It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, January 3, 2026

Saint-Saëns: Symphony No. 3 'Organ Symphony'

Friday, November 14, 2025

The Key Conductor: Pierre Monteux

by Maureen Buja

French conductor Pierre Monteux (1875–1964) always seemed to be the right man at the right time. As a student of violin and viola at the Paris Conservatoire, his fellow students included George Enescu, Fritz Kreisler, and Alfred Cortot. Upon graduation, one of his first jobs was violist for the orchestra of the Folies Bergère (1889–1892), when the Folies had Toulouse-Lautrec doing their posters. He played in or conducted works by Camille Saint-SaënsSaint, including being a last-minute conductor for a performance of Saint-Saëns’s cantata La Lyre et la Harpe (the composer at the organ), earning Saint-Saëns’s undying gratitude.

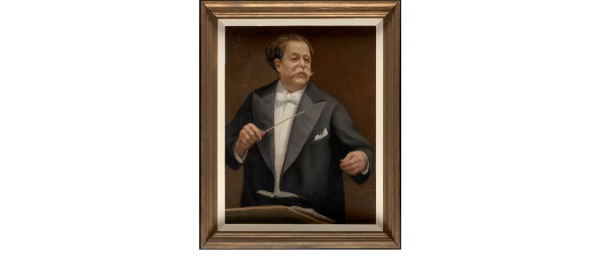

Irwin D. Hoffmann: Pierre Monteux, 1959 (Boston Public Library)

In 1894, he was named both principal violist and assistant conductor of the Colonne Orchestra in Paris. The orchestra’s founder, Édouard Colonne, had known Berlioz and could work with Monteux on what the composer really wanted in a performance of his works. His next position was as chief conductor for the seasonal Dieppe Casino orchestra (while still maintaining his Colonne positions).

In 1910, the Colonne Orchestra played for the Ballets Russes season, and Monteux met Stravinsky for the first time. He played viola for the world premiere of The Firebird in 1910, and the next year led the rehearsals for the premiere of Petrushka. He ended up conducting the premiere as well, at the insistence of the composer.

Along with impressing Saint-Saëns and Stravinsky, he also caught the eye of Claude Debussy, particularly because of his ability to rehearse and present new music. When the Colonne Orchestra was giving the world premiere of Debussy’s Images pour orchestra, it was Monteux who led the orchestral rehearsals, and Debussy conducted the premiere (26 January 1913).

After the January premiere of Images, it was onto Debussy’s ballet Jeux and then, on 29 May 1913, the infamous premiere of The Rite of Spring and riot.

With the start of WWI, Monteux was conscripted into the French Army, but Diaghilev got him released to take the Ballets Russes on tour to North America. After the war, the Boston Symphony Orchestra approached Monteux to be their new chief conductor. He only lasted 5 years there, but changed the orchestra for the better, and handed it over to Serge Koussevitzky, who would be its music director for the next 25 years.

Pierre Monteux, 1924 (Pierre Monteux Memorial Foundation Archive)

Monteux, in the meantime, went to Amsterdam, where he became the first conductor at the Concertgebouw, serving under Willem Mengelberg, the chief conductor. The other major work on this new recording is Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, written in 1931 for the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The influence of Bach on Stravinsky is palpable in the Symphony, particularly Bach’s St Matthew Passion, which had been widely played all over Europe during the work’s bicentenary in 1927.

Alfred Bendiner: Pierre Monteux (1947) (Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, Gift of Mrs. Alfred Bendiner)

Taking up his conducting career at the cusp of the 20th century, Monteux took part in some of the most exciting and controversial happenings in music, from premieres of works by Saint-Saëns to the Parisian riots over Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. He brought the Boston Symphony back to life and then went on to lead one of Europe’s great orchestras.

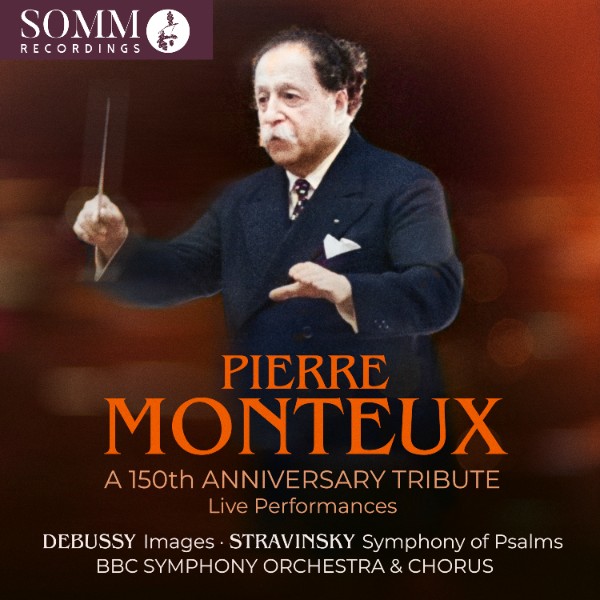

This 150th anniversary tribute to Pierre Monteux was recorded in 1961 as a live broadcast on the BBC Home Service. The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, as led by Monteux, give us the best of his repertoire in performances of works that couldn’t be further apart in style: Debussy’s orchestral Images, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms.

Pierre Monteux: 150th Anniversary Tribute: Live Performances

BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

SOMM Recordings ARIADNE 5042

Official Website

Friday, December 13, 2024

When Simple is Necessary: Fauré’s Berceuse

by Maureen Buja

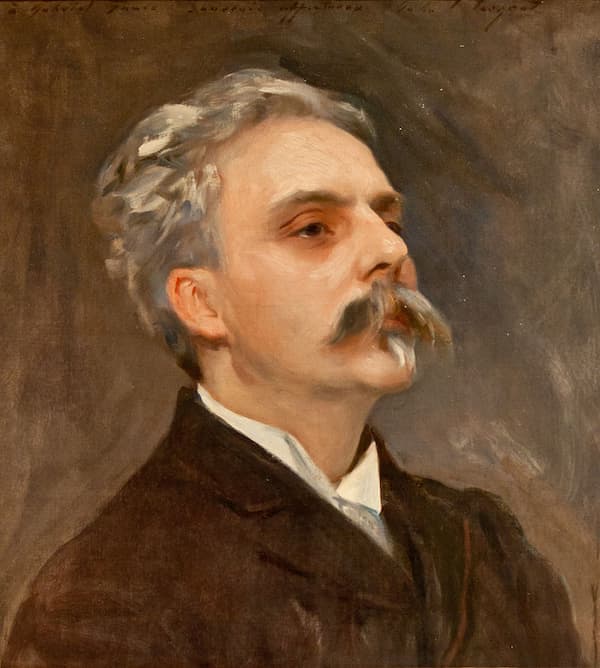

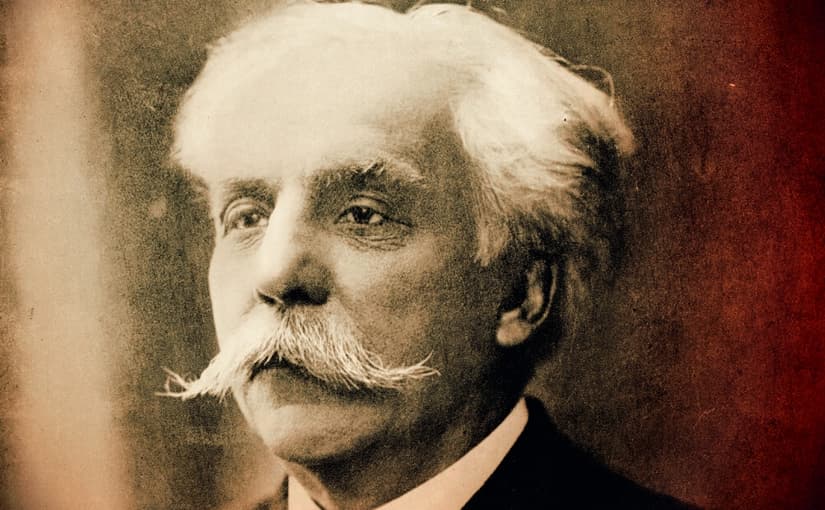

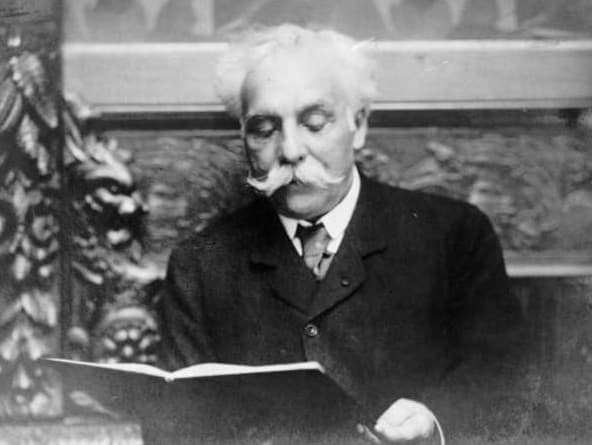

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1899 (Paris: Musée de la Musique)

Fauré made his name at two major French churches as an organist. First at the Église Saint-Sulpice, where he started as the choirmaster in 1871 under the organist Chares-Marie Widor before moving to the Église de la Madeleine in 1874, where he was deputy organist under Camille Saint-Saëns, taking over when the senior organist was on one of his frequent tours. Although he was recognised as a leading organist and played it professionally for some 40 years, he didn’t appreciate its size, with one commentator saying, ‘for a composer of such delicacy of nuance, and such sensuality, the organ was simply not subtle enough’.

In 1879, he wrote a little Berceuse that was quickly appreciated by violinists. Fauré himself didn’t quite see what the fuss was about, but the work went into the repertoire of many violinists in the late 19th century and was recorded by the great Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe.

The premiere of the work was given in February 1880 at the Société Nationale de Musique (which Fauré was a founding member) with the violinist Ovide Musin and the composer at the piano. The French publisher Julien Hamelle was at the performance and quickly put the work into print, where it sold over 700 copies in its first year alone.

It has been arranged for cello, violin and orchestra, and even as a vocalise for text-less voice and harp.

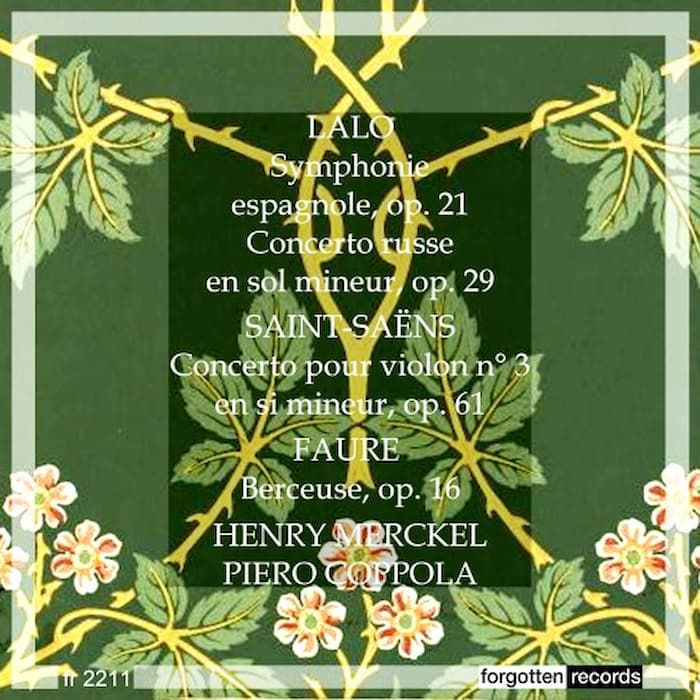

This recording was made in 1935, with violinist Henry Merckel, under Piero Coppola leading the Orchestre des Concerts Pasdeloup.

Henry Merckel

Henry Merckel (1887–1969) was a classical violinist from Belgium who graduated from the Paris Conservatoire in 1912. He had his own string quartet and was concertmaster of the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra (now known as the Orchestra de Paris) from 1929 to 1934, and also served as concertmaster of the Paris Opera Orchestra from 1930 until 1960.

Piero Coppola

The Italian conductor Piero Coppola (1888–1971) studied piano and composition at the Milan Conservatory. He graduated in 1910 and, in 1911, was already conducting at La Scala. He is known for his recordings of Debussy and Ravel in the 1920s and 1930s, including the first recordings of Debussy’s La Mer and Ravel’s Boléro, with his Debussy recordings being praised as ‘close to Debussy’s thoughts’. From 1923 to 1934, he was the artistic director of the recording company La Voix de son Maître, the French branch of The Gramophone Company, under whose name this recording was made.

The Orchestre des Concerts Pasdeloup, founded in 1861 by Jules Pasdeloup, is the oldest symphony orchestra in France. They scheduled their concerts for Sundays to catch concert-goers who weren’t able to make evening concerts. It started out with the name of Concerts Populaires and ran until 1884. It was started up again in 1919 under Serge Sandberg as the Orchestre Pasdeloup.

Performed by

Henry Merckel

Piero Coppola

Orchestre des Concerts Pasdeloup

Recorded in 1935

Friday, November 8, 2024

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) An Anniversary Cello Tribute

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Gabriel Fauré © Pianodao

Stylistic developments none withstanding, Fauré developed his individual voice from his handling of harmony and tonality. Drawing on rapid modulations, he never completely destroyed the sense of tonality, always aware of its limits, yet freeing himself from many of its restrictions.

Fauré’s harmonic richness is complemented by his melodic invention. As Jean-Michel Nectoux writes, “he was a consummate master of the art of unfolding a melody: from a harmonic and rhythmic cell he constructed chains of sequences that convey, despite their constant variety, inventiveness and unexpected turns an impression of inevitability.”

Concurrently with his songs, chamber music constitutes Fauré’s most important contribution to music. The elegance, refinement, and sensibility of his melodic writing easily transferred into the instrumental realm. On the 100th anniversary of his death, let us celebrate Fauré’s highly developed sense of sonorous beauty by exploring his magnificent and highly popular compositions for the cello.

Let’s get started with one of the most beautiful and popular pieces by Gabriel Fauré, the Sicilienne, Op. 78. The work actually has an interesting history, as Camille Saint-Saëns was asked by the manager of the Grand Théâtre to compose incidental music for a production of Molière’s “Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme.” However, Saint-Saëns was rather busy, and he recommended his former student Gabriel Fauré for the task.

Portrait of Camille Saint-Saëns by Benjamin Constant

Fauré went to work, and the music was nearly complete when the theatre company went bankrupt in 1893. The production was abandoned, and the music, including the first version of the Sicilienne, remained unperformed. Five years later, Fauré was engaged to write incidental music for the first English production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s play, Pelléas et Mélisande. Fauré would eventually publish a suite derived from this incidental music, which included an updated and orchestrated version of the Sicilienne.

Concordantly, however, the Dutch cellist Joseph Hollman, who frequently appeared in concert with Camille Saint-Saëns, was looking for a short encore. As such, Fauré fashioned an arrangement for cello and piano and dedicated the piece to William Henry Squire, a British cellist and principal with several major London orchestras. This most famous and memorable melody builds from a delightful lyrical theme in the minor mode. It evokes a pastoral mood with its lilting rhythms, and it has since been arranged for countless combinations of instruments.

The two sonatas for cello and piano by Gabriel Fauré belong to his final creative period. The first sonata was composed in Saint-Raphaël, where Fauré liked to seclude himself far away from the hustle and bustle of Paris. Written between May and October 1917, the work echoes the unsettling dark days of the First World War. To be sure, Fauré’s younger son Philippe was in the army, and the A-minor sonata seemingly reflects the composer’s anxiety and apprehension.

Fauré’s older son Emmanuel suggested that the uncharacteristically aggressive tone of the composition also represents his father’s anger at his worsening deafness. Like much of his chamber music from this period, Fauré was searching for harmonic and contrapuntal freedom, “and the rarefied and austere character is reinforced by concentrated writing for the instruments.”

Gabriel Fauré in 1907

The opening “Allegro deciso” launches into a violent theme from a discarded symphony and also from the music of his warlike opera Pénélope. The lyrical contrast is short-lived, and the fiery ending features new unsettling piano figuration. Essentially a restless nocturne, the central “Andante” was the first movement to be composed. The music offers echoes from his Requiem, and the search for tranquillity is continued in the concluding “Allegro comodo.” However, brief glimpses of optimism are subdued by strict contrapuntal severity.

Gabriel Fauré had a complicated relationship with the publisher Julien Hamelle. Hamelle was a shifty character who frequently lost manuscripts, and as he was severely “forgetful,” he was not particularly reliable. Always looking for quick sales, Hamelle loved to add fanciful titles to Fauré’s compositions. Such was certainly the case for the French “Flight of the Bumblebee” he commissioned from Fauré. This virtuoso miniature was composed in 1884 but only published fourteen years later, in 1898.

Hamelle insisted on first calling the piece Libellules (Dragonflies), then Papillon (Butterfly). Fauré was never enamoured with fanciful titles, and he angrily wrote back, “Butterfly or Dung Fly, call it whatever you like.” Fauré did insist, however, that the words “Pièce pour violoncelle,” a title more suited to his aesthetic approach, should appear as a sub-title.

Scored in five sections, it is a piece of pure virtuosity in the outer framing pillars. The middle episodes, however, contain the most beautiful lyrical passages. This gorgeous symmetrical song, as a commentator writes, “finally takes wing over one of Fauré’s favourite descending bass lines.” In the end, Hamelle was correct in appending a fanciful title as Papillon became incredibly popular with cellists from around the world.

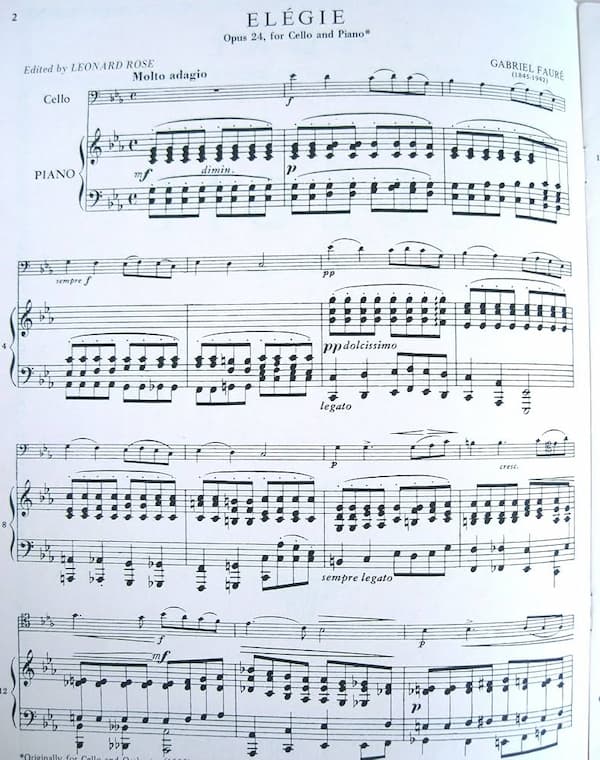

Fauré’s Papillon was actually a commissioned pendant for his already highly popular Élégie. That particular gem emerged in 1880 after the composer had finished a violin sonata. Fauré had decided to write a counterpart for the cello, and habitually, he started with the slow movement. When he played it for his friend and mentor Camille Saint- Saëns, his teacher was overjoyed. Work on the sonata progressed no further, but the slow movement with the title “Élégie” was published in 1883.

Gabriel Fauré’s Élégie, Op. 24

For Patrick Castillo, “the compact frame, its brevity, intimate scoring…belies its expressive range. The work seems to honour grief as a multifaceted thing and depicts it as such. Herein lies Fauré’s mastery. He possesses the sensibility to probe, with economy and exquisite subtlety, the depth of human emotion, giving graceful voice to our innermost feelings.”

Scored in three sections, the C-minor opening is reminiscent of a funeral march supported by a solemn progression of chords on the piano. As the middle section modulates to the major key, the music becomes more lyrical and melancholic. A sudden tortured outcry returns us to the opening melody, now transformed and supported by a flurry of notes in the piano.

The Berceuse, later to become part of the Dolly Suite, damaged Fauré’s reputation for a very long time. Let me explain. It actually dates from his student years and was composed in 1864. It was originally titled “La Chanson dans le jardin,” and written for Suzanne Garnier, the daughter of a friend. The initial scoring called for violin and piano, but once it was published, the title page provided the option “for violin or cello.” In the event, this tender little piece caused Fauré to be known as a “salon composer,” a reputation that proved incredibly difficult to shake.

When Fauré first met Emma Bardac, she had recently given birth to a daughter, Hélène, nicknamed Dolly. Emma was married to a banker and Gabriel to Marie, and their affair lasted the better part of four years. Emma was his intellectual equal; she was outgoing, amusing, articulate, and exuded great warmth from the mothering side of her personality. After their affair ended, Emma met Debussy, and after eloping to England, the two got married.

Emma Bardac-Debussy

In the 1890s, Fauré composed or revised small pieces, especially for Dolly. These pieces celebrated a birthday, a pet, or various friends of the little girl. Combining six of these miniatures, Fauré produced the “Dolly Suite” for piano duet. The Berceuse marked Dolly’s first birthday in 1893. This dreamy lullaby rocks the cradle with a swinging accompaniment, a music-box texture, and charming harmonic transparency.

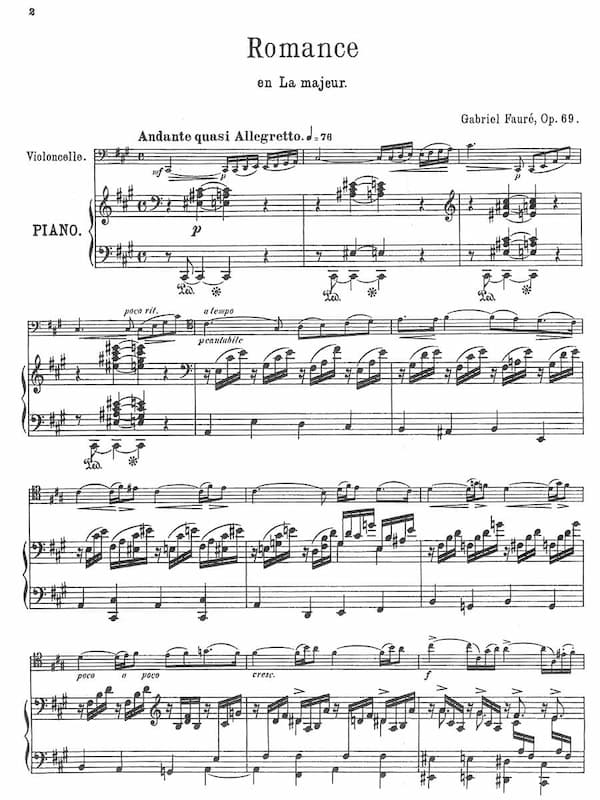

Romance

During his time as organist at the Église de la Madeleine in Paris, Fauré composed a short piece for organ and cello simply titled “Andante.” For unknown reasons, the composer delayed publication until 1894, but eventually adapted the original organ part for the piano. He changed the tempo from “Andante” to “Andante quasi allegretto” and appended the title “Romance.”

Gabriel Fauré’s Romance, Op. 69

The sustained organ chords became arpeggios, but the solo part remained essentially unchanged. This wonderful miniature places great emphasis on lyricism as the music grows into a long and flexible phrase. The principle theme is not new, as Fauré had already used it in his incidental music for Shylock, an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. And you might also recognise it from his song “Soir,” a setting of a poem by Albert Samain.

Sérénade

The last small piece for cello, chronologically, is the “Sérénade” Op. 98. Dedicated to the Catalan cellist Pablo Casals, the piece was a gift to celebrate Casal’s engagement to the Portuguese cellist Guilhermina Suggia. Never mind that the relationship never transformed into marriage. Casals was enthused about the music as he wrote to the composer, “The Serenade! It is delightful every time I play it; it seems new, so beautiful, is it.” For a variety of obvious personal reasons, Casals neither performed the piece in public nor recorded it during his long career.

The “Sérénade” unfolds as an uneasy conversation between the two instruments. The cello line presents a delightful melody akin to the best of Fauré’s songs. However, the piano part is more than just mere accompaniment, interweaving melodic lines and unsettled harmonies. It immediately interrupts the lyrical seductiveness of the melody with arpeggio figuration before taking it over completely. Despite its brevity, the “Sérénade” is surprisingly complex, painfully avoiding rhythmic and harmonic resolutions.

Cello Sonata No. 2

Fauré has almost completely lost his hearing when he started work on his 2nd Cello Sonata, Op. 117. Actually, he was commissioned by the French government to write a funeral march for a military band for a ceremony to be held on 5 May 1921. That particular date marked the 100th anniversary of the death of Napoleon. The sombre theme he composed for the occasion remained in his mind and, as he said, “turned itself into a sonata.”

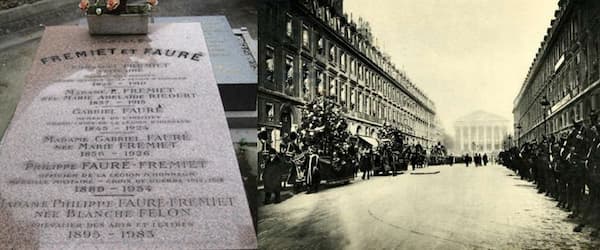

Gabriel Fauré’s grave and funeral

The reworked funeral march takes its place as the central “Andante” in the Sonata, exuding a relaxed tranquillity reminiscent of the mood presented in his Elegy, Op. 24. This sense of nostalgia is prefaced by an essentially lyrical opening movement that features two contrasting themes intertwined in free counterpoint. Jean-Michel Nectoux regarded the joyful finale “as one of the great Fauréan scherzos,” which sounds like an ode to life, “a moving profession of faith from an old man who knows that the end was approaching.”

Vincent d’Indy expressed his admiration for his friend’s work: “I want to tell you that I’m still under the spell of your beautiful Cello Sonata… The Andante is a masterpiece of sensitivity and expression, and I love the finale, so perky and delightful… How lucky you are to stay young like that!” Fauré continued to search for the purpose of music and wrote, “And what music really is, and what exactly I am trying to convey. What feeling? What ideas? How can I explain something that I myself cannot fathom?”

Fauré died from pneumonia on 4 November 1924 in Paris at the age of 79. His last words questioned, “Have my works received justice? Have they not been too much admired or sometimes too severely criticized? What if my music will live? But then, that is of little importance.” Fauré would certainly be delighted to know that his compositions for the cello are still performed with great enthusiasm and regularity. They beautifully reflect Fauré’s final thoughts that “music exists to elevate us above everyday existence.”

Friday, September 27, 2024

10 More Dazzling and Awe-Inspiring Piano Quartets

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

As a quick recap, you get a piano quartet when you add a piano to a string trio. The standard instrument lineup for this type of chamber music pairs the violin, viola, and cello with the piano. In its development, the piano quartet had to wait for technical advances of the piano, as it had to match the strings in power and expression.

© serenademagazine.com

Piano quartets are always special because the scoring allows for a wealth of tone colour, occasionally even a symphonic richness. The combined resources of all four instruments are not easy to handle, and the number of works in the genre is not especially large. However, a good many of the extant piano quartets are very personal and passionate statements.

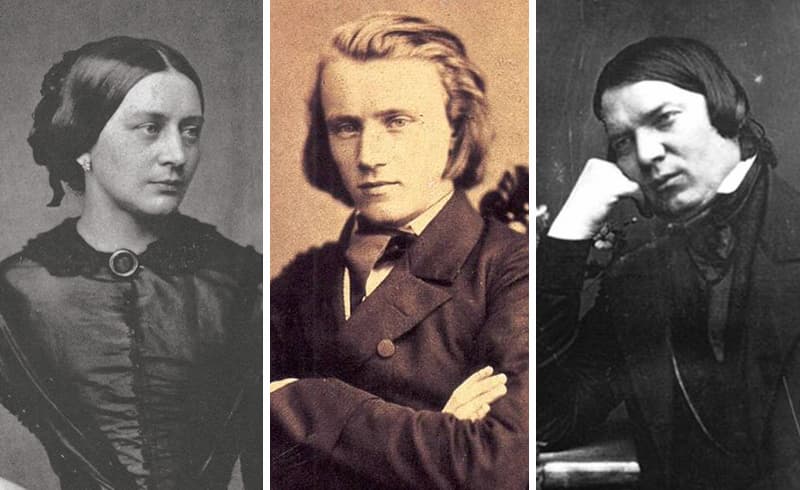

When talking about chamber music, and specifically chamber music with piano, it is difficult to avoid Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Lucky for us, Brahms wrote three piano quartets, and his Op. 60 took its inspiration from his intense relationship with Clara Schumann. However, it took Brahms almost twenty years to complete the work. The origins date back to around 1855 when Brahms was wrestling with his first piano concerto.

Brahms put this particular piano quartet aside and only showed it to his first biographer in the 1860s with the words, “Imagine a man who is just going to shoot himself, for there is nothing else to do.” Thirteen years later, Brahms took up the work and radically revised it. He probably wrote a new “Andante” and also a new “Finale.” In the end, the work finally premiered on 18 November 1875 with Brahms at the piano and the famous David Popper on cello.

Brahms and the Schumanns

The emotional distress of his relationship with Clara is presented in a mood of darkness and melancholy. A solitary chord in the piano initiates the opening movement, with the string presenting a theme built from a striking two-note phrase. Some commentators have suggested that Brahms is musically speaking the name “Clara” in this two-note phrase. The second theme is highly lyrical but quickly develops towards the dark mood of the opening. The “Scherzo” is also in the minor key, and the deeply felt slow movement is a declaration of love for Clara. The dark opening returns in the final movement, and while the development presents some relief, the work still ends on a note of resignation, albeit in the major key.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

The intensely emotional and meticulously crafted compositions by Brahms served as models for a number of composers, among them Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900). As he writes, “Brahms helped me, by the mere fact of his existence, to my development, my inward looking up to him, and with his artistic and human energy.” While Brahms respected Herzogenberg’s technical craftsmanship and musical knowledge, he never really had anything to say.

Herzogenberg was undeterred and never stopped composing. In 1897, he wrote to Brahms, “There are two things that I cannot get used not to doing: That I always compose, and that when I am composing I ask myself, the same as thirty-four years ago, ‘What will He say about it?’ To be sure, for many years, you have not said anything about it, which is something that I can interpret as I wish.”

A few days before Brahms’ death, Herzogenberg presented him with his probably best and most mature work, the Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95. The gripping “Allegro” is full of unmistakably Brahmsian character, constructed with compositional economy. An introductory chord develops into the motific core of the entire movement. The “Adagio is full of dreamy intimacy, while the capricious “Scherzo” eventually transports us into a pastoral idyll. Three themes, including a folkloric principle theme, combine in a spirited and temperamental “Finale.”

When Richard Strauss (1864-1949) left college and moved to Berlin to study music at the age of 19, he suddenly discovered a new model in Johannes Brahms. Strauss would meet his current idol personally at the premiere of Brahms’ 4th Symphony in 1885. Under the influence of Brahms, the teenaged Strauss completed his Piano Quartet in C minor in 1884, and a good many commentators believe it to be Strauss’ “greatest chamber work.”

Richard Strauss

Op. 13 is a large work fusing “the sobriety and grandeur of Brahms with the fire and impetuous virtuosity of the young Strauss.” The work opens quietly, and the deceptively simple motif returns in various disguises. However, the music quickly explodes with superheated energy, and its dark sonorities and dramatic scope drive it to a virtually symphonic close.

Finally, the “Andante” introduces a measure of calm, with the piano sounding a florid melodic strain that gives way to a lyrical second subject in the viola. Both themes are gracefully extended while bathing in a delicate and charmed atmosphere. The concluding “Vivace” returns to the mood of the opening movement, and the rondo design also features a serious refrain and a spiky fugato. The work won a prize from the Berlin Tonkünstler, Strauss, however, would say goodbye to chamber music and explore orchestral virtuosity in his great tone poems.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) seems another surprising entry into a blog on the piano quartet. However, a single movement from his student days at the Vienna Conservatory does survive. Mahler took piano lessons from Julius Epstein and studied composition and harmony under Robert Fuchs and Franz Krenn. Mahler left the Conservatory in 1878 with a diploma but without the coveted and prestigious silver medal given for outstanding achievement.

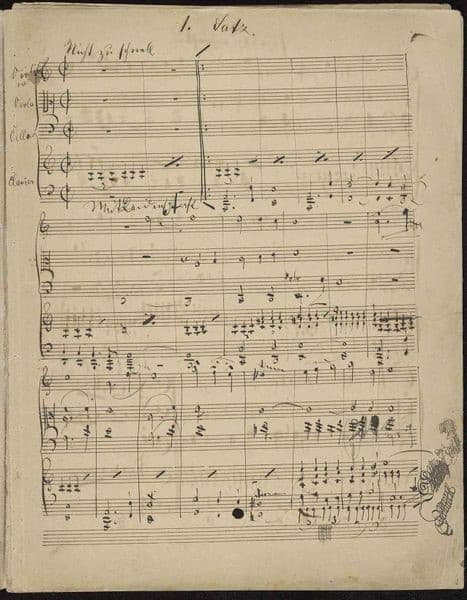

Gustav Mahler’s Piano Quartet

Although he claimed to have written hundreds of songs, several theatrical works, and various chamber music compositions, only a single movement for a Piano Quartet in A minor survived the ravages of time. Composed in 1876 and awarded the Conservatory Prize, it is strongly influenced by the musical styles of Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms.

Conveying a sense of passion and longing, Mahler presents three contrasting themes within a strict formal design. The opening theme possesses an ominous and foreboding character, while the contrasting second—still in the tonic key—is passionately rhapsodic. To compensate for this tonal stagnation, the third theme undergoes a series of modulations. Thickly textured and relying on excessive motivic manipulation, this movement nevertheless provides insight into the creative processes of the 16-year-old Mahler.

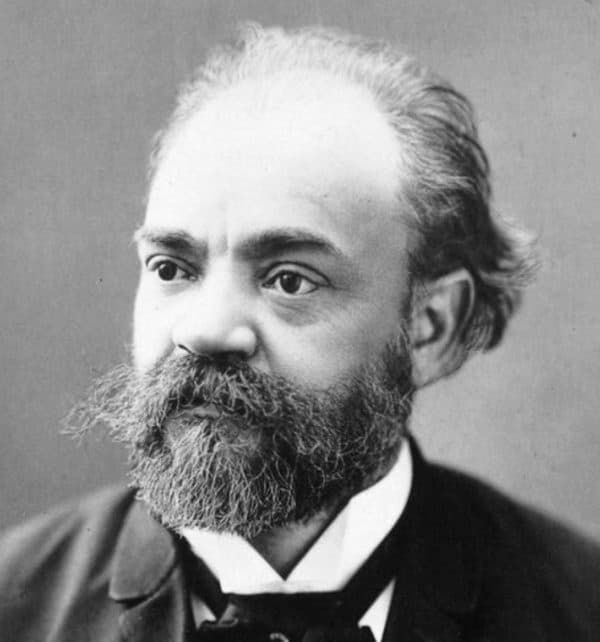

Antonín Dvorák (1841-1904) is another composer who, for a time, took his bearings from Johannes Brahms’s music. Dvorák had always been strongly drawn to chamber music, as his first published works are a string quartet Op. 1 and a string quintet Op. 2.

Dvořák in New York, 1893

Apparently, he composed his D-Major piano quartet in a mere eighteen days in 1875. It premiered five years later, on 16 December 1880. Surprisingly, this piano quartet has only three movements, as the composer combines a scherzo and Allegro agitato in alternation in the Finale. The opening “Allegro” sounds like a rather characteristic Czech melody, initiated by the cello and continued by the violin. By the time the piano takes up the theme, the tonality has shifted to B Major.

The melody of the slow movement, a theme followed by five variations, is introduced by the violin. Dvorák skillfully presents fragments of the theme in various meters and textures. The cello, accompanied by the piano, takes the lead in the final “Allegretto.” After the violin has taken up the theme, the piano takes us into the finale proper.

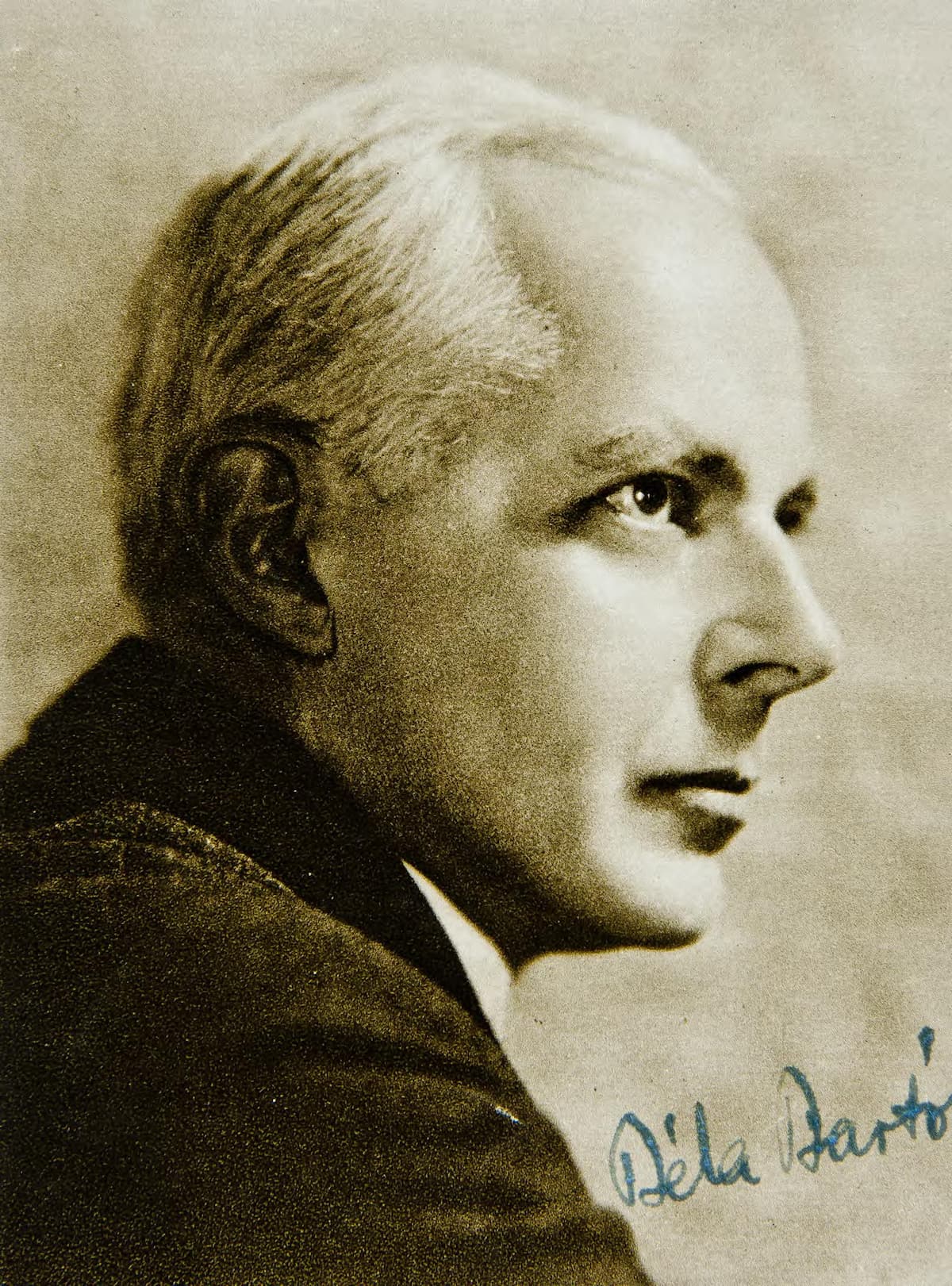

Béla Bartók: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 20

Béla Bartók

To his contemporaries and critics, Johannes Brahms looked like a bastion of musical conservatism. Surprisingly, it was Arnold Schoenberg, in his celebrated Radio address entitled “Brahms the Progressive”, who suggested that Brahms was “a great innovator in the realm of musical language and that his chamber music prepared the way for the radical changes in musical conception at the turn of the 20th century.”

Just one year after Brahms’ death, the teenage Béla Bartók (1881-1945) embarked on the composition of a four-movement piano quartet. For years, this score was believed to have been lost, but it was rediscovered by a member of the “Notos Quartet,” who also prepared the edition following the composer’s autograph score. What is more, they also presented a world premiere recording in 2007.

The opening “Allegro” immediately evokes the harmonic and sensuous soundscape of Johannes Brahms. And like his model, Bartók’s musical prose does not follow a predictable pattern as the boundaries and distinctions of theme and development are blurred. Brahms’ rhythmic shapes are the topic of a blazing “Scherzo,” with the “Trio” sounding a sombre lyrical contrast. The “Adagio” sounds like a declaration of love for Brahms, while the “Finale” brims with spicy Hungarian flavours.

Camille Saint-Säens introduced Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) to Pauline Viardot in 1872. Her youngest daughter, Marianne, immediately stole his heart, and Fauré courted her for four painful years. In July 1877, she finally agreed, and the engagement was announced. However, the relationship only lasted until the late autumn of 1877, when Marianne suddenly broke off the engagement.

Pauline Viardot

The exact reasons remain unclear, and Fauré was deeply distressed, with friends reporting that his “sunny disposition took a dark turn.” He started to suffer from bouts of depression, and the Clerc family helped him to recover. At this point, Fauré composed the masterpieces of his youth, among them the piano quartet in C minor.

It might well be considered an early work, however, the composer was already over forty. The opening “Allegro” is pervaded by a sense of optimism, urged on by a strong rhythmical gesture. The E-flat Major “Scherzo” opens with plucked strings and the piano making a light-hearted contribution. The sombre character of the “Adagio” provides an unexpected contrast, and that mood is taken over in the “Finale.” The asymmetrical piano accompaniment continues throughout and brings the work to an emphatic conclusion in the major key.

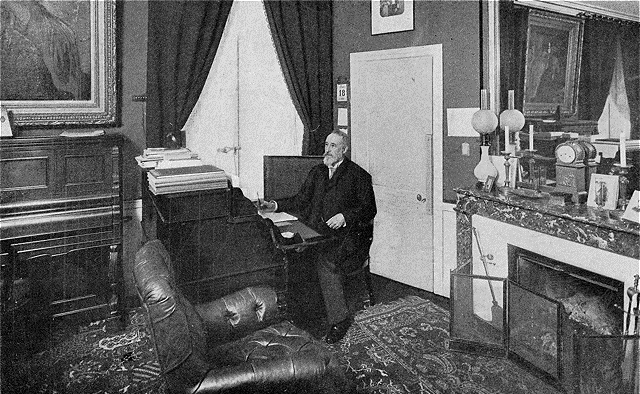

Théodore Dubois: Piano Quartet in A minor

Théodore Dubois in 1905

Théodore Dubois (1837-1924) was highly influential on the French musical scene. Early on, he was known as a composer-organist with a large oeuvre of sacred music to his name. As a pedagogue, he is still famous as the author of the most common music theory textbooks, and as an administrator, he gained notoriety by denying the famed Rome prize to Maurice Ravel on multiple occasions.

Once Dubois retired from the directorship of the Conservatoire, he worked on a chamber music project. A scholar writes, “If they are not progressive works of genius, we can still enjoy their faultless design and beauty of sonority as documents to help us understand the world and spirit in Paris before, around and after 1900.”

Dubois’ piano quartet in A minor appeared in 1907 and features a conventional four-movement design. The opening “Allegro” begins with a cautious drama but quickly transitions to a lyrical melody. The sense of melodic dominance is taken over in the “Andante,” followed by an “Allegro” replacing a scherzo. Essentially a character piece in the style of Mendelssohn, it is followed by a “Finale” of sophistication and balance.

Mélanie Bonis: Piano Quartet No. 1 in B-flat Major, Op. 69

Mélanie Bonis, 1908

Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) was born into a Parisian lower-middle-class family and initially discouraged from pursuing music. Undeterred, she taught herself how to play the piano, and only at the urging of a family friend and with help from César Franck was she admitted to the Paris Conservatoire.

To conceal her gender during a time when compositions by women were not taken seriously, she shortened her first name to “Mel.” A good many of her late compositions have still not been published, and as she wrote to her daughter, “My great sorrow is that I never get to hear my music.”

Her first piano quartet was written between 1900 and 1905, and stylistically, it is cast in a post-Romantic tradition. Bonis explores the various possibilities of harmony and rhythm, infused with a dash of Impressionism. A good many passages show the influence of César Franck with long developments and rigorous counterpoint. At the work’s first performance, a surprised Camille Sain-Saëns declared, “I would never have believed a woman capable of writing that. She knows all the tricks of the trade.”

Joaquín Turina (1882-1949), together with his friend Manuel de Falla, helped to promote the national character of 20th-century Spanish music. At first, influenced and inspired by Debussy, Turina soon developed a distinctly Spanish style, “incorporating Iberian lyricism and rhythms with impressionistic timbres and harmonies.”

Jacinto Higueras Cátedra: Bust of the composer Joaquín Turina, 1971 (Madrid: Escuela Superior de Canto)

While his Op. 1 Piano Quintet in G minor emerged from his study with Vincent d’Indy, the Op. 67 piano quartet in A minor is “music without the slightest need of any explanations.” The three-movement work is carefully constructed in cyclical form, and “the juxtaposition of contrasting themes give the overall shape a rhapsodic structure.”

The fundamental musical idea is introduced in the opening movement and transformed and modified throughout the work. Of particular lively interest is the central “Lento,” where Turina transformed Andalusian elements without abandoning the gestures, temperament and uniqueness of his native lands. I hope you have enjoyed this further excursion into the realm of the piano quartet, and I can already promise one more article on the subject with music by Mozart, Taneyev, Hahn, Brahms, Copland and others.