It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Tuesday, September 9, 2025

Haydn: Symphony No. 94 in G major “Surprise”

Friday, July 18, 2025

Joseph Haydn: 10 Most Ingenious String Quartets

by Hermione Lai

Joseph Haydn

Written primarily between the 1750s and 1790s, these works showcase his ingenuity, featuring sparkling melodies, intricate counterpoint and really clever structural surprises.

Drawing from Haydn’s extensive catalogue is no easy task, but we’ve selected 10 of Haydn’s most ingenious string quartets. That selection is based on their musical inventiveness, historical significance, and influence on subsequent generations of composers.

So let’s get started with his Op. 20 set of string quartets, representing Haydn’s early experiments that defined the conversational nature of the genre.

String Quartet in D Major, Op. 20, No. 4, Hob. III:34 (1772)

The six “Sun” quartets of 1772 shook up the classical music world in 1772. Haydn was in his late 30s and working for the Esterházy family. The Op. 20 quartets came at a time when Haydn was pushing boundaries, blending the elegance of the gallant style with the emotional depth of the “Sturm und Drang” literary movement.

Op. 20 No. 4 was written for four skilled players, so Haydn could be adventurous. He treated all four instruments, two violins, viola, and cello, like equal partners. This was pretty radical as the first violin would normally hog the spotlight.

This quartet is not a solo act, but a conversation. It’s funny, tender, and clever all at once. It’s like friends jamming together, trading ideas and laughs. This quartet is the perfect entry point in the wonderful and human world of Joseph Haydn.

String Quartet in F Minor, Op. 20, No. 5, Hob. III:35 (1772)

Compared to the sunny D-Major quartet, the Op. 20 No. 5 in F minor has a darker and more introspective character. It reflects the “storm and stress” trend at the time, putting a premium on dramatic and emotional intensity.

The opening movement is especially intense, unfolding from a brooding theme through a number of intricate motivic developments. There is plenty of lyrical melancholy in the slow movement, and just listen to the double fugue in the finale. After all, Haydn was a master of counterpoint.

This timeless gem is so emotionally rich. It is a musical journey through tension, calm, and eventual revolution. And you certainly need expert musicians to bring out the raw energy and nuance, mixing depth and accessibility.

String Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 33, No. 2, Hob. III:38, “Joke” (1781)

The Opus 20 quartets turned Haydn into a superstar in the musical world. One decade later, he further refined the genre with more polish and playfulness in his Op. 33 set. As Haydn himself said, these works were written in “a new and special way.”

The Op. 33 are often called the “Russian” quartets, because they are dedicated to the Grand Duke Paul of Russia. Some scholars theorise that these quartets might have been the inspiration for the six Mozart string quartets dedicated to Haydn.

The most famous of the set earned the nickname “Joke” because of the mischievous ending of the Finale. However, the entire quartet is packed with Haydn’s trademark humour and surprises. It is light-hearted yet sophisticated, showcasing the composer’s ability to make complex music feel effortless. Just goes to show that classical music does not have to be deadly serious.

String Quartet in G Major, Op. 33, No. 5, Hob. III:41 (1781)

Another gem from the Op. 33 set is the quartet No. 5 in G Major. It sometimes carries the nickname “How Do You Do?” for its quirky and conversational opening. This quartet presents a perfect blend of elegance, wit, and warmth.

Haydn called the Op. 33 “new and special,” likely because of their polished structure, lyrical themes, and the equal roles for all four instruments. Each movement has its own character, from the musical handshake of the opening to the warm and lyrical slow movement. The Scherzo is a lively dance with a rustic edge, and the Finale is a set of variations on a simple and catchy tune with folk-song character.

Op. 33 No. 5 is a crowd pleaser because of its sunny glow, catchy themes, and some subtle humour. It’s a perfect blend of sophistication and fun, full of infectious energy and momentum.

String Quartet in D Major, Op. 64, No. 5, Hob. III:63, “The Lark” (1790)

Nicknamed “The Lark” for its soaring and birdlike melody in the opening movement, the string quartet Op. 64, No. 5 represents a polished example of Haydn’s ability to blend the emotional depth of his earlier works with a polished and accessible style that greatly appealed to audiences.

This quartet is less experimental than his Op. 20 but more refined than Op. 33, showcasing Haydn’s mastery of balance. We find catchy tunes, a tight structure, and it’s a performer’s delight and a listener’s joy.

Each movement has its own personality, from the chatting bird in the opening to a slow movement of pure warmth. The minuet has a playful spin, and the high-energy Finale is like a musical game of hot potato. It certainly sparkles with clarity and charm.

String Quartet in D Minor, Op. 76, No. 2, Hob. III:76, “Fifths” (1797)

The six quartets of Op. 76 are ambitious late works with advanced forms and thematic unity. Composed in 1797, they are among Haydn’s final and most celebrated contributions to the genre.

At the age of 65, Haydn was a global superstar, having returned from his triumphant tours to London. This trip had given him new ideas, and he now blended technical brilliance, emotional depth, and a highly polished style that appealed to both players and audiences. And the Op. 76 No. 2 is a masterpiece, bold, emotional, and packed with Haydn’s wit and wisdom.

Nicknamed “Fifths” for the stark and descending fifth motif in the opening movement, the work opens with a tense and conversational energy. The warm D Major in the slow movement provides a lyrical and playful breather, but the Menuetto is back in the minor key. Sometimes it is nicknamed the “Witches Minuet.” The Finale is a whirlwind based on a fiery, folk-inspired theme.

String Quartet in C Major, Op. 76, No. 3, Hob. III:77, “Emperor” (1797)

Nicknamed “Emperor” for its majestic second movement, Op. 76 No. 3 is one of Haydn’s finest works in the genre. It is a masterpiece of balance, juggling grand, lyrical and humorous elements in a clear and approachable style.

The “Emperor” nickname comes from the second movement, a set of variations on Haydn’s anthem “God Save Emperor Francis,” composed in 1797 as a patriotic response to Napoleon’s rise. The simple and noble melody undergoes four variations that transform the theme while keeping its dignity completely intact.

The opening movement is a burst of energy, sounding a bold and fanfare-like theme in the first violin. And just listen to the sudden pauses, harmonic twists, and playful interplay between all four instruments. The minuet has a rustic edge while the Finale is once more a high-octane affair.

String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 76, No. 4, Hob. III:78, “Sunrise” (1797)

Another gem in the Op. 76 set is the string quartet in B-flat Major, No. 4. It earned the nickname “Sunrise” from the opening of the first movement. A soaring violin melody rises over a gentle accompaniment, resembling the sun peeking over the horizon.

It is a magical moment that sets a joyful tone. The mood quickly turns playful with a bouncy second theme and lively interplay between the four instruments. The slow movement, in turn, is a soulful gem, with a tender and hymn-like melody that is almost orchestral in texture. Intimate and heartfelt, it provides a moment of quiet reflection.

The minuet is again a rustic dance with Haydn adding quirky offbeat accents and dynamic shifts to keep it cheeky. What a charming mix of elegance and earthiness. And then there is the infectious rhythm of the rollicking Finale. Op. 76 No. 4 is a work of sheer beauty and charm, blending accessibility with sophistication.

String Quartet in D Major, Op. 76, No. 5, Hob. III:79 (1797)

Op. 76, No. 5 in D Major is a radiant and lyrical work that is often considered among Haydn’s finest string quartets. Known for its serene and songlike qualities, this quartet does not have a catchy nickname, but its warmth and elegance make it a standout.

It is a gem for its lyrical and balanced structure, and certainly more introspective and serene. The sunny D Major feels like a warm embrace, and Haydn once again blends sophistication with charm and vibrant energy.

The heart of this quartet is the deeply expressive slow movement scored in the unusual key of F-sharp Major. Sounding a unique and glowing warmth, the melody is soulful and expansive, with a touch of melancholy. It’s like a private confession, both tender and profound. On account of this movement, some commentators have called it the “Graveyard Quartet.”

String Quartet in G Major, Op. 77, No. 1, Hob. III:81 (1799)

Haydn playing a string quartet

Let us conclude this blog on the 10 most ingenious string quartets by Joseph Haydn by featuring his Op. 77, No. 1. It represents a vibrant and polished work that sounds the culmination of Haydn’s quartet writing.

This work was among his final contributions to the genre he helped to perfect. This quartet is the culmination of his craft, blending the emotional depth of his late style, the polish of his London visits, and his lifelong love of surprise and interplay.

The opening movement presents a flowing theme in the first violin contrasted by a dance-like second theme. The slow movement is a lyrical gem, and the minuet is full of musical mischief. The folk-inspired theme of the Finale is passed among the quartet like a musical relay, and the high-spirited finish simply makes us smile.

Joseph Haydn mastered the string quartet genre by transforming it into a dynamic and conversational form where all four instruments share equal roles. From the Op. 20 to the Op. 77, he blends structural brilliance with emotional depth and incredible humour. Haydn set the standard for the quartets of Mozart, Beethoven, and beyond.

Wednesday, June 4, 2025

Saturday, January 18, 2025

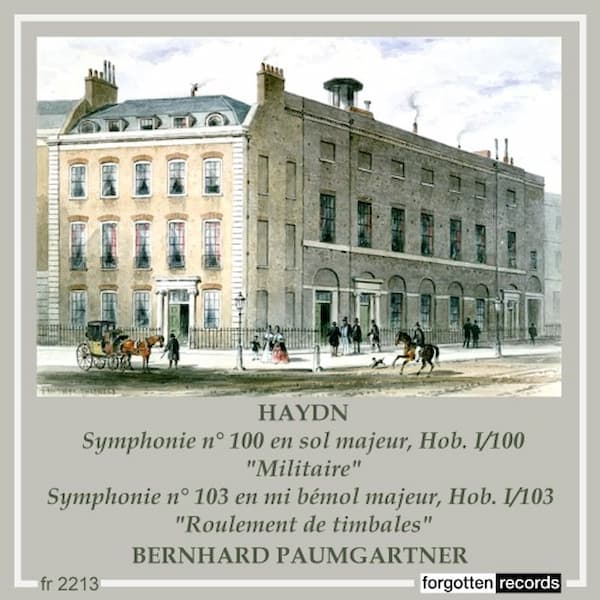

Impressing London: Haydn’s Symphony No. 100

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

Thomas Hardy: Haydn, 1791 (London: Royal College of Music)

He had been commissioned by Johann Peter Salomon to write 6 new symphonies for the start of Salomon’s new subscription season. Haydn had met Salomon when the impresario met him in Vienna and succeeded in getting him to travel to England, first in 1791—1792 and then in 1794–1795. The acquaintance suited both – Haydn needed the exposure, and Salomon needed material for his concerts. For Salomon and London, Haydn wrote 12 symphonies (Nos. 93 to 104), first known as the Salomon Symphonies and now as the London Symphonies.

Thomas Hardy: Johann Peter Salomon, ca 792 (London: Royal College of Music)

Symphony No. 100 in G major was played on 31 March 1794 in the Hanover Square Rooms, i.e., in the heart of fashionable London. The original title for the work was the Grand Military Overture, due to the use of kettledrums and other percussion in the second movement. The end of the last movement sees the reappearance of the kettledrums and military percussion, tying the work together.

The final movement is a rondo, and the recurring main theme became widely popular in England, where it would appear as a dance theme in ballrooms around the country, anxious to reflect what was happening in London.

This recording was made in 1960, with Bernhard Paumgartner leading the Camerata Academica of the Salzburg Mozarteum.

Bernhard Paumgartner

Bernhard Paumgartner (1887–1971) was a leading Austrian composer, conductor, and musicologist. He taught at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, where he was Herbert von Karajan’s composition teacher and brought out his conducting skills. He was an important musical focus for the city, being one of the founders of the Salzburg Festival.

The Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg has a very direct connection with the Mozart family – it was founded in 1841 with the help of Wolfgang’s widow Constanze and his sons, Franz Xaver and Karl Thomas, as part of the Cathedral Music Association and Mozarteum that Constanze was promoting. The orchestra was named the Mozarteum Orchestra in 1908.

Performed by

Bernhard Paumgartner

Camerata Academica du Mozarteum de Salzbourg

Recorded in 1960

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Sunday, January 5, 2025

F.J. Haydn: Symphony nº 101, "The Clock" - Egarr - Sinfónica de Galicia

Wednesday, August 21, 2024

Haydn Symphony No. 101 'The Clock' by Adam Fischer & Danish Chamber Orchestra

Sunday, May 5, 2024

Haydn: Piano Concerto in D No. 11 | Adam Balogh

Sunday, September 24, 2023

Haydn - Symphony No. 104 - London (Proms 2012)

Sunday, May 28, 2023

Why Listen to Haydn? His Life and Music

Sunday, February 26, 2023

Haydn Symphony No. 49 in F minor ' La Passione '

Monday, November 21, 2022

Joseph Haydn / Symphony No. 45 in F-sharp minor "Farewell" (Mackerras)

Friday, October 28, 2022

Who Got It Right and Who Got It Wrong? Critics and Composers

by Maureen Buja

Here, John Gregory, writing in 1766 in his A Comparative View of the State and Faculties of Man with Those of the Animal World, had this to say about what composer?

‘[The style of COMPOSER] sometimes pleases by its spirit and a wild luxuriancy … but possesses too little of the elegance and pathetic expression of music to remain long in the public taste.’

Hmmm. So we want a mid-18th century composer who had spirit and a sense of luxury but lacked elegance…. Mozart? Hummel? No, they’re too late. Gregory was referring to the style of the music of Haydn, who, of all composers of his era, has remained in the public taste where so many of his contemporaries have vanished.

Hardy: Joseph Haydn, 1791

We have two composers with two very different views of conductors. The first, a composer, suffered poor performances in the hands of bad conductors:

‘Conducting is a black art.’

The other, a conductor himself, downplayed the difficulties in a letter to his 10-year-old sister:

‘It’s easy. All you have to do is wiggle a stick.’

It was Tchaikovsky who held the first opinion, given in 1909, and Sir Thomas Beecham in the second quote.

Reutlinger: P.I. Tchaikovsky, c. 1888

Sir Thomas Beecham, 1948

Richard Strauss, on the other hand, felt that certain sections of the orchestra needed to be quelled at all times:

‘Never let the horns and woodwinds out of your sight. If you can hear them at all, they are too loud.’

Igor Stravinsky , himself a composer and a conductor, saw danger in the field of conducting:

‘”Great” conductors, like “great” actors, soon become unable to play anything but themselves.’

and

‘Conducting is semaphoring, after all.’

Richard Strauss conducting

Stravinsky conducting

He also viewed conductors as the ‘lapdogs’ of musical life…which poses an interesting question of which side of Stravinsky was making that statement!

Very few composers or performers had anything good to say about critics.

Richard Wagner thought that ‘the immoral profession of musical criticism must be abolished,’ whereas Beecham saw the problem as one of lack of musical feeling, saying ‘…so often they have the score in their hands and not in their heads.’

Aaron Copland thought that ‘if a literary many puts together two words about music, one of them will be wrong’.

And the critics strike back:

George Bernard Shaw, when accused of being too critical: ‘No doubt I was unjust; who am I that I should be just?’

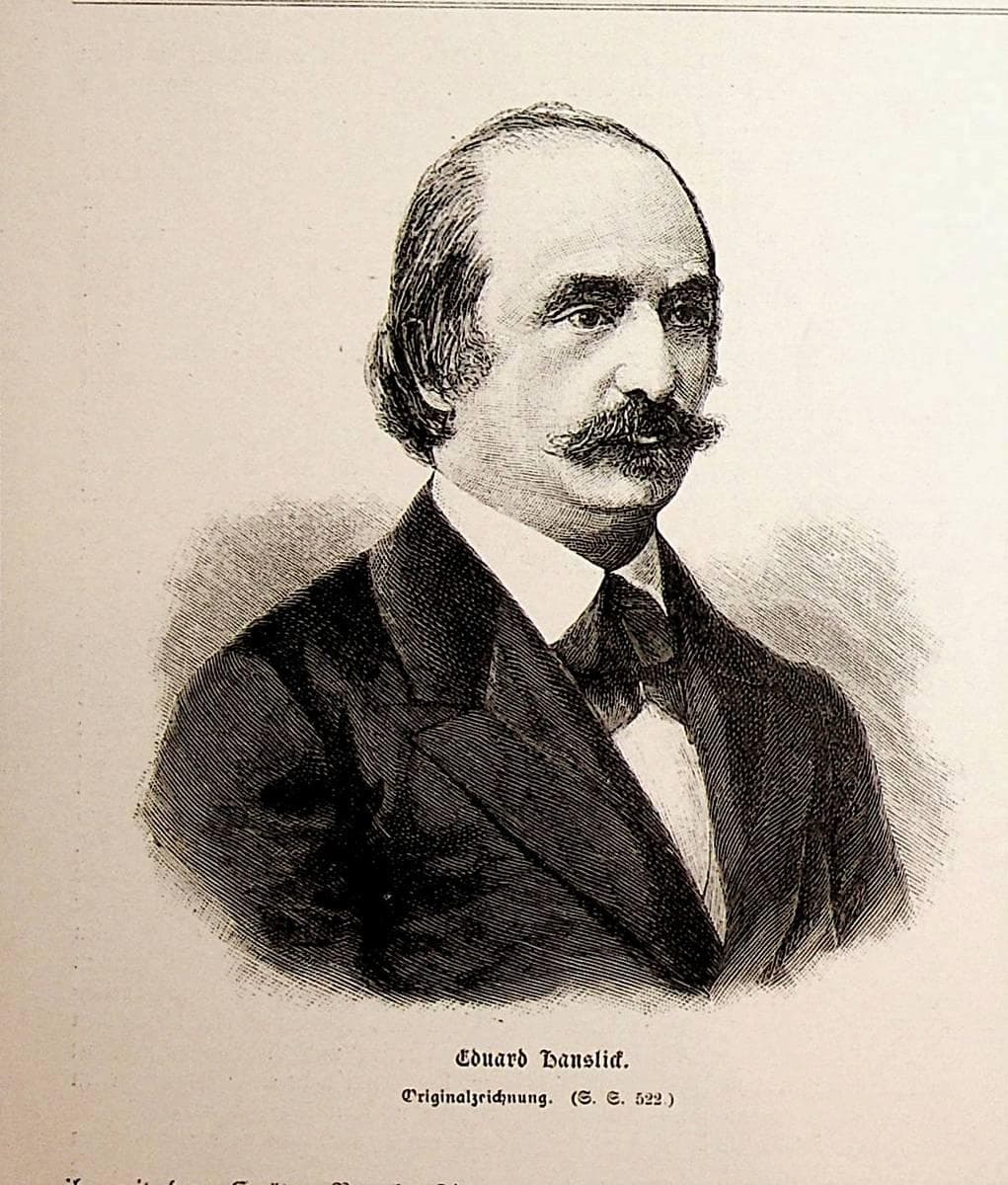

Eduard Hanslick, who wielded great power as critic, took an uncritical view of himself: ‘When I wish to annihilate, then I do annihilate.’

Eduard Hanslick

Oscar Wilde found Chopin to be too emotional: ‘After playing Chopin, I feel as if I had been weeping over sins that I had never committed, and mourning over tragedies that were not my own.’

Sometimes composers are most caustic about their contemporaries. Wagner wondered this about the legacy of Rossini: ‘After Rossini dies, who will there be to promote his music?’

Stravinsky pondered about South American music: ‘Why is it that whenever I hear a piece of music I don’t like, it’s always by Villa-Lobos?’

Some composers write about what they are proudest of. Modest Mussorgsky, known for his songs as much as his symphonic music and opera, said in a letter in 1868 ‘my music must be an artistic reproduction of human speech in all its finest shades’.

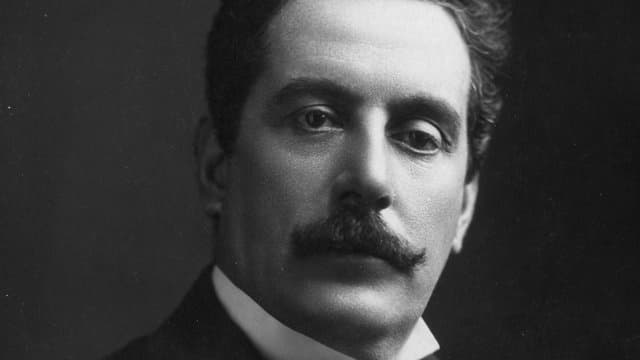

Puccini, understating his talents simply said ‘God touched me with His little finger and said “Write for the theatre, only for the theatre.”’

Giacomo Puccini

Rossini, never one to understate his skill, remarked ‘Give me a laundry-list and I’ll set it to music.’

Stravinsky, who was often so far ahead of his contemporaries musically as to be in another world, said ‘Silence will save me from being wrong (and foolish), but it will also deprive me of the possibility of being right.’

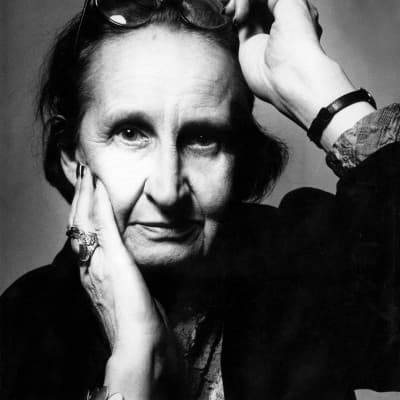

Elisabeth Luytens, who parlayed her contemporary sound into really effective music for British horror films, called her own style ‘eerie weirdness’.

Elizabeth Lutyens

Opinions, opinions … everyone has opinions. Some of them can make us ponder (‘Wagner has lovely moments but awful quarters of an hour’ – Rossini), others make us laugh (‘Hell is full of musical amateurs’ – George Bernard Shaw), and others make us angry (‘There are two kinds of music: German music and bad music.’ – H.L. Mencken) – what’s your opinion?

Wednesday, June 1, 2022

Best Songs in D Minor

by Hermione Lai , Interlude

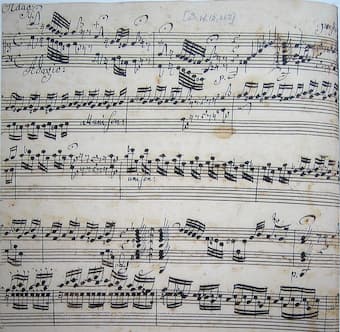

Bach’s Toccata in D minor 18th century copy by Johannes Ringk

Sometimes, I really don’t understand the descriptions assigned to particular keys. When it comes to D minor, we can read that it represents “dejected womanhood which broods on notions and illusions.” I guess it’s a pretty fancy and period description of a scorned woman in love? Others have said that D minor “expresses a subdued feeling of melancholy, grief, anxiety, and solemnity.” Whatever the case may be, some of the most famous and popular classical pieces ever are written in D minor. And here is my list of personal bests.

Bach: Toccata and Fugue in D minor

I can tell you that it was not a very easy choice because of all the gorgeous compositions in D minor that I have to leave out. However, for me it’s all starting with the Toccata and Fugue in D minor by Johann Sebastian Bach. Today that song is used in a variety of popular media, ranging from film, video games and ringtones. But the association today is not melancholy or a scorned woman in love, but sheer terror. This association with horror and Halloween first appeared in a 1962 film adaptation of “The Phantom of the Opera.” It just goes to show that specific associations are easily formed in connection with visual media, but the D minor Toccata and Fugue is still a most powerful composition, and certainly one of the best songs in D minor.

Mendelssohn: Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor

Portrait of Felix Mendelssohn by Wilhelm Hensel, 1847

Felix Mendelssohn learned a lot from the music of Bach. In fact, he was responsible that the music of Bach found its rightful place on the world’s concert stages. Mendelssohn looked at the styles and compositional techniques of the past and developed a highly personalized music style. Not everybody was enthusiastic for Mendelssohn to go back in time, and Berlioz once said, “Mendelssohn paid too much attention to the music of the dead.” And the always-punchy critic and playwright George Bernard Shaw compared Mendelssohn to a senile academy professor whose exercises in a dead musical language “are as trivial as they are tedious.” Then as now, it’s difficult to please the critics. Mendelssohn complete his piano trio in D minor in 1839, and Robert Schumann wrote in his review that “Mendelssohn is the Mozart of the 19th century, the most illuminating of musicians.” There is a good bit of melancholy yearning in the opening movement, and the slow “Andante” is actually a song without words that turns to passion. The scherzo is light and airy, and it all ends with a passionate rondo. For me personally, this is one of the most powerful and best songs in D minor ever.

Mozart: Requiem

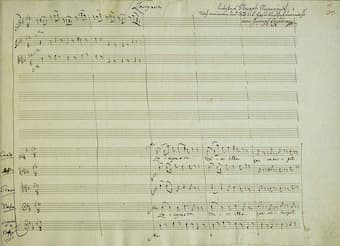

Mozart’s Requiem

Since the key of D minor is supposed to express grief and solemnity, it’s not surprising to find a good number of Requiems in that category. Composers who have written Requiems include Bruckner, Reger, Fauré, and probably most famously, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The passionate lover of music, Count Franz von Walsegg commissioned the work for his twenty-year old wife Anna, who had sadly passed away.

The Count was a fellow Freemason, but as we all know, Mozart himself died before he could complete the composition. Sorry to disappoint all fans of the movie Amadeus, but Salieri had nothing to do with the Requiem or with Mozart’s death. Mozart’s wife Constanze hired several composers to finish the piece and deliver it to the Count. Constanze did suggest that her husband actually believed that he was writing the requiem for his own funeral. Whatever the case may be, it is one of the most powerful classical compositions I know, and it certainly is one of the best songs in D minor.

Haydn: Symphony No. 80 in D minor

Portrait of Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791

D minor seemed to have been a highly popular key for composing large-scale symphonies. We have symphonies No. 1 by Dohnányi, Ives, Rachmaninoff and Richard Strauss. Prokofiev and Balakirev wrote their 2nd symphonies in D minor, the same key used by Bruckner in his symphonies No. 3 and No. 9. Dvořák composed his symphonies No. 4 and No. 7 in D minor, and there are also symphonies by Schumann, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams, Glazunov, and of course the monumental symphony No. 9 by Beethoven. Which one is actually my favorite? To tell the truth, I really can’t decide. So I went back to the father of the symphony, Joseph Haydn, and I found a delightful storm and stress symphony in D minor. His 80th symphony probably dates from 1784, and for some reason it does not have a nickname. However, it is a symphonic gem and Haydn showed everybody coming after him what was actually possible in a symphony. And it is for that particular reason that Haydn’s 80th is my representative for symphonies in D minor.

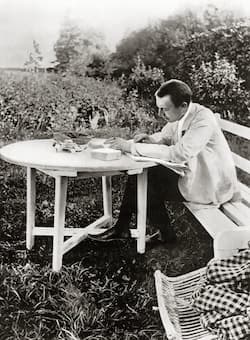

Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30

Rachmaninoff proofing a manuscript

Some composers are actually rather difficult to read. Sergei Rachmaninoff was clearly one of the last great pianist-composers in a long tradition stretching back to Mozart, Beethoven, Liszt and Brahms. He proudly suggested that “a composer’s music should express the country of his birth, his love affairs, his religion, the books which have influenced him, and the pictures he loves… My music is the product of my temperament…” Rachmaninoff was fiercely egotistic in artistic matters, but also frequently depressed without any specific cause. Very few people ever heard him laugh, and only occasionally did he crack a rare smile. He was often grave in expression and mannerism, and seemed to have been stuck in prolonged periods of philosophical longing and melancholy. Almost sounds like Rachmaninoff could be considered the poster child for D minor. And wouldn’t you know it, he did write a great number of works in that particular key, including the fabulous 3rd piano concerto. It is without doubt one of the all-time best songs in D minor. As you can tell, the key of D minor was really popular with composers, and I have tried to find my favorite songs; what is yours? Next time, I will take a look at the best songs in the cheerful key of B-flat major.