Today, we’re looking at love letters from ten composers, including Mozart being very saucy on a business trip, Brahms pining over Clara Schumann, and Haydn making a shocking confession to his mistress.

Joseph Haydn, 1791

Joseph Haydn

In these two love letters to his mistress, singer Luigia Polzelli, Haydn writes about her husband’s fatal illness…and longs for “four eyes [to] be closed”, a reference to his hope that his own wife will die, too!

London, 14th March 1791

Most esteemed Polzelli,

I am very sorry for you in your present circumstances, and I hope that your poor husband will die at any moment; you did well to put him in the hospital, to keep him alive…

London, 4th August 1791

Dear Polzelli!

…As far as your husband is concerned, I tell you that Providence has done well to liberate you from this heavy yoke, and for him, too, it is better to be in another world than to remain useless in this one. The poor man has suffered enough. Dear Polzelli, perhaps, perhaps the time will come, when we both so often dreamt of, when four eyes shall be closed. Two are closed, but the other two – enough of all this, it shall be as God wills.

Learn more about why Haydn hated his wife so much.

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1812

Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, finished in 1812

In 1812, Beethoven wrote an impassioned love letter to an unknown woman. This letter has come to be known as the letter to the Immortal Beloved.

Beethoven in 1803

Though still in bed, my thoughts go out to you, my Immortal Beloved, now and then joyfully, then sadly, waiting to learn whether or not fate will hear us – I can live only wholly with you or not at all – Yes, I am resolved to wander so long away from you until I can fly to your arms and say that I am really at home with you, and can send my soul enwrapped in you into the land of spirits – Yes, unhappily it must be so – You will be the more contained since you know my fidelity to you. No one else can ever possess my heart – never – never – Oh God, why must one be parted from one whom one so loves. And yet my life in V is now a wretched life – Your love makes me at once the happiest and the unhappiest of men – At my age I need a steady, quiet life – can that be so in our connection? My angel, I have just been told that the mail coach goes every day – therefore I must close at once so that you may receive the letter at once – Be calm, only by a calm consideration of our existence can we achieve our purpose to live together – Be calm – love me – today – yesterday – what tearful longings for you – you – you – my life – my all – farewell. Oh continue to love me – never misjudge the most faithful heart of your beloved. ever thine, ever mine, ever ours…

Read more about Who was the Immortal Beloved?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1783

Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail overture

Here’s a suggestive love letter from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to his wife Constanze, written in 1783 when he was about to return home to Vienna after overseeing a production of his opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail in Prague.

On June 1st I’ll sleep in Prague, and on the 4th – the 4th? – I’ll be sleeping with my dear little wife; – Spruce up your sweet little nest because my little rascal here really deserves it, he has been very well behaved, but now he’s itching to possess your sweet [word erased by some unknown hand]. Just imagine that little sneak, while I am writing, he has secretly crept up on the table and now looks at me questioningly; but I, without much ado, give him a little slap – but now he is even more [word erased by some unknown hand]; well, he is almost out of control, the scoundrel.

Find out what life was like with the Mozarts in the 1780s.

Hector Berlioz, 1832

Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique

Berlioz wrote this letter to actress Harriet Smithson, a woman whom he had been obsessed over and stalking for years, for whom he had composed the Symphonie fantastique and Lélio. He was begging her to return his letter:

Harriet Smithson in Romeo and Juliet

If you do not desire my death, in the name of pity (I dare not say of love) let me know when I can see you. I cry mercy, pardon on my knees, between my sobs!!! Oh, wretch that I am, I did not think I deserved all that I suffer, but I bless the blows that come from your hand, await your reply like the sentence of my judge.

Learn more about the insane love story between Hector and Harriet.

Franz Liszt, 1834

Liszt’s Liebestraum No. 3

In 1834, Franz Liszt wrote this to his new mistress, Countess Marie d’Agoult:

Marie d’Agoult in 1861

My heart overflows with emotion and joy! I do not know what heavenly languor, what infinite pleasure, permeates it and burns me up. It is as if I had never loved!!! Tell me whence these uncanny disturbances spring, these inexpressible foretastes of delight, these divine tremors of love. Oh! All this can only spring from you, sister, angel, woman, Marie! All this can only be, is surely nothing less than a gentle ray streaming from your fiery soul, or else some secret poignant teardrop which you have long since left in my breast.

Learn more about the passionate nature of Liszt and Marie d’Agoult’s early relationship.

Robert Schumann, 1837

Robert Schumann

In December 1837, composer Robert Schumann was in love with virtuoso pianist Clara Wieck. They’d gotten engaged a few months earlier and were doing their best to navigate their relationship, given that Clara’s father didn’t approve of their romance.

New Year’s Eve, 1837, after 11 p.m.

I have been sitting here for a whole hour. Indeed, I meant to spend the whole evening writing to you, but no words would come. Sit down beside me now, slip your arm round me, and let us gaze peacefully, blissfully, into each other’s eyes…

How happy we are, Clara! Let us kneel together, Clara, my Clara, so close that I can touch you, in this solemn hour.

On the morning of the 1st, 1838.

What a heavenly morning! All the bells are ringing; the sky is so golden and blue and clear – and before me lies your letter. I send you my first kiss, beloved.

Learn more about the brutal court case between Robert, Clara, and her father.

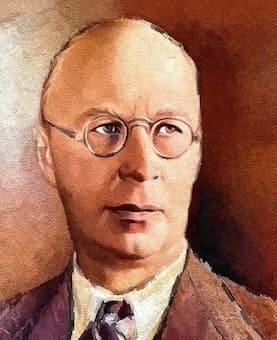

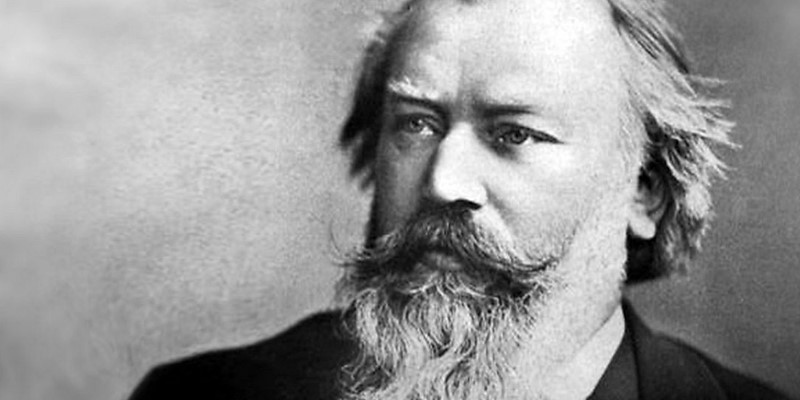

Johannes Brahms, 1858

Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1, Movement 2 (he once told Clara this was a portrait of her)

Brahms had complicated feelings for his mentor and dear friend Clara Wieck Schumann.

In 1858, her husband Robert had died two years earlier, and Clara was on tour in the Netherlands to make money to support her family. Brahms came to her home in Düsseldorf, in part to help watch her children. He wrote to her during her tour:

My beloved friend,

Night has come on again, and it is already late, but I can do nothing but think of you and am constantly looking at your dear letter and portrait. What have you done to me? Can’t you remove the spell you have cast over me? …

How are you? I did not want to ask you to write, but do so long for letters from you. Besides, I know only too well how you are – you are holding your head up. So just write me a word or two occasionally, and I shall be happy – just a friendly greeting to say that you are keeping well and that you will be back in 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2 days!…

Do cheer me with writing me a few lines. I want them so badly, but above all, I want you.

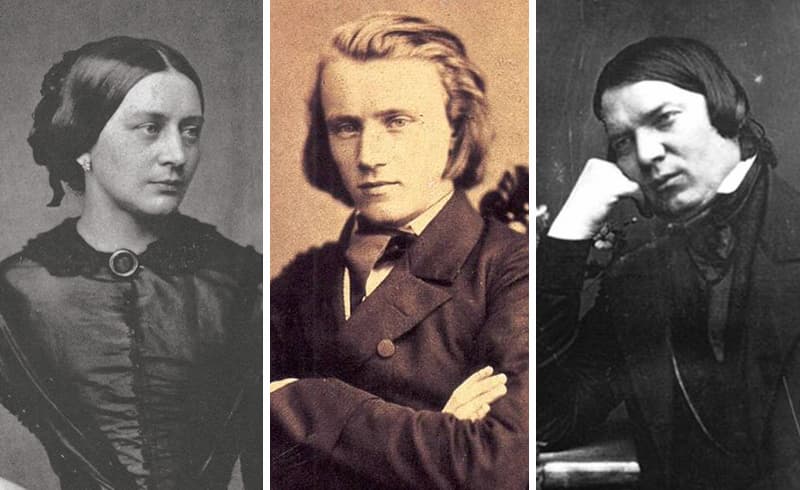

Brahms and the Schumanns

Learn more about the friendship and love triangle between Robert, Clara, and Johannes.

Richard Wagner, 1863

Richard Wagner and Cosima Wagner

Richard Wagner and Cosima Wagner’s marriage became one of the most influential in music history. However, the relationship had an inauspicious start. Richard wrote this letter to his mistress Maria Volkl shortly after first declaring his love to Cosima (!):

Now, my darling, prepare the house for my return, so that I can relax there in comfort, as I very much long to do… And plenty of perfume: buy the best bottles, so that it smells really sweet. Heavens! How I’m looking forward to relaxing with you again at last. (I hope the pink drawers are ready, too???) – Yes, indeed! Just be nice and gentle, I deserve to be well looked after for a change.

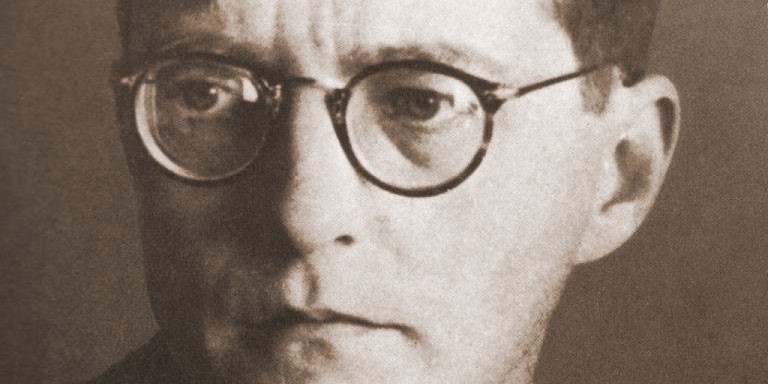

Gustav Mahler

During their engagement, Gustav Mahler wrote this letter to his fiancée Alma, to let her know she must decide between becoming his wife or pursuing her passion for composing music.

Almschi, I beg you, read this letter carefully. Our relationship must not degenerate into a mere flirt. Before we speak again, we must have clarified everything, you must know what I demand and expect of you, and what I can give in return – what you must be for me. You must “renounce” (your word) everything superficial and conventional, all vanity and outward show (concerning your individuality and your work) – you must surrender yourself to me unconditionally… in return you must wish for nothing except my love! And what that is, Alma, I cannot tell you – I have already spoken too much about it. But let me tell you just this: for someone I love the way I would love you if you were to become my wife, I can forfeit all my life and all my happiness.

Learn more about the beautiful Alma Schindler’s background, her marriage to Gustav, and why he wrote this letter.

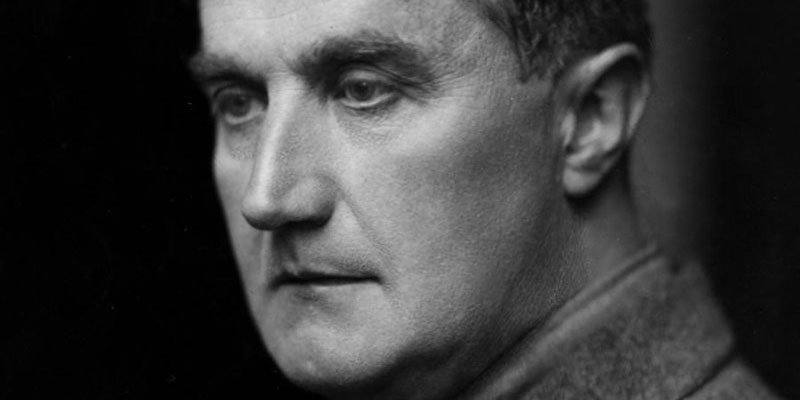

Jean Sibelius, 1891

Sibelius wrote this letter to his fiancée Aino in early January 1891:

My own Aino darling,

Thank you for your letter and your Christmas cards. Your relatives have all been very kind to me. Please give them my respects and thank them most warmly, won’t you. But it is you who loves me more than anyone else has done, and I want you to be sure that I love you and belong to you with all my heart. Every time you write to me, I discover some new aspect of your personality. It makes me feel as if you are a store of treasures to which only I have the key, and you can imagine how proud I am to own it. You are so natural and sincere, which I like. When in the future we have a home of our own and are together alone, we must never be anything other than wholly ourselves, natural, tender towards each other, and devoted. I think and hope that you will be content with me in this respect. It is perhaps unmanly to say so, but you know, Aino, that I have always wanted to be caressed and have always missed its absence. At home, I was the only one who was demonstrative, and this in spite of the fact that I was basically very shy. But up to now, only you have caressed me, and perhaps you have thought it tiresome of me to ask you often to do this, my darling. This could well have remained unwritten, but as I am writing as quickly as I am thinking (hence my superb handwriting!), and this came into my head, it can just as well go into the letter. I sometimes cannot believe that a person like you loves me, for you are a wonderful woman.

Aino and Jean Sibelius

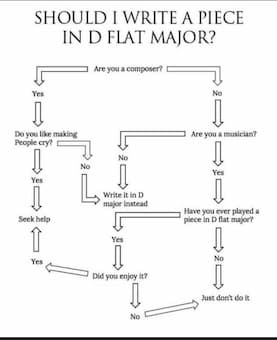

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”