It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, December 5, 2025

Centenary of the Premiere of the Controversial Concerto in F

by Frances Wilson December 3rd, 2025

Composed in 1925, following on the success of ‘Rhapsody in Blue’, George Gershwin’s ‘Concerto in F’ is one of the most celebrated works that straddles the worlds of classical music and jazz. Commissioned by Walter Damrosch for the New York Symphony Orchestra, it was Gershwin’s largest and most complex work for the concert stage he had yet undertaken – a fully-fledged concerto in the classical three-movement format – and the first work he scored entirely by himself, thus signalling his determination to be taken seriously by the classical establishment. The work showcases his signature blend of rhythmic vitality, blues-inspired melodies and sophisticated orchestration and, like ‘Rhapsody in Blue’, it captures the energy and spirit of 1920s America, from bustling urban life to lyrical introspection. It stands as a landmark in American music, demonstrating Gershwin’s ability to fuse popular idioms with symphonic tradition.

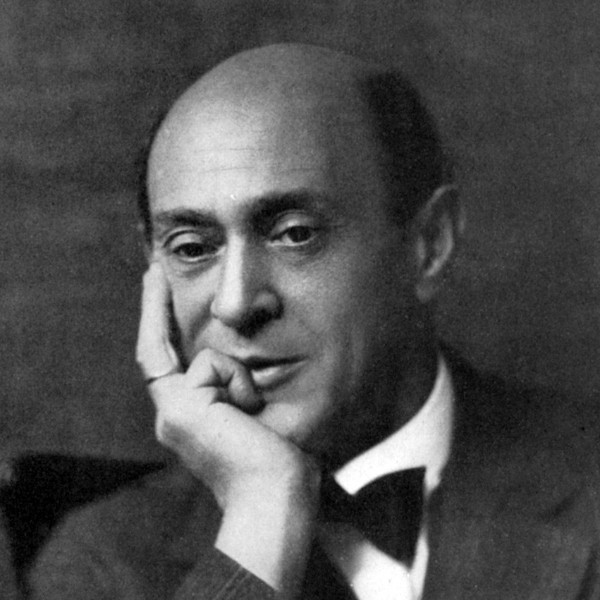

George Gershwin

‘Many persons had thought that the Rhapsody [in Blue] was only a happy accident. Well, I went out, for one thing, to show them that there was plenty more where that had come from’ – George Gershwin speaking about the birth of his Concerto in F.

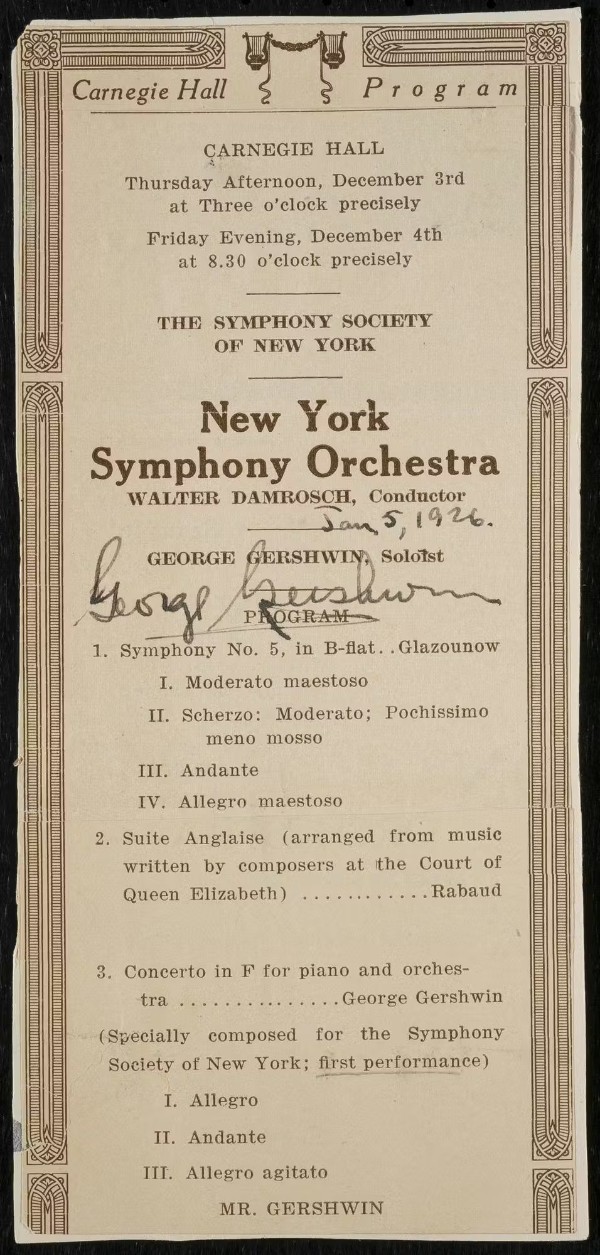

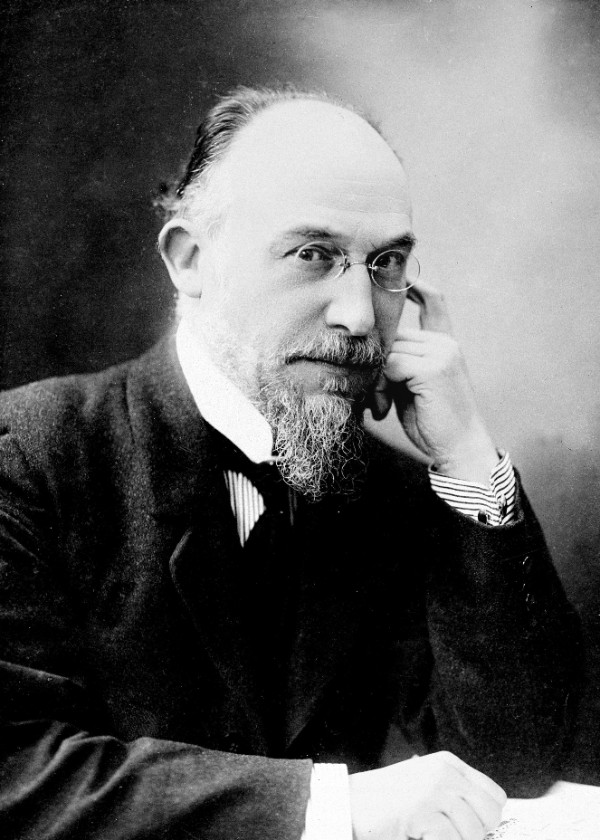

The Concerto’s premiere took place at Carnegie Hall on 3rd December 1925, conducted by Damrosch with Gershwin at the piano. The concert was sold out, and the Concerto was very well received by the general public. But the reviews were mixed, with many critics unable to classify it as jazz or classical. There was a great variety of opinion among Gershwin’s contemporaries too: Prokofiev found it “amateurish”, while The New York Times called it “a new kind of symphonic jazz,” acknowledging Gershwin’s growing maturity as a composer beyond the success of his earlier ‘Rhapsody in Blue’. Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most influential composers at the time, praised Gershwin’s concerto in a posthumous tribute in 1938:

Arnold Schoenberg

‘Gershwin is an artist and a composer – he expressed musical ideas, and they were new, as is the way he expressed them.… Serious or not, he is a composer, that is, a man who lives in music and expresses everything….by means of music, because it is his native language. … What he has done with rhythm, harmony and melody is not merely style. It is fundamentally different from the mannerism of many a serious composer [who writes] a superficial union of devices applied to a minimum of ideas. … The impression is of an improvisation with all the merits and shortcomings appertaining to this kind of production. … He only feels he has something to say and he says it.’

The concerto’s lasting legacy begins with its role in legitimising jazz as a component of “serious” music. Gershwin didn’t simply sprinkle jazz harmonies over a classical structure: instead, he successfully integrated syncopations, bluesy melodic contours and the raw energy of urban life into the concerto’s DNA. This helped shift attitudes in concert halls, expanding the notion of what orchestral music could or should contain. It also paved the way for later composers such as Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland to continue exploring the crossover between jazz and classical idioms.

Carnegie Hall program

In addition to its historical importance, the Concerto in F is a beloved staple of the piano concerto repertoire because of its sheer musical appeal. Pianists relish its virtuosic demands, from crisp syncopations to sweeping, lyrical lines. Orchestras enjoy its colourful writing, which includes inventive writing for percussion and dynamic interactions between soloist and ensemble. And audiences continue to be captivated by its buoyant spirit and its ability to convey both exuberance and introspection. Few works capture the optimism, swagger, and complexity of early 20th-century America as vividly as the Concerto in F.

Frédéric Chopin and George Sand: The Real Story Behind Their Relationship

by Emily E. Hogstad November 15th, 2023

It’s one of the most romanticized love affairs in music history: dashing cross-dressing woman novelist George Sand becomes obsessed with, and then seduces, the sickly consumptive pianist-composer Frédéric Chopin.

But how much of this story is real, and how much of it is just mythologizing?

Today we are looking at the real story behind the love affair between George Sand and Frédéric Chopin.

George Sand’s Childhood and Marriage

George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil was born on 1 July 1804 in Paris.

As a girl, she lived with her grandmother at the family manor house in Nohant, roughly three hundred kilometers from Paris.

In 1821, her grandmother died, and Aurore inherited the manor. The house at Nohant became a home base for her throughout her life.

In 1822, at the age of eighteen, Dupin married a man named Casimir Dudevant, whose biggest accomplishment in life ended up being George Sand’s ex.

They had two children together: a son named Maurice in 1823 and a daughter named Solange in 1828. (That said, Solange’s paternity is questioned.)

After almost a decade, the marriage deteriorated. Mrs. Dudevant left her husband in 1831 and, scandalously, began seeing other men. In 1835, she separated from him legally and took custody of her two young children.

George Sand’s Writing Career

In her twenties, the former Mrs. Dudevant embarked on romantic relationships with a wide variety of accomplished artistic men, including novelist Jules Sandeau, writer Prosper Mérimée, dramatist Alfred du Musset, and others. (She also developed intense romantic feelings for actress Marie Dorval. The two would remain friends for the rest of their lives.)

The former Mrs. Dudevant’s writing career began in the early 1830s, when she began collaborating on stories with her lover Jules Sandeau. They signed their joint efforts “Jules Sand.”

It quickly became obvious that she was a very talented writer. In 1832, at the age of twenty-eight, she wrote a novel on her own and published it under the pseudonym George Sand.

It wasn’t long before this divorced mother of two was one of the most respected authors in Europe. Her work was actually more popular in England than either Hugo’s or Balzac’s!

As her career progressed, she didn’t restrict herself to just novels: she also wrote literary criticism, theatrical works, political commentary (she was a socialist), and more.

The Meeting of George Sand and Frédéric Chopin

Josef Danhauser: Franz Liszt Fantasizing at the Piano

Apparently, Sand was intrigued by Chopin even before they met. It is believed she encouraged their mutual friend Franz Liszt to arrange an introduction.

On 24 October 1836, in the salon of fellow author (and Liszt’s mistress) Marie d’Agoult, George Sand and Frédéric Chopin met each other for the first time.

Chopin was initially repulsed by Sand, reportedly asking Liszt, “Is she really a woman?”

Despite this rocky first impression, Sand still remained intrigued by him.

It seems they were not close before 1838. In May of that year, she asked a mutual friend in a letter if he was still engaged (at one point, he had been betrothed to his former pupil Maria Wodzińska). If so, Sand wrote, she would back off. However, it turns out that the relationship with Wodzińska was well and truly over.

It’s unclear exactly how, but eventually Chopin and Sand became friends, and then lovers.

Their Trip to Majorca

To celebrate their new partnership, Sand planned a trip to Majorca, Spain, over the winter of 1838. She was hopeful that the change in climate would help Chopin’s declining health.

The trip started off on a high note. “The sky is like turquoise, the sea is like emeralds, the air as in Heaven,” he wrote in a letter.

Chopin ended up composing some of his best-known works in Majorca, including his 24 Preludes. The work tied most closely to this place in time is undoubtedly the Raindrop Prelude, said to be inspired by the rain dripping off the eaves of their lodgings.

The trip became a struggle when, as the Raindrop Prelude suggests, the winter weather turned damp. Instead of improving, his health deteriorated. The couple’s gloomy accommodations didn’t help matters: they had sought refuge in a deserted monastery in Valldemossa.

Soon Catholic locals began viewing the unmarried divorcée and her invalid partner with suspicion. The couple’s reputation grew even worse when rumors spread that Chopin’s cough would spread communicable disease. In the end, the locals grew so impossible to work with that Sand was eventually forced to lug a handcart to the capital city of Palma just to load up on basic supplies.

Their nightmare came to an end ten weeks after they arrived, but unfortunately their return voyage to Barcelona occurred during rough seas, and Chopin suffered from seasickness on the way home.

Life in France

Portrait of Frédéric Chopin and George Sand by Eugène Delacroix

A much more agreeable destination turned out to be Sand’s country home in Nohant. Chopin and Sand settled into a schedule of spending half the year in Nohant and the other half in Paris (albeit in separate apartments).

Although they never officially moved in together full-time, in 1842, they did take the step of renting adjacent apartments.

Chopin ended up writing many great works at Nohant. Today the home is a museum.

The Breakup

So why did these two titans of the Romantic Era break up?

One blow was Sand’s novel Lucrezia Floriani, which starred a sickly Eastern European prince being cared for by Lucrezia, the protagonist. The Polish Chopin grew increasingly resentful of this particular creative choice, feeling that his health troubles had become nothing but grist for Sand’s creative mill.

A second blow came when Chopin sided with Sand’s daughter, Solange, in various fierce mother-daughter arguments. Sand interpreted Chopin’s loyalty to Solange as his being in love with her. It didn’t help matters that Sand’s other child, Maurice, didn’t like Chopin, either.

Ultimately, after almost a decade together, the two great artists split up for good.

On July 28, 1847, Sand wrote to him: “Goodbye, my friend. May you soon be cured of all your ills, as I hope that now you may be…. If you are, I will offer thanks to God for this fantastic ending of a friendship which has, for nine years, absorbed both of us. Send me your news from time to time. It is useless to think that things can ever again be the same between us.”

Backlash to the Breakup

Sand herself predicted the backlash that would come: “His own particular circle will, I know, take a very different view [of the breakup],” she wrote. “He will be looked upon as a victim, and the general opinion will find it pleasanter to believe that I, in spite of my age, have got rid of him in order to take another lover…” Her predictions about public opinion turned out to be cannily accurate.

It’s also noteworthy that their relationship is often boiled down – wrongly – as one between nurse and caretaker. In his own writings, Liszt, for whatever reason, enjoyed emphasizing Chopin’s weakness and medical troubles, and therefore Sand’s role as his patient helper. However, Sand seemed to chafe against the idea. The relationship was simply more complex than that. She wrote of the Majorca disaster, “It was quite enough for me to handle, going alone to a foreign country with two children…without taking on an additional emotional burden and a medical responsibility.”

Sand and Chopin’s Final Meeting

Both Chopin and Sand left accounts of their final meeting. Comparing them is fascinating.

“I saw him again briefly in March 1848,” Sand wrote in her autobiography. “I clasped his trembling, icy hand. I wanted to talk to him; he vanished. It was my turn to say he no longer loved me.”

Chopin, on the other hand, wrote a longer account in a March 1848 letter to Solange: “Yesterday… I met your Mother in the doorway of the vestibule….” He asked whether Sand had any news about Solange, and let Sand know that Solange had had a baby, since mother and daughter weren’t on good terms at the time. He “bowed and went downstairs.” Then he decided he had more to say, so he asked a servant to bring her to him again. They talked some more. “She asked me how I am; I replied that I am well, and asked the concierge to open the door.”

Chopin died a little more than a year later. Sand opted not to attend his funeral. She lived many more years and wrote many more books.

Despite that tragic end to their love affair – or maybe because of it – George Sand and Frédéric Chopin remain one of the most iconic couples of the Romantic Era.

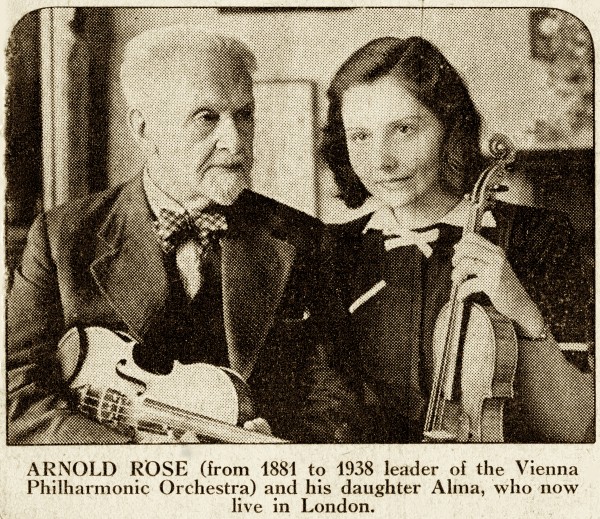

From Musical Royalty to Tragic Heroine Violinist and Conductor Alma Rosé

Alma Rosé

Alma Rosé, a top-class artist – violinist, conductor, ensemble leader and actress, is most remembered today for her amazing courage. She was the conductor and founder of the celebrated women’s orchestra Wiener Walzermädeln–but she is primarily remembered as the conductor of the infamous women’s orchestra in the Nazi death camp Auschwitz. While she kept her musicians alive, she tragically perished.

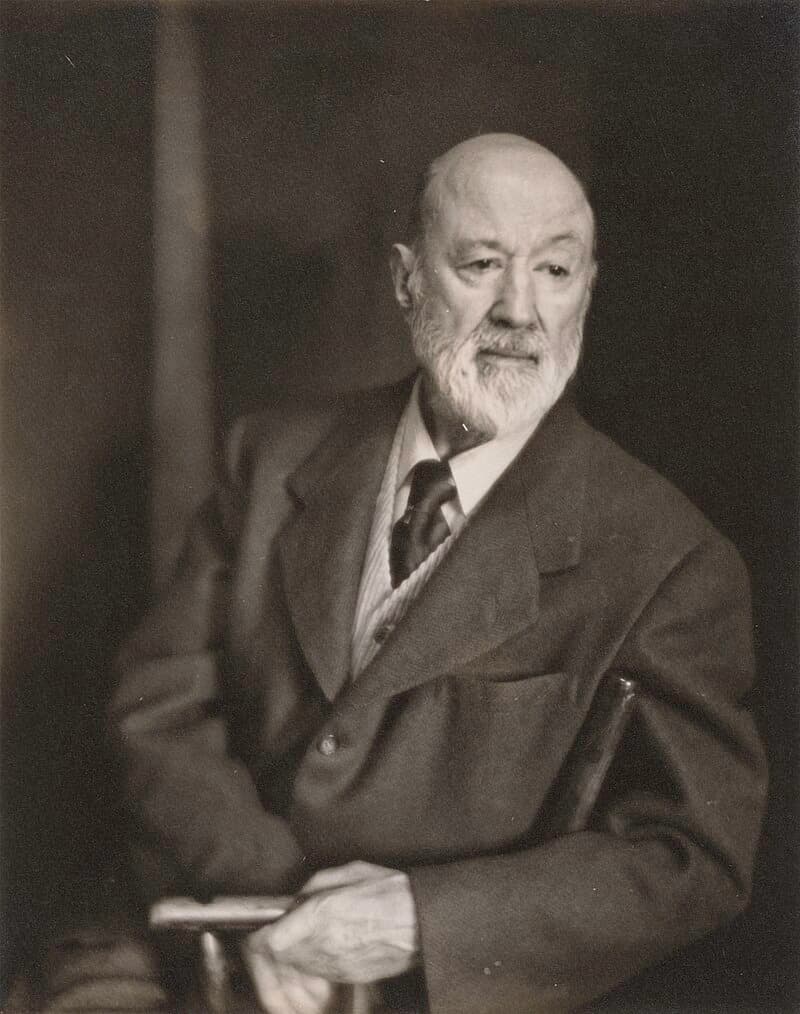

Gustav Mahler

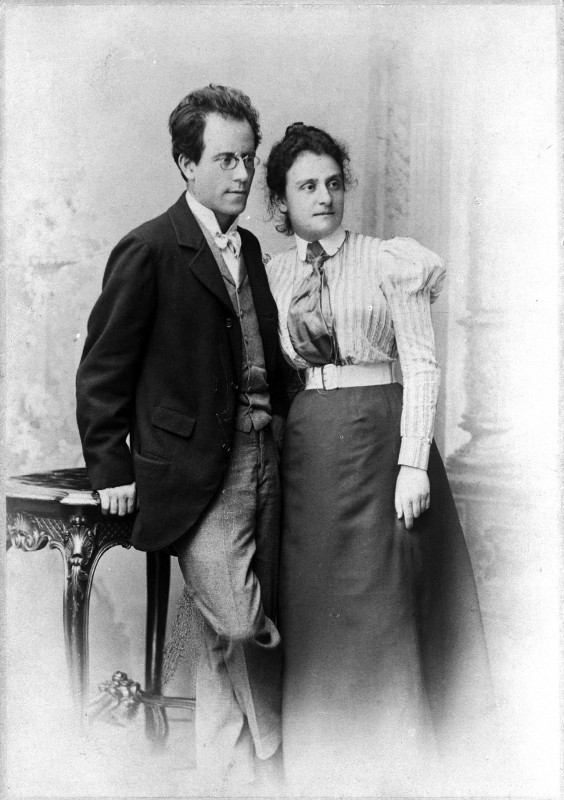

Justine and Gustav Mahler

Alma came from musical royalty: Alma’s mother, Justine Mahler, was the younger sister of legendary composer Gustav Mahler. As Mahler’s niece, she had contact with and was surrounded by the musical stars of early 20th-century Germany and Vienna. Her father, violinist Arnold Rosenblum, also a great influence, was the concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic.

Gustav Mahler and Arnold Josef Rosé

To be accepted in Vienna into the upper echelons of society, it was not advantageous to be Jewish. Rosé Austrianized his name from Rosenblum to Rosé in 1882. Mahler also felt he had to convert, and he did so in 1897 to Catholicism.

The young Alma Rosé

Rosé, a superb violinist, founded and performed with the internationally renowned Rosé String Quartet. The Rosé quartet gave premieres of both Brahms and Schoenberg. That’s an indication of the group’s longevity, and we are fortunate to have a recording from 1910, albeit a bit scratchy!

Alma and Arnold Rosé, Date unknown © Gustav Mahler–Alfred Rosé Collection, Music Library, Western University, London, Canada

Arnold was Alma’s first teacher, and soon Alma was proficient enough to make her Viennese debut in 1926, at the Musikverein, playing Bach‘s Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043 as a soloist performing with her father. We can hear them together playing the Largo movement on this rare recording from 1928. There are no other known sound recordings of Alma.

In 1930, at the age of 24, Alma married the brilliant young Czech violinist Váša Příhoda and took Czechoslovakia citizenship. Alma hoped to stand out from the shadow of the two great violinists in her life, her father and her husband. She established something different, founding a touring women’s orchestra in 1932. The nine to fifteen-member Wiener Walzermädeln (Viennese Waltzing Girls) donned elegant and feminine matching gowns, sometimes wearing charming caps, and played the most popular music of the time, the Viennese waltz. Austria had become synonymous with the waltz, a popular genre in the 1800s and homeland of the Waltz King, Johann Strauss II. The Walzermädeln toured with enormous success all throughout Europe in the early 30s.

The Viennese Waltz Girls (Bottom: Alma Rosé standing) 1933

© Gustav Mahler–Alfred Rosé Collection, Music Library, Western University, London, Canada

Alma Rosé as a young girl around 1914 © Gustav Mahler–Alfred Rosé Collection, Music Library, Western University, London, Canada

The music they would’ve played includes Johann Strauss’s charming waltzes, marches, and polkas such as Artists Waltz Op.316, his Persian March Op. 289 and his Champagne Polka Op. 211.

The group continued to perform all over Europe, from Warsaw to Rome, until the political climate in Austria became increasingly alarming, when Hitler came to power in Germany. The last concert of the Viennese Waltzing Girls was at Vienna’s Ronacher Theater on New Year’s Eve 1937, bringing their performances to an end. Only a few weeks later, the Nazi “Anschluss” (annexation) of Austria took place in March 1938. The Rosé family members were immediately barred from performing. Alma’s father, after 57 years, was removed from positions at both the Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic, ignominiously ousted.

As Jews, the Rosé family understood the serious risks to their family. During the troubling years of the 1930s, they’d felt helpless, as Alma’s mother, Justine, Mahler’s sister, was gravely ill. When she died in the late summer of 1938, they began to formulate a plan to escape.

Alma’s brother Alfred and his wife Maria Rosé-Schmutzer fled shortly afterwards, a complicated getaway via the Netherlands, then by ship to New York, finally arriving in London, Ontario, Canada.

Alma stayed behind to care for her father. Here is an extraordinary documentary to listen to.

By April 26, 1938, the Regulation on the Registration of the Assets of Jews was put into place. All Jewish people, as well as non-Jewish partners in so-called Mischehen (mixed marriages), were forced to declare their assets if they exceeded RM 5,000. The Rosé family, prominent members of society, were targeted by the Nazis. What would become of their violins? Arnold owned a rare 1718 Stradivarius and Alma, an exquisite Guadagnini from 1757.

Alma and Arnold Rosé with their violins, Atelier Willinger, undated © KHM-Museumsverband, Theatermuseum

Alma couldn’t risk the confiscation of the violins by the Nazis, but to conceal such valuable assets was a huge risk, especially for well-known personalities. It would require courageous action, clear-headed thinking, and a foolproof scheme to save them.

Undaunted, Alma’s declaration listed both violins, but their pedigree was cleverly hidden. She filled out the required document, “two Italian violins for personal use”, without the names of the makers of the instruments, which would have immediately revealed their value.

The ploy worked. It helped enormously that Alma’s Czech married name and her Czechoslovakian citizenship disguised who she truly was, a critical factor that contributed to a successful flight from the Nazis.

Alma fled to London in early 1939. Arnold followed her a few weeks later at the last possible moment before the borders were tightly closed. After such an incomparable and illustrious career, Arnold was forced to leave Austria penniless.

Once they’d escaped, they were plagued by financial problems that became overwhelming. The refugees flocking to London, mainly European musicians, were barred from performing and teaching. Alma succeeded in taking both instruments with her, but as hunger became a constant, the Rosés adamantly refused to sell their violins.

In desperation, Alma signed a contract for a two-month engagement at the Grand Hotel Central in The Hague – a venue where she and the Wiener Walzermädeln had performed with great success. Alma played several house concerts and extended her stay as additional engagements opened up for her in the Netherlands.

For a few months, she was able to resume her successful concert life. But the Germans occupied the Netherlands in May of 1940. The enemies were once again at her heels. Alma and Příhoda had divorced in 1935, and she’d married Constant August van Leeuwen Boomkamp, a medical student, to continue to evade detection.

It didn’t help Alma. This time, she was trapped. Alma was arrested at a train station in France and sent to Drancy for several months. Established in August 1941, the Drancy camp in France became a major transit camp for the deportations of Jews from France. Almost 65,000 Jews were deported from Drancy to terrifying destinations, including Auschwitz. Fewer than 2,000 of them survived.

On July 18, 1943, Alma was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Almost immediately, she was sent to the dreaded and horrifying medical experimentation block—Block 10. She’d been registered under her husband’s name, so once again, Nazi officials did not realise who she was.

Fortuitously, a request was made for a violinist for a VIP’s birthday celebration in the camp. The Nazis, after all, loved their music. She played for them, and her virtuosity quite impressed the officials.

They transferred Alma to Birkenau and, in August 1943, selected her to be the conductor of the women’s orchestra.

Alma seemed to have no fear of the SS guards who respected her musicianship. Taking advantage of her position, Alma requested and somehow managed some privileges.

Her orchestra received a special barracks, which contained an unheard-of living and practicing area, with a small heater. The dwelling even had a wooden floor! Alma convinced the authorities that the instruments had to be protected against the cold and dampness. Downright luxurious compared to the bare barracks of others.

Alma began to work tirelessly on the ensemble’s quality. The group was made up of mostly amateurs who played a wide array of instruments, including violin, accordion, flute, guitars, and mandolins. Alma endeavoured to keep the players with less talent on as assistants rather than dismissing them, which was a life-saving gesture in the context of Auschwitz.

Rosé was a strict and thorough taskmistress, pushing her musicians to the limits of their endurance. It was paramount to do everything she could to make them sound professional, because the Nazis knew their music. Alma couldn’t risk mediocrity. The women rehearsed daily for eight hours a day, thereby evading the slave labour workforce.

The SS required the orchestra to play daily at the camp gates as prisoners departed for and arrived from slave labour morning and evening, and when captives were marched to the crematoriums.

The Auschwitz orchestra also performed regular Sunday concerts for selected prisoners and the camp staff; they made regular visits to the infirmary, played during elite visits to the camp, and had to be available for individual SS demands like birthday parties.

Although Alma drove herself and the musicians, she was respected by her orchestra, valued for both her violin playing and her conducting. Above all, she understood that if they were to survive, they had to please the SS. Surely, if they played well enough, they would be allowed to live.

Drawing of Alma Rosé in Auschwitz

Rosé arranged pieces for her orchestra from whatever sheet music she had available and from melodies she recalled from memory: music by Mozart, Schubert, Vivaldi, Johann Strauss, and Franz Liszt, and from German hits, movie and operetta tunes.

Playing music gave them all moments of respite, allowing them to float somewhere above or beyond the camp atmosphere.

Alma Rosé’s final concert was at a private SS party on April 2, 1944.

Suddenly and inexplicably ill, she was taken to the infirmary with head and stomach pains and a high fever. On 4 April 1944, she was declared dead. There are still questions about her death. Could it have been suicide or poisoning by jealous functionaries? Many insist that she fell victim to accidental food poisoning or a sudden infection.

Unbelievably enough, the SS approved an observance in her memory —to recognise her unique status, perhaps the only time in the history of the camps that SS officers honoured a dead Jewish prisoner.

For the musicians, however, their grief was mixed with fear. Former member Silvia Wagenberg remembered:

When she died, I thought, now it’s over; either they will send us somewhere else — then we’re done for, or we’ll be gassed right away. It is hardly measurable what Alma meant for the orchestra.”

All but two of the orchestra members survived the war. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a cellist, was one of them, saved by playing in the Auschwitz women’s orchestra.

When the war was finally over, Lasker-Wallfisch settled in Britain, where she met and married her husband, Peter Wallfisch. She was the founding member of the British Chamber Orchestra, touring internationally with the group. Anita refused to go to Germany for many decades until in 1994, she realised she must relate her experiences during the war.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, now 100 years old. She has eloquently related her experiences in numerous documentaries about her life. Two poignant things she’s said jump out for me: “As Long as We Can Breathe, We Can Hope,” and “Music takes you out into a different sphere. You get away from your horrible realities…You could lose yourself in music, untouchable.”

Please listen to two short examples of Lasker-Wallfisch’s testimonies.

The piece that is featured in this clip by the BBC, Robert Schumann’s Träumerei is ironically enough, from his “Scenes from Childhood”, this movement is entitled “Dreaming.”

It is deeply troubling that Alma perished alongside so many millions. It’s impossible to imagine that under these horrific circumstances, musical ensembles were established in several concentration camps, including an orchestra that my father joined after being liberated. Somehow, the musicians continued to perform, and music saved their lives.

Even after the war, music enabled survivors to build a new life. My father was one of them. A cellist too, after months as a slave labourer in the copper mines of Bor, Yugoslavia, my father played 200 concerts from 1946-1948 in a 17-member orchestra in the displaced persons camps throughout Bavaria. Their mandate—to bring morale-boosting programs to those still languishing in DP camps waiting for news of loved ones or the right paperwork to leave Europe. In 1948, two of the concerts my father played in Landsberg, Germany, were with Leonard Bernstein performing and conducting, before he was as famous as he was to become.

If you’d like to read more about these times, I tell our family story in my book The Cello Still Sings – A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music.

There’s a wonderful book about Alma Rosé by Richard Newman, Alma Rosé: Vienna to Auschwitz, and watch for a new documentary now in production, Alma Rosé, directed and produced by Francine Zuckerman of z films. (More details from @almarosefilm)

Eight Pieces of Classical Music With the Weirdest Names

Most people think of classical music as being very serious. But in reality, classical music is often bizarre, sarcastic, or just plain weird.

Today, we’re looking at eight compositions with particularly weird titles, from Mozart’s cheeky “Leck mir den Arsch” to La Monte Young’s “Composition 1960 #7: to be held for a long time.”

We’re also looking at the fascinating stories behind them.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Leck mir den Arsch fein recht schön sauber (Lick my Arse for Six Voices) (ca. 1782)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart loved two things especially dearly: composing and scatological humour.

In fact, so much scatological humour appears in his letters that some scandalised editors of his correspondence actually scrubbed it from their editions!

Occasionally, his sense of humour boiled over from his letter-writing into his compositions, like in his three-part canon “Leck mich im Arsch”, which was likely meant to be a silly party song for his friends.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Translated to English, the expression “Leck mich im Arsch” means something equivalent to “kiss my ass.”

It’s a phrase that has no right to be arranged so cleverly or to sound so good…which of course is part of the joke!

Charles-Valentin Alkan: Funeral March on the Death of a Parrot (1859)

Composer Charles-Valentin Alkan is one of the most intriguing figures in classical music history.

He was a piano prodigy born in 1813 who, in the 1830s, was often mentioned in the same breath as Chopin and Liszt.

Charles-Valentin Alkan

However, after Alkan had a son out of wedlock in his mid-twenties, he withdrew from the concert stage for a time. He resumed his performing career in the mid-1840s. But after losing a prestigious job at the Paris Conservatoire and the devastating early death of Chopin, Alkan withdrew from public life again, focusing on studying and composing.

In 1859, Alkan wrote this parody funeral march, drawing from the pompous tradition of grand opera. It was composed for four voices, three oboes, and one bassoon.

The lyrics translated are “Have you eaten, Jaco? And what? Ah!” This is the French equivalent of the English expression “Polly wants a cracker?”

Alkan takes himself so seriously that if you just heard the music alone, you’d never guess the gentle, winking absurdity of the premise.

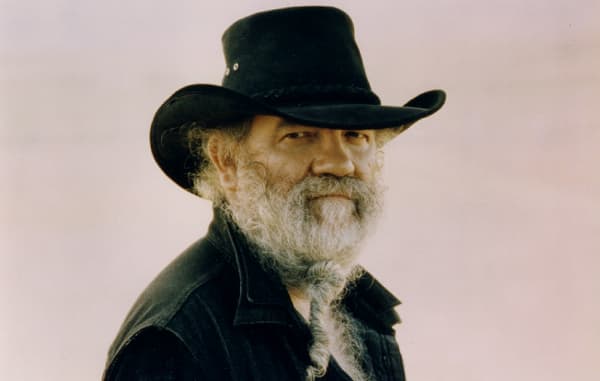

Erik Satie: Trois morceaux en forme de poire (Three Pieces in the Form of a Pear) (1903)

Composer Erik Satie specialised in absurdity, and his four-hand piano suite “Trois morceaux en forme de poire” offers absurdity in abundance.

The first joke is that, despite the title, the suite consists of seven pieces, not three.

According to legend, the “pear” part of the title originated with a criticism Claude Debussy leveled at Satie: namely, that Satie didn’t pay enough attention to form.

Erik Satie

Satie then chose a deliberately absurd shape so he could answer any criticism by Debussy by saying, “but it’s in the form of a pear!”

In France, pears also have a cultural connotation with the archetype of a fool or simpleton, meaning the joke may have been on Debussy, Satie himself, or maybe both!

Alexander Scriabin: The Poem of Ecstasy (1905-08)

Composer Alexander Scriabin believed that his life’s mission extended far beyond writing music.

In 1903, he began writing a work called Mysterium, which he continued working on for over a decade, until his death.

Alexander Scriabin

He wanted to stage a performance of it during a weeklong festival in the foothills of the Himalayas, after which he believed the end of the world would come, and human consciousness itself would shift.

In 1905’s The Poem of Ecstasy, we get a taste of his intense conviction and creative energy in a work that was actually finished. The narrative of the Poem follows a spirit achieving consciousness.

Scriabin wrote in his own notes for the piece:

“When the Spirit has attained the supreme culmination of its activity and has been torn away from the embraces of teleology and relativity, when it has exhausted completely its substance and its liberated active energy, the Time of Ecstasy shall arrive.”

Charles Ives: Like a Sick Eagle (c. 1906)

Charles Ives’s brief song “Like a Sick Eagle” contain just the first five lines of John Keats’s poem “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles”:

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

Clara Sipprell: Charles Ives (Washington, DC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Ives conveys the staggering weakness of the once-mighty bird through a spare accompaniment and ghostly vocal line.

The end result is deeply haunting and unsettling.

Darius Milhaud: Le Boeuf sur le toit (The Ox on the Roof) (1919-20)

During World War I, composer Darius Milhaud served in the French diplomatic service, spending two years in Brazil. Not surprisingly, the rich musical culture of South America rubbed off on Milhaud’s music.

Darius Milhaud

Milhaud himself once claimed that the title “Le Boeuf sur le toit” (which translates to “The Ox on the Roof”) was a reference to a Brazilian folk song.

However, there are potential alternate explanations, too:

- It’s the name of an imaginary cafe and dance hall (a real version opened a couple of years after Milhaud’s score was staged as a ballet).

- There is an old Parisian legend of a man who adopted a calf and brought it into his apartment, where it grew too large to be moved.

- Among musicians, the phrase “faire un boeuf” was slang for “to have a jam session.” When a cafe hosting a jam session was too small to host a group, musicians would be directed to the roof.

Regardless of exactly what the title refers to, the phrase is playful and evocative.

Paul Hindemith: Overture to the Flying Dutchman as Sight-read by a Bad Spa Orchestra at 7 in the Morning by the Well (c. 1925)

Composer and violinist/violist Paul Hindemith had a tongue-in-cheek sense of humour, as evidenced by this work, which is exactly what it sounds like: Hindemith’s idea of what an under-rehearsed ensemble might sound like while sight-reading Wagner’s Flying Dutchman Overture.

In it, he pokes fun at out-of-practice musicians trying to play a work beyond their technical abilities.

Paul Hindemith, 1923

You can hear their struggles: intonation issues, accidental entrances, wobbly cues.

At the end, the players inexplicably launch into a rendition of Émile Waldteufel’s The Skater’s Waltz.

La Monte Young: Composition 1960 #7: to be held for a long time (1960)

American composer La Monte Young was born in 1935. He is widely recognised as one of the first minimalists, and he has a special interest in sustained tones and musical drones.

The only instructions for the piece are that a B and an F-sharp are to be held “for a long time”. How long? It’s up to the performers – and perhaps the audience – to decide.

La Monte Young

Conclusion: The Weird and Witty World of Classical Music

Whether channeling apocalyptic mystical forces or memorialising a dead parrot, all of the composers above embraced a spirit of weirdness when it came to conceiving and naming their works.

These weird names pique our curiosity and invite us to listen with curiosity and fresh ears. Share with your music-loving friends, and let us know which one of these quirky works is your favorite.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)