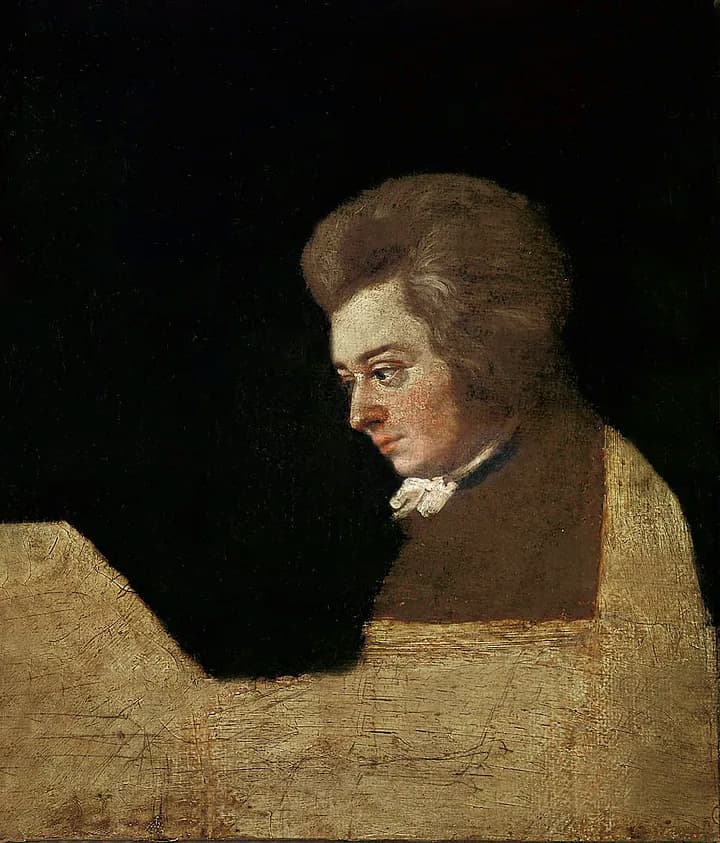

Joseph Lange: Mozart at the keyboard (unfinished), 1789 (Mozart-Museum, Mozarts Geburtshaus)

Mozart essentially created a unique conception of the piano concerto as he was looking to solve the problem of how the thematic material is to be divided between the piano and the orchestra. In these later works, Mozart “strives to maintain an ideal balance between a symphony with occasional piano solos and a virtuoso piano fantasia with orchestral accompaniment.” Mozart’s solutions are non-formulaic as each concerto, although unmistakably resembling its siblings, is a thoroughly individual response.

The Viennese piano concertos are probably the most personal works Mozart ever conceived, as they were composed for his own public performances. As we commemorate Mozart’s death on 5 December, let us explore some of these most important works of their kind.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart sent his father the list of subscribers who paid an entrance fee of six gulden for three concerts at the Trattnerhof on 20 March 1784. “Here you have the list of all my subscribers,” he writes, “I have 30 subscribers more than Richter and Fischer combined. The first concert on March 17th went off very well. The hall was full to overflowing, and the new concerto I played won extraordinary applause. Everywhere I go, I hear praises of that concerto.”

The concerto in question was Mozart’s K. 449, and Mozart had gotten involved in subscription concerts via his colleague Franz Xaver Richter. Richter had rented a hall for six Saturday concerts, and the nobility subscribed. However, as Mozart writes, “they really did not want to attend unless I played. So Richter asked me to play. I promised him to play three times and then arranged three subscription concerts for myself, to which they all subscribed.”

Mozart suggested that K. 449 “is one of a quite peculiar kind,” and he called it a happy medium between what is too easy and too difficult. In fact, K. 499 is rather intimate chamber music with the “Allegro Vivace” exploring the tensions between the major and minor tonalities. An exquisitely expressive “Andantino” gives way to a dazzling rondo featuring much contrapuntal wizardry.

The Piano Concerto No. 17, K. 453 is one of only two by Mozart to have been written for a player other than himself. In fact, it was written for his student Barbara Ployer, daughter of Gottfried Ignaz von Ployer, a Viennese emissary to the Salzburg court. Ployer was a fine pianist and she soon became one of Mozart’s favourite students. He also provided her with counterpoint instructions, and he asked her to come up with musical ideas of her own. Leopold Mozart was not impressed and wrote, “You want her to have ideas of her own—do you think everyone has your genius?”

Mozart monument in Vienna

The orchestration of this concerto is notable for the independence Mozart provided to the woodwinds. Clearly, Mozart could rely on a much higher standard of the orchestral winds than he had experienced in Salzburg. The prominence of the winds is dramatically demonstrated in the second movement, which opens with a serene theme in the strings that comes to a dramatic and operatic stop. This is followed by an extended episode in which the strings play backup for the solo flute, oboe, and bassoon.

The opening movement unfolds in a relaxed and almost casually expressive mood. One gorgeous melody seems to chase the next, and the contrasting theme ventures into unexpected tonal areas. Instead of the expected rondo, the finale presents five variations on a simple tune but then pauses and seemingly jumps into an entirely new movement. Barbara Ployer played the premiere in June 1784.

Mozart benefited artistically and financially from his subscription concerts. And he certainly enjoyed his time as the darling of the Viennese concert scene. The Piano Concerto No. 19 premiered in the spring of 1785, possibly one of the busiest periods of Mozart’s life as a performer. Leopold came for a ten-week visit and was struck by the level of activity. “Every day, there are concerts, and the whole time is given up to teaching, music, composing and so forth. Since my arrival, your brother’s fortepiano has been taken at least a dozen times to the theatre or some other house.”

As Alfred Brendel writes, “the first movement of K. 459 is remarkable; no other movement in the whole series of twenty-three piano concertos evinces such subordination on the part of the piano to the orchestra: purely solo passages are rare, and for much of time the solo instrument is occupied in providing an accompaniment to various sections of the orchestra, notably the woodwinds.” That opening movement, unusually, also relies entirely on one theme, a march-like melody that dominates proceedings.

The slow movement forgoes a development section and sounds like a close collaboration among the soloist, the strings and the winds. That dialogue between the instrumental forces culminates in a final coda. The sonata-rondo finale seems a fitting conclusion as it playfully takes us into the world of opera buffa.

Mozart entered the Piano Concerto in D Minor, K. 466, in his new catalogue of compositions on 10th February 1785. It is the first of his piano concertos in the minor key. To be sure, the minor tonality adds a new dimension of high seriousness to the form, a mood immediately heard in the dramatic orchestral opening. The concerto is scored for trumpets and drums, as well as the now usual flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons and horns, with strings, and the violas divided.

Leopold Mozart was present at the premiere, and he wrote to his daughter, “We drove to Wolfgang’s first subscription concerto, at which a great many members of the aristocracy were present… Then we had a new and very fine concerto by Wolfgang, which the copyist was still copying when we arrived, and the rondo of which your brother did not even have time to play through as he had to supervise the copying.” Isn’t it amazing that in about three weeks, Mozart was able to write the most perfect and most passionate of concertos?

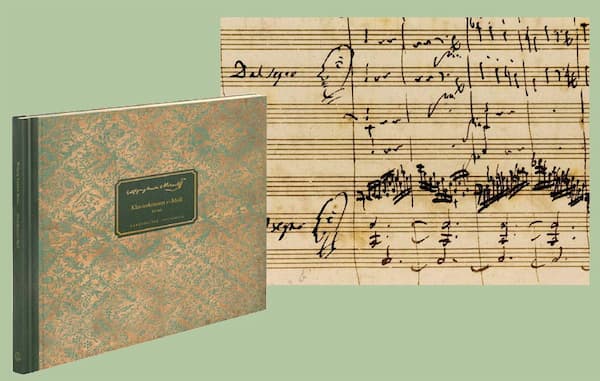

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 autograph score

The D-minor concerto was a turning point as it was Mozart’s first “symphonic” concerto. The orchestra is given a completely equal position, and the wind parts become even more weighty. The sense of drama is evident in the large-scale orchestral introduction, and many of the piano parts would comfortably fit into an operatic seria. However, they are much more than just a beautiful melody. A noted performer writes, “Mozart probably found in D minor the threatening and demonic colouring he was looking for. A very personal statement!”

Mozart completed his 21st Piano Concerto in C Major, K. 467, on 9 March 1785, exactly a month after the premiere of his first concerto in the minor key. Contrary to the dramatic narrative of K. 466, the C-Major Concerto is a work filled with humour that focuses on elegant simplicity. A critic reported that Mozart’s playing “captivated every listener and established Mozart as the greatest keyboard player of his day.” Leopold Mozart added that the work was “astonishingly difficult,” and it would be the last time that father and son would actually see each other.

Presently, this concerto is known as the Elvira Madigan Concerto because the use of the second movement contributed strongly to the mood of the film of that name. The work opens quietly, with unison strings setting an opera buffa stage. There is an air of anticipation as the winds once again play an important role. They initiate little fanfare, double the strings, or even capture centre stage with melodic interjections. The soloist enters with new and independent ideas and then follows its own path.

Soloist and orchestra have a unique relationship here as both forces seem primarily concerned with their own material. As Donald Francis Tovey writes, “In no other concerto does Mozart carry so far the separation between the two… Mozart has succeeded in making the piano as capable a vehicle of his thought as the orchestra.” The dream-like and elegant second movement provides for a nocturnal atmosphere, while the concluding “Rondo” returns us to the opening mood. Mozart borrowed a theme from his concerto for Two Pianos, K. 365, and the entire movement is based on that witty tune with plenty of scope for soloists and the orchestra to show their brilliance.

Mozart completed his Piano Concerto in A Major, K. 488, on 2 March 1786. It was designed for use in a series of three subscription concerts that Mozart had arranged for part of the winter season. Simultaneously, Mozart was busy working on his first Italian opera for Vienna, Le nozze di Figaro. Yet, times had changed. Only three years earlier, the Viennese public had lavishly acclaimed the piano concertos by the young virtuoso; now, they sought musical entertainment elsewhere.

The concerts were not well subscribed, but Mozart nevertheless went ahead “believing that he could seduce the public with his unquenchable ability to come up with something new and tantalising.” K. 488 has remained popular and frequently performed as it creates a sense of weightlessness. And the role of the piano becomes even more versatile. It functions as a solo instrument and accompanies the orchestra, but it also integrates into the orchestra. In a sense, it functions as an orchestral instrument.

In his orchestration, Mozart replaced the bright-toned oboes with clarinets, providing a much darker colouration. This is particularly evident in the passionate and richly chromatic slow movement in the unusual key of F-sharp minor. However, the orchestration remains essentially intimate, as Mozart foregoes trumpets and drums. The chamber-music feeling of the first two movements is reinforced by active interchanges between the woodwinds. The soloist initiates an extensive rondo finale that has the character of a fast stretta, all ending in a buffo-like coda.

The second piano concerto in the minor key, the Concerto in C-minor, K. 491, was completed on 14 March 1786. It is scored for clarinets and oboes, flutes, pairs of bassoons, horns, trumpets and drums, and strings. It opens with an ominous theme that Beethoven would subsequently use as the inspiration for his C-minor Piano Concerto. A sense of foreboding permeates the entire movement, disturbed only momentarily by the tranquillity of the second theme.

Piano Concerto C minor K. 491 by W. A. Mozart

The ”Larghetto” movement opens in the major key, and episodes are framed by the principle melody. However, the music is soon led into the minor key by the woodwind, and a ray of serenity returns us to the opening. Mozart concludes this masterwork with a set of variations.

Piano Concerto No. 27 in B-flat Major, K. 595

Mozart completed the cycle of twelve Viennese concertos in December 1786. He waited almost 14 months to write another piano concerto, the so-called “Coronation.” Another three years passed before he brought this grand series to a close with the B-flat Major Concerto, K. 595. To scholars, this “work stands along, not only in terms of its chronological separation from the other piano concertos but because its content and character make it unique.” It is probably the most deeply personal of all Mozart concertos.

The clearly defined drama of the minor key concertos is replaced by what has been described as “a more personal notably resigned accent” and a feeling of “subdued gravity.” Mozart gave the premiere on 4 March 1791, and it was the last such appearance before the Viennese public. Alfred Einstein wrote, “it was not in the Requiem that Mozart said his last word… but in this work, which belongs to a species in which he also said his greatest.”