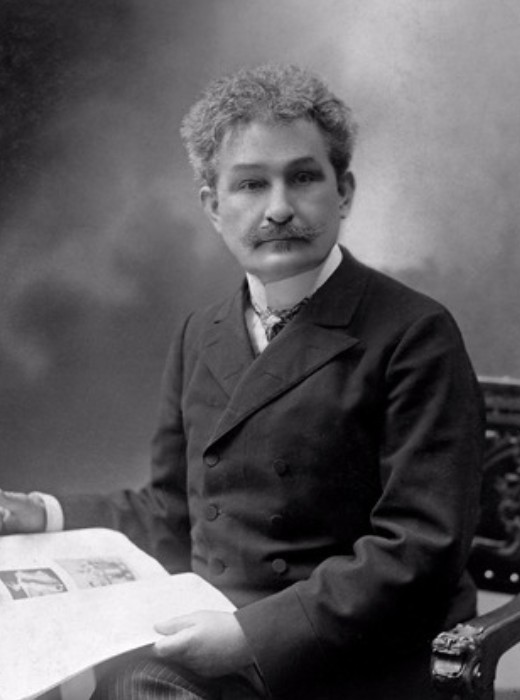

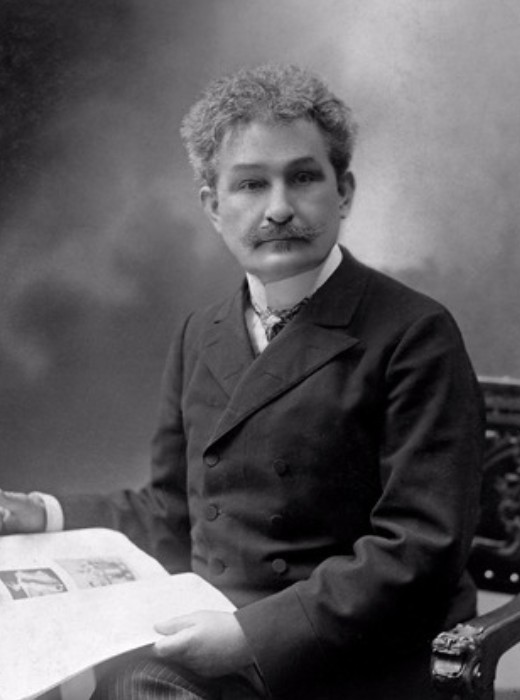

As it turns out, his marriage was just as dramatic as any of his operas.

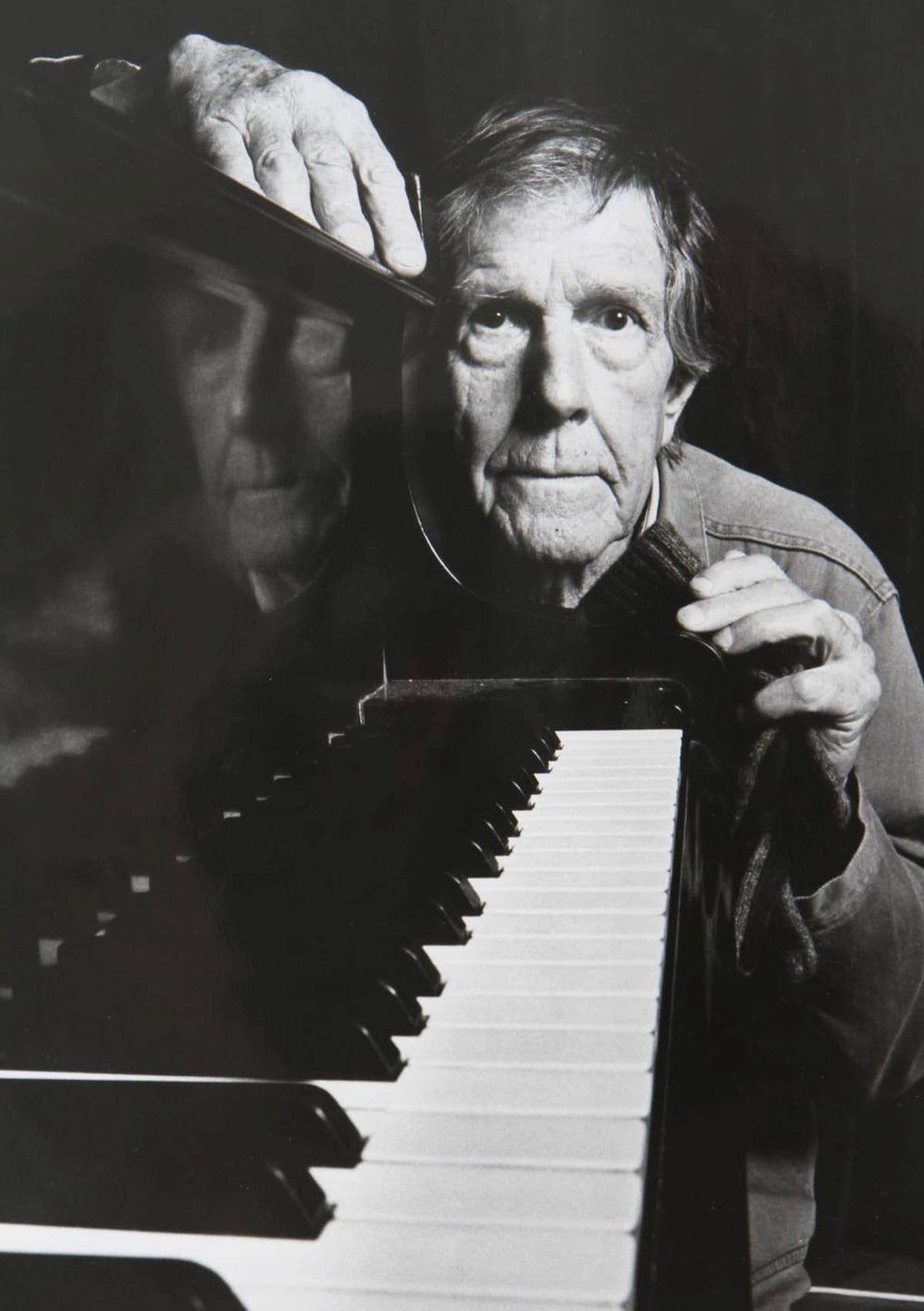

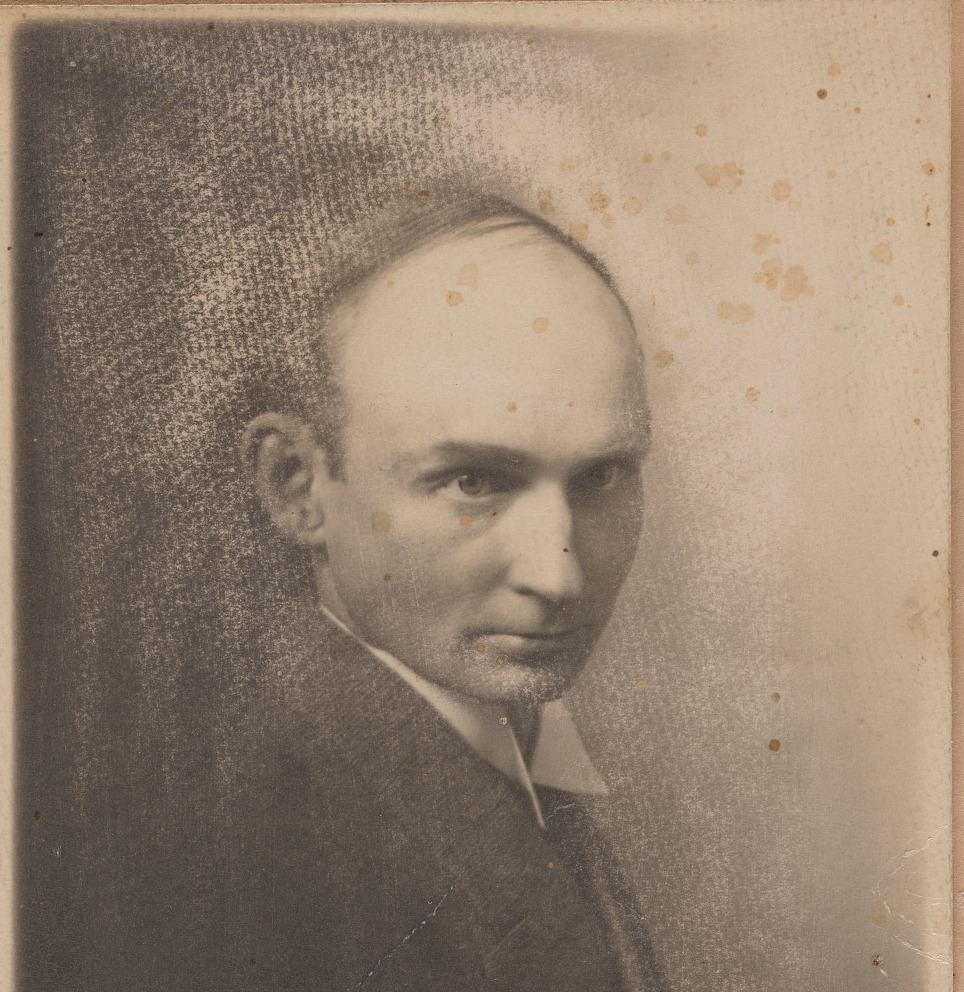

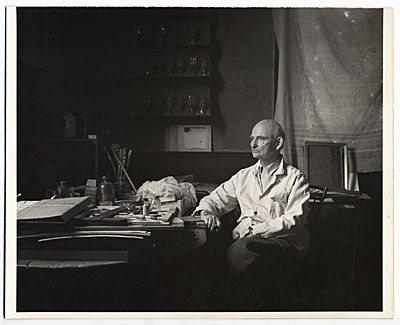

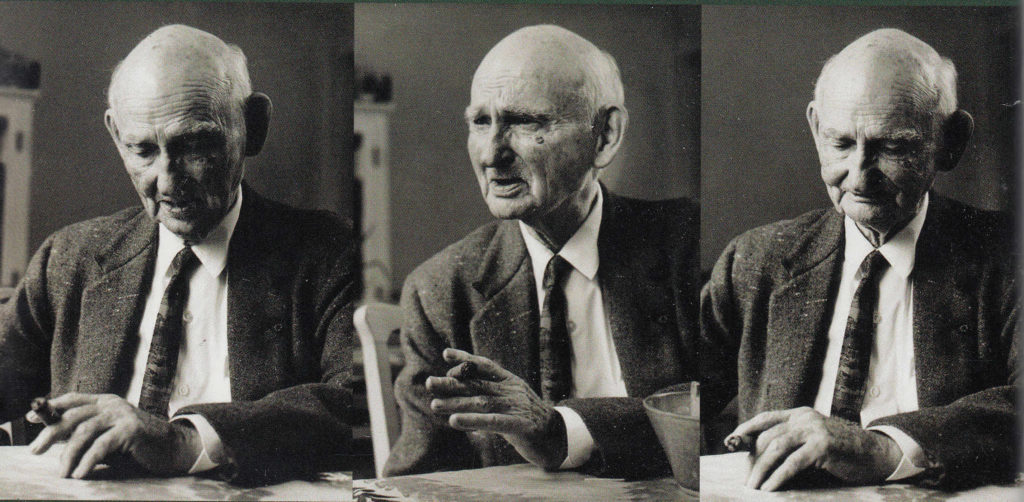

Leoš Janáček

In 1876, he began teaching piano to his future wife, Zdenka Schulzová, the very young daughter of his boss. The two later married despite a large age gap, and the relationship became a rocky one.

Their daughter, Olga Janáková, became the emotional heart of a fractured family, and her tragic early death in 1903 inspired some of Janáček’s most personal music, including the Elegy on the Death of Daughter Olga.

Today, we’re looking at the story of Janáček’s tumultuous marriage, his family struggles, and the music he wrote that was shaped by his wife, Zdenka, and daughter, Olga.

Meeting Zdenka

Brno Teachers’ Institute

In 1876, twenty-two-year-old composer Leoš Janáček began teaching music at the Brno Teachers’ Institute.

His boss, the Institute’s director Emilian Schulz, believed in his talent and had secured the teaching job for the impoverished composer.

Schulz also hired Janáček to teach his twelve-year-old daughter Zdenka piano.

The Schulzes lived in the back of the school, so Janáček would walk from the school back to their home to give her lessons.

It wasn’t long before he began taking a romantic interest in her.

During the 1879-1880 school year, he left Brno to study in Leipzig. One of the pieces he wrote there was the Zdenka Variations, inspired by his now 14-year-old piano student.

He also spent a few months at the Vienna Conservatory, but, ever prickly, hated his time there, so he returned to Brno. He proposed to Zdenka, and she accepted.

Zdenka Schulzová

In the summer of 1881, two weeks before Zdenka’s sixteenth birthday, she and Janáček were married.

The Birth of Olga

A few months later, she became pregnant with their first baby, who arrived in August 1882.

Janáček refused to be present at the birth, despite Zdenka’s wishes. In fact, he only went to see the baby after he was scolded by a priest.

They named her Olga. She would eventually become the apple of her father’s eye…but it would take a while.

The parents’ messy relationship staggered on after Olga’s birth. Janáček became increasingly focused on his flirtations and affairs with other women, ignoring Zdenka.

To her great fury, she once found him hiding a letter from a paramour. He burned the letter before she could finish reading the whole thing, but that did nothing to quell her fury.

The Janáček’s Divorce

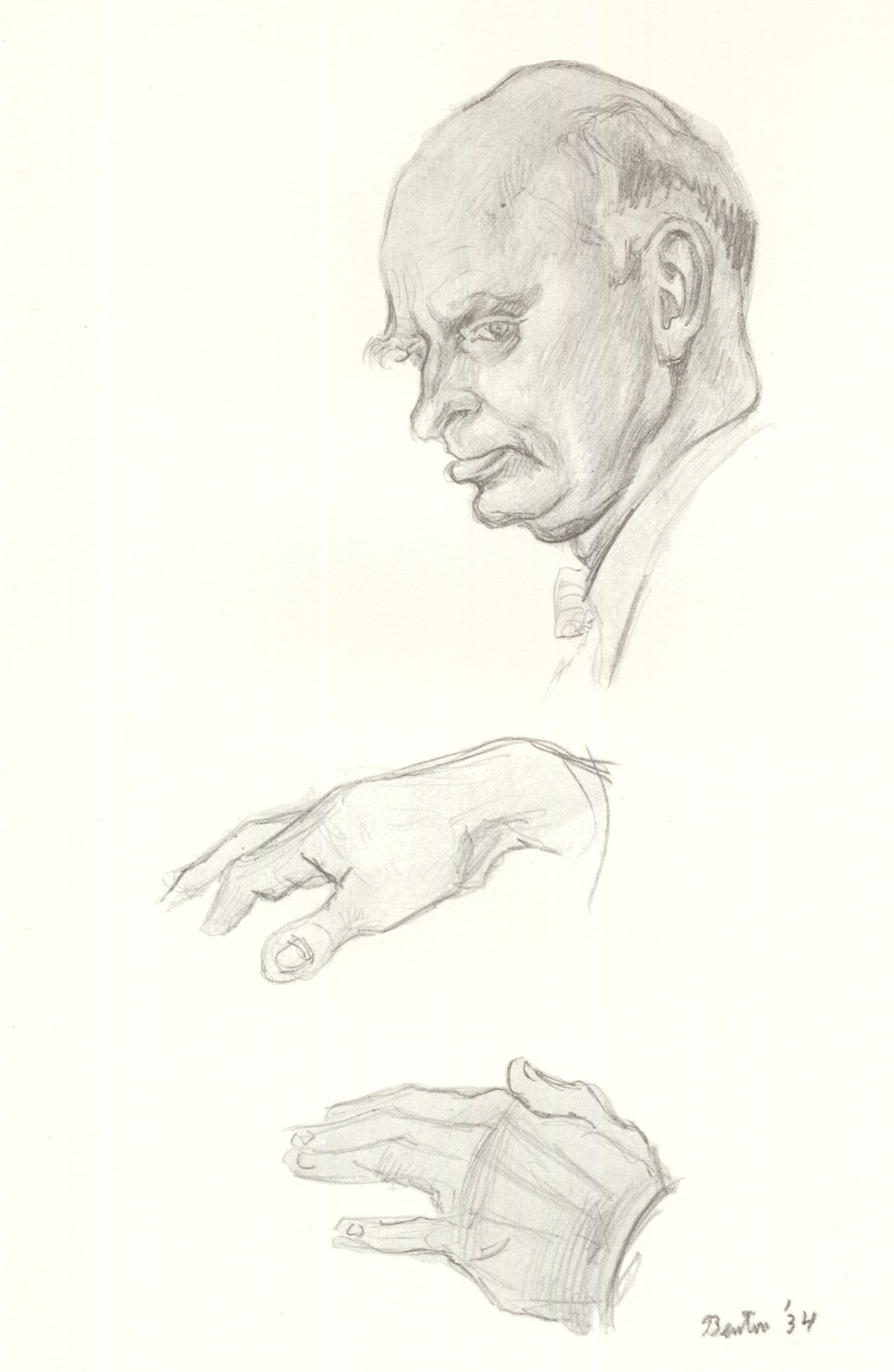

Leoš and Zdenka Janáček

Things got so bad between them that in mid-1884, they divorced.

But as soon as Zdenka became forbidden to him, the attraction reignited. He began courting her again. Thinking he had changed, she had their divorce annulled.

Vladimir Janáček

In May 1888, they had another baby, Vladimir. Zdenka later remembered that Janáček spent more time with him than he had with Olga because Vladimir was a boy.

But when both she and Vladimir grew ill, and a doctor recommended hiring a wet nurse, Janáček resorted to his old ways, refusing to pay for the expense. Zdenka’s parents chipped in instead.

The Marriage Deteriorates

Predictably, the brief separation had done nothing to address the root problems in their marriage.

According to Zdenka, Janáček hated it when she visited her parents. After she disobeyed his orders and went to see them anyway, he locked the door and left her outside while he whistled inside.

He also allowed her such a small allowance that she and the children began to starve. Once again, she had to come to her parents’ house begging.

“My husband didn’t notice anything: he never cared about how I lived and whether I needed anything,” she later wrote.

The Loss of Vladimir

Unfortunately, both Olga and Vladimir were sickly children.

Vladimir died at the age of two in 1890, devastating the entire family. Janáček was especially heartbroken by Vladimir’s loss, as he’d already started to show some signs of musical talent…which Olga never had.

Six-year-old Olga was inconsolable, crying at her brother’s casket until her face was stained with tears.

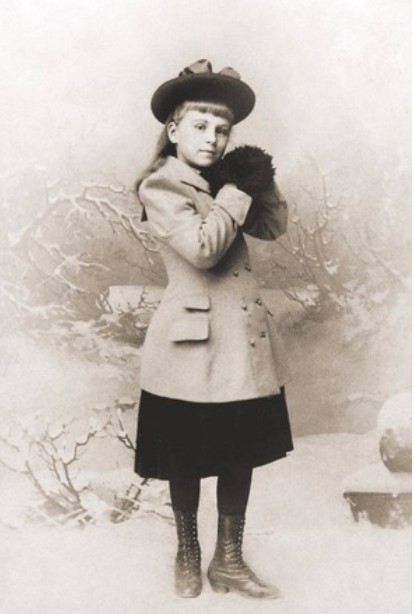

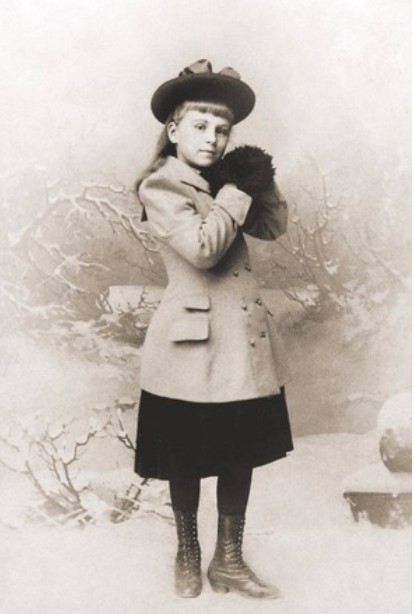

Olga Janáková

Although their relationship was falling apart again, Zdenka asked Janáček if they could have another child. He refused.

She later remembered that it was at that point that she finally lost all of her attraction to him, although there were moments sprinkled throughout the rest of the marriage where they were friends again.

Olga’s Childhood

In the year of Vladimir’s death, Olga fell ill with inflamed joints, followed by heart trouble. She endured a lot of chronic pain and was kept from many physical activities during her childhood.

Especially after Vladimir’s life and death, Olga became the emotional glue of the family.

Zdenka later wrote admiringly that Olga “grew up into a lovely girl. Her skin was delicate and smooth with a peach-bloom to it; like her father, she had a dimple in her chin.”

Although he’d been neglectful of her when she was a baby, as she grew up, Janáček gradually became closer and closer to her.

Historian Mirka Zemanová writes of Olga’s teenage years:

“By then, Olga was almost as tall as Janaček. She was slim and had inherited her father’s features and his olive complexion; like Janáček, she was a smart dresser. She had her mother’s blue eyes and long, thick, beautiful hair the colour of ‘dark gold’. Her feet were tiny, and she wore shoes just like those for Cinderella. At her school, she was an outstanding pupil; she had an excellent memory, and her surviving letters show wit and style beyond her years. Everyone seemed to love her — she was sweet-natured, generous and sincere. Yet her letters also reveal a strain of melancholy, confirmed by her photographs: there is great sweetness in her face, but a pensive look in her eyes.”

Janáček eventually bonded with Olga over her interest in the arts (she eventually became an enthusiastic amateur singer), as well as her fascination with the Russian language and Russian culture, a passion that he shared.

Olga’s Final Years

Olga Janáková

In 1900, when she was seventeen, she met a medical student at a dance, and they fell in love.

Janáček was upset. Olga (rightly) pointed out that her mother had been even younger when their relationship had begun.

Olga and the medical student were an item for quite a while until Olga began hearing “rumours about his character”, in the words of Zemanova, and she broke up with him. His response was shocking: he threatened to find her and shoot her for breaking up with him.

In response, the Janáčeks sent Olga to St. Petersburg to visit her uncle, ostensibly so she could improve her Russian, but also for her own safety. Janáček chaperoned her there in March 1902, then returned to Brno.

Unfortunately, tragedy struck during the visit: in late April, Olga came down with typhoid fever. She seemed to make a recovery, then fell ill again in June.

Both Zdenka and Janáček traveled to St. Petersburg to be with her. Zdenka stayed while Janáček returned to Brno to keep working.

She improved enough by July to travel back to Brno, but it was to be a temporary reprieve.

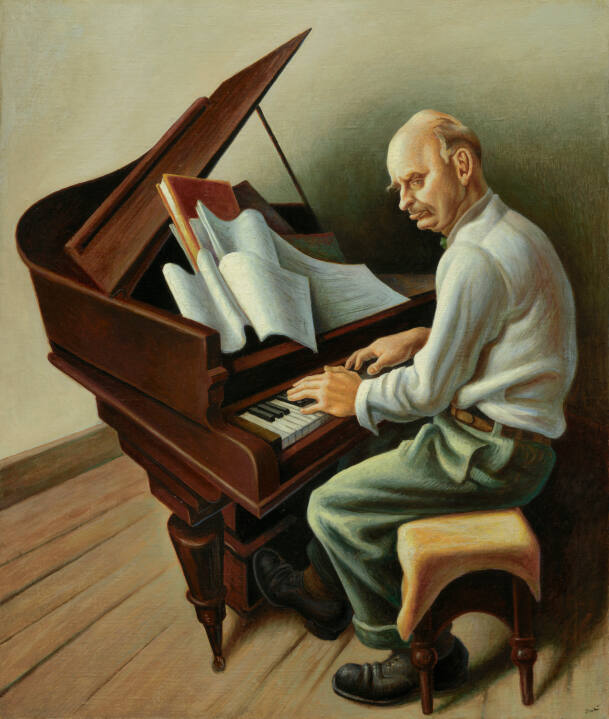

In the midst of Olga’s illness, Janáček finished his opera Jenůfa. Olga asked to hear it played on the piano, since she was convinced she wouldn’t survive to see it produced; Janáček agreed. Meanwhile, Zdenka was so upset, she went into the kitchen, unable to listen.

Janáček stayed by Olga’s bedside and, always fascinated by the “speech melodies” of others, notated his daughter’s final words and vocalisations.

“I don’t want to die; I want to live.”

“Such fear, I will resist it.”

“I’m dying; I’m dying.” (Janáček noted that she repeated this one until she became incoherent.)

He noted that his response to her was “God be with you, my darling.”

Olga died on 26 February 1903. She was just 21 years old.

The Aftermath of Olga’s Death

Olga’s death completely shattered both Janáček parents.

Janáček’s grief manifested in physical gestures. He tore at his hair and shouted, “My soul!” over and over again.

Zdenka later wrote in her memoirs:

“We stayed in our dining room alone. Abandoned, silent. I looked at Leoš. He sat in front of me, destroyed, thin, grey-haired.”

He left the final page of Jenůfa in his daughter’s coffin.

Ultimately Janáček processed the loss by paying tribute to Olga in his music. Most memorably, he dedicated the opera Jenůfa to her memory.

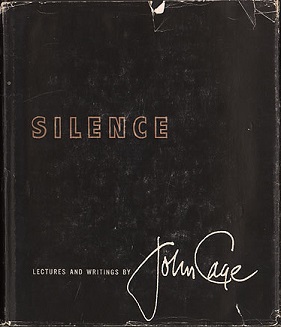

Elegy on the Death of Daughter Olga

But the music that was most pointedly about her was his 1903 Elegy on the Death of Daughter Olga.

The elegy is a cantata for tenor, chorus, and piano. He used a text by poet Marfa Veveritsa, a poet friend of Olga’s who shared the father and daughter’s love of Russian culture.

It was only premiered 27 years after its composition, two years after Janáček died.

Elegy on the Death of Daughter Olga

The Elegy isn’t often performed today, but it is a searing work that provides vitally important context to what was happening during the composition of Jenůfa, as well as the family relationships that formed Leoš Janáček as both a human and an artist.