Three of Rossini’s operas mark turning points in his development as an opera composer. Semiramide, Guillaume Tell, and La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie) each gather up a summary of his operatic development to that point and are made into very long operas. They also share another characteristic: none of these operas show the self-borrowing that marks much of his work. Semiramide is the culmination of his opera seria work and is the turning point in his withdrawal from Italian operatic life. Guillaume Tell is the end of the series of his operas written in Naples and then Paris, which were about experimentation and exploration – this is his farewell to his career in the theatre. La gazza ladra, with its mix of serious and comic elements, is his last experiment in comic opera. His next area was the musical farce (farse), starting with L’Italiana in Algeri, where his operas called for the top soloists to take on his difficult principal roles.

Marie Françoise Constance Mayer: Gioachino Rossini (Pesaro: Casa Rossini)

La gazza ladra, which sits between opera seria and comic opera, is an opera semiseria. The opera received its premiere on 31 May 1817 at La Scala, Milan.

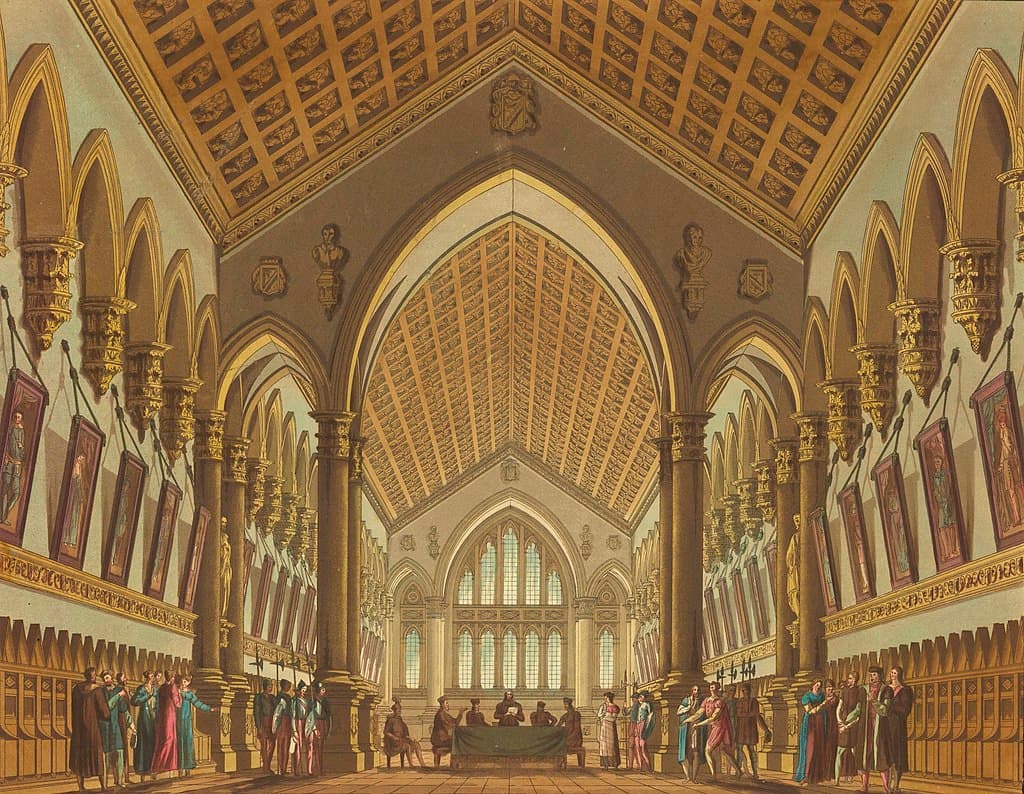

Many opera semiseria, also called melodrama, were ‘rescue operas’ which involved a class conflict between the feudal aristocracy and regular society, generally peasants. The settings are usually the village square, with the nobleman’s house (or the local prison) looming over the scene. In La gazza ladra, the climax is set in the nobleman’s court, pushing the emphasis over to a more opera seria ending.

José Álvarez Cubero: Bust of Gioachino Rossini, ca. 1819 (private owner)

Ninetta loves Giannetto, who is on his way back from the wars. Her father, Fernando, a deserter from the army, shows up and asks her to sell two of their silver spoons so he has some money. She gathers up the spoons and is interrupted by the mayor who asks her to read out the description of a deserter in the area. She makes up a different description of her father, and while she’s doing that, a magpie swoops down and steals a spoon.

Alessandro Sanquirico: Tribunal del podestà in un grosso villaggio non molto distante da parigi : questa scena su eseguita pel melodramma La Gazza Ladra, posto in musica dal sig. Gioachimo Rossini, e rappresentato nell’J. R. Teatro alla Scala (Design for courtroom scene (Act II: 9)) (Gallica: btv1b53117267k)

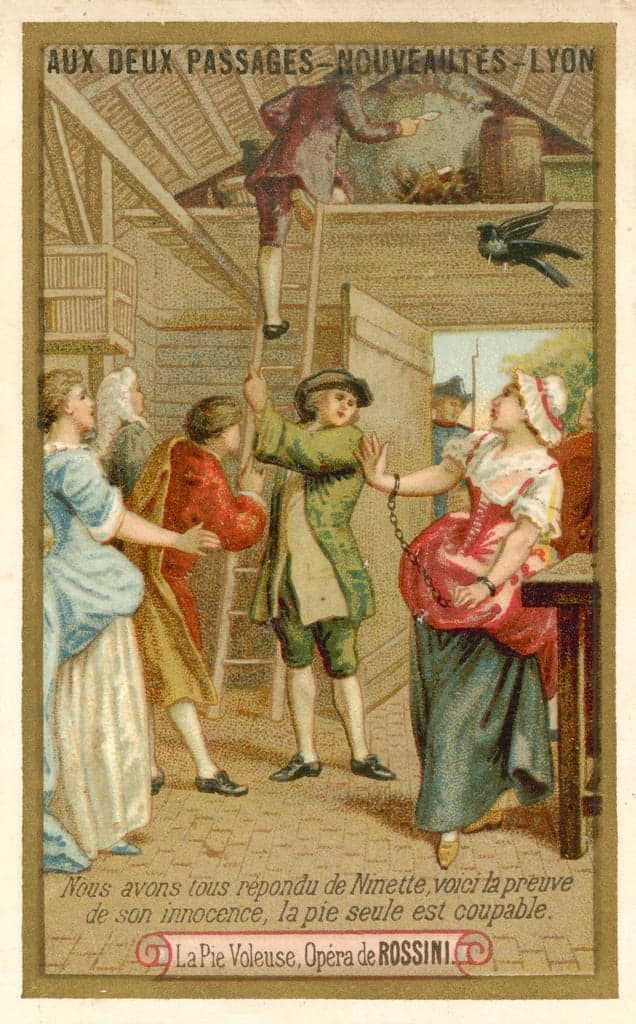

Giannetto’s mother, who is not in favour of Ninetta, accuses Ninetta of theft, and as the two family spoons have the same initials on them, Ninetta is found guilty and sent to the scaffold. The magpie steals a silver coin, and when it’s followed to its nest, both Ninetta’s and Gianetta’s mother’s lost spoons are found. Will the discoverers get back to the scaffold in time to save Ninetta? Of course they do, and all have a happy ending, except the Mayor, who was hoping Giannetta’s troubles would be solved in his arms.

Discovery of the magpie’s nest

The overture, which starts with a snappy drum roll, is significant for its use of snare drums.

Gioachino Rossini: La gazza ladra Overture

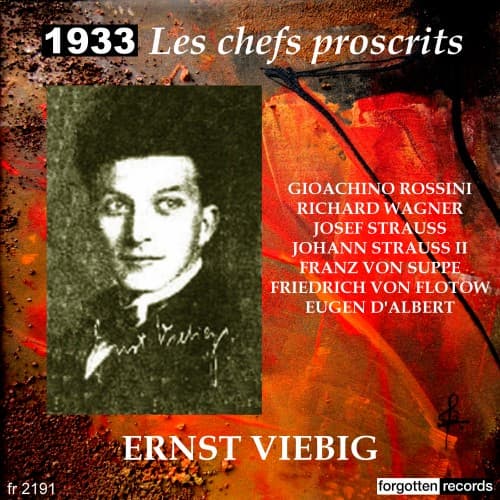

This 1928 recording was conducted by Ernst Viebig, leading the Berlin State Opera Orchestra. Ernst Viebig (1897–1959) was an accomplished composer from a family with literary connections. His father was a publisher and his mother a writer. His original name was a hyphenated version of his parents’ names, Cohn-Viebig, and was shortened to Viebig in 1914 when he wanted to join the army. The family hoped that eliminating his father’s Jewish name would make his way easier. His father had converted to Lutheran Protestantism when he married Clara Viebig.

Ernst Viebig

Family connections brought the world of literature to the house and his own interests in music started with the piano, with a particular skill in improvisation. He served in WWI and returned to Berlin with a position at the Electrola record company as musical director, while also serving as a bandmaster and composer. With the rise of the National Socialists in Germany and an inquiry by the Gestapo about his Jewish background, he decided to leave Germany for South America. His music did not find favour there and he and his second wife opened a German bookstore in Rio de Janeiro and then in São Paulo. He returned to Berlin in 1958 but could not find work and retired to Lower Bavaria where he died in 1959.

As the musical director at Electrola in the 1920s, he played an important role in their recordings. As a conductor, he made not only this La gazza ladra recording but also important recordings of the overture to von Suppé’s operetta The Beautiful Galathée and Puccini’s Turandot Fantasy.

Performed by

Ernst Viebig

Berlin State Opera Orchestra

Recorded in 1928

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter