/ robynadele

Check out all my music on your favorite platform!

https://www.robynadele.com/listen

Subscribe to my YouTube channel!

/ robynadele

Check out all my music on your favorite platform!

https://www.robynadele.com/listen

Subscribe to my YouTube channel!

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadele

/ robynadele It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

/ robynadele

Check out all my music on your favorite platform!

https://www.robynadele.com/listen

Subscribe to my YouTube channel!

/ robynadele

Check out all my music on your favorite platform!

https://www.robynadele.com/listen

Subscribe to my YouTube channel!

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadeleanderson

/ robynadele

/ robynadele by Georg Predota, Interlude

Felicia Montealegre was a stunningly beautiful Chilean stage and television actress making her living in New York. Leonard Bernstein was the wonder boy of the American classical music scene, who had made his spectacular conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic. They met at a party hosted by pianist Claudio Arrau, with whom Montealegre had studied. They were engaged a few months later, but the engagement was broken off after less than a year. The reason for the break-up of the relationship was not a secret, as Bernstein’s homosexual proclivities were undisputed and well documented.

Leonard Bernstein and his wife Felicia Montealegre, 1959

During his Harvard years, Bernstein had affairs with famed conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos and the aspiring composer Aaron Copland. And during his visit to Israel in 1948, he fell in love with the young soldier Azariah Rapoport. Bernstein writes, “I can’t quite believe that I should have found all the things I’ve wanted rolled into one. It’s a hell of an experience – nerve-racking and guts tearing and wonderful. It’s changed everything.”

Felicia was fully aware of Leonard’s sexual preferences, but she nevertheless continued to pursue him over the next three years. And Bernstein was worried that his homosexual activities would prevent him from landing a major conducting appointment. The couple married in September 1951 with the clear understanding that as long as Lenny did not embarrass Felicia publically, he was free to pursue his homosexual affairs. Despite this obvious marriage of convenience, there was a good deal of love between them. Soon after their wedding, Felicia openly writes to her husband, “If I seemed sad as you drove away today it was not because I felt in any way deserted but because I was left alone to face myself and this whole bloody mess which is our “connubial” life. I’ve done a lot of thinking and have decided that it’s not such a mess after all. First: we are not committed to a life sentence—nothing is really irrevocable, not even marriage (though I used to think so). Second: you are a homosexual and may never change—you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depends on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? Third: I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L.B. altar. (I happen to love you very much—this may be a disease and if it is what better cure?) Let’s try and see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession, please! The feelings you have for me will be clearer and easier to express—our marriage is not based on passion but on tenderness and mutual respect.”

Leonard Bernstein with his wife Felicia and his children Jamie and Alexander

The couple had three children, which led to the assumption that Bernstein was bisexual. However, according to his collaborators in West Side Story, Bernstein was simply “a gay man who got married. He wasn’t conflicted about his sexual orientation at all. He was just gay.” As was customary at that time, Bernstein appeared a devoted husband and father in the public eye, while carrying on a promiscuous homosexual life behind the scenes. It might have been a customary to hide behind a public facade, but Bernstein certainly felt that his homosexuality was a curse. He even underwent psychoanalysis from a specialist “curing homosexual men of their inversion.”

In the end, the only cure was to publicly acknowledge his homosexuality, while taking out his frustrations on his wife. Apparently, Bernstein was having sex with a twenty-year old boy in the hallway while his wife was sitting in the living room. And when he met the young Tom Cothran in 1973, he allowed his wife to catch them in bed together. By 1976, Bernstein had left his wife for his latest male lover. The very next year, Felicia was diagnosed with lung cancer and Bernstein cared for her until her death in 1978. After Felicia’s death, Bernstein gave free reign to his addiction to alcohol and drugs, and engaged in openly crude homosexual activities. Yet, he always felt guilt over how his double life had adversely affected her. He eventually gave voice to his anguish in his 1983 opera A Quiet Place, sequel to his 1951 Trouble in Tahiti. As a close family friend once remarked, “Leonard required man sexually and women emotionally.”

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

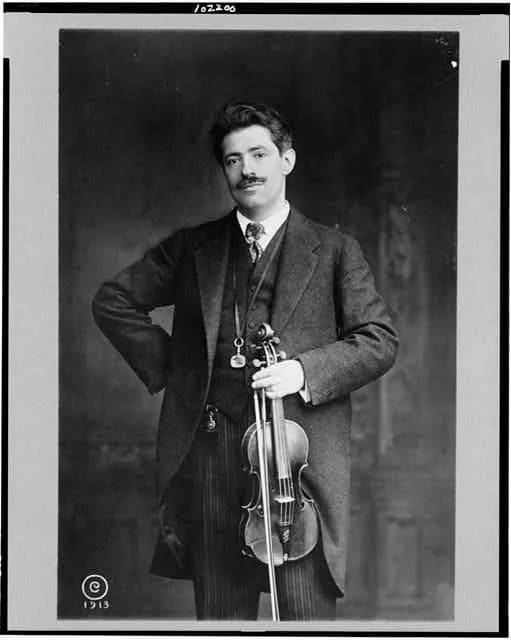

Fritz Kreisler

Let’s get started with the grandfather of all musical hoaxes, the violinist Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962). The violinist was at the vanguard of the emerging music recording industry, and he delighted audiences with performances of lost classics by famous composers. According to Kreisler, he personally discovered manuscripts of unknown compositions by Corelli, Pugnani, Vivaldi, and Couperin in a French monastery. Audiences were enchanted to hear yet another unknown masterpiece.

However, on Kreisler’s 60th birthday on 2 February 1935, the violinist unapologetically confirmed that he had been the composer all along. The music industry was outraged, but Kreisler pointed out “that it should make no difference who wrote the works as long as people enjoyed them. The name changes, the value remains.” Clearly, audiences agreed with Kreisler’s assessment as his popularity skyrocketed following the scandal.

David Popper

David Popper (1843-1913) was one of the last great cellists who played without an endpin. His tone was described as “large and full of sentiment, and his execution highly finished, and his style classical.” Popper was not only a fantastic cellist, but also a highly prolific composer. He composed four cello concertos to his name and stunned audiences at the Crystal Palace in London on 1 December 1894 with the premiere of a newly discovered cello concerto by Joseph Haydn. According to Popper, during a concert in Vienna, a man handed him a few sheets of wrinkled manuscript papers, claiming that they were sketches for a cello concerto by Haydn.

Initially, so the anecdote relates, Popper was skeptical, but a few years later he judged them to be genuine themes by Haydn. He worked them into a concert form in three movements and provided the piano accompaniment and orchestration. The Popper “Haydn” concert was published in 1899, but questions started to be raised as the original sketches could not be found. As the Musical Times wrote in 1895, “Unfortunately, the evidence adduced is inconclusive, but the concerto is decidedly pleasing in character. If not written by Haydn, it is certainly thoroughly Haydnesque both in form and spirit.” You can be the judge, as the concerto was taken up by a number of eminent cellists, including the fabulous Mstislav Rostropovich.

Marius Casadesus in 1957

The supposed musical discovery of the 20th century took place in 1933. The Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Aranyi stepped onto the London stage and performed a completely unknown violin concerto by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The performance caused an absolute sensation, and the score turned out to be an arrangement by the French violinist Marius Casadesus. Casadesus claimed that he had arranged the work from a manuscript by the ten-year-old Mozart, with a title page containing a dedication to “Madame Adélaïde de France,” the eldest daughter of Louis XV, and dated “Versailles May 26, 1766.”

Things got interesting in a hurry when scholars were not allowed to see the autograph score, and young Mozart had actually arrived in Versailles 2 days after the dedication. In addition, father Leopold Mozart did not include the work in the catalogue of his son’s works. Some people called it “a hoax ala Kreisler,” but the musical world really wanted to believe in a new Mozart concerto. As such, the “Adélaïde Concerto” was assigned a Köchel number, and Yehudi Menuhin made a famous recording. Only in 1977, during some heated litigation concerning royalties, did Marius Casadesus admit that he was the actual composer.

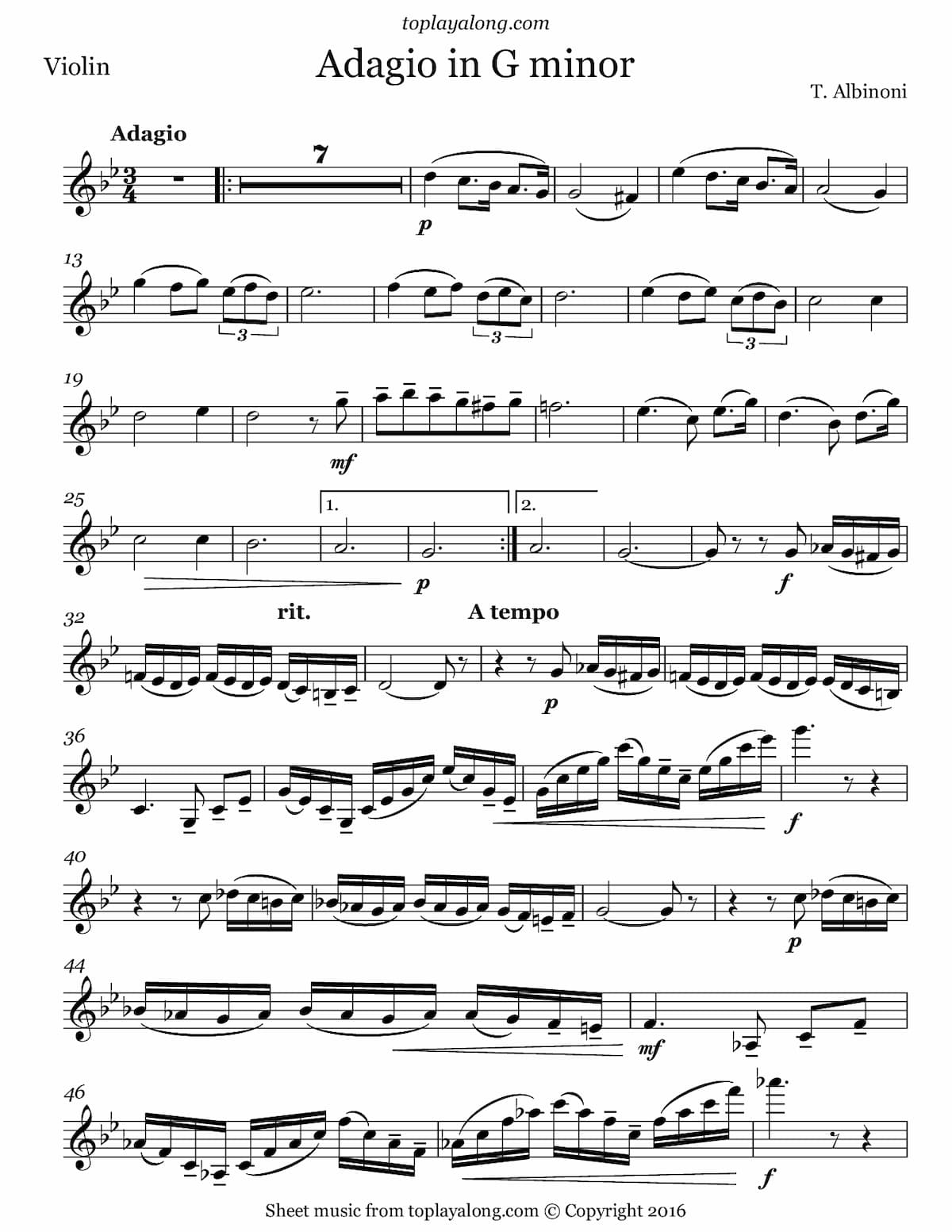

Henri Casadesus, c 1900

It’s easy to be dismissive of Kreisler’s and Marius Casadesus’ misattributions, but it is worth remembering that these “forgeries” appeared during a time when the avant-garde and 12-tone followers were aggressively shouting down the old musical system. The Casadesus family was one of the most prominent French artistic families, an integral part of the international classical music landscape. Music lovers almost certainly remember the pianist Robert Casadesus, who collaborated with Maurice Ravel. And Henri Gustave Casadesus (1879-1947), uncle of Robert and brother of Marius, had his own musical surprises ready.

Henri was a gifted violinist, and together with Camille Saint-Saëns, he founded the Society of Ancient Instruments in 1901. They performed on Baroque period instruments and introduced eager audiences to a number of unknown musical masterworks by famous masters. Henri “found” violin concertos by George Frideric Handel and Luigi Boccherini, and two famous viola concertos by Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Christian Bach. The concertos appeared in various editions and were performed and recorded by Darius Hilhaud and Felix Prohaska. It was pretty obvious from the beginning that Henri composed all those works himself, a charge he never denied.

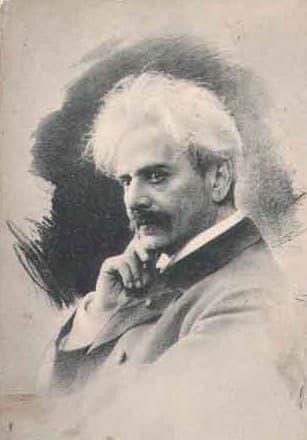

Remo Giazotto/Albinoni: Adagio in G minor

The Italian musicologist and critic Remo Giazotto (1910-1998) is not necessarily a household name. He taught music history at the University of Florence and authored studies on the music history of Genoa. Contributing to a number of music dictionaries, Giazotto also authored romanticized biographies of various composers, including Vivaldi, Viotti, Stradella, and Tomaso Albinoni. By far his most famous publication, however, was a short “Adagio in G minor” that he attributed to Albinoni.

When Giazotto was working on his biography of Albinoni in a German library, he claimed to have found a fragment of an Albinoni composition. That fragment supposedly contained snippets of a melody and a supporting continuo part. Relying on the stylistic features of the Italian Baroque, Giazotto “completed” the fragment, and the Italian publisher Ricordi published the “Albinoni Adagio” in 1958. It all sounds pretty plausible up to a point, however, the mysterious Albinoni fragment was never located or examined. Initially, Giazotto stated that he had merely arranged the work, but subsequently revised his story and claimed that it was his original composition.

Édouard Nanny

The French double bass player Édouard Nanny (1872-1942) was a long-time professor at the Paris Conservatory. He penned an important collection of pedagogical works and gained some international exposure as a composer during his lifetime, but he was really only popular in France. Among his most famous works are a Concerto in E minor, and a Concerto in A major attributed to the Italian double bass virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti (1763-1846).

The basic story is a familiar one by now. Nanny supposedly discovered a manuscript of the concerto in the British Museum Library, however, no such manuscript could ever be found. The answer to the Nanny trickery might be located in his friendship with Stuart Sankey, an important double bass pedagogue. When Sankey needed a work for double bass that could be sold quickly Nanny agreed, and he provided his Concerto in E minor under his own name. Since Nanny was not really famous as a composer, the work did not sell and the two accomplices decided to publish another concerto by Nanny, but this time attributed to Domenico Dragonetti. The “Dragonetti” concerto became immediately popular, but as you can hear, it has stylistically very little in common with Dragonetti’s music.

Winfried Michel

The German recorder player, composer, and editor of music Winfried Michel has published a number of compositions under his own name. In addition, he also published numerous pieces in the style of the early 18th century under the pseudonym Giovanni Paolo Simonetti. However, his main claim to fame was the supposed discovery of six long-lost piano sonatas by Joseph Haydn in 1993. In fact, Michel managed to convince the noted Haydn scholar H. C. Robbins Landon and Paul and Eva Badura-Skoda that an important Haydn discovery was at hand.

Supposedly, the works are based on the opening bars of six lost Haydn works, found in an old thematic index. The sonatas were published in 1995 as works by Haydn, “supplemented and edited by Winfried Michel.” “Some of the finest sonatas by Haydn,” however, turned out to be a rather clever pastiche. For a commentator in the New York Times, this raised some pretty big questions. “If these pieces are good enough to be thought to be by Haydn, then aren’t they valuable on their own terms? Or is it only because of the aura of Haydn’s authorship and historical context that they become meaningful? In which case, what is our criteria for judging the immanent qualities of musical works? Why can’t works of brilliant pastiche be as good as the “real” thing, and valued as much by musical culture.

Samuel Dushkin

The Polish-American violinist and composer Samuel Dushkin (1891-1976) initially studied at the Conservatoire de Paris, and with Leopold Auer and Fritz Kreisler. He collaborated closely with Igor Stravinsky on the Violin Concerto, and Stravinsky also composed his Duo Concertante and his Divertimento to play with Dushkin on concert tours. Dushkin also gave the premiere of the orchestral version of Ravel’s Tzigane, and William Schuman composed a dedicated violin concerto for him.

Like other violinists of his time, Dushkin published countless arrangements and transcriptions for violin and piano. As an editor and arranger, he also published a “Sicilienne for strings and clavier” by the blind Maria Theresia von Paradis, and a “Grave for violin and orchestra” by Johann Georg Benda. Most likely both works had actually been composed by Dushkin, who only took credit as the editor. The obvious motive might well have been to increase sales, and with the attribution to the lesser-known Paradis and Benda, the works certainly didn’t raise red flags as might have been the case with an attribution to Haydn or Mozart. Dushkin never admitted his authorship, so there might still be some room for discussion.

Mykailo Goldstein/Nikolay Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky: Symphony No. 21

Ukrainian-born violinist, conductor and composer Mykailo Goldstein (1917-1989) gave his first public concert performance at the age of eight, but after an injury to his left hand, he turned to teaching and composition. One of his compositions, a Fantasy on Ukrainian themes got savaged by a critic who claimed that “Jews could never understand Ukrainian culture and have no right to use it.” Apparently, Goldstein replied that Beethoven also used Ukrainian themes in his Razumovsky Quartets, to which the same critic replied “Beethoven was not a Jew.”

To prove the critic wrong, Goldstein invented the Ukrainian composer Nikolay Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky and provided him with a detailed biography. Supposedly, Kulikovsky came from an aristocratic family, and in 1809 he composed a Symphonie No. 21 in G minor, with an inscription “for the dedication of Odessa Theatre.” Goldstein announced the discovery of the manuscript, and it immediately caused a great deal of excitement in Soviet musical circles. Here, after all, was proof that the Ukraine had produced a composer comparable to Joseph Haydn. It was performed by major orchestras and conductors, and the work and fictitious composer were included in the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia. Goldstein was shocked that his hoax went undiscovered, and came forward to claim the work as his own. The initial reaction from the authorities was even more shocking, as it concluded that neither Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky nor Goldstein had written the symphony. It actually took a criminal investigation in the late 1950s to confirm Goldstein’s authorship.

Giulio Caccini/Vladimir Vavilov

Vladimir Vavilov (1925-1973) was a Russian guitarist, lutenist and composer. A student at the Rimski-Korsakov Music College in Leningrad, he was highly active as a performer, and also as a music editor of a state music publishing house. Most importantly, however, he was also an accomplished and gifted composer. Vavilov had a great sense of humour as he routinely ascribed his own works to other composers, usually masters from the Renaissance or Baroque.

Vavilov composed the “Ave Maria” around 1970, and he himself published and recorded the piece on the Melodiya label. At that point, the work was ascribed to “Anonymous.” It is generally believed that organist Mark Shakhin, one of the performers on the original Melodiya LP, first ascribed the work to early Baroque master Giulio Caccini after Vavilov’s death. In no time, the piece became a worldwide mega-hit. As to the reason for this mystification, Vavilov’s daughter Tamara explained, “My father was convinced that the self-taught works of unknown composers with the trivial name “Vavilov” would never be published. But he really wanted his music to reach the audience and he went so far as to give all the glory to medieval composers and unknown authors.”

Hugo Distler was a sensitive young man and one of the Lutheran church’s most important modernisers, and the illegitimate child of a manufacturer and a seamstress. His mother soon married (not the manufacturer) and left for America. Little Hugo was left to his grandparents and did not have a pleasant childhood. He took refuge in piano playing and took lessons in music theory and music history while at school. He later studied piano, organ and composition at the Leipzig Conservatory.

Distler concentrated primarily on polyphonic music from the renaissance and baroque periods (Schütz, Bach) and used his insights in his own compositions. He wrote these for the choirs he conducted, among others.

Distler was increasingly dealing with repression of the national socialist authorities. They had little interest in modern music (‘if I hear the word “culture”, I immediately draw my pistol,’ Goebbels seems to have once said) and religion. His work was practically declared to ‘degenerate art’ a couple of times; there were still influential colleagues who were able to hold that fatal condemntation back. They very much appreciated his compositions, and Distler got more work. In his forties he thus taught composition, organ and choral conducting in Charlottenberg and conductor of the Berlin state and cathedral Choir.

However, the workload - especially the air attacks and the hostility of the authorities, who were threatening to draft him to the army, undermined Distlers mental stamina.

He committed suicide in 1942, aged just 34, far away from the idyllic world of his love songs from the thirties.