It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, August 3, 2024

Céline Dion - Hymne à l'Amour - Paris Olympic Games (Piano Cover)

Kay Ganda Ng Ating Musika (How Beautiful is Our Music) — University of Mindanao

Prokofiev for Beginners: 10 Pieces to Make You Love Prokofiev

by Emily E. Hogstad

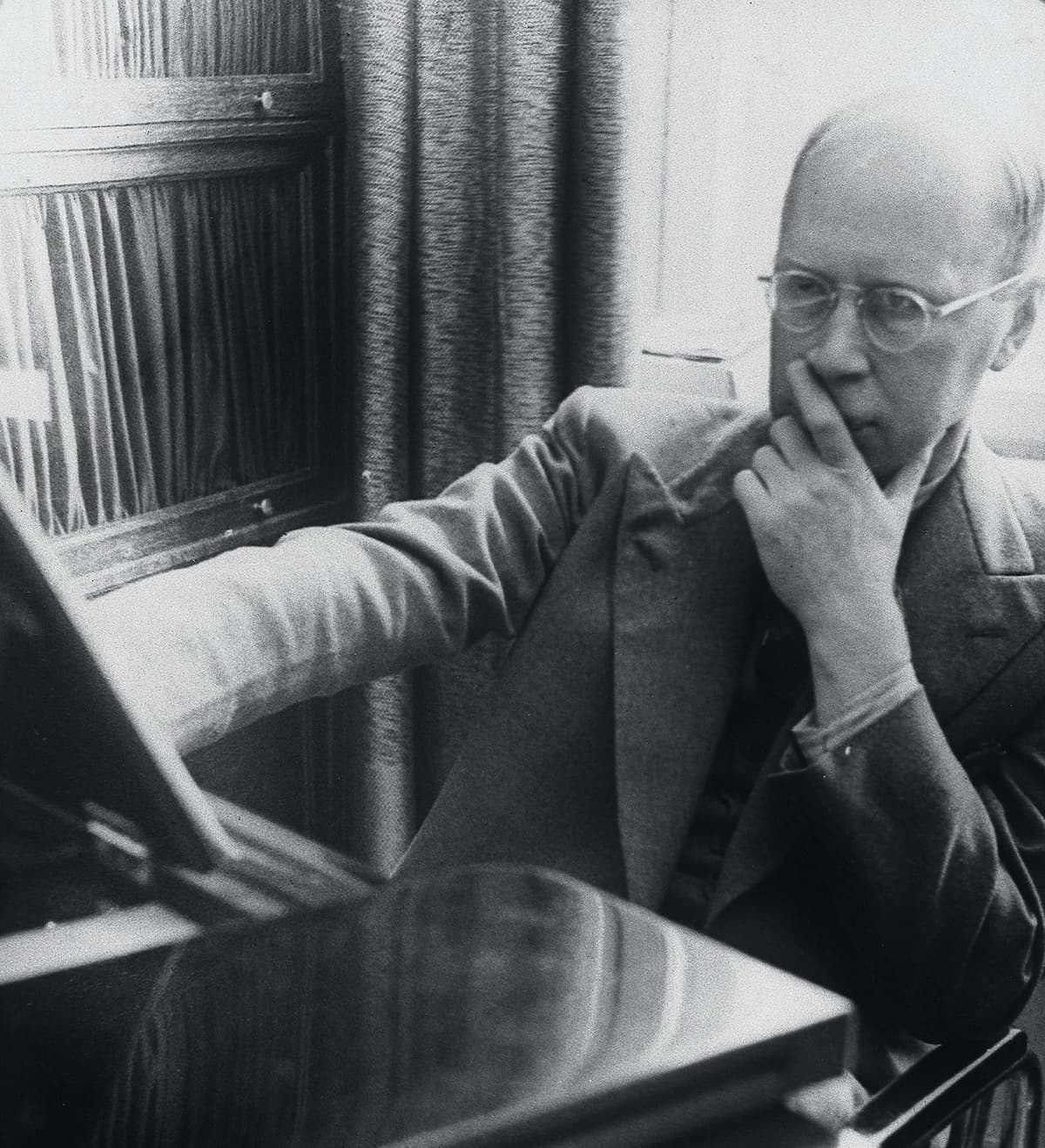

Sergei Prokofiev

Here are a few facts about his life and career:

- Prokofiev’s music blended steely modernism and traditional Russian character. He often combined dissonance and complex rhythms with more melodic and folk-inspired ideas.

- Prokofiev was a child prodigy who began composing at an early age. When he was accepted into the Moscow Conservatory, he was several years younger than his fellow students. (He would irritate his older peers by keeping track of their mistakes.) He cultivated a reputation as a misfit and a rebel.

- Prokofiev had a complicated relationship with Russia and the Soviet Union. He left his homeland in 1918 after the Russian Revolution but, homesick, returned in 1936. He ran into trouble with Soviet bureaucracy, and his ex-wife was even sent to a gulag after attempting to defect.

- In his later years, his health was poor. Prokofiev died on the same day as Joseph Stalin, so his death received relatively little attention.

Intrigued? Hope so! Here are ten works by Sergei Prokofiev to immerse yourself in his word.

Prokofiev began his first piano concerto as a cocky twenty-year-old.

In 1914 he played this concerto at a piano competition. He figured he probably wouldn’t win if he performed a canonical piano concerto, but he might stand a chance if he entered with an impressive performance of his own little-known work. (And yes, he did in fact win.)

This work is fifteen minutes long and in one movement. It’s dramatic, powerful, spiky, and spicy.

In this work, Prokofiev takes a form that was invented in the late sixteenth century – the toccata – and brings it squarely into the mechanized twentieth.

Toccatas have always been fleet and virtuosic, but in his Toccata, Prokofiev brings those adjectives to another level, never allowing the performer (or the audience) a single moment to breathe. It’s a cold-blooded and deeply satisfying work.

Symphony No. 1 in D Classical, Op. 25 (1916–17)

Many composers are terrified to write their first symphony, given the storied history of the genre and the weight of expectations. Brahms, for example, took over twenty years to write and perfect his.

Young Prokofiev, however, turned those expectations on their head when he breezily wrote his brief but enchanting first symphony, nicknamed the “Classical.”

As the name suggests, this symphony is in a neoclassical style that pays tribute to the works of Haydn and Mozart, while putting a modern spin on the genre.

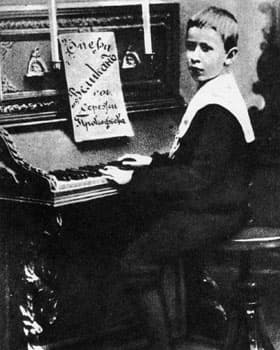

Sergei Prokofiev in 1900

On April 18, 1918, he wrote a typically confident entry in his diary about the premiere: “Rehearsal of the Classical Symphony with the State Orchestra, I conducted it myself, completely improvising, having forgotten the score and never indeed having studied it from a conducting perspective.”

Despite its composer’s devil-may-care attitude, the premiere was a success.

Violin Concerto No. 1 in D, Op. 19 (1916–17)

Prokofiev’s first violin concerto is like the soundtrack to a twisted fairytale, with long lush lines interplaying with repetitive, machine-like virtuosity.

It was composed against the backdrop of the oncoming Revolution. Despite the turmoil in the streets, 1917 turned into the most creatively productive year of Prokofiev’s life.

In 1918, he departed Russia for America, crossing via the Pacific and arriving in California. He made his way across North America, eventually finding himself in Paris, where his violin concerto was belatedly premiered in 1923.

Unfortunately, Parisian audiences in that particular time and place were hoping for something with a little more avant-garde bite, and the fairytale-like first violin concerto wasn’t their cup of tea. But time has been kind to it, and the concerto remains in the repertoire to this day.

Suite from “Lieutenant Kijé”, Op. 60 (1934)

In 1936, Prokofiev returned permanently to his homeland. However, before the move, he embarked on a series of long visits.

During one of these, he wrote the soundtrack to a film called Lieutenant Kijé, a satire set in 1800 tracing the misadventures of a fictional lieutenant who is created when a clerk mis-writes a name in a ledger.

This was Prokofiev’s first time writing for film, and, typically, he had very specific ideas about how he wanted to go about composing for this new genre. “I somehow had no doubts whatever about the musical language for the film,” he wrote.

The Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra asked Prokofiev to adapt his soundtrack into a full orchestral suite, which he did. The suite remains popular in concert halls today.

Romeo and Juliet Suite No. 2, Op. 64ter (1936)

Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet ballet had a rocky beginning.

One of its choreographers resigned from the Kirov Ballet; the project was then moved to the Bolshoi; government bureaucrats were unconvinced about the ballet’s retooled happy ending; and everyone was generally jumpy after a 1936 Stalinist denunciation of renowned composer Dmitri Shostakovich.

Due to these delays, the music was heard before the actual ballet was produced.

That music is, like so much of Prokofiev’s output, both mesmerizing and terrifying. The lumbering bass of the Montagues and Capulets is especially legendary (at 2:45 in the recording above).

Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67 (1936)

One might not have expected this from the infamous enfant terrible of Soviet music, but in 1936, Prokofiev wrote one of the most famous educational works in music history, Peter and the Wolf.

It was commissioned by the director of the Central Children’s Theatre in Moscow. She wanted Prokofiev to write a special symphony for children.

The protagonist Peter plays in a meadow, listening to a whole menagerie of animals symbolized by various instruments.

Peter’s grandfather warns him of a gray wolf who might come to attack him. On cue, the wolf makes an appearance, but with the help of his animal friends, Peter is able to catch it.

Hunters come out of the forest, ready to kill the wolf, but Peter convinces them to put the wolf in a cage and bring it to a zoo instead. They do so, in triumphant, animal-parade formation.

The work has proven to be one of the most popular in the entire repertoire and is often used even today as an introduction to the orchestra and orchestral instruments.

War and Peace, Op. 91 (1941–52)

After the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, Prokofiev teamed up with his new wife, poet/translator Mira Mendelson, to write a massive opera based on Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

He submitted a score to the Soviet Union’s Committee of the Arts in 1942. They wanted more patriotism, but Prokofiev was loath to substantially revise the opera, so he sprinkled in some patriotic marches instead.

Despite the changes, full-throated Party support of the opera was never forthcoming, and the massive project gradually lost steam.

Prokofiev would never actually get to see the entire thing fully staged. But it’s still a fascinating glimpse into how he treated large-scale projects and how politics affected art.

Symphony No. 5 in B♭, Op. 100 (1944)

Prokofiev wrote his fifth symphony in 1944, the summer of the Normandy landings. The long war was reaching a turning point, and this was reflected in his fifth symphony.

Publicly, at least, Prokofiev described the work as “a hymn to free and happy Man, to his mighty powers, his pure and noble spirit.”

He also wrote, “I cannot say that I deliberately chose this theme. It was born in me and clamoured for expression. The music matured within me. It filled my soul.”

At its January 1945 premiere, celebratory artillery was heard in the distance. Prokofiev didn’t begin the performance until the gunfire was over.

Later, the musicians and audience learned that the explosions had been a celebratory signal: Soviet troops had crossed into Germany, signaling a successful invasion. The war ended in Europe a few months later.

Even though this was a work written in a very particular time and place, its themes of overcoming struggle and battered optimism still resonate on a more universal level.

Symphony No. 7, Op. 131 (1951-52)

By the 1950s, Prokofiev’s health was declining. Nevertheless, he still managed one last symphony, his seventh. Somewhat ironically, his final symphonic testament was commissioned by the Soviet Children’s Radio Division.

One can hear a wistful melancholy and a world-weary resignation in this music, even in its more flamboyant passages. The bold aggression of the teenaged Prokofiev has mellowed considerably.

Prokofiev was pushed into altering his work. Originally the ending was quiet and sad. However, a conductor friend told Prokofiev that he should tack on a brief happy ending, which would make him more likely to please bureaucrats and win the Stalin Prize and its 100,000 ruble payout.

Prokofiev reluctantly agreed, but he told the friend, “Slava, you will live much longer than I, and you must take care that this new ending never exists after me.”

Prokofiev’s seventh never won the Stalin Prize, and he died before he could try again with his eighth.

Conclusion

Grave of Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev died on 5 March 1953, about an hour before Joseph Stalin. So many mourners were busy paying tribute to Stalin that his death went largely unnoticed for a long time.

There were no musicians available to play at his funeral, so his family played a recording of his own Romeo and Juliet suite instead. He was sixty-one years old.

Seven of the Most Unruly Audiences in Classical Music History

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

It wasn’t always this way, though. Today we’re looking at seven times when classical music audiences became unruly…and what upset them so much!

1. The Barber of Seville by Gioachino Rossini

Rossini’s The Barber of Seville

20 February 1816 in Rome

Nowadays, we aren’t terribly familiar with composer Giovanni Paisiello, but back in the early nineteenth century, he was a respected rival of Gioachino Rossini.

In 1782, Paisiello wrote an opera called Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville). It was based on a libretto by Giuseppe Petrosellini, which in turn was based on a book by famed creative Frenchman Pierre Beaumarchais.

This opera turned out to be the biggest success of Paisiello’s entire career.

In 1815, Gioachino Rossini also looked to Beaumarchais for inspiration and decided to write his own adaptation of The Barber of Seville. (At least he used a different libretto from Paisiello.)

Obviously, audiences raised an eyebrow: it felt like an attack on beloved Paisiello.

Rossini’s version of Barber premiered in Rome in February 1816, and disaster ensued. There was hissing and jeering through the whole thing (some of it paid for by Paisiello’s allies). To add insult to injury, accidents started happening onstage, too.

However, fortunately for Rossini, the next night’s performance went smoother. Rossini’s Barber of Seville began gaining popularity. (For a long time, though, Paisiello’s was more popular.)

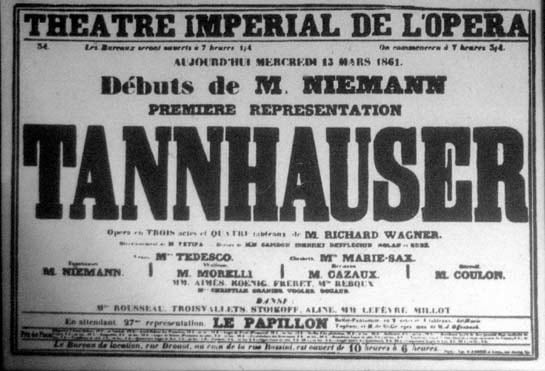

2. Tannhäuser by Richard Wagner

Poster of Tannhäuser performance in Paris

14 March 1861 in Paris

The premiere of Tannhäuser occurred in 1845.

Sixteen years later, in 1861, a performance of Tannhäuser was scheduled in Paris at the Paris Opéra.

This was such an important event that Wagner rewrote the original to conform to Parisian tastes and rules. (For example, operas at the Opéra traditionally had ballet sequences.)

However, instead of inserting the ballet in the second act, as was customary, Wagner wrote it into the story during the first act.

At the first performance, the audience was restless during various portions of the opera. By the second performance, restlessness had evolved into outright disturbances.

The aristocratic Jockey Club was offended by the placement of the ballet in the first act; they were used to it being in the second act so that they could finish eating dinner and arrive late without missing the dancing. (To be clear, by “missing the dancing”, we mean “missing ogling the women dancers.”)

Wagner compounded the problem by refusing to pay the claque. In France, claques were groups of audience members whose reactions could be bought and used to shape public perception of production, a bit like Instagram influencers today. However, Wagner refused to give into the French claque, with disastrous results for Tannhäuser.

During the second night, the Jockey Club disturbed the performance by blowing whistles. After the same thing happened on the third night, Wagner withdrew the opera.

3. Altenberg Lieder by Alban Berg

31 March 1913 in Vienna

Alban Berg, 1920s

This concert was so unruly that it earned its own name: the Skandalkonzert (Scandal Concert).

It happened on 31 March 1913 in Vienna’s Great Hall of the storied Musikverein. The program included works by Anton Webern, Alexander Zemlinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and Alban Berg. It was scheduled to conclude with a performance of Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, but the event was canceled before it could be played.

Two works provoked audiences’ ire: Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 1 and Berg’s Five Orchestral Songs on Picture-Postcard Texts by Peter Altenberg.

The crowd was angry at Schoenberg because a few weeks earlier, he had (rudely, people thought) refused to accept applause after a performance of his Gurrelieder in protest of conservative Viennese taste.

However, the work that broke the public was Berg’s discordant Five Orchestral Songs, of which the second and third were played.

Audiences hated the works. They called in loud voices for Berg to be committed to a mental institution. This was an especially cutting criticism since the writer Peter Altenberg (who had written the texts) was in a mental institution himself at the time.

Soon, audience members began assaulting other audience members. Apparently, concert organizer Erhard Buschbeck slapped an audience member in the face (which resulted in this concert getting the secondary nickname Watschenkonzert, or Slap Concert).

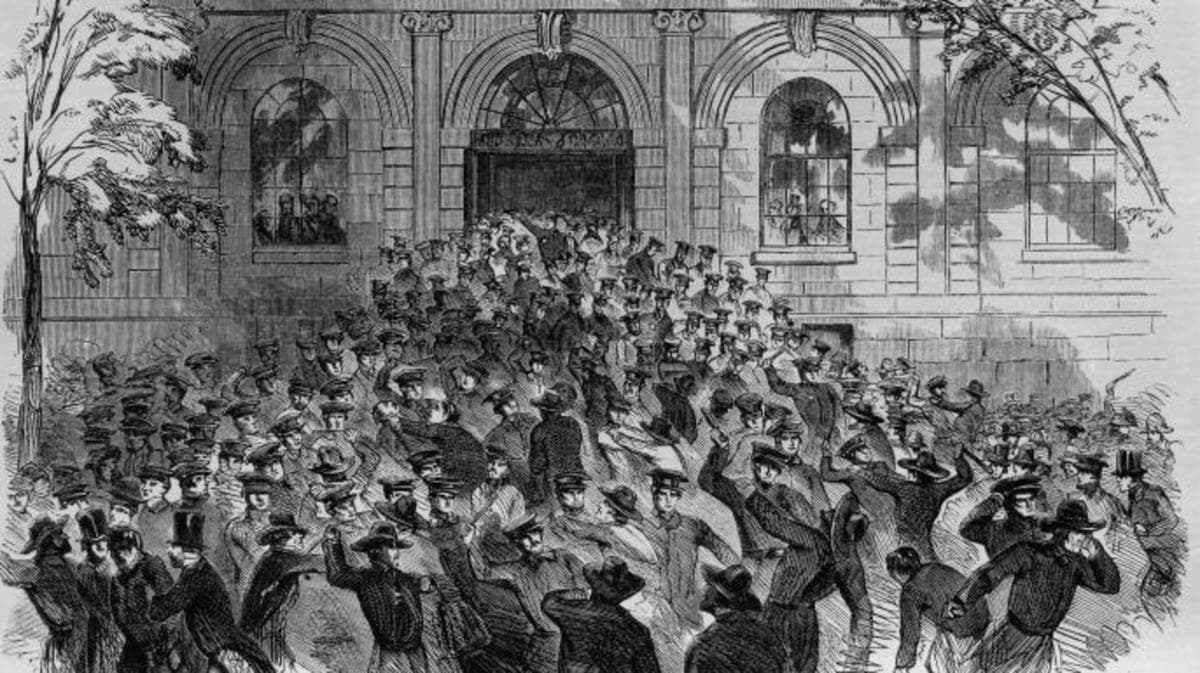

4. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring © chethamsschoolofmusic.com

29 May 1913 in Paris

In May 1913, the daring, fashionable ballet company Ballets Russes mounted their production of The Rite of Spring.

The Rite of Spring was meant to evoke a kind of barbarous “prehistoric” pagan Russia.

Different classes and cliques reacted to the ballet’s music and choreography in different ways, resulting in scattered disturbances in the theater’s auditorium.

Over the years, the stories about this premiere got wilder and wilder. Two years after the performance, author Carl van Vechten claimed that a fellow audience member pounded fists on his head. By the 1920s, music critics were hinting at a more extreme audience reaction than had actually occurred, and by the 1940s, commentators were using the word “riot” for the first time to describe what had happened.

In the end, this concert made this list not because of what actually happened, but because of the famous stories that came out about the night.

5. The Awakening of a City, The Meeting of Automobiles and Aeroplanes by Luigi Russolo

Luigi Russolo, ca. 1916

21 April 1914 in Milan

In 1913, avant-garde painter and Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo wrote a manifesto called The Art of Noises.

He believed that the mechanized sounds of modern urban life could revolutionize concert music, if only they could be accurately and reliably reproduced in a hall.

To help him achieve his goal, he created an orchestra of new instruments called intonarumori, or noise instruments.

These instruments replicated everything from a car engine to a spatula scraping a dish.

On 21 April 1914, the first public concert of the intonarumori was given. People were so upset with his ideas that projectiles were thrown onto the stage even before the curtain opened (Russolo believed that they were students egged on by officials at the Milan Conservatory).

Once the instruments began playing, some of the instrument operators went to physically assault audience members. Apparently, the fights lasted for half an hour, and Russolo continued conducting the ensemble throughout the whole thing.

6. George Antheil Premieres

Berenice Abbott: George Antheil, 1927

4 October 1923 in Paris

American composer George Antheil was known as a bad boy of classical music, unafraid to alienate audiences with his vision of music of the future.

Like many artistic Americans in the 1920s, Antheil moved to Paris and rented an apartment above the famous Shakespeare and Co. bookstore, known as a hub for leading art figures. From there, he got to know and befriend many of the movers and shakers of 1920s Paris.

In 1923, he was asked to make his debut at a performance of the Ballets suédois (Swedish Ballet) in Paris. He performed a handful of works, including his Mechanism, Airplane Sonata, and Sonata Sauvage.

Apparently the audience wasn’t prepared for such abrasive music. To Antheil’s delight, a hubbub developed.

He described it later: “People were fighting in the aisles, yelling, clapping, hooting! Pandemonium! … the police entered, and any number of surrealists, society personages, and people of all descriptions were arrested.” He noted with satisfaction that “Paris hadn’t had such a good time since the premiere of Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps.”

A variety of creative celebrities were present, including Picasso, Cocteau, Milhaud, and Satie (who apparently was heard yelling, “What precision! What precision!”).

The Inhuman Woman 1924

Adding another layer to the fracas is the fact that the riot was staged, as filmmaker Marcel L’Herbier was filming the crowd for his film L’Inhumaine, which required footage of an unruly crowd (starting at around 59:30 in the video above).

7. Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny by Kurt Weill

Kurt Weill

9 March 1930 in Leipzig

In Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical theater work Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, a truck transporting three fugitive criminals breaks down out of the range of law enforcement.

The three criminals decide to found a city and devote it to fulfilling human desires of all kinds: desires for pleasures like money, good food, alcohol, and sex.

People can’t make enough money to sustain themselves in Mahagonny, and deflation eventually hits the city. The government shifts from an anything-goes attitude to prohibiting certain behaviors.

After a hurricane that everyone feared would destroy the city misses Mahagonny, the rules revert back to “anything goes”, demonstrating how the city’s morals change on a dime according to the whims of those in power.

In the hubbub, a citizen named Jimmy Mahoney bets all of his money on a prizefight and loses. He cannot pay his bills and is prosecuted and killed by the state for not having enough money.

The satire’s seemingly anti-capitalist message, combined with Brecht’s sympathy for communist thought, combined to make Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny a controversial work.

Nazi sympathizers were especially unhappy. Austrian critic Alfred Polgar described the night of the premiere: “Belligerent shouts, hand-to-hand fighting in some places, hissing, applauding… enthusiastic fury mixed with furious enthusiasm.”

When the work came to Frankfurt, 150 Nazi sympathizers stormed the auditorium and set off fireworks. A Communist sympathizer was killed later that night.

Shortly after the Berlin run of the opera came to a close, the Nazis gained power in the Reichstag elections, paving the way for Hitler. Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny was banned by the Nazis in 1933.