It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, June 17, 2023

How Inspiration Strikes

By Georg Predota, Interlude

Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven on a Walk by Berthold Genzmer

As the American painter, artist and photographer Chuck Close famously stated, “Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration, the rest of us just show up and go to work.” Beethoven, for example, went for vigorous walks through the forests and hills surrounding Vienna after lunch. He always carried with him a pencil and a small pocket sketchbook, recording any musical ideas that would thus come to his mind.

Gustav Mahler

Mahler’s Komponierhäuschen

Gustav Mahler not only locked himself in various Komponierhäuschen (Composer’s cottages), he also took 3 to 4-hour walks after lunch, recording his musical impressions in a notebook.

Benjamin Britten

For Benjamin Britten, afternoon walks were “where I plan out what I’m going to write in the next period at my desk”.

Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss preferred to compose in his garden cottage until lunchtime, when it was time to head for the local restaurant.

Christoph Willibald Gluck

Solitary walking, however, was clearly not the only source of inspiration for great musical minds. Gluck, it was said, wrote best when he was sitting in the middle of a field.

Gioachino Rossini

Rossini was most productive when he had partaken of “a good flask of wine.”

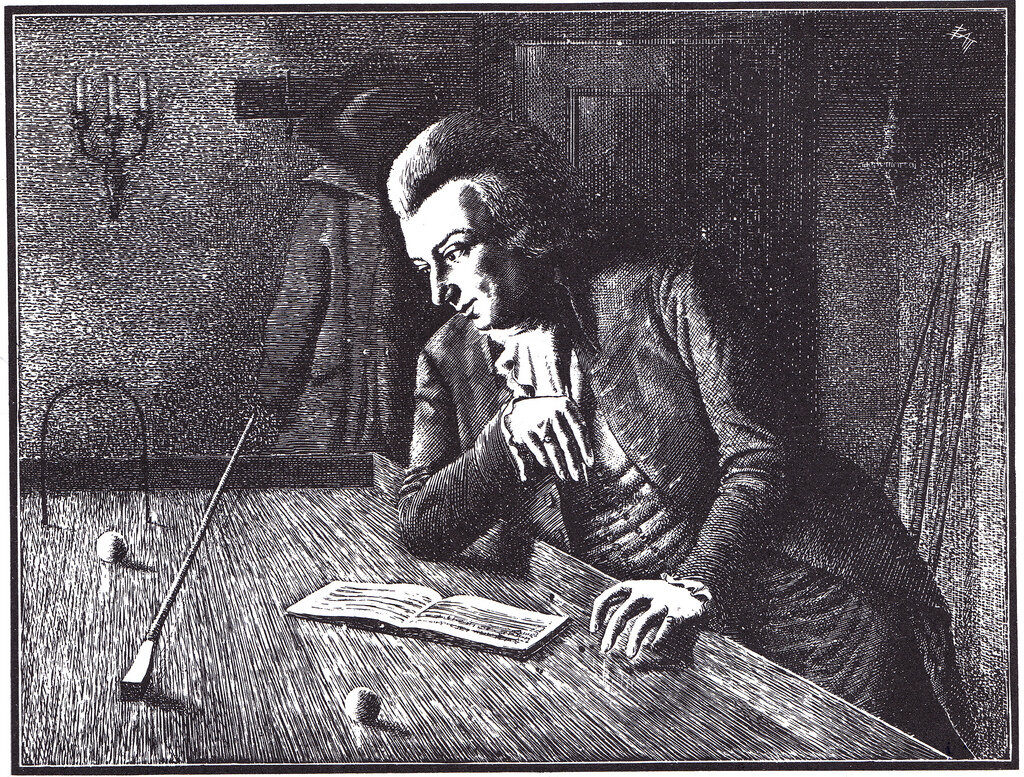

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart at the Pooltable by Oswald Charles Barret

It is said that Mozart composed his best music while playing billiards

Giovanni Paisiello

Paisiello enjoyed composing while lying in bed.

Antonio Sacchini

A pretty woman by his side, and his pet cats playing around his feet was a prerequisite for Sacchini to write well.

Giuseppe Sarti

© inhabitat.com

Sarti preferred to sit in a dark gloom lighted only by a single candle.

Domenico Cimarosa

Cimarosa composed his best works surrounded by a dozen of gabbling friends, with light conversation inspiring his music.

Étienne Méhul

Mćhul, on the other hand, trying to get away from the noise and bustle of the city. Once, he went to the Chief of Police in Paris and asked to be imprisoned in the Bastille.

Richard Wagner

And let’s not forget Richard Wagner, who liked his silken undies and heavy perfume in order to be properly inspired. He also needed perfect quiet, and nobody was allowed entrance to his study—it is reported that even his meals were passed to him through a trap door. Believe it or not!

Gershwin’s Forgotten Rhapsody

Gershwin’s Forgotten Rhapsody

We all know George Gershwin (1898–1937) and his Rhapsody in Blue, his 1924 composition that, beginning with an extended clarinet glissando, firmly issued jazz into the world of classical music. The work was commissioned by bandleader Paul Whiteman and received its premiere at Aeolian Hall in New York with George Gershwin at the piano. Gershwin wrote it, Whiteman’s arranger Ferde Grofé orchestrated it, and history was made.

Carl Van Vechten: George Gershwin, 1937

It was written in the 5 weeks between the announcement of the commission (small detail: Gershwin had already declined to do it!) and the concert on February 12, 1924. Gershwin fleshed most of it out on a train trip between New York on Boston, where the ‘rattle-ty bang’ of the train inspired him and by the end of the journey, he had the structure in place. He started formal composition on 7 January and passed the score to Grofé on 4 February, a mere 8 days before the concert.

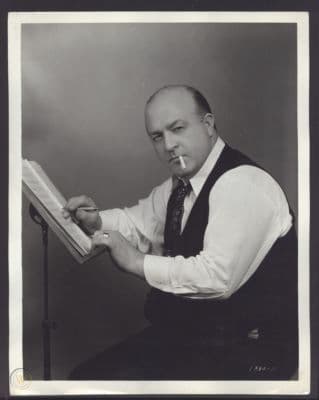

Paul Whiteman

Ferde Grofé, 1935

Billed as “’An Experiment in Modern Music”, Whiteman’s classical/jazz concert had 26 different pieces on the programme. Gershwin’s piece was no. 25. The earlier works hadn’t always been successfully received and the ventilation system in the hall wasn’t working. Gershwin took his place at the piano and with that unmistakable wail on the clarinet, the fleeing audience was stopped in its tracks and a new era in classical music was born.

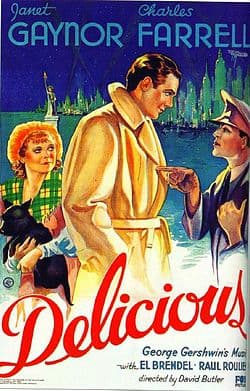

What’s been largely overlooked, however, is that Gershwin wrote another jazz concerto, the Second Rhapsody. In 1931, Gershwin was in Hollywood, writing music for the movies, when he was asked for a six-minute instrumental interlude for the movie Delicious, an early colour film set in Manhattan involving a newly arrived Scottish girl who falls in with a miscellaneous group of immigrant musicians.

“Delicious” film poster

Gershwin wrote more music than Fox Studios needed and nearly half of his music ended up on the editing room floor, but Gershwin took it to the recording studio on its own. It was given its concert premiere in January 1932 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky, with Gershwin as soloist.

The most common version heard for the first 50 years after its composition was a re-orchestration done by Robert McBride, as commissioned by the music editor at Gershwin’s publisher. In this edition, Gershwin’s original vision has been simplified, voices reassigned (for example, the string quartet portion of the adagio was rescored for violin, clarinet, oboe, and cello), and former solo lines were now doubled. Also, 8 measures cut by Gershwin were added back in by McBride. The soloist is Gershwin’s friend, Oscar Levant (1906–1972).

Oscar Levant in An American in Paris, 1951

Various versions ended up in circulation – some cut down by Gershwin, some cut down by other editors – and it’s only since 1985, when conductor Michael Tilson Thomas started researching the original version that Gershwin wrote, that we start to approach the original. MTT recorded what he found with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in 1985.

The motifs are pure New York in the 1930s: the hammering motif at the beginning depicts riveters at work on the city’s skyscrapers, remember that the world’s tallest building, the Empire State Building, was begun in 1930 and completed in 1931, dominating the New York skyline until the World Trade Center towers eclipsed it in 1970.

Empire State Building, 2012

Riveters at work

This is what gave the work one of its earliest names: Rhapsody in Rivets. It was next given the title of New York Rhapsody, then Manhattan Rhapsody before Second Rhapsody came to the fore. In addition to the rivets, other elements of the city come in as well, with Latin rhythms providing a driving force along with the rivets. Jazz and blues also have their place. This performance by Freddy Kempf says it’s ‘in the original 1931 orchestration by the composer’.

Some blame the excessive percussive rhythms for the work’s lack of popularity, others for the lack of a definitive score that preserves Gershwin’s original ideas. The Gershwin family, as part of a larger project to create scholarly editions of Gershwin’s music in conjunction with the Library of Congress and the University of Michigan, is working on a definitive edition of the work that should help it get back onto the concert stage.