Today, we’re looking at seven of Mozart’s saddest pieces of music, ranking them in a totally subjective list, from least sad to most sad.

So join us as we listen to various symphonies, sonatas, and more, and learn a bit about the stories behind each piece.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1789

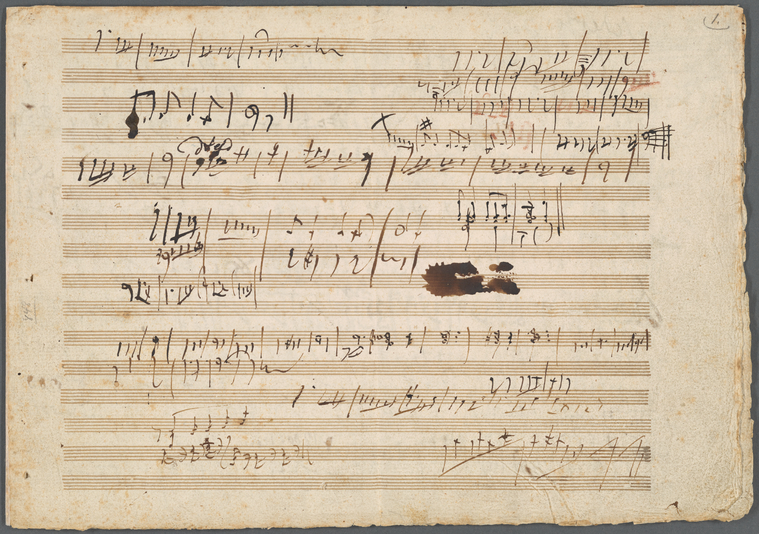

By 1788, a mature Mozart had begun keeping meticulously detailed records of his output. Based on his records, we know that he finished this symphony after a matter of weeks on 25 July 1788.

Although the Fortieth has a reputation for being a tragic symphony, its origins weren’t particularly dramatic: indeed, it was probably written for a concert series at a casino.

Various historians have claimed that Mozart never got to hear the work performed, but later scholarship has disproven this legend. How? Because he rewrote the woodwind parts, suggesting that he’d heard them played…or, at the very least, was revising and anticipating an imminent performance.

Although this symphony could be thought of as sad, better words to describe it might be worried, agitated, or turbulent. Mozart’s most overtly sorrowful compositions appear later on this list, which is why this one doesn’t rank higher.

Mozart turned seventeen years old in 1773. Amazingly, he had already written twenty-four symphonies, and that October, he wrote his twenty-fifth. (By the way, legend has it that he wrote it within two days of finishing his previous symphony!)

Mozart’s 25th Symphony draws from the Sturm und Drang (“storm and stress”) movement, which was popular in European music at the time. Music in the Sturm und Drang style valued extreme emotions and subjectivity, traits that pushed back against Enlightenment Era priorities like rationalism and detached objectivity.

Mozart embodied the values of the Sturm und Drang style by writing in a minor key and employing rhythmic syncopations.

Like his other G-minor symphony above, the emotional tone here is more furious than sad.

In the summer of 1778, when Mozart was twenty-two, he and his beloved mother, Anna Maria, were living in Paris. His father, who usually oversaw his prodigy son’s travel and career, was unable to leave Salzburg, so he sent his wife off to accompany Wolfgang instead while he micromanaged what he could via letter.

Wolfgang obeyed orders, taking on a few students, composing, and networking. In June, his mother wrote letters home complaining of tiredness and a sore throat. We don’t know for sure, but it seems likely she didn’t want to pay to see a doctor, as her husband was always complaining about money.

Anna Maria Mozart

Unfortunately, whether or not she realized it, her life was in danger, and her health deteriorated quickly. On June 30th, last rites were administered, and on July 3rd, she died. It is still uncertain what she died of, although it’s widely believed to be typhoid fever.

Panicked, Mozart prepared his father by lying to him in a letter, claiming that she was only sick, not dead. When he finally admitted the truth, his father blamed him for what had happened.

It’s not known for sure when Mozart wrote this violin sonata in 1778, but many listeners believe that it was inspired by his feelings surrounding his mother’s sudden shocking death and his father’s hurtful reaction. It is melancholy with tinges of dramatic bitterness.

We don’t know exactly when Mozart wrote his twelfth piano sonata. He could have written it during visits to Munich or Vienna, or, most intriguingly, during a visit to his hometown of Salzburg, during which he introduced his new wife Constanze to his father…no doubt a nerve-wracking and emotional trip!

Regardless of the sonata’s origins, its second movement is deeply emotional. The opening theme is not particularly sad (it’s more wistful than anything), but as it develops, it grows more and more quietly despairing, traversing between sunlight and shadow in a deeply affecting way.

Mozart wrote his twenty-third piano concerto two months before the premiere of The Marriage of Figaro, and opera was clearly on his mind. You can hear it in the tragic aria-like melody that he gives to the solo piano.

Interestingly, this is the only piece of music that Mozart ever wrote in F-sharp minor.

It’s interesting to remember when hearing modern performances that Mozart likely improvised details while playing the solo piano part and that this tradition of improvisation has been largely discarded.

Mozart was twenty-six years old when he wrote his Fantasia in D-minor for solo piano. It’s a short piece: just a hundred measures, split into a few parts and hovering around six minutes. Its unexpected, unpredictable form helps contribute to the feeling of listlessness and sadness.

We don’t know why Mozart wrote this work. We do know that he didn’t actually finish it himself, as it was unfinished upon his death in 1791.

The final ten measures were likely composed by German composer August Eberhard Müller, although others like Mitsuko Uchida have stepped forward with their own endings.

Mozart’s Requiem contains his saddest music, both for the content of the music and for the tragic story behind its composition.

In 1791, a wealthy count named Franz von Walsegg commissioned Mozart to write a Requiem in honour of his recently deceased wife. (The count also was an amateur musician who, alarmingly, wanted a work to pass off as his own.)

Tragically, Mozart died before the Requiem could be finished. He was only thirty-five years old, and to this day, we don’t know exactly what killed him.

His widow was left with two children to raise. Mozart hadn’t left enough money for her to live on, and she knew that to secure her family’s economic security, she would have to hire a composer to finish the Requiem so that she could collect the commission fee.

Franz Xaver Süssmayr, a composer and Mozart student, took on the monumental task of finishing this masterpiece. We do not know exactly what Süssmayr contributed to the Requiem, but he later claimed he wrote the Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei, which appear toward the end.

The saddest movement of the Requiem is likely the Lacrymosa (“Weeping”), which combines sorrow and splendour in equal measure.

Between the tragic subject matter and the knowledge that it turned out to be his farewell to music, it’s our pick for the saddest music that Mozart ever wrote.

Which work do you think is Mozart’s saddest? Would you re-order our list? Let us know in the comments!

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.