Alma Rosé

Alma Rosé, a top-class artist – violinist, conductor, ensemble leader and actress, is most remembered today for her amazing courage. She was the conductor and founder of the celebrated women’s orchestra Wiener Walzermädeln–but she is primarily remembered as the conductor of the infamous women’s orchestra in the Nazi death camp Auschwitz. While she kept her musicians alive, she tragically perished.

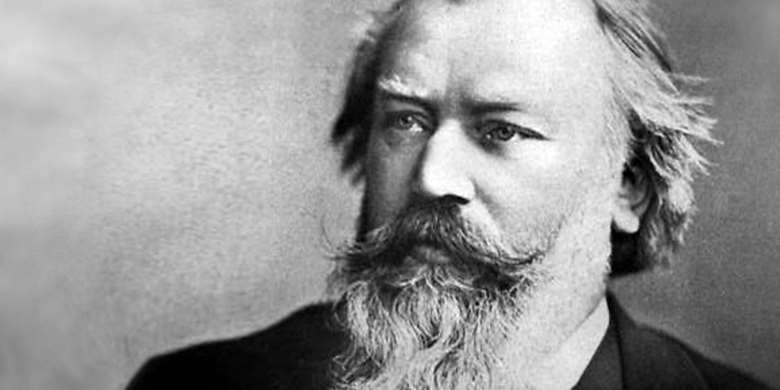

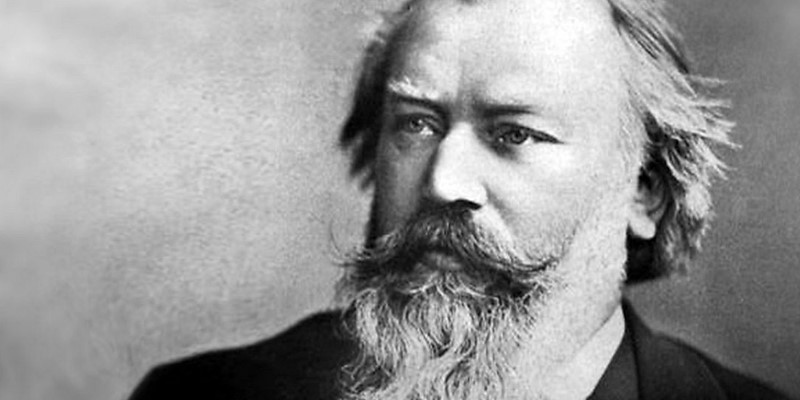

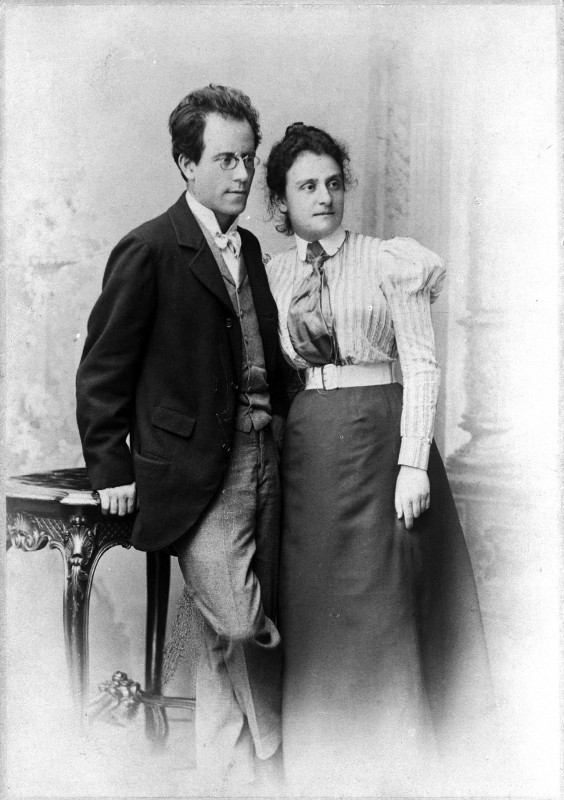

Gustav Mahler

Justine and Gustav Mahler

Alma came from musical royalty: Alma’s mother, Justine Mahler, was the younger sister of legendary composer Gustav Mahler. As Mahler’s niece, she had contact with and was surrounded by the musical stars of early 20th-century Germany and Vienna. Her father, violinist Arnold Rosenblum, also a great influence, was the concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic.

Gustav Mahler and Arnold Josef Rosé

To be accepted in Vienna into the upper echelons of society, it was not advantageous to be Jewish. Rosé Austrianized his name from Rosenblum to Rosé in 1882. Mahler also felt he had to convert, and he did so in 1897 to Catholicism.

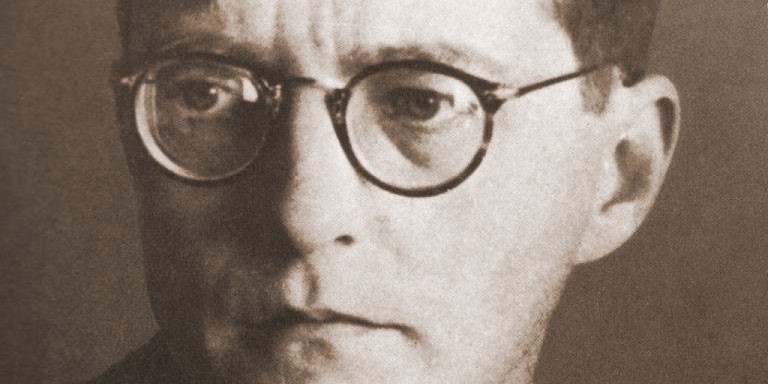

The young Alma Rosé

Rosé, a superb violinist, founded and performed with the internationally renowned Rosé String Quartet. The Rosé quartet gave premieres of both Brahms and Schoenberg. That’s an indication of the group’s longevity, and we are fortunate to have a recording from 1910, albeit a bit scratchy!

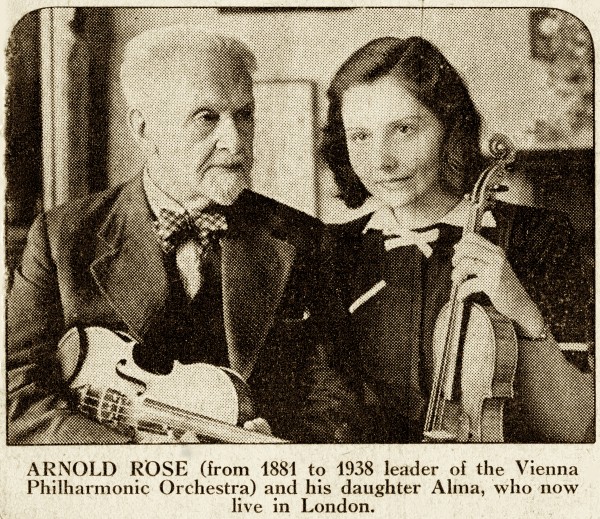

Alma and Arnold Rosé, Date unknown © Gustav Mahler–Alfred Rosé Collection, Music Library, Western University, London, Canada

Arnold was Alma’s first teacher, and soon Alma was proficient enough to make her Viennese debut in 1926, at the Musikverein, playing Bach‘s Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043 as a soloist performing with her father. We can hear them together playing the Largo movement on this rare recording from 1928. There are no other known sound recordings of Alma.

In 1930, at the age of 24, Alma married the brilliant young Czech violinist Váša Příhoda and took Czechoslovakia citizenship. Alma hoped to stand out from the shadow of the two great violinists in her life, her father and her husband. She established something different, founding a touring women’s orchestra in 1932. The nine to fifteen-member Wiener Walzermädeln (Viennese Waltzing Girls) donned elegant and feminine matching gowns, sometimes wearing charming caps, and played the most popular music of the time, the Viennese waltz. Austria had become synonymous with the waltz, a popular genre in the 1800s and homeland of the Waltz King, Johann Strauss II. The Walzermädeln toured with enormous success all throughout Europe in the early 30s.

The Viennese Waltz Girls (Bottom: Alma Rosé standing) 1933

© Gustav Mahler–Alfred Rosé Collection, Music Library, Western University, London, Canada

Alma Rosé as a young girl around 1914 © Gustav Mahler–Alfred Rosé Collection, Music Library, Western University, London, Canada

The music they would’ve played includes Johann Strauss’s charming waltzes, marches, and polkas such as Artists Waltz Op.316, his Persian March Op. 289 and his Champagne Polka Op. 211.

The group continued to perform all over Europe, from Warsaw to Rome, until the political climate in Austria became increasingly alarming, when Hitler came to power in Germany. The last concert of the Viennese Waltzing Girls was at Vienna’s Ronacher Theater on New Year’s Eve 1937, bringing their performances to an end. Only a few weeks later, the Nazi “Anschluss” (annexation) of Austria took place in March 1938. The Rosé family members were immediately barred from performing. Alma’s father, after 57 years, was removed from positions at both the Opera and the Vienna Philharmonic, ignominiously ousted.

As Jews, the Rosé family understood the serious risks to their family. During the troubling years of the 1930s, they’d felt helpless, as Alma’s mother, Justine, Mahler’s sister, was gravely ill. When she died in the late summer of 1938, they began to formulate a plan to escape.

Alma’s brother Alfred and his wife Maria Rosé-Schmutzer fled shortly afterwards, a complicated getaway via the Netherlands, then by ship to New York, finally arriving in London, Ontario, Canada.

Alma stayed behind to care for her father. Here is an extraordinary documentary to listen to.

By April 26, 1938, the Regulation on the Registration of the Assets of Jews was put into place. All Jewish people, as well as non-Jewish partners in so-called Mischehen (mixed marriages), were forced to declare their assets if they exceeded RM 5,000. The Rosé family, prominent members of society, were targeted by the Nazis. What would become of their violins? Arnold owned a rare 1718 Stradivarius and Alma, an exquisite Guadagnini from 1757.

Alma and Arnold Rosé with their violins, Atelier Willinger, undated © KHM-Museumsverband, Theatermuseum

Alma couldn’t risk the confiscation of the violins by the Nazis, but to conceal such valuable assets was a huge risk, especially for well-known personalities. It would require courageous action, clear-headed thinking, and a foolproof scheme to save them.

Undaunted, Alma’s declaration listed both violins, but their pedigree was cleverly hidden. She filled out the required document, “two Italian violins for personal use”, without the names of the makers of the instruments, which would have immediately revealed their value.

The ploy worked. It helped enormously that Alma’s Czech married name and her Czechoslovakian citizenship disguised who she truly was, a critical factor that contributed to a successful flight from the Nazis.

Alma fled to London in early 1939. Arnold followed her a few weeks later at the last possible moment before the borders were tightly closed. After such an incomparable and illustrious career, Arnold was forced to leave Austria penniless.

Once they’d escaped, they were plagued by financial problems that became overwhelming. The refugees flocking to London, mainly European musicians, were barred from performing and teaching. Alma succeeded in taking both instruments with her, but as hunger became a constant, the Rosés adamantly refused to sell their violins.

In desperation, Alma signed a contract for a two-month engagement at the Grand Hotel Central in The Hague – a venue where she and the Wiener Walzermädeln had performed with great success. Alma played several house concerts and extended her stay as additional engagements opened up for her in the Netherlands.

For a few months, she was able to resume her successful concert life. But the Germans occupied the Netherlands in May of 1940. The enemies were once again at her heels. Alma and Příhoda had divorced in 1935, and she’d married Constant August van Leeuwen Boomkamp, a medical student, to continue to evade detection.

It didn’t help Alma. This time, she was trapped. Alma was arrested at a train station in France and sent to Drancy for several months. Established in August 1941, the Drancy camp in France became a major transit camp for the deportations of Jews from France. Almost 65,000 Jews were deported from Drancy to terrifying destinations, including Auschwitz. Fewer than 2,000 of them survived.

On July 18, 1943, Alma was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Almost immediately, she was sent to the dreaded and horrifying medical experimentation block—Block 10. She’d been registered under her husband’s name, so once again, Nazi officials did not realise who she was.

Fortuitously, a request was made for a violinist for a VIP’s birthday celebration in the camp. The Nazis, after all, loved their music. She played for them, and her virtuosity quite impressed the officials.

They transferred Alma to Birkenau and, in August 1943, selected her to be the conductor of the women’s orchestra.

Alma seemed to have no fear of the SS guards who respected her musicianship. Taking advantage of her position, Alma requested and somehow managed some privileges.

Her orchestra received a special barracks, which contained an unheard-of living and practicing area, with a small heater. The dwelling even had a wooden floor! Alma convinced the authorities that the instruments had to be protected against the cold and dampness. Downright luxurious compared to the bare barracks of others.

Alma began to work tirelessly on the ensemble’s quality. The group was made up of mostly amateurs who played a wide array of instruments, including violin, accordion, flute, guitars, and mandolins. Alma endeavoured to keep the players with less talent on as assistants rather than dismissing them, which was a life-saving gesture in the context of Auschwitz.

Rosé was a strict and thorough taskmistress, pushing her musicians to the limits of their endurance. It was paramount to do everything she could to make them sound professional, because the Nazis knew their music. Alma couldn’t risk mediocrity. The women rehearsed daily for eight hours a day, thereby evading the slave labour workforce.

The SS required the orchestra to play daily at the camp gates as prisoners departed for and arrived from slave labour morning and evening, and when captives were marched to the crematoriums.

The Auschwitz orchestra also performed regular Sunday concerts for selected prisoners and the camp staff; they made regular visits to the infirmary, played during elite visits to the camp, and had to be available for individual SS demands like birthday parties.

Although Alma drove herself and the musicians, she was respected by her orchestra, valued for both her violin playing and her conducting. Above all, she understood that if they were to survive, they had to please the SS. Surely, if they played well enough, they would be allowed to live.

Drawing of Alma Rosé in Auschwitz

Rosé arranged pieces for her orchestra from whatever sheet music she had available and from melodies she recalled from memory: music by Mozart, Schubert, Vivaldi, Johann Strauss, and Franz Liszt, and from German hits, movie and operetta tunes.

Playing music gave them all moments of respite, allowing them to float somewhere above or beyond the camp atmosphere.

Alma Rosé’s final concert was at a private SS party on April 2, 1944.

Suddenly and inexplicably ill, she was taken to the infirmary with head and stomach pains and a high fever. On 4 April 1944, she was declared dead. There are still questions about her death. Could it have been suicide or poisoning by jealous functionaries? Many insist that she fell victim to accidental food poisoning or a sudden infection.

Unbelievably enough, the SS approved an observance in her memory —to recognise her unique status, perhaps the only time in the history of the camps that SS officers honoured a dead Jewish prisoner.

For the musicians, however, their grief was mixed with fear. Former member Silvia Wagenberg remembered:

When she died, I thought, now it’s over; either they will send us somewhere else — then we’re done for, or we’ll be gassed right away. It is hardly measurable what Alma meant for the orchestra.”

All but two of the orchestra members survived the war. Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, a cellist, was one of them, saved by playing in the Auschwitz women’s orchestra.

When the war was finally over, Lasker-Wallfisch settled in Britain, where she met and married her husband, Peter Wallfisch. She was the founding member of the British Chamber Orchestra, touring internationally with the group. Anita refused to go to Germany for many decades until in 1994, she realised she must relate her experiences during the war.

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, now 100 years old. She has eloquently related her experiences in numerous documentaries about her life. Two poignant things she’s said jump out for me: “As Long as We Can Breathe, We Can Hope,” and “Music takes you out into a different sphere. You get away from your horrible realities…You could lose yourself in music, untouchable.”

Please listen to two short examples of Lasker-Wallfisch’s testimonies.

The piece that is featured in this clip by the BBC, Robert Schumann’s Träumerei is ironically enough, from his “Scenes from Childhood”, this movement is entitled “Dreaming.”

It is deeply troubling that Alma perished alongside so many millions. It’s impossible to imagine that under these horrific circumstances, musical ensembles were established in several concentration camps, including an orchestra that my father joined after being liberated. Somehow, the musicians continued to perform, and music saved their lives.

Even after the war, music enabled survivors to build a new life. My father was one of them. A cellist too, after months as a slave labourer in the copper mines of Bor, Yugoslavia, my father played 200 concerts from 1946-1948 in a 17-member orchestra in the displaced persons camps throughout Bavaria. Their mandate—to bring morale-boosting programs to those still languishing in DP camps waiting for news of loved ones or the right paperwork to leave Europe. In 1948, two of the concerts my father played in Landsberg, Germany, were with Leonard Bernstein performing and conducting, before he was as famous as he was to become.

If you’d like to read more about these times, I tell our family story in my book The Cello Still Sings – A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music.

There’s a wonderful book about Alma Rosé by Richard Newman, Alma Rosé: Vienna to Auschwitz, and watch for a new documentary now in production, Alma Rosé, directed and produced by Francine Zuckerman of z films. (More details from @almarosefilm)