a parallel pathway to an audience that the old model no longer reliably delivered.

Crafting a Persona

Khatia Buniatishvili

Central to this recalibrated path was her self-fashioned image, an image she cultivated with unmistakable intentionality, and something she calls “authentic vulnerability.” Buniatishvili understood that in an age saturated with content, visibility alone was meaningless unless it carried emotional charge.

So she leaned into what audiences already sensed, particularly her intensity at the keyboard, her kinetic presence, the way she seemed to play through emotion rather than merely shaping it. The visual language she adopted, including touches of cinematic glamour, was simply a way of amplifying the magnetism that was already there.

It made her instantly recognisable, fiercely memorable, and yes, sometimes controversial. But it also signalled an artist unafraid to fuse musical vulnerability with a boldly curated aesthetic that challenged long-standing expectations about virtuosity.

Digital Glamour

All of this, however, circles back to an essential point. Buniatishvili can play; everybody can these days. And she often plays with a fluency and fire that justify her broad popularity. Her sound is unmistakable, her instincts bold, and when she connects with a work, the result can be genuinely thrilling.

But the amplification provided by social media does not, in itself, confer artistic genius. Visibility is not vision. Followers are not proof of interpretative depth. The danger lies in confusing the mechanisms that propel a career with the qualities that define a great musician.

Buniatishvili’s online presence may magnify her allure, but it cannot substitute for the hard currency of musical insight. This distinction is increasingly difficult to ascertain, yet vital to maintain in the digital age.

Dual Virtuosity

Khatia Buniatishvili

In the end, Khatia Buniatishvili occupies a curious and unmistakably modern position in the classical music landscape. She is, by any reasonable measure, an able and often compelling pianist. She is certainly capable of moments of real eloquence, technical ease, and emotional charge.

But her true virtuosity may lie not only in her playing but in her ability to navigate and manipulate the currents of contemporary visibility. In a field still negotiating its relationship with image, immediacy, and digital spectacle, she has turned self-promotion into an art form of its own.

Khatia Buniatishvili has shaped her persona just as meticulously as any performance. Whether one admires or resents this dual mastery, Buniatishvili stands as a reminder that in the twenty-first century, artistry and self-fashioning travel side by side. Does hype outstrip substance? Time will tell; the debate continues.