by

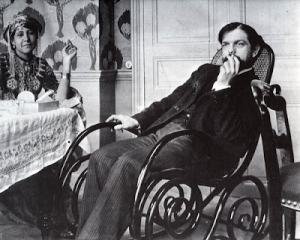

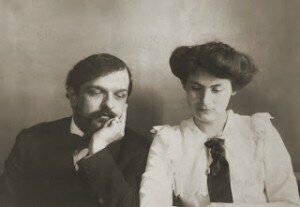

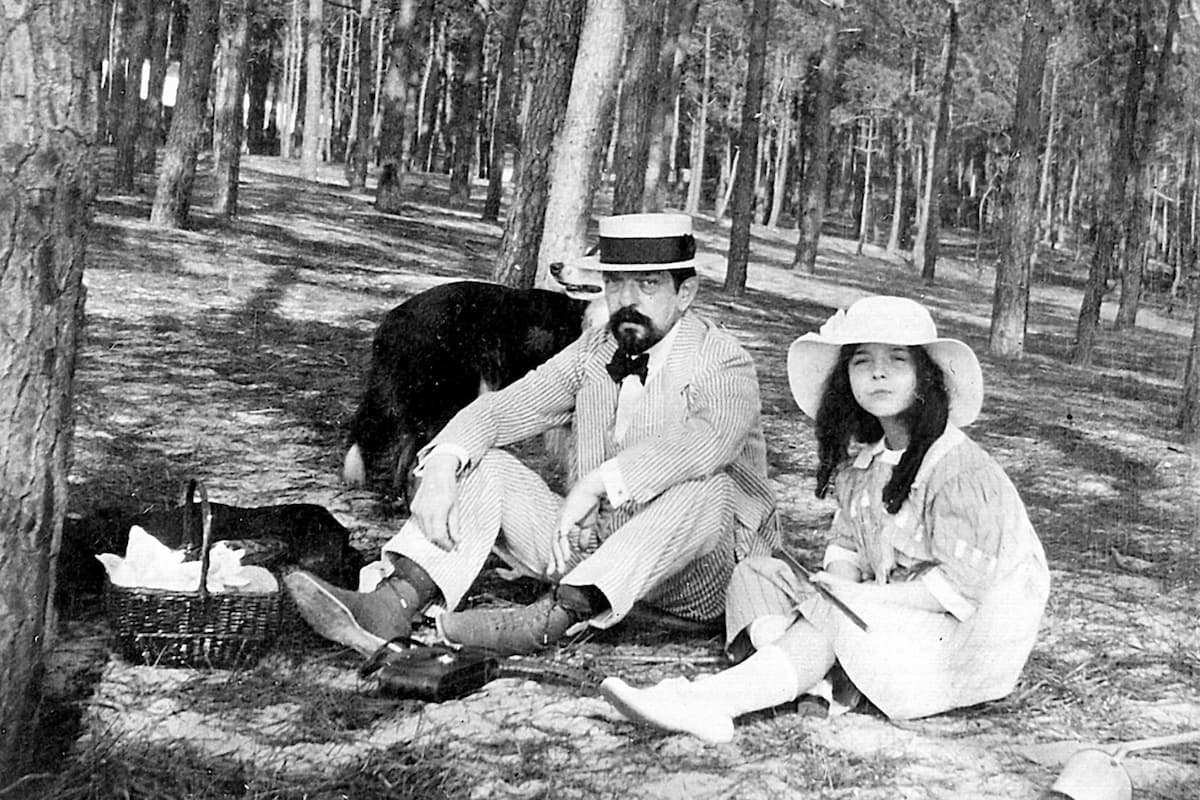

Claude Debussy © Henri Manuel/Getty Images

We think of Debussy as the composer of the dreamworld sound of impressionism. He was an active follower of the symbolist movement, which rejected naturalism, realism, and clear-cut forms in favour of the indefinite and the mysterious. The symbolist poets tried to put music at the centre of their world. Verlaine and Mallarmé worked towards a ‘musicalization’ of poetry.

In his musical language, Debussy always included the extra-musical structural format of poetry. By reversing the relationship between a composer and his poetry, Debussy’s songs were more fluid and adventuresome, in comparison to his instrumental music, which was more restricted by the necessity for fixed keys.

In 1892, he became a poet himself, starting work on his Proses lyriques, a set of four songs to which he wrote the poetry, under the influence of the symbolist poets. He completed the set in 1893. At the same time, he had just finished Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1891-4), the String Quartet (1894), and had started work Pelléas et Mélisande (started 1893, completed 1902).

The title, Proses lyriques, is indicative of the problem that French poets faced. French poetry operated under a set of ‘rules and conventions’ that meant that, read as poetry, the verse would have one set of metrical stresses that would be different when read in an ordinary voice. Composers, faced with this difficulty, that would have been fundamental to their text setting, started to look towards prose for inspiration. We note that Debussy’s major opera, Pelléas et Mélisande, sets a prose text.

Debussy’s abandonment of strict verse forms only lasted until 1902. After the premiere of Pelléas et Mélisande, and with only one exception he returned to verse and abandoned prose texts for the rest of his career.

His setting of the Proses lyriques consists of 4 songs: De rêve (1892), De grève (1892), De fleurs (1893), and De soir (1893). He set another 2 songs as the Proses lyriques, set 2, otherwise known as Nuits blanches (1898): Nuit sans fin and Lorque’elle est entrée. In 1915, he set one more piece of his own poetry: Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maisons.

The four poems are full of colour: golden moons, white shivers, gilded leaves (De rêve), white silk, green silk dresses, grey quarrels, white kisses (De grève), green boredom, purple iris, lilies as white jets, black petals of boredom (De fleurs), the blue of my dreams, gold or silver (De soir).

The final song in the set, De soir, is both a commentary on the craziness of a Sunday where everyone heads out to the countryside, the memories of past Sundays, and then finally the night, which comes with velvet steps as the Virgin scatters the flowers of sleep. It’s an extraordinary musing on a weekend day and how it ends.

The 1898 songs, collected under the title of Nuits blanches, are very different in nature: both are tales of disappointed love. The second song, Lorque’elle est entrée (When she first appeared) tells the story of the lover who has fallen out of love and sees his beloved now with different eyes: ‘…deceit was caught in the folds of her skirts; her large eyes glowed with falsehood,’ her sweet words are harsh and wounding in actuality, but nevertheless, when she touches him, he cannot help but feel his desires flare again.

Debussy’s last poem, which he set to music in 1915, is completely different again. It is a Christmas song for a time of war. Noël des enfants qui n’ont plus de maisons (Christmas for children who no longer have houses). It starts with ‘Our houses are gone! The enemy has taken everything, even our beds!’ and leads to the back story of how father went to war, mother has died, and now there are no toys. There’s no daily bread. It closes with: ‘Christmas, listen to us. Our wooden shoes are gone, but grant victory to the children of France!’

No other composers have set these texts – they remain by Debussy for Debussy alone. The problem of French poetry, with its historically strong metres that drove the music, is solved when you move towards prose. Any problems with poets are solved when you’re the poet yourself!