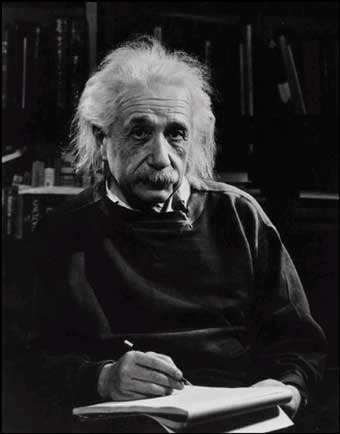

Camille Saint-Saëns in 1900

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) was one of the leaders of the French musical renaissance during the later part of the 19th century. He was a scholar of music history and tolerant of a wide range of musical issues and directions. He tellingly wrote: “I am an eclectic spirit. It may be a great defect, but I cannot change it; one cannot make over one’s personality.” His views on expression and passion in art conflicted with a prevailing Romantic aesthetic that was engulfed by Wagnerian influences.

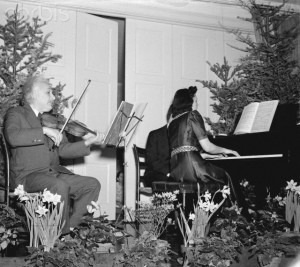

Camille Saint-Saëns, 1846

In his memoirs he wrote, “Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotion, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art. He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.” Saint-Saëns possessed a mastery of compositional technique, and his ease, ingenuity, naturalness and productivity was compared to “a tree producing leaves.” Yet, during a period of extreme musical experimentations, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and by the time of his death on 16 December 1921, his compositional style was considered deliberately old fashioned. Scathing critical opinion suggested “Saint-Saëns has written more rubbish than any one I can think of. It is the worst, most rubbishy kind of rubbish.”

Saint Merri Church in Paris

Saint-Saëns was born in the Rue du Jardinet in the 6th arrondissement of Paris on 9 October 1835. Two months after the christening, his father died of consumption and young Camille was taken to the country. “It is not generally realized,” a music critic wrote, “that Saint-Saëns was the most remarkable child prodigy in history, and that includes Mozart.” He produced his first composition at age 3, and publically performed a Beethoven violin sonata at age 4. Saint-Saëns made his official public debut at the Salle Pleyel at the age of ten, performing piano concertos by Mozart and Beethoven. An anecdote tells that he offered to play as an encore any of Beethoven’s 32 piano sonatas from memory. Hector Berlioz admiringly wrote, “This young man knows everything, and he is an absolutely shattering master pianist,” with Franz Liszt declared him “the world’s greatest organist.” In addition to his musical prowess, Saint-Saëns excelled in his academic studies. He distinguished himself in the study of French literature, Latin, Greek, and Divinity. He acquired a taste for mathematics and the natural sciences, including archaeology, astronomy and philosophy. At the age of thirteen, Saint-Saëns was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire where he specialized in organ studies and took formal courses in composition.

The old Conservatoire de Paris, early 19th century

Saint-Saëns competed for the Prix de Rome in 1852, but the award went to Léonce Cohen instead. Upon graduation from the Conservatoire, Saint-Saëns accepted the organist post at Saint-Merri, and by 1858 he was appointed organist of La Madeleine, the official church of the Empire. Saint-Saëns became a teacher at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse and he counted Fauré, Messager and Gigout among his most prominent students. Although he supported and promoted the music of Liszt, Schumann, and Wagner, Saint-Saëns wrote, “I admire deeply the works of Richard Wagner in spite of their bizarre character. They are superior and powerful, and that is sufficient for me. But I am not, I have never been, and I shall never be of the Wagnerian religion.” Going against the grain of French musical life in the mid-19th century, his main love was instrumental music. Extraordinarily active in the field of chamber music, not only as a composer but also as a performer, he might rightfully be considered one of the pioneers of French chamber music. Saint-Saëns left his teaching position in 1865 and pursued a career as a performer and composer.

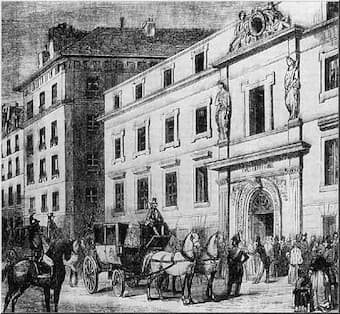

Saint-Saëns at the piano for his planned farewell concert in 1913,

conducted by Pierre Monteux

Saint-Saëns was an excellent craftsman with a fine sense of musical style, and he placed his talents into the services of the Société Nationale de Musique. He wrote important articles in support of performing music by living French composers, and embarked on a number of operatic projects. His opera Le timbre d’argent had its première at the Théâtre Lyrique in 1877, and he scored a solid success with Samson et Dalila, a work that kept a foothold on the international stage. Saint-Saëns was elected to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1881, and he was made an officier of the Légion d’Honneur in 1884. Always a keen traveler, Saint-Saëns made 179 trips to 27 countries between 1870 and the end of his life. Avoiding Parisian winter, Saint-Saëns spent substantial portions of the year in Algiers and various places in Egypt. He resigned from the Société Nationale in 1886, and although his popularity in France began to wane, he was still regarded as the greatest living French composer in America and England.

Interior of Saint-Saëns’ tomb in Montparnasse

Saint-Saëns performed his last concert on 6 August 1921, and concluded his conducting career shortly thereafter. He died of a heart attack on 16 December 1921 in Algiers, and his body was taken back to Paris for a state funeral at the Madeleine. During a period immersed in modernism of all kinds, Saint-Saëns remained stubbornly traditional, and his steadfast dedication to musical moderation, clarity, balance and precision deservedly earned him the nickname “French Beethoven.” Contemporary critics, on the other hand, polemically called him “the greatest composer without talent.” From the perspective of music history, however, we now understand that Saint-Saëns compositional approach, deeply inspired by French classicism, was an important forerunner of the neoclassicism practices of Ravel and others.