Auguste and Louis Lumière

I am just an ordinary city girl, and one of the greatest joys during the burning hot day of summer is a visit to my local cinema. Sitting in a comfy chair in a chilled air-conditioned room with a huge bag of popcorn in my hand while I look at a giant screen and listen to beautiful music on surround sound is one of my greatest joys. I certainly prefer it to looking at my computer or TV screen at home, with my mother or siblings interrupting me all the time. So I decided to write a little blog on the greatest composers of film music, and I’ll start with a bit of trivia.

Cinématographe

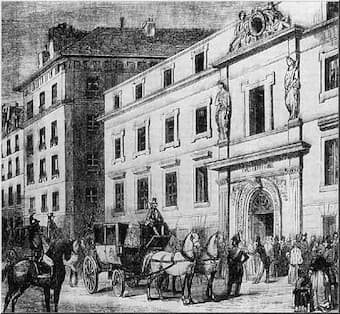

Do you know what extraordinary event took place in Paris on 28 December 1895? I give you a little hint by telling you that it involved the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière. Maybe you know that the Lumière brothers were manufacturers of photography equipment, best known for their Cinématographe motion picture system. On that specific day in 1895, in what is considered the birth of cinema, they showed a series of short films to a Parisian audience. Even more remarkable is the fact that a pianist improvising on popular tunes accompanied this first screening.

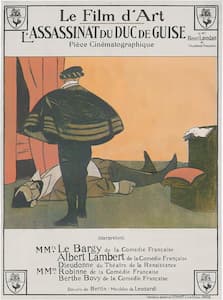

L’Assassinat du duc de Guise

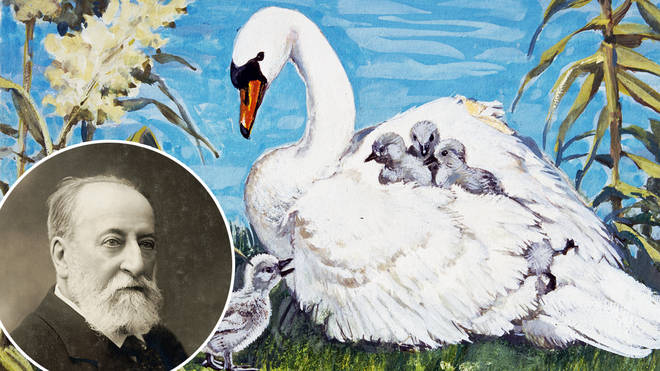

It seems a bit funny, but the so-called silent film era wasn’t silent at all, but included music to establish a mood. As literally thousands of movie theaters sprang up in Europe and the United States, the solo piano was the most common instrument for musical accompaniment. “In a number of theaters, a percussionist was added to create special effects, and soon special theatre organs were built to produce a wide range of musical colors and effects, including gunshots, animal noises, and traffic sounds.” Larger theaters were known to feature ensembles, including chamber orchestras and occasional singers. We also know that the music played during screenings generally fell into three different types; borrowings from Classical music, arrangements of well-known popular, patriotic, or religious tunes, and newly composed music. Here then is the second trivia for today. Do you know who is generally credited with composing the first original film score? The answer is Camille Saint-Saëns, who wrote original music for the film “L’Assassinat du duc de Guise” (The Assassination of the Duke of Guise) in 1908.

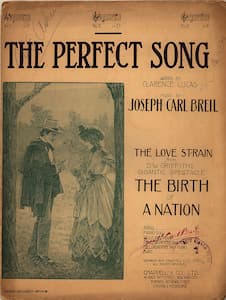

Sheet music of “The Perfect Song” from

The Birth of a Nation

For our next trivia question we turn to the United States and “the most controversial film ever made in the United States,” also called “the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history.” The silent film in question was called “The Birth of a Nation” and featured a plot, part fiction and part history, that chronicles the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the relationship of two families in the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. While Abraham Lincoln is portrayed positively, as a friend of the South, the film “has been denounced for its racist depiction of African American. The film portrays them, many of whom are played by white actors in blackface, as unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women. The Ku Klux Klan is portrayed as a heroic force, necessary to preserve American values, protect white women, and maintain white supremacy.”

Joseph Carl Breil in 1918

It’s all pretty horrible and makes me cringe, and some critics say that it “caused an entire century of racism.” However, the reason I decided to feature this particular film in this blog has nothing to do with the subject. Rather, it seems that the director D.W. Griffith “elevated cinema to an art form with this classical Civil War spectacle, and Joseph Carl Breil composed a three-hours-long landmark score that featured music by Richard Wagner, patriotic tunes for the Civil War scenes, “and new music featuring a number of leitmotifs to accompany the appearance of specific characters.” “The Perfect Song” is regarded as the first marketed theme song from a film, with critics calling the score “a mix of Dixieland songs, classical music and vernacular heartland music; an early, pivotal accomplishment in remix culture.”