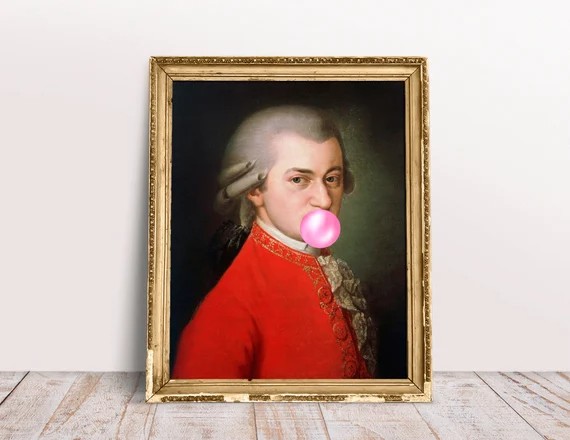

Mozart’s music doesn’t stand politely in the corner, but it nudges you in the ribs, rolls its eyes, and occasionally trips over its own feet on purpose.

What makes Mozart remarkable is not just that he was brilliant, but that he is very funny. And not accidentally funny, or funny because you know a lot of music, but genuinely and immediately funny in the way human beings recognise across centuries.

As we celebrate Mozart’s 270th birthday on 27 January 2026, it becomes clear that his humour still works because it is rooted in human behaviour. Things like vanity, impatience, swagger, awkwardness, and the joy of seeing someone slightly overdo things.

The Oldest Joke in the Book

Many Mozart jokes work on surprise, basically the same mechanism as a good punchline. You think you know where something is going, and then it doesn’t go there at all. Take the “Overture” to The Marriage of Figaro.

It hurtles forward at breakneck speed, bubbling with excitement, as if everyone is late and lying about it. There is no grand introduction, no dignified scene-setting. The music bursts in mid-thought, like someone already halfway through a conversation.

It’s funny because it feels completely uncontrolled and is barely containing its own energy. It’s perfect for setting up an opera where plans unravel almost immediately.

Mockery with a Smile

If Mozart had lived today, he might have loved parody videos. His A Musical Joke K. 522 is exactly that. It’s a straight-faced spoof of bad composers and overconfident amateur performers.

The brilliance of the piece lies in how sincerely it pretends to be respectable. Nothing is signposted as a joke. The music smiles politely and behaves itself, at least at first. The opening sounds harmless enough, but soon, tiny cracks begin to show.

Harmonies arrive where they clearly shouldn’t, and melodies wander off mid-thought, distracted by something more interesting. Instruments appear not to be listening to one another, each cheerfully pursuing its own idea while the others carry on regardless.

By the end, the whole thing unravels into a glorious mess. Everyone tries to finish together and fails spectacularly. What makes the piece genuinely funny is Mozart’s restraint. He doesn’t push the joke too far or turn it into a caricature. Mozart knows exactly how close he has to stay to reality.

When Seduction Becomes a Spreadsheet

Mozart’s operas are funny because the music refuses to keep secrets. Characters may try to present themselves as noble, innocent, or in control, but the orchestra has other ideas. It whispers, comments, contradicts, and occasionally bursts out laughing.

The result is comic timing of the highest order as people expose themselves not through what they say, but through what the music reveals behind their backs. Nowhere is this clearer than in Don Giovanni, and especially in Leporello’s famous “Catalogue Aria.” On paper, it is a list, but in practice, it becomes one of the most devastating comic portraits in opera.

The tune bounces along with brisk, almost businesslike cheer, as if Leporello were reading out the contents of a ledger or ticking items off a grocery list. The music is jaunty, efficient, and oddly proud of its own organisation. Meanwhile, the content grows more and more outrageous. Seductions blur into compulsions, and charm slides into predation.

The audience is left laughing slightly uncomfortably at the sheer absurdity of treating moral catastrophe as clerical work. That mismatch is the joke. The music sounds far too pleased with itself. Don Giovanni is never defended, never excused, and never directly condemned; he is simply reduced to a spreadsheet.

Sighs, Schemes, and Smirks

In Così fan tutte, the trio “Soave sia il vento” sounds tender, heartfelt, and almost heartbreakingly sincere. And yet, if you know the story, the audience is in on the joke. Every note of beauty is delivered while the characters are actively deceiving each other, pretending to be someone they are not, and scheming with near-perfect dramatic obliviousness.

The humour here is both cruel and gentle. It’s cruel because the characters’ emotions are on display while they are lying, flirting, and swapping identities in ways that would make any bystander raise an eyebrow.

It’s gentle because Mozart never mocks them harshly but simply allows the gap between intention and reality to become laughably obvious. Think of it as the operatic equivalent of someone sending a perfectly earnest text while their friends know they’re setting up a prank.

The music is flawless and serious, while the characters are recognisably human, full of vanity, desire, and clueless overconfidence. It is a masterclass in operatic comedy. It is heartbreakingly beautiful, meticulously tender, and yet utterly aware of how ridiculous human behaviour can be.

The Art of Instant Distraction

Rolando Villazón as Papageno in Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Metropolitan Opera © Evan Zimmerman / Met Opera

And then there is “Papageno” in The Magic Flute, one of Mozart’s most delightful comic creations. Papageno’s charm lies not in heroism or sophistication but in his stubborn ordinariness. He whistles, he sulks, he panics, and he makes mistakes that are at once ridiculous and utterly relatable.

One of the best examples is his aria “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” in which Papageno fantasises about finding a partner. The melody is simple, almost plodding, bouncing along like a man trying to march confidently while tripping over his own feet.

He repeats the same ideas with childlike insistence, each iteration more desperate and endearing than the last. And then comes the aria’s comic peak. Papageno, in a moment of theatrical despair, threatens suicide only to be instantly distracted by the sound of bells signalling food or the promise of a wife.

Mozart perfectly times the orchestra to underline the absurdity. Papageno’s despair evaporates in a beat, replaced by delight, leaving the audience laughing at his quick flip-flop between panic and pleasure. Papageno is a reminder that life is absurd, chaotic, and sometimes wonderfully silly.

Not-So-Final Farewells

One of Mozart’s favourite comic tricks is the fake ending. It’s the musical equivalent of saying goodbye three times, waving, and then standing in the doorway like he forgot something important.

It’s a subtle kind of mischief as the music seems to promise closure, only to pull the rug out from under the listener’s expectations. Take the final movement of the “Jupiter Symphony.” Just when you are leaning back, convinced the piece has triumphantly concluded, Mozart nudges the orchestra forward for one more cheeky flourish.

The effect is delightful as the listener is caught between surprise and admiration, laughing along with the composer’s playful audacity. This is comic timing in its purest, non-verbal form. The music is alive, aware of its audience, and utterly confident in its ability to provoke a smile.

Mozart’s genius was never just in the notes he wrote, but in the way he invited us to laugh at life itself. Mozart understood the absurd, unpredictable, and wonderfully human side of existence. Two hundred and seventy years on, his music still grins, nudges, and winks, reminding us that brilliance and humour should live happily together.