It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Showing posts with label Klaus Doring. Classical Music. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Klaus Doring. Classical Music. Show all posts

Friday, January 2, 2026

Friday, December 5, 2025

Eight Pieces of Classical Music With the Weirdest Names

Most people think of classical music as being very serious. But in reality, classical music is often bizarre, sarcastic, or just plain weird.

Today, we’re looking at eight compositions with particularly weird titles, from Mozart’s cheeky “Leck mir den Arsch” to La Monte Young’s “Composition 1960 #7: to be held for a long time.”

We’re also looking at the fascinating stories behind them.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Leck mir den Arsch fein recht schön sauber (Lick my Arse for Six Voices) (ca. 1782)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart loved two things especially dearly: composing and scatological humour.

In fact, so much scatological humour appears in his letters that some scandalised editors of his correspondence actually scrubbed it from their editions!

Occasionally, his sense of humour boiled over from his letter-writing into his compositions, like in his three-part canon “Leck mich im Arsch”, which was likely meant to be a silly party song for his friends.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Translated to English, the expression “Leck mich im Arsch” means something equivalent to “kiss my ass.”

It’s a phrase that has no right to be arranged so cleverly or to sound so good…which of course is part of the joke!

Charles-Valentin Alkan: Funeral March on the Death of a Parrot (1859)

Composer Charles-Valentin Alkan is one of the most intriguing figures in classical music history.

He was a piano prodigy born in 1813 who, in the 1830s, was often mentioned in the same breath as Chopin and Liszt.

Charles-Valentin Alkan

However, after Alkan had a son out of wedlock in his mid-twenties, he withdrew from the concert stage for a time. He resumed his performing career in the mid-1840s. But after losing a prestigious job at the Paris Conservatoire and the devastating early death of Chopin, Alkan withdrew from public life again, focusing on studying and composing.

In 1859, Alkan wrote this parody funeral march, drawing from the pompous tradition of grand opera. It was composed for four voices, three oboes, and one bassoon.

The lyrics translated are “Have you eaten, Jaco? And what? Ah!” This is the French equivalent of the English expression “Polly wants a cracker?”

Alkan takes himself so seriously that if you just heard the music alone, you’d never guess the gentle, winking absurdity of the premise.

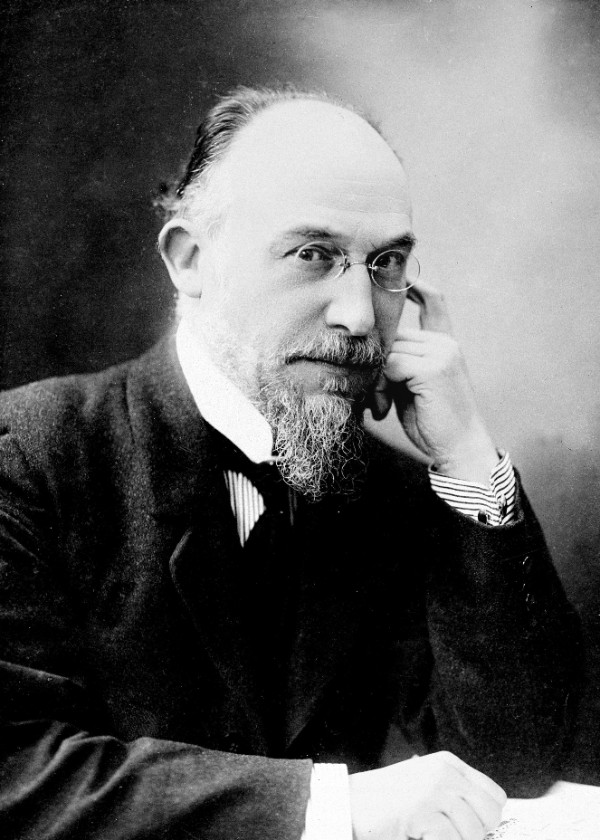

Erik Satie: Trois morceaux en forme de poire (Three Pieces in the Form of a Pear) (1903)

Composer Erik Satie specialised in absurdity, and his four-hand piano suite “Trois morceaux en forme de poire” offers absurdity in abundance.

The first joke is that, despite the title, the suite consists of seven pieces, not three.

According to legend, the “pear” part of the title originated with a criticism Claude Debussy leveled at Satie: namely, that Satie didn’t pay enough attention to form.

Erik Satie

Satie then chose a deliberately absurd shape so he could answer any criticism by Debussy by saying, “but it’s in the form of a pear!”

In France, pears also have a cultural connotation with the archetype of a fool or simpleton, meaning the joke may have been on Debussy, Satie himself, or maybe both!

Alexander Scriabin: The Poem of Ecstasy (1905-08)

Composer Alexander Scriabin believed that his life’s mission extended far beyond writing music.

In 1903, he began writing a work called Mysterium, which he continued working on for over a decade, until his death.

Alexander Scriabin

He wanted to stage a performance of it during a weeklong festival in the foothills of the Himalayas, after which he believed the end of the world would come, and human consciousness itself would shift.

In 1905’s The Poem of Ecstasy, we get a taste of his intense conviction and creative energy in a work that was actually finished. The narrative of the Poem follows a spirit achieving consciousness.

Scriabin wrote in his own notes for the piece:

“When the Spirit has attained the supreme culmination of its activity and has been torn away from the embraces of teleology and relativity, when it has exhausted completely its substance and its liberated active energy, the Time of Ecstasy shall arrive.”

Charles Ives: Like a Sick Eagle (c. 1906)

Charles Ives’s brief song “Like a Sick Eagle” contain just the first five lines of John Keats’s poem “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles”:

My spirit is too weak—mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagined pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

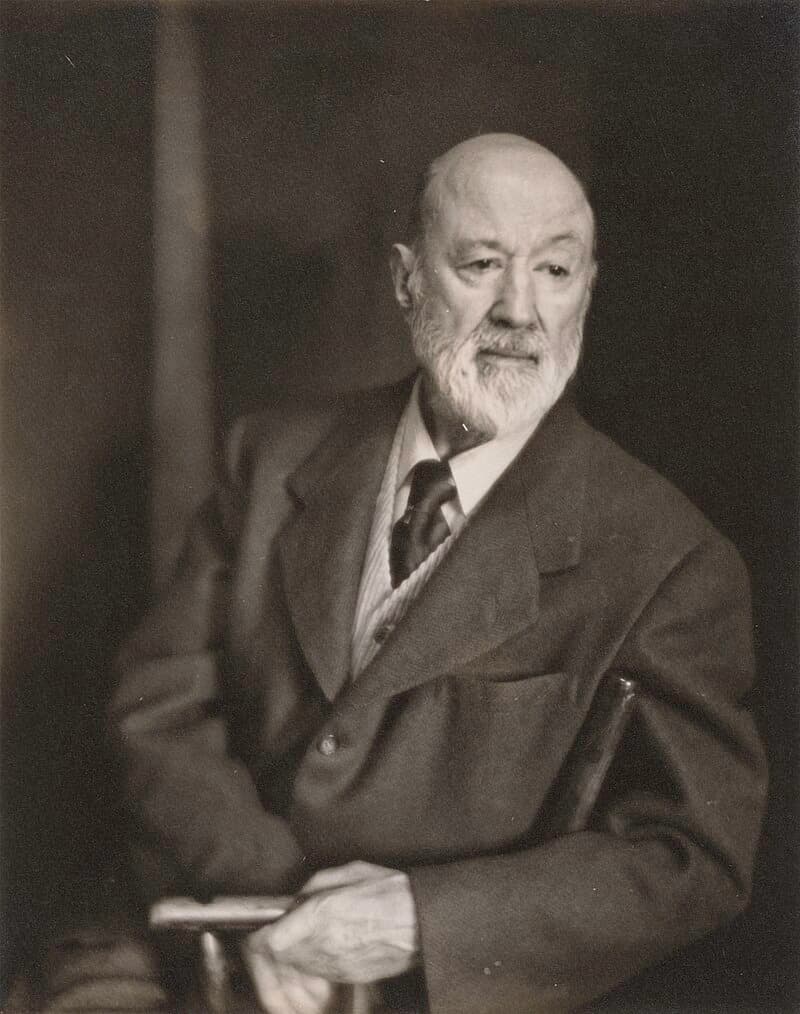

Clara Sipprell: Charles Ives (Washington, DC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Ives conveys the staggering weakness of the once-mighty bird through a spare accompaniment and ghostly vocal line.

The end result is deeply haunting and unsettling.

Darius Milhaud: Le Boeuf sur le toit (The Ox on the Roof) (1919-20)

During World War I, composer Darius Milhaud served in the French diplomatic service, spending two years in Brazil. Not surprisingly, the rich musical culture of South America rubbed off on Milhaud’s music.

Darius Milhaud

Milhaud himself once claimed that the title “Le Boeuf sur le toit” (which translates to “The Ox on the Roof”) was a reference to a Brazilian folk song.

However, there are potential alternate explanations, too:

- It’s the name of an imaginary cafe and dance hall (a real version opened a couple of years after Milhaud’s score was staged as a ballet).

- There is an old Parisian legend of a man who adopted a calf and brought it into his apartment, where it grew too large to be moved.

- Among musicians, the phrase “faire un boeuf” was slang for “to have a jam session.” When a cafe hosting a jam session was too small to host a group, musicians would be directed to the roof.

Regardless of exactly what the title refers to, the phrase is playful and evocative.

Paul Hindemith: Overture to the Flying Dutchman as Sight-read by a Bad Spa Orchestra at 7 in the Morning by the Well (c. 1925)

Composer and violinist/violist Paul Hindemith had a tongue-in-cheek sense of humour, as evidenced by this work, which is exactly what it sounds like: Hindemith’s idea of what an under-rehearsed ensemble might sound like while sight-reading Wagner’s Flying Dutchman Overture.

In it, he pokes fun at out-of-practice musicians trying to play a work beyond their technical abilities.

Paul Hindemith, 1923

You can hear their struggles: intonation issues, accidental entrances, wobbly cues.

At the end, the players inexplicably launch into a rendition of Émile Waldteufel’s The Skater’s Waltz.

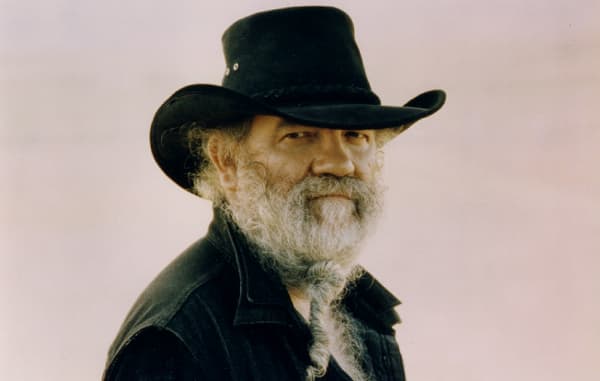

La Monte Young: Composition 1960 #7: to be held for a long time (1960)

American composer La Monte Young was born in 1935. He is widely recognised as one of the first minimalists, and he has a special interest in sustained tones and musical drones.

The only instructions for the piece are that a B and an F-sharp are to be held “for a long time”. How long? It’s up to the performers – and perhaps the audience – to decide.

La Monte Young

Conclusion: The Weird and Witty World of Classical Music

Whether channeling apocalyptic mystical forces or memorialising a dead parrot, all of the composers above embraced a spirit of weirdness when it came to conceiving and naming their works.

These weird names pique our curiosity and invite us to listen with curiosity and fresh ears. Share with your music-loving friends, and let us know which one of these quirky works is your favorite.

Thursday, July 17, 2025

Tomaso Albinoni - Adagio (best live version) Copernicus Chamber Orchestra

Saturday, June 28, 2025

Johann Strauss II - The Blue Danube

Embark on a breathtaking, impressionistic journey along the legendary Danube and into the heart of Vienna, set to the enchanting rhythms of the Blue Danube Waltz. This visually stunning film unfolds in seven poetic chapters, where dawn’s first light awakens lush river landscapes and a graceful couple begins their timeless dance on the misty banks. As their waltz flows in harmony with the river, nature and movement become one—petals drift, sunlight shimmers, and the boundaries between dancers, water, and wildflowers dissolve in a swirl of color and light.

Composed by Johann Strauss II in 1866, "The Blue Danube" ("An der schönen blauen Donau") is one of the most beloved and recognizable waltzes in the world. Often called the "Waltz King," Strauss captured the elegance and spirit of Vienna in his music, and this masterpiece has become an enduring symbol of the city and its cultural heritage. With its sweeping melodies and enchanting rhythms, the Blue Danube Waltz continues to inspire audiences and evoke the timeless beauty of the river that flows through the heart of Europe.

The story sweeps from tranquil mornings to the dazzling splendor of Viennese ballrooms, alive with swirling gowns, sparkling chandeliers, and golden music notes that seem to float through the air. As night falls, Vienna’s lights reflect on the Danube’s surface, and the city transforms into a living painting—impressionistic, magical, and full of wonder. In the final moments, the scene dissolves into pure color and music, leaving only the luminous outline of the river, eternal and ever-flowing.

Blending music, art, and animation, this film is a celebration of beauty, romance, and the timeless spirit of the Danube and Vienna—an unforgettable visual poem that will linger in your memory long after the last note fades.

Composer: Johann Strauss II

Conductor: Ondrej Lenard

Orchestra: Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra

Thursday, June 26, 2025

Beegie Adair, David Davidson - C'est Magnifique (Visualizer)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

S. Rachmaninoff, Rhapsody on a theme by Paganini op.43,

Monday, January 13, 2014

Ten Unsolved Music's Great Mysteries

1. The

great Baroque violinist Jean-Marie Leclair was brutally stabbed to

death in a dangerous Parisian neighbourhood in 1764. But whodunnit? Was

it his ex-wife, intent on financial gain? Or Leclair’s nephew,

appropriately named Vial. Or could it have been the work of another

musician envious of Leclair's brilliance? We may never find out.

2. Who was Beethoven’s ‘immortal beloved’?

Beethoven

was a bit of a failure when it came to romance, falling impractically

in love with elegant, society women, including one he addressed as

‘immortal beloved’ in a famous love letter of July 1812. The recipient

of the letter has been the subject of much speculation. The two

candidates most favoured today are Antonie Brentano (pictured) - an

Austrian patroness of the arts - and Countess Jozefina Brunszvik de

Korompa, who received at least 15 love letters from Beethoven in which

he swore his eternal devotion to her.

3. How did Tchaikovsky die?

Tchaikovsky died at

the age of 53 on 6 November 1893. The official cause was reported to be

cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water

several days earlier. However, his death is still a mystery. If he did

contract cholera, it is impossible to know precisely when or how he

became infected. Or did he commit suicide after facing a 'court of

honour' investigating his sexual behaviour? Was the Tsar of Russia

himself behind the great composer's death? Or did Tchaikovsky end it all

after falling for his nephew, Bob? All possible, all very tragic.

4. The case of the missing Sibelius symphony

Sibelius

worked on his Symphony No.8 from the mid-1920s until around 1938, but

never had it published. He repeatedly refused to release it for

performance, while continuing to assert that he was working on it even

after it was claimed it had been burned in 1945. It was only in the

1990s that experts raised the possibility that some of the music may

have survived in notebooks. Three short manuscript sketches – comprising

less than three minutes of music – have been recorded by the Helsinki

Philharmonic Orchestra, but will the full work ever be discovered and

performed?

5. Who killed Stradella?

The Italian Baroque

composer Alessandro Stradella was stabbed to death in 1682 but his

killer was never caught. Admittedly the composer was not without

enemies: he had attempted – and failed – to embezzle money from the

Church and had enough high-profile affairs with women to make him pretty

unpopular among the great and the good of Rome and Venice.

6. Where are the remains of Thomas Tallis?

The

great English composer Thomas Tallis died at his home in Greenwich in

1585. He was buried in St. Alfege’s Church in Greenwich. To this day,

the exact location in the church of Tallis's remains is unknown. It’s

feared they may have even been discarded by labourers between 1712 and

1714, when the church was rebuilt.

7. What was Elgar’s ‘enigma’?

For

his Variations on an Original Theme for Orchestra, Elgar wrote a set of

14 variations on a hidden theme that is, in the composer's own words,

'not played'. Various musicians have proposed theories about what the

missing melody could be, although Elgar never actually claimed his theme

was a melody. It could be something else - such as a symbol or a

literary allusion. Elgar rejected all of the solutions proposed in his

lifetime, and took the secret with him to the grave.

8. The tomb of the two-headed composer

Eight

days after the funeral of Joseph Haydn in May 1809, two phrenologists

stole his head hoping to see if the composer's genius was somehow

reflected in the bumps and ridges of his skull. Eleven years later,

Haydn's patron Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II wanted to have Haydn's

remains transferred and was furious to find they had no skull. The

phrenologists gave him a different skull to bury with the rest of the

body. In 1895, the real skull turned up again when it was willed to a

music society in Vienna. In 1954, it was finally reunited with the rest

of Haydn’s body – but the substitute skull was never removed. There are

now two skulls in Haydn’s tomb - but which is his?

9. The mystery of the women who channeled composers

In

the 1970s, Londoner Rosemary Brown caused a sensation when she claimed

that dead composers were dictating new musical works to her. Debussy,

Grieg, Liszt, Chopin, Stravinsky, Bach, Brahms, Beethoven, Schumann and

Rachmaninov were all queuing up to get their compositions through to

her, she said. Reportedly a mediocre pianist herself, Brown even

channelled a 40-page sonata from Schubert, as well as Beethoven's 10th

and 11th Symphonies. Experts said the pieces were just sub-standard

re-workings of some of those composer's better-known compositions. Well

they would, wouldn't they?

10. Was Beethoven killed by his doctor?

There is

much disagreement over how Beethoven died. An autopsy revealed

significant liver damage, which may have been caused by heavy alcohol

consumption. Then there is the speculation - of syphilis, infectious

hepatitis, sarcoidosis and even the gastro-disorder called Whipple's

disease. More recently, examination of hair clippings from Beethoven

(pictured) have led to the assertion that he was poisoned to death by

excessive doses of lead-based treatments administered under instruction

from his doctor.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)