It’s all about medieval warfare, and unable to flee the Tudor cavalry, he would be captured or killed very soon. No wonder he was desperate enough to hypothetically trade his crown and kingdom for a horse.

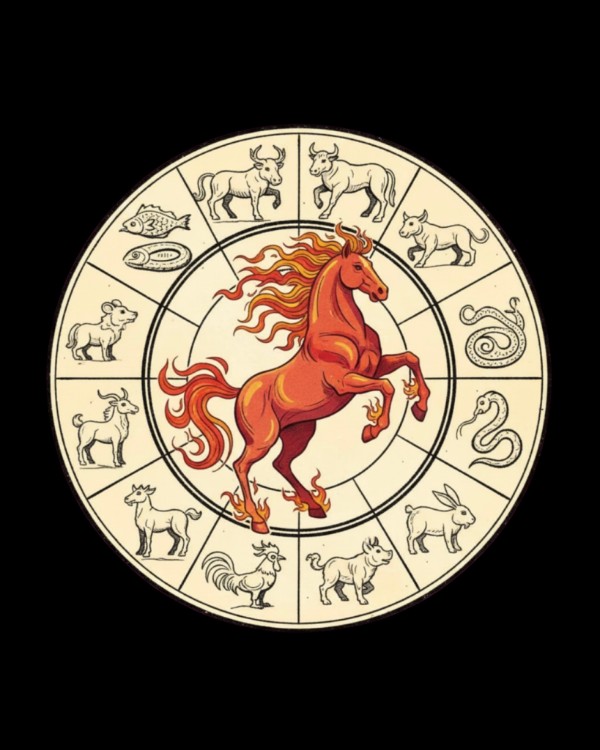

There is no such desperation in 2026, when the Horse becomes the zodiac for the Chinese New Year, running from 17 February 2026 to 5 February 2027.

Recent years of the Horse have included 2014, 2002, 1990, 1978, 1966, and 1954. And the next Horse year will be celebrated in 2038. So, let’s have a look at the 7th animal in the cycle of the Chinese zodiac signs.

Galloping into Greatness

According to Chinese astrology, Horses are confident, agreeable, and responsible, although they also tend to dislike being reined in by others. They are fit and intelligent, adore physical and mental exertion, yet they are also easily swayed and impatient.

Even more significantly, this will be the year of the Fire Horse. This promises a year of positivity because movement is always considered good. This year is for progress, a new start, bold decisions and dramatic shifts.

It’s certainly best to ignore the curse of the Fire Horse, a superstition that holds that women born in that specific year are ill-tempered, headstrong, and fated to bring ruin to their families or cause their husbands’ deaths.

Finance and Opportunities

In terms of career and finance, there are new opportunities waiting. That may include career shifts; however, be careful with impulsiveness or emotions taking centre stage. This is particularly true around mid-year, as mental and emotional breakdowns may present challenges.

Keep up the constant networking, acquire new skills, and effective time management is a powerful catalyst for overall success. You must be mindful of impulsive financial decisions, however. Avoid overspending on vacations, gifts for yourself and others.

Don’t borrow or lend out large sums of money, otherwise your long-term economic success will be in jeopardy. For 2026, consistent savings and long-term risk-averse investments are your ticket to wealth.

Love and Lovers

The Year of the Fire Horse may hold surprises and excitement in the romance department. Since Horses are energetic, lively, and generous, they are certainly popular in the romance department. When it comes to love compatibility, their hot temper and stubborn nature means that they tend to gravitate towards romantic partners who are more easy-going and gentle.

Tigers and Horses are temperamental, hot-headed, and often cocky, but in the love department, they bring out the best in each other and allow the other to grow. It’s as if both the Tiger and the Horse finally have someone who can keep up with their own breakneck speed.

Dogs and Goats are also beautiful matches for the passionate Horse. However, you must stay away from the Rat and the Ox. Such relationships result in frequent conflicts that neither will bother to resolve. Horse loves freedom, which makes Ox feel insecure. What started quickly as a passionate love affair is more likely to result in a bitter breakup rather than a happy marriage.

Wellbeing and Luck

When it comes to health, Horses are very healthy, most likely because they hold a positive attitude towards life. However, heavy responsibility or pressure from their jobs may make them weak. As such, Horses shouldn’t do overtime very often or go home late. They should also refuse some invitations to parties at night.

Lucky numbers in the Year of the Horse are 2, 3, and 7, and numbers that contain them. For your lucky colours, look towards green and yellow, and your lucky flowers are calla lily and jasmine. As for lucky directions, always head east, west, and south.

You should definitely avoid the unlucky colours of blue and white, and your unlucky numbers are 1, 5, and 6. And if you’re on the go, avoid moving north and northwest. And finally, know that you are in good company as famous people born in the Year of the Horse include Isaac Newton, Neil Armstrong, James Cameron, and Max Planck.

To all Interlude readers, we wish you a wonderful Year of the Fire Horse, Gong Hei Fat Choy!