It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, January 6, 2023

Musical Double Takes: Bach, Bentzon, Czerny, Rekhin, Rheinberger, and Madsen

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Johann Sebastian Bach

Score of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier

The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, and the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II are rightfully considered among the most important works in the history of Western music. These works have been highly influential, and various composers have composed complete sets. However, I want to introduce you to composers, who like Bach, did a musical double take and composed multiple sets of preludes and/or fugues in all keys.

Johann Sebastian Bach amazingly wrote two complete sets of preludes and fugues, but the Danish composer and pianist Niels Viggo Bentzon (1919-2000) composed 14 separate sets of 24 preludes and fugues! By any stretch of the imagination, that is an astonishing number of works. They are collectively known as “The Tempered Piano,” and represent 20th-century examples of music written in all 24 major and minor keys.

Niels Viggo Bentzon

Niels Viggo Bentzon

In an interview, the composer referred to his “Tempered Piano as a series of aesthetic paradoxes. By this, I mean an almost complete transcription of the building blocks of classical music. If a Fugue from one of the tempered pianos is crammed with imitation, one can be dead sure that the phenomenon functions differently than in Bach or Handel. In The Tempered Piano, a theme may appear in its entirety at the beginning of the piece, only to change gradually, almost out of recognition, as that particular piece winds to an end.” The composer was once asked about the exact meaning of his compositions, and he responded, “I have to admit with shame that I am virtually seldom inspired. It is just a matter of getting hold of a pencil and firing away.” Bentzon has also composed 24 Symphonies—not ordered according to keys—operas, ballets, concertos, string quartets, and many additional piano works.

Carl Czerny (1791-1857) came from a very musical family. His grandfather was a professional violinist, and his father an oboist, organist, and pianist. Little Carl was a child prodigy, and he started piano lessons with his father at the age of three. By the age of ten, he became a student of Beethoven, and he maintained a relationship with the composer throughout his life. At the core of Carl Czerny’s early piano studies stood Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. We know that he carefully studied this collection during his early lessons with his father. Likewise, the WTC had been fundamental to Beethoven as well.

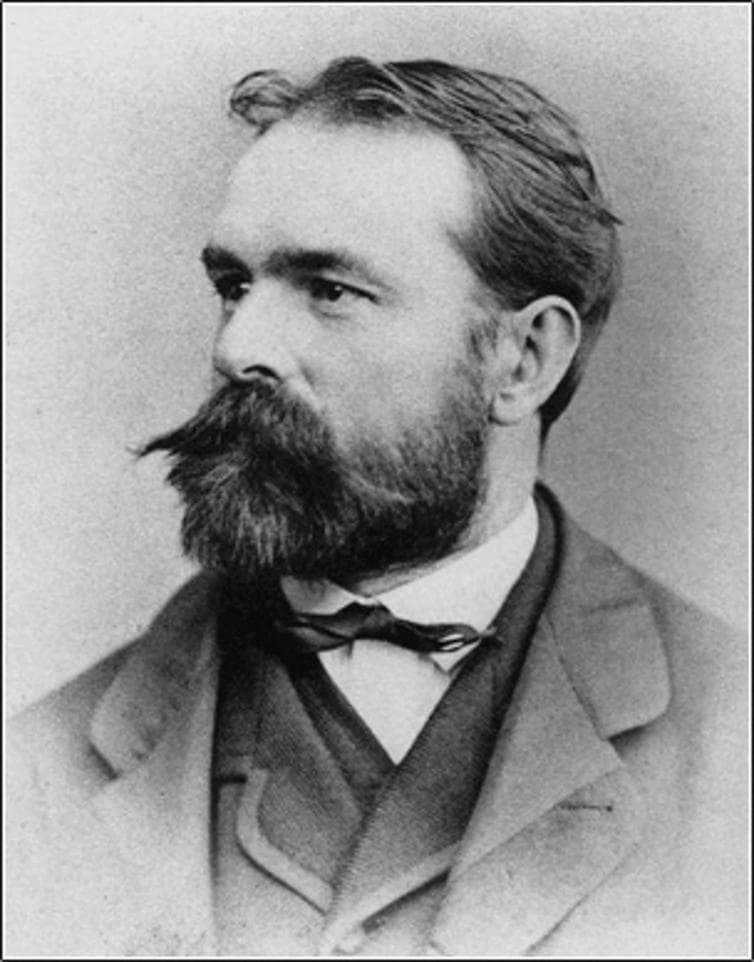

Carl Czerny

Carl Czerny, 1833

Today we know that Czerny produced a collection of exercises and studies that might rightfully be described as “industrial.” He composed a number of fugues early on that became part of his performing repertoire as a concert pianist. Czerny composed at least three complete sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys. The most impressive collection emerges in his Op. 856, in which he tried to update this archaic genre. It has been suggested that Czerny dedicated this set to Liszt, who had been Czerny’s most outstanding student. We don’t know how Liszt reacted to the dedication, but critics were generally dismissive. Robert Schumann “accused Czerny of insisting on an obsolete genre without renewing in any way the classical models established by Bach.” He even found fault with Czerny’s creativity, with the way he avoided the formal procedures that make the fugue interesting: transformations of the subject through augmentation, diminution, inversion, crab canons, and layering two or more themes or using subject and countersubject in the Handel fashion. Although homages to Bach and Handel are frequent, Czerny does attempt to dress his use of strict counterpoint in the characteristics of the emerging gallant style.

Igor Rekhin

Igor Rekhin

Collections of preludes and fugues in all major and minor keys are not exclusively tied to keyboard instruments. Such is the case with Russian composer Igor Rekhin, born in 1941. Rekhin fashioned two complete sets: the 24 Caprices for solo cello, and 24 Preludes and Fugues for guitar. Rekhin composed over 100 works in various genres, but the 24 Preludes and Fugues for solo guitar are unique. The initial idea emerged in 1985, on the 300th anniversary of Bach’s birth. The composer writes, “At the beginning of the work on the prelude and fugue I imagined a musical idea that I subsequently wrote down. I tested that idea on the piano and then elaborated it on the guitar. I quickly found that many ideas that sounded good on the piano were difficult to transplant to the guitar. That path was ineffective, so I changed my approach and just picked up the guitar and began to look for polyphonic solutions.” Critics were enthusiastic, and suggested that the collection “opened the concert repertoire for guitar in a completely new way. Maintaining the tradition of the old polyphonic masters of the lute in a homogeneous connection with the latest styles and trends, including pop to avant-garde, this cycle gives guitarists the opportunity to be placed on par with other traditional concert instruments such as the piano.”

Josef Rheinberger

Joseph Gabriel Rheinberger

Joseph Gabriel Rheinberger (1839-1901) was born in Liechtenstein, and he inherited his musical talents from his mother. He started lessons with the local organist at age five, and two years later he was appointed organist in Vaduz and was writing his first compositions. Against the wishes of his family, Rheinberger went to Munich to continue his studies, and he subsequently held a number of important posts in that city. Among them was the appointment as the instructor in counterpoint at the Royal Academy of Music, and his students included Engelbert Humperdinck, Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, and Wilhelm Furtwangler. Organ music formed the core of Rheinberger’s compositional efforts, and he espoused a conservative musical style influenced by Bach, Mozart, and Haydn. As such, it is hardly surprising to find two sets of compositions in all major and minor keys. His 24 Fughettas Op. 123 are essentially lyric miniatures in a highly contrapuntal style. Rheinberger was also looking to compose 24 organ sonatas in all major and minor keys but sadly died having completed only 20.

Trygve Madsen

Trygve Madsen

The Norwegian composer Trygve Madsen was born in 1940. “I had the good fortune to be born into a family of musicians,” he explains, “my grandfather and his seven sons were all professional musicians. At six I began playing the piano and began composing at about the same age. As my piano playing developed I became increasingly involved in the daily music-making at home, joining in anything from popular songs to sonatas.” Madsen studied with the organist Johannes Almgren, who had been a student of the famous theoretician Hermann Grabner, who in turn had been a student of Max Reger. However, Madsen was not only interested in counterpoint but from an early age, he was also attracted by jazz. He listened to recordings by Erroll Garner, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and Oscar Peterson for hours on end. A clear formative musical influence was provided by Sergei Prokofiev, with Madsen writing ”That was what made me a composer. I realized that this was the way for me; everything came together in Prokofiev’s music. It was like coming home! Prokofiev shaped and molded his musical material in his own way with superb craftsmanship, without violating the rules of music – often infusing it with a liberating sense of humour.” Madsen composed two complete sets of music in all major and minor keys; 24 Preludes, Op. 20 and 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 101. He began work on the full cycle of 24 Preludes and Fugues in 1995, with a clearly laid out play of the order in which the keys would be presented. Bach had ordered his set chromatically, while Shostakovich and Chopin preferred an order according to the cycle of fifths. Madsen, ingeniously, based his collection on the astrological treatise “The Harmony of the Spheres,” by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. Kepler suggested, “the relationship between the planets corresponds to the relationship between musical intervals.” Basing his set on an astrological point of view, Madsen’s system “consists of a row of descending minor thirds interrupted by an ascending tritone. In the next episode of musical double takes, we find music by Charles-Valentin Alkan, Lera Auerbach, Adolf von Henselt, Vsevolod Zaderatsky, Dmitry Shostakovich, Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Louis Vierne, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, and Nikolai Kapustin.

Daniel Barenboim tritt als Generalmusikdirektor der Staatsoper zurück

Nach langer Krankheit dirigiert Daniel Barenboim zwar wieder. Doch seinen Posten als Generalmusikdirektor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden gibt es nun auf. „Leider hat sich mein Gesundheitszustand im letzten Jahr deutlich verschlechtert“, sagt er.

Der seit langem erkrankte Daniel Barenboim tritt als Generalmusikdirektor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden zurück. Das gab der 80-Jährige am Freitag in Berlin bekannt.

„Leider hat sich mein Gesundheitszustand im letzten Jahr deutlich verschlechtert. Ich kann die Leistung nicht mehr erbringen, die zu Recht von einem Generalmusikdirektor verlangt wird“, hieß es in einer Erklärung Barenboims. „Deshalb bitte ich um Verständnis, dass ich zum 31. Januar 2023 diese Tätigkeit aufgebe.“ Er bitte Kultursenator Klaus Lederer um Auflösung des Vertrages zum genannten Zeitpunkt.

Barenboim erklimmt mühsam das Podium

Lederer zeigte sich in einer Mitteilung „überzeugt, dass Daniel Barenboim die richtige Entscheidung getroffen hat“. Die Entscheidung stelle das Wohl der Staatsoper und der Staatskapelle in den Vordergrund. „Dies alles verdient größten Respekt.“

Zum Jahreswechsel zurück ans Dirigentenpult

Barenboim war erst zum Jahreswechsel ans Dirigentenpult zurückgekehrt. Er dirigierte am vergangenen Samstag in Berlin die neunte Sinfonie von Ludwig van Beethoven.

Barenboim hatte Anfang Oktober angekündigt, er müsse sich jetzt so weit wie möglich auf sein körperliches Wohlbefinden konzentrieren. „Mein Gesundheitszustand hat sich in den letzten Monaten verschlechtert und es wurde eine schwere neurologische Erkrankung bei mir diagnostiziert“, schrieb er dazu.

Die Staatsoper musste ein zum Geburtstag geplantes Konzert in der Berliner Philharmonie absagen, bei dem Barenboim Klavier spielen sollte. Zuvor musste Barenboim bereits das Dirigat für die zu seinem Geburtstag realisierte Neuinszenierung von Richard Wagners „Der Ring des Nibelungen“ an der Staatsoper abgeben. Für ihn sprangen Christian Thielemann und Thomas Guggeis am Pult ein. Thielemann vertrat Barenboim auch während der Asientour mit der Staatskapelle.

In jüngster Zeit war Barenboim mehrmals ausgefallen. Im Februar musste er sich einem chirurgischen Eingriff an der Wirbelsäule unterziehen.

dpa/tba

Dancing the Classics: Bach, Schubert, Debussy and Mozart

by Hermione Lai

Some classical music has been specifically written to accompany dance, such as the Baroque dance suite, but I am more interested in dance interpretations of classical music that originally had little or no connection to bodily movement.

The story goes that Johann Sebastian Bach composed his Goldberg Variations for the Russian ambassador to Saxony. Count Kyerslingk suffered from extended bouts of insomnia, and to ease his torment, he instructed his private harpsichordist Johann Gottlieb Goldberg to play for him. Goldberg was a former student of J.S. Bach, and he approached him to compose a piece “which should be of such smooth and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights.” Bach went to work and composed a variations set that has been called “one of the most sophisticated works ever written for the keyboard.”

Tap dancing

The Goldberg Variations have been called “sublime and compassionate, graceful, warm and relentlessly intricate.” There is nothing sleepy whatsoever in the Goldberg Variations when the hands of composer Conrad Tao and the feet of tap dance Caleb Teicher get involved. The supposedly calming music becomes a celebration of being awake. There is nothing but pure happiness in the aria followed by an explosion of rhythmic vitality in the variations. There is no doubt in my mind that this particular version would have greatly cheered up Count Kyerslinn.

Franz Schubert based the concluding song of Winterreise on one of the most powerful poems by Wilhelm Müller. The “Hurdy-Gurdy player” presents a very disturbing picture of the alienation of humanity. As a barefoot man is standing on the ice, even music, “often considered a link with the divine, has become monotonous, automated and indifferent.” A contemporary critic wrote, “Schubert’s music is as naive as the poet’s expressions; the emotions contained in the poems are as deeply reflected in his own feelings, and these are so brought out in sound that no one can sing or hear them without being touched to the heart.”

To me, Schubert’s music presents a melancholic aura that creates a sense of ultimate desolation. This overbearing sense of anguish and despair becomes visible in the movements created by the featured Saarländisches Staatstheater Ballet production. There is a lot of focus on bare feet, and what a powerful and highly emotional way of expressing that the plate of the hurdy-gurdy player will remain empty forever.

The French poet Paul Verlaine wrote his poem “Clair de lune” (Moonlight) in 1869. It is an ambiguous description of a moonlit masquerade ball, alternating moments of joy and sadness. The poet takes us on a journey of self-discovery as he gets in touch with his soul in hopes of finding himself. He is looking for all kinds of distractions to feed to his soul in the form of masks, singing, and dancing. The second stanza is devoted to ease his soul with the sound of melody, and in the concluding stanza the poet acknowledges the picturesque beauty of the moonlight. Claude Debussy composed two settings of “Clair de lune,” plus an instrumental version for his Suite bergamasque. Without doubt, it is the composer’s most famous piece for piano, and it further inspired the French dancer, choreographer, and artist Yoann Bourgeois. He has been called a “dramatist of physics,” and his gravity-defying performance transports us to a place and time “where time has no meaning.” Will he find what he is looking for?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed his cantata Davide penitente on commission from the benevolent society for musicians. The text expresses repentance during Lenten season, and it supposedly helps to recognize our sinfulness, express our sorrow and ask for God’s forgiveness. In the mind of the French horse trainer and film producer Bartabas, born Clément Marty, Mozart’s cantata was the perfect match for an equine ballet; that’s right, a ballet performed by the horses and riders of the National Equestrian Academy of Versailles.

Equestrian Ballet © Bruce Adams

He placed the performance into the “Felsenreitschule,” a 300- year old Salzburg venue that was originally built for equestrian performances. Once you place a period instrument ensemble and vocalists in the former audience arcade, you experience a “performance submerged in an atmospheric darkness, lending it something of the sacred.” It certainly is a fascinating interplay between horse and human, music and movement, and light and costumes. Personally, I love it!