– and does it really exist?

It’s a superstition that plagued some of the great composers of the 19th and 20th centuries – but is there any truth in it?

The ‘Curse of the Ninth’ is a superstition that developed during the late period – some people believed that composers were fated to die during or after writing their ninth symphony.

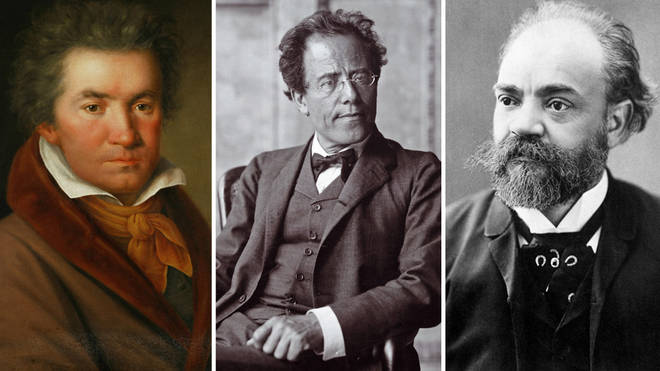

On the surface, the theory seems like it might have some basis in fact: , , and all died after completing their Ninths, Anton Bruckner died with his Ninth unfinished – and contracted pneumonia while writing his tenth.

But like all good conspiracy theories, the Curse of the Ninth has been debunked and dismissed. Here’s the real story.

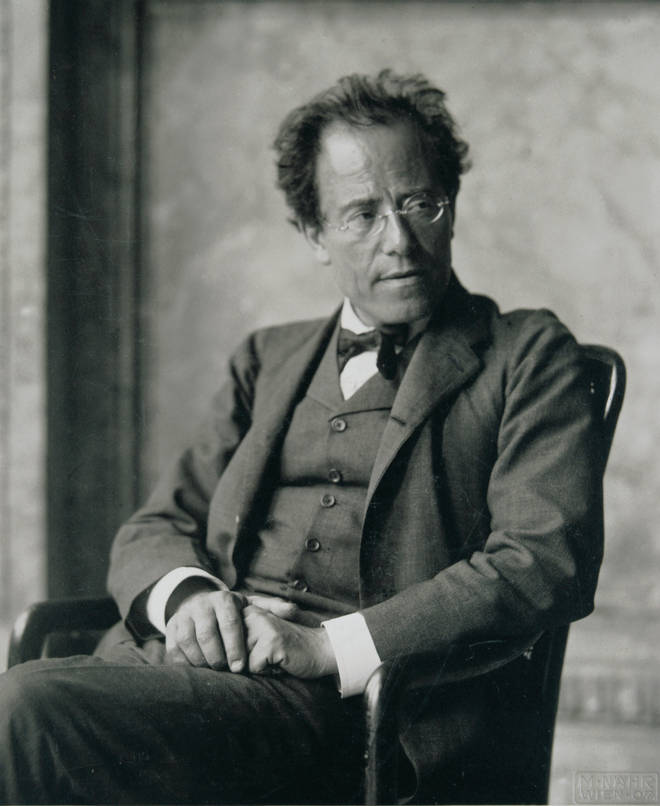

It all started with Mahler… kind of

Gustav Mahler, who wrote some of the most glorious symphonies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was one of the first composers to believe in a superstition surrounding ninth symphonies.

But Mahler was a little *too* obsessed with the idea. Seeing how fate had struck down Beethoven and Bruckner before him, he came up with a cunning plan to beat the curse.

After completing his eighth symphony, Mahler wrote a piece of music (Das Lied von der Erde) that was, in essence, a symphony – but he refused to call it one.

He then finished his ninth symphony and set to work on his tenth – but then he contracted pneumonia while writing it and died in 1911, aged 51, apparently proving the superstition correct.

But Mahler didn’t know about Schubert, Dvořák... or any of the others

Arnold Schoenberg, whose music was heavily influenced by Mahler, described the Curse of the Ninth in an essay on the composer: “He who wants to go beyond it must pass away. It seems as if something might be imparted to us in the Tenth which we ought not yet to know, for which we are not ready. Those who have written a Ninth stood too close to the hereafter.”

There are a few issues with this theory. Because of the time he was writing, the only victims of the ‘curse’ that Mahler would have been aware of were Beethoven and Bruckner.

He wouldn’t have known about Schubert’s nine symphonies – because what is now called his Symphony No. 9 (the ‘Great’) was known as his Seventh in Mahler’s time.

Plus, Dvořák’s Ninth ‘New World’ Symphony wasn’t even considered a ‘ninth’ in Mahler’s time. It was published as his Symphony No. 5, before four extra symphonies appeared after Dvořák’s death. And Spohr – who is often included on the ‘curse’ list – wrote and completed a tenth symphony, but withdrew it.

Even Bruckner doesn’t fully qualify; he died before completing his (unfinished) Ninth Symphony – which brings his total symphonies to just eight.

But lots of composers have written more than nine symphonies...

Yes. The main snag with the Curse of the Ninth is that it only really makes sense if you concentrate on a relatively small number of 19th and 20th-century composers, omitting composers like , who wrote 15 symphonies, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, who wrote 12.

There’s also the most famous Classical composers: Mozart, for instance, wrote 41 symphonies, while wrote a whopping – 106 if you count the unnumbered ones (there was no stopping that man).

And then there’s Leif Segerstam’s casual 327 symphonies…

The Curse of the Nine is a great story, and it probably fuelled a lot of the angst behind Mahler’s heart-wrenching symphonies. But perhaps it’s best to treat it as a superstition.