As a quick recap, you get a piano quartet when you add a piano to a string trio. The standard instrument lineup for this type of chamber music pairs the violin, viola, and cello with the piano. In its development, the piano quartet had to wait for technical advances of the piano, as it had to match the strings in power and expression.

© serenademagazine.com

Piano quartets are always special because the scoring allows for a wealth of tone colour, occasionally even a symphonic richness. The combined resources of all four instruments are not easy to handle, and the number of works in the genre is not especially large. However, a good many of the extant piano quartets are very personal and passionate statements.

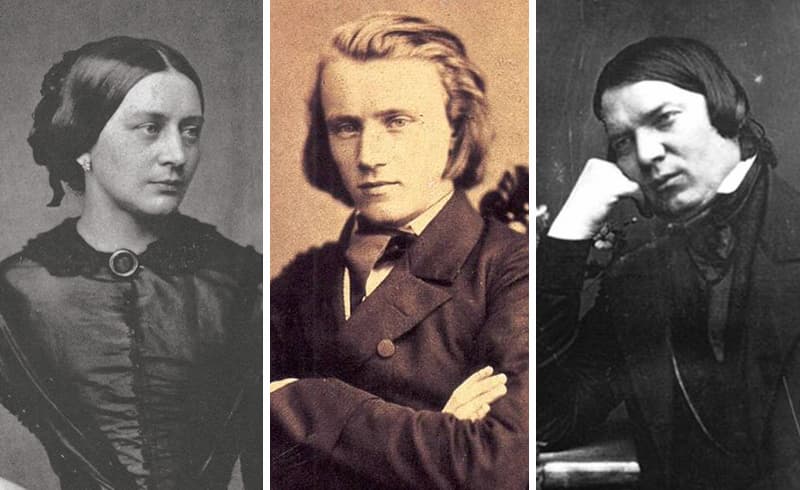

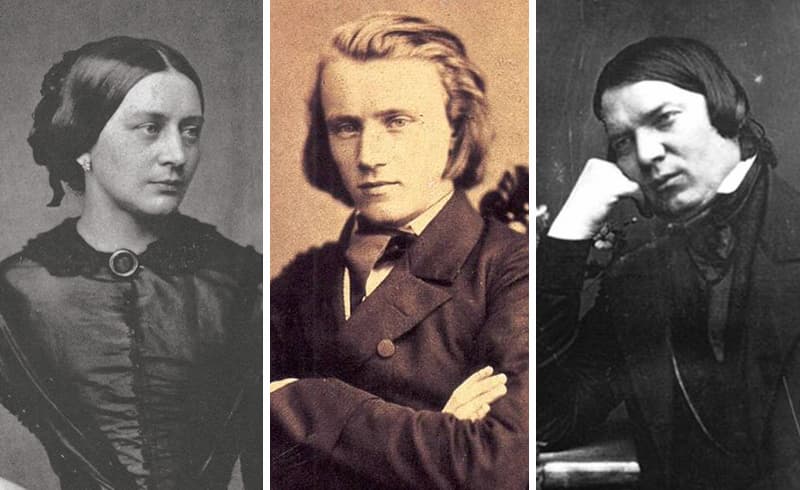

When talking about chamber music, and specifically chamber music with piano, it is difficult to avoid Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Lucky for us, Brahms wrote three piano quartets, and his Op. 60 took its inspiration from his intense relationship with Clara Schumann. However, it took Brahms almost twenty years to complete the work. The origins date back to around 1855 when Brahms was wrestling with his first piano concerto.

Brahms put this particular piano quartet aside and only showed it to his first biographer in the 1860s with the words, “Imagine a man who is just going to shoot himself, for there is nothing else to do.” Thirteen years later, Brahms took up the work and radically revised it. He probably wrote a new “Andante” and also a new “Finale.” In the end, the work finally premiered on 18 November 1875 with Brahms at the piano and the famous David Popper on cello.

Brahms and the Schumanns

The emotional distress of his relationship with Clara is presented in a mood of darkness and melancholy. A solitary chord in the piano initiates the opening movement, with the string presenting a theme built from a striking two-note phrase. Some commentators have suggested that Brahms is musically speaking the name “Clara” in this two-note phrase. The second theme is highly lyrical but quickly develops towards the dark mood of the opening. The “Scherzo” is also in the minor key, and the deeply felt slow movement is a declaration of love for Clara. The dark opening returns in the final movement, and while the development presents some relief, the work still ends on a note of resignation, albeit in the major key.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

The intensely emotional and meticulously crafted compositions by Brahms served as models for a number of composers, among them Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900). As he writes, “Brahms helped me, by the mere fact of his existence, to my development, my inward looking up to him, and with his artistic and human energy.” While Brahms respected Herzogenberg’s technical craftsmanship and musical knowledge, he never really had anything to say.

Herzogenberg was undeterred and never stopped composing. In 1897, he wrote to Brahms, “There are two things that I cannot get used not to doing: That I always compose, and that when I am composing I ask myself, the same as thirty-four years ago, ‘What will He say about it?’ To be sure, for many years, you have not said anything about it, which is something that I can interpret as I wish.”

A few days before Brahms’ death, Herzogenberg presented him with his probably best and most mature work, the Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95. The gripping “Allegro” is full of unmistakably Brahmsian character, constructed with compositional economy. An introductory chord develops into the motific core of the entire movement. The “Adagio is full of dreamy intimacy, while the capricious “Scherzo” eventually transports us into a pastoral idyll. Three themes, including a folkloric principle theme, combine in a spirited and temperamental “Finale.”

When Richard Strauss (1864-1949) left college and moved to Berlin to study music at the age of 19, he suddenly discovered a new model in Johannes Brahms. Strauss would meet his current idol personally at the premiere of Brahms’ 4th Symphony in 1885. Under the influence of Brahms, the teenaged Strauss completed his Piano Quartet in C minor in 1884, and a good many commentators believe it to be Strauss’ “greatest chamber work.”

Richard Strauss

Op. 13 is a large work fusing “the sobriety and grandeur of Brahms with the fire and impetuous virtuosity of the young Strauss.” The work opens quietly, and the deceptively simple motif returns in various disguises. However, the music quickly explodes with superheated energy, and its dark sonorities and dramatic scope drive it to a virtually symphonic close.

Finally, the “Andante” introduces a measure of calm, with the piano sounding a florid melodic strain that gives way to a lyrical second subject in the viola. Both themes are gracefully extended while bathing in a delicate and charmed atmosphere. The concluding “Vivace” returns to the mood of the opening movement, and the rondo design also features a serious refrain and a spiky fugato. The work won a prize from the Berlin Tonkünstler, Strauss, however, would say goodbye to chamber music and explore orchestral virtuosity in his great tone poems.

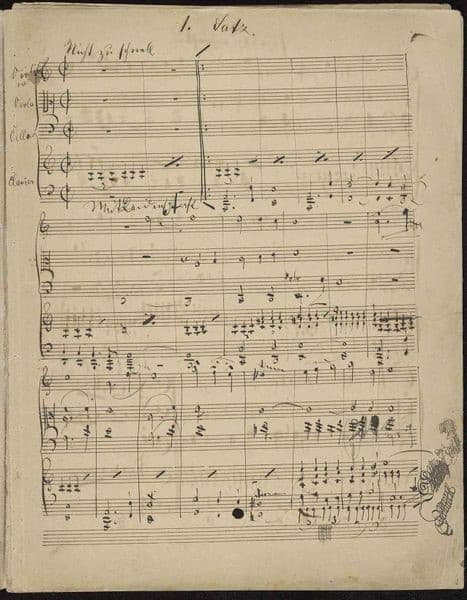

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) seems another surprising entry into a blog on the piano quartet. However, a single movement from his student days at the Vienna Conservatory does survive. Mahler took piano lessons from Julius Epstein and studied composition and harmony under Robert Fuchs and Franz Krenn. Mahler left the Conservatory in 1878 with a diploma but without the coveted and prestigious silver medal given for outstanding achievement.

Gustav Mahler’s Piano Quartet

Although he claimed to have written hundreds of songs, several theatrical works, and various chamber music compositions, only a single movement for a Piano Quartet in A minor survived the ravages of time. Composed in 1876 and awarded the Conservatory Prize, it is strongly influenced by the musical styles of Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms.

Conveying a sense of passion and longing, Mahler presents three contrasting themes within a strict formal design. The opening theme possesses an ominous and foreboding character, while the contrasting second—still in the tonic key—is passionately rhapsodic. To compensate for this tonal stagnation, the third theme undergoes a series of modulations. Thickly textured and relying on excessive motivic manipulation, this movement nevertheless provides insight into the creative processes of the 16-year-old Mahler.

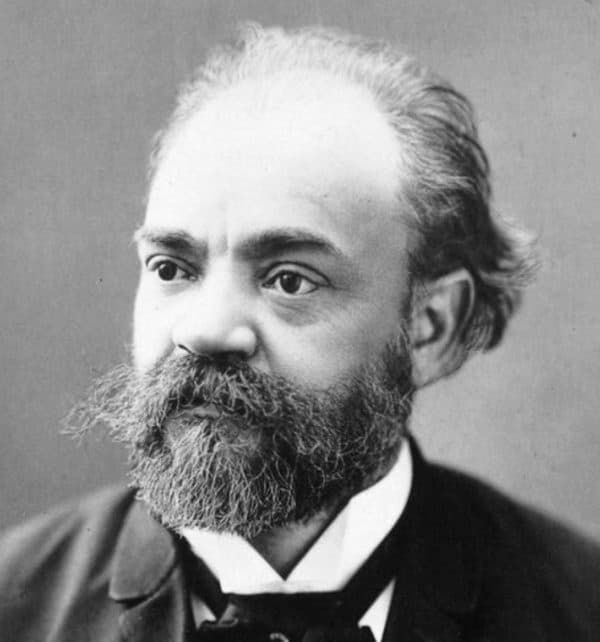

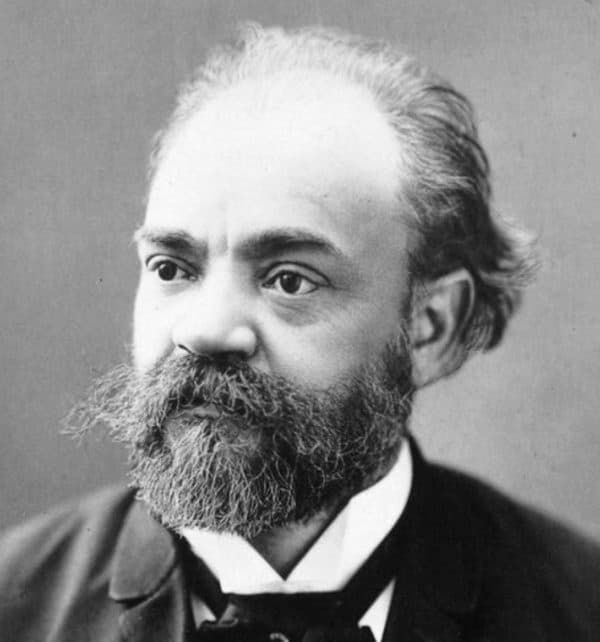

Antonín Dvorák (1841-1904) is another composer who, for a time, took his bearings from Johannes Brahms’s music. Dvorák had always been strongly drawn to chamber music, as his first published works are a string quartet Op. 1 and a string quintet Op. 2.

Dvořák in New York, 1893

Apparently, he composed his D-Major piano quartet in a mere eighteen days in 1875. It premiered five years later, on 16 December 1880. Surprisingly, this piano quartet has only three movements, as the composer combines a scherzo and Allegro agitato in alternation in the Finale. The opening “Allegro” sounds like a rather characteristic Czech melody, initiated by the cello and continued by the violin. By the time the piano takes up the theme, the tonality has shifted to B Major.

The melody of the slow movement, a theme followed by five variations, is introduced by the violin. Dvorák skillfully presents fragments of the theme in various meters and textures. The cello, accompanied by the piano, takes the lead in the final “Allegretto.” After the violin has taken up the theme, the piano takes us into the finale proper.

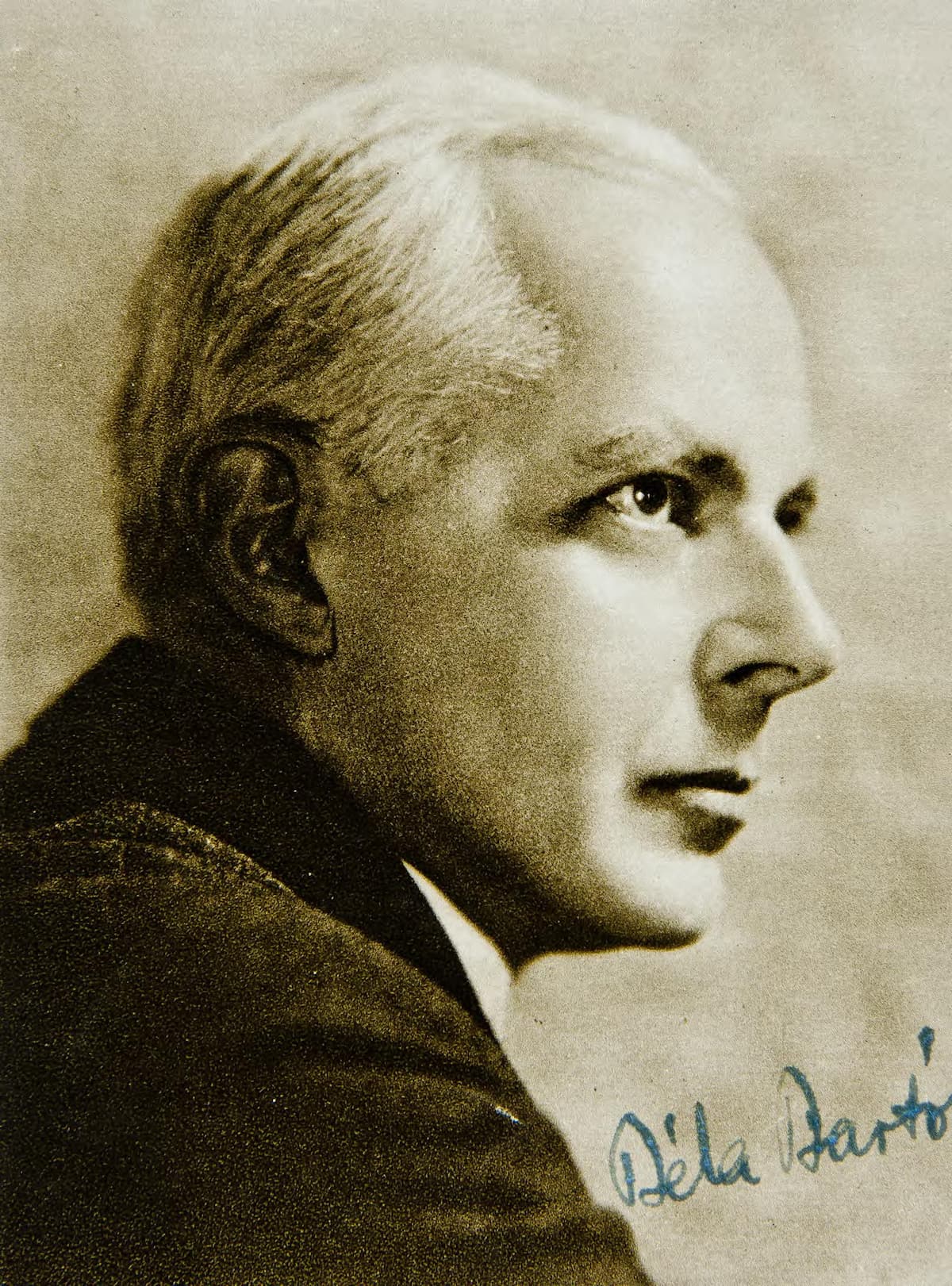

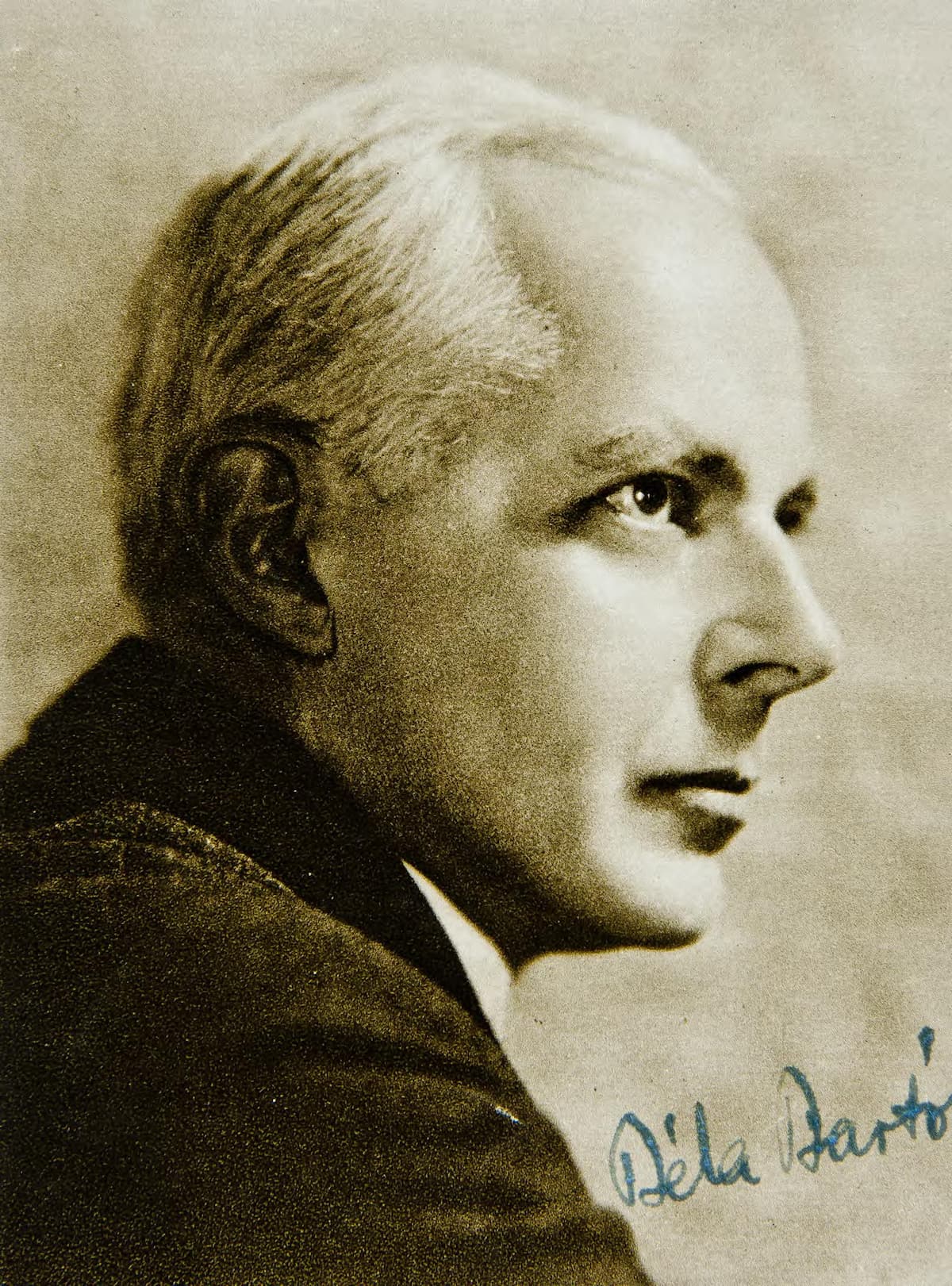

Béla Bartók: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 20

Béla Bartók

To his contemporaries and critics, Johannes Brahms looked like a bastion of musical conservatism. Surprisingly, it was Arnold Schoenberg, in his celebrated Radio address entitled “Brahms the Progressive”, who suggested that Brahms was “a great innovator in the realm of musical language and that his chamber music prepared the way for the radical changes in musical conception at the turn of the 20th century.”

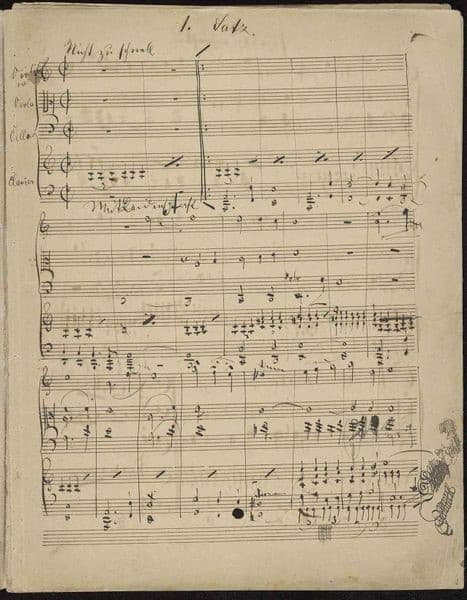

Just one year after Brahms’ death, the teenage Béla Bartók (1881-1945) embarked on the composition of a four-movement piano quartet. For years, this score was believed to have been lost, but it was rediscovered by a member of the “Notos Quartet,” who also prepared the edition following the composer’s autograph score. What is more, they also presented a world premiere recording in 2007.

The opening “Allegro” immediately evokes the harmonic and sensuous soundscape of Johannes Brahms. And like his model, Bartók’s musical prose does not follow a predictable pattern as the boundaries and distinctions of theme and development are blurred. Brahms’ rhythmic shapes are the topic of a blazing “Scherzo,” with the “Trio” sounding a sombre lyrical contrast. The “Adagio” sounds like a declaration of love for Brahms, while the “Finale” brims with spicy Hungarian flavours.

Camille Saint-Säens introduced Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) to Pauline Viardot in 1872. Her youngest daughter, Marianne, immediately stole his heart, and Fauré courted her for four painful years. In July 1877, she finally agreed, and the engagement was announced. However, the relationship only lasted until the late autumn of 1877, when Marianne suddenly broke off the engagement.

Pauline Viardot

The exact reasons remain unclear, and Fauré was deeply distressed, with friends reporting that his “sunny disposition took a dark turn.” He started to suffer from bouts of depression, and the Clerc family helped him to recover. At this point, Fauré composed the masterpieces of his youth, among them the piano quartet in C minor.

It might well be considered an early work, however, the composer was already over forty. The opening “Allegro” is pervaded by a sense of optimism, urged on by a strong rhythmical gesture. The E-flat Major “Scherzo” opens with plucked strings and the piano making a light-hearted contribution. The sombre character of the “Adagio” provides an unexpected contrast, and that mood is taken over in the “Finale.” The asymmetrical piano accompaniment continues throughout and brings the work to an emphatic conclusion in the major key.

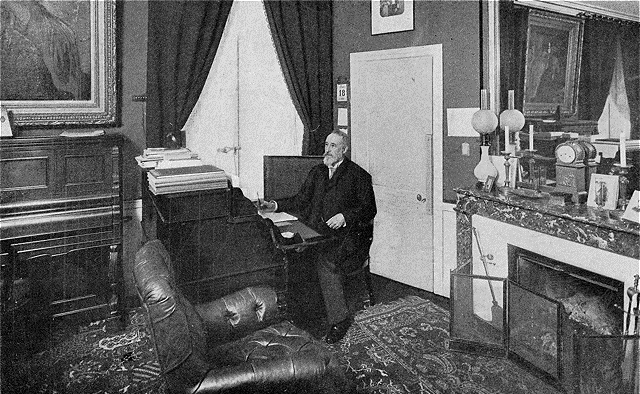

Théodore Dubois: Piano Quartet in A minor

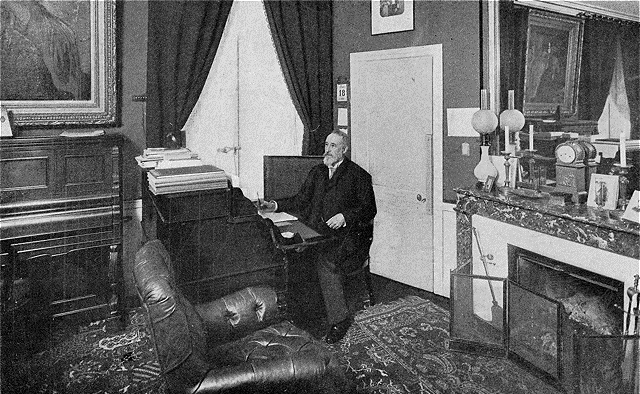

Théodore Dubois in 1905

Théodore Dubois (1837-1924) was highly influential on the French musical scene. Early on, he was known as a composer-organist with a large oeuvre of sacred music to his name. As a pedagogue, he is still famous as the author of the most common music theory textbooks, and as an administrator, he gained notoriety by denying the famed Rome prize to Maurice Ravel on multiple occasions.

Once Dubois retired from the directorship of the Conservatoire, he worked on a chamber music project. A scholar writes, “If they are not progressive works of genius, we can still enjoy their faultless design and beauty of sonority as documents to help us understand the world and spirit in Paris before, around and after 1900.”

Dubois’ piano quartet in A minor appeared in 1907 and features a conventional four-movement design. The opening “Allegro” begins with a cautious drama but quickly transitions to a lyrical melody. The sense of melodic dominance is taken over in the “Andante,” followed by an “Allegro” replacing a scherzo. Essentially a character piece in the style of Mendelssohn, it is followed by a “Finale” of sophistication and balance.

Mélanie Bonis: Piano Quartet No. 1 in B-flat Major, Op. 69

Mélanie Bonis, 1908

Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) was born into a Parisian lower-middle-class family and initially discouraged from pursuing music. Undeterred, she taught herself how to play the piano, and only at the urging of a family friend and with help from César Franck was she admitted to the Paris Conservatoire.

To conceal her gender during a time when compositions by women were not taken seriously, she shortened her first name to “Mel.” A good many of her late compositions have still not been published, and as she wrote to her daughter, “My great sorrow is that I never get to hear my music.”

Her first piano quartet was written between 1900 and 1905, and stylistically, it is cast in a post-Romantic tradition. Bonis explores the various possibilities of harmony and rhythm, infused with a dash of Impressionism. A good many passages show the influence of César Franck with long developments and rigorous counterpoint. At the work’s first performance, a surprised Camille Sain-Saëns declared, “I would never have believed a woman capable of writing that. She knows all the tricks of the trade.”

Joaquín Turina (1882-1949), together with his friend Manuel de Falla, helped to promote the national character of 20th-century Spanish music. At first, influenced and inspired by Debussy, Turina soon developed a distinctly Spanish style, “incorporating Iberian lyricism and rhythms with impressionistic timbres and harmonies.”

Jacinto Higueras Cátedra: Bust of the composer Joaquín Turina, 1971 (Madrid: Escuela Superior de Canto)

While his Op. 1 Piano Quintet in G minor emerged from his study with Vincent d’Indy, the Op. 67 piano quartet in A minor is “music without the slightest need of any explanations.” The three-movement work is carefully constructed in cyclical form, and “the juxtaposition of contrasting themes give the overall shape a rhapsodic structure.”

The fundamental musical idea is introduced in the opening movement and transformed and modified throughout the work. Of particular lively interest is the central “Lento,” where Turina transformed Andalusian elements without abandoning the gestures, temperament and uniqueness of his native lands. I hope you have enjoyed this further excursion into the realm of the piano quartet, and I can already promise one more article on the subject with music by Mozart, Taneyev, Hahn, Brahms, Copland and others.