by Maureen Buja

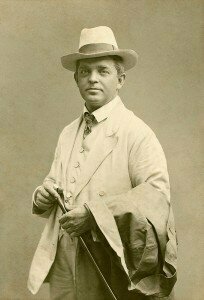

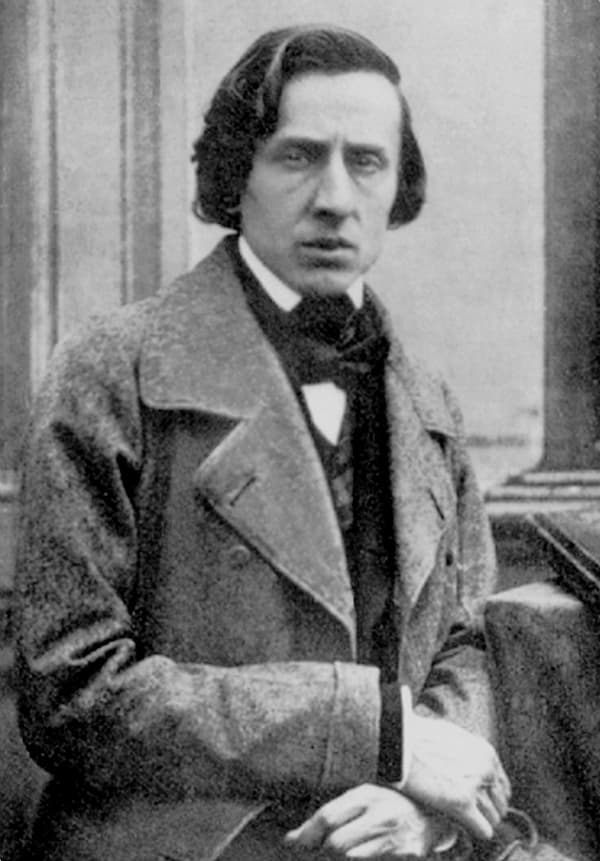

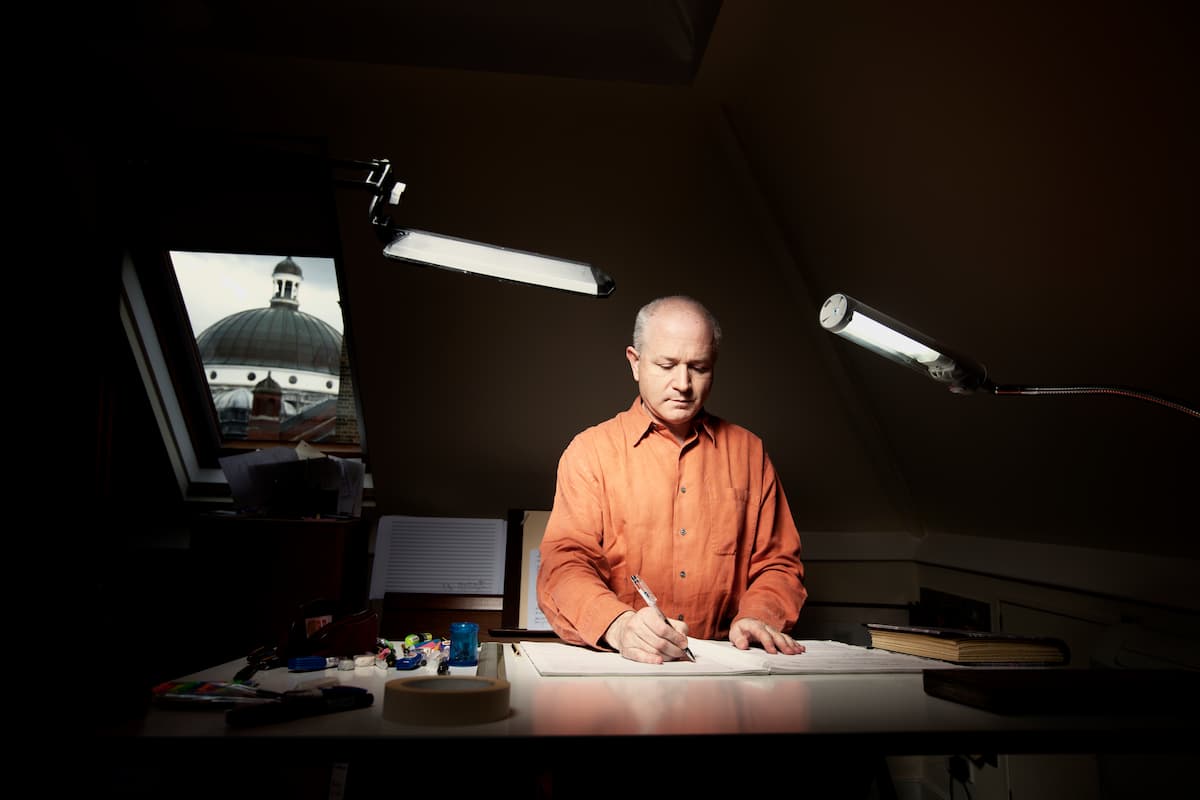

George Benjamin (Photo by Matthew Lloyd)

Martin Crimp

The first is a chamber opera based on the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

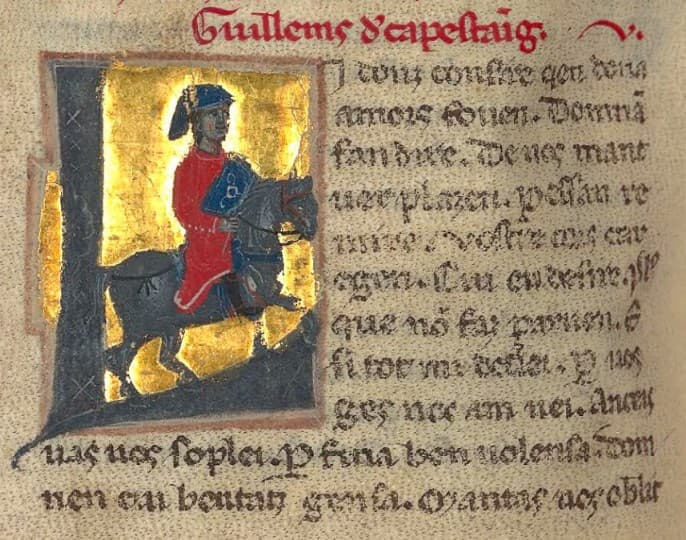

Written on the Skin is set in 13th -century Provence and tells the legend told by the troubadour Guillaume de Cabestanh, where an unfaithful wife is served a dinner of the heart of her lover. When she’s told what she’s eaten, she turns the tables on her murderous husband by declaring that nothing can now remove the taste of her lover’s heart from her. As her husband rushes at her to kill her, she jumps off the balcony to her death.

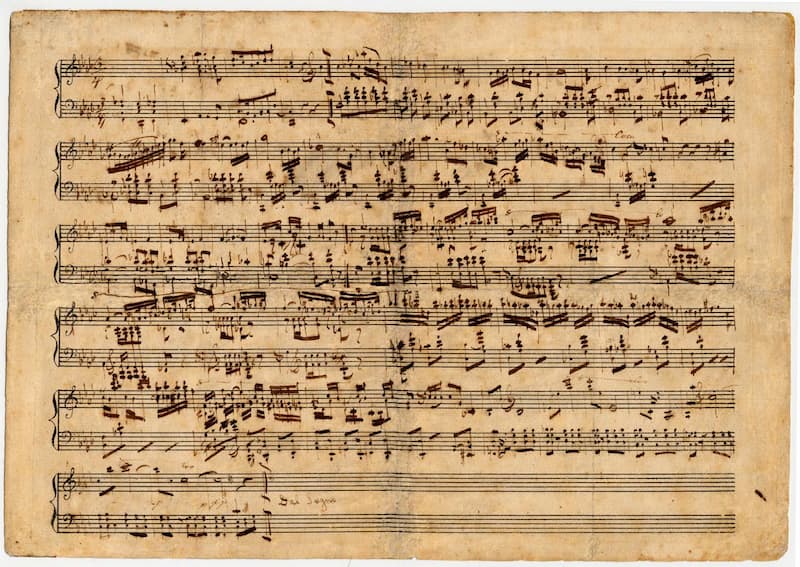

Miniature of Guillem de Cabestany / Guillaume de Cabestanh, 13th century (Gallica: BnF ms. 12473: btv1b60007960, folio 89v)

Lessons in Love and Violence is about the relationship between King Edward II (1284–1327) and Piers Gaveston (1284–1312). Gaveston impressed Edward I, who assigned him to the household of his son, Edward of Caernafon. Edward I kept separating the two because Edward of Caernafon was so extreme in his partiality to Piers. What is unclear is the relationship, variously described with them being friends, lovers, or sworn brothers.

Edward II receiving the English Crown, 1350 (British Library, Royal MS 20 A ii, folio 10)

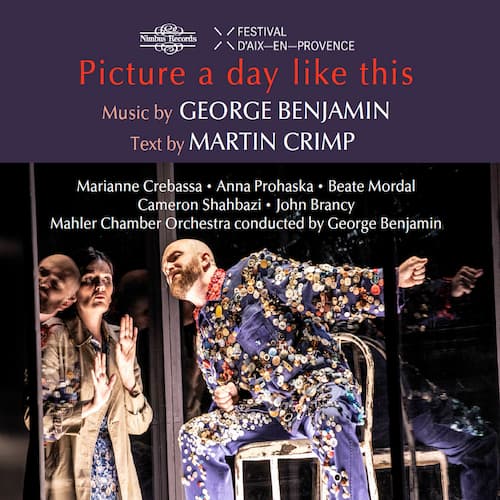

For the 2023 Aix-en-Provence Festival, the new text was for another chamber opera with 5 singers and a 22-member orchestra. The setting is a kind of never-when and fairy-tale like; the characters occupy separate worlds and operate on a kind of ‘dream-like logic’.

Marianne Crebassa in Picture a Day Like This at the Aix-en-Provence festival, 2023 (Photograph by Jean-Louis Fernandez)

A woman’s child dies, and, wrapping the boy in silk, she prepares the body for cremation. People in black arrive to take the body and one tells her: ‘Find one happy person in this world and cut one button from their sleeve – do it before night and your child will live’. She gives the mother (called simply Woman in the opera) a paper list that tells her where to look.

Picture a Day Like This: Scene 1, The Woman and the Death Attendants, 2023 (Festival-d’Aix-En-Provence) (photo by Jean-Louis-Fernandez)

George Benjamin: Picture a Day Like This – Scene 1: The Page (Marianne Crebass, Woman)

It’s Quest Opera, but with a dark and sombre center. The Woman goes off, and first finds 2 lovers, clothes discarded to the side. She asks for a button, as they’re clearly happy in themselves. They agree but then get into an argument about past and current lovers, and jealousy and happiness flee. So does the mother when one of the lovers looks to her to add to his list.

Next, she finds an Artisan. He’s retired and sitting happily in the sun. He confirms he’s happy, but when she asks for a button, he refuses. He was a button maker, and all the buttons on his suit were made with his hands. What he wants is the knife that she should use to cut off the button. What he also wants is chlorpromazine, used to treat psychiatric disorders. As he rolls up his sleeves, she sees all the cuts on his skin from all the times he’s tried to commit suicide. The woman leaves as the nurse leads the unhappy man away.

The Woman (Marianne Crebassa) and the Artisan (John Brancy)

The Composer and her assistant arrive next. The Composer is so busy that happiness has no part in her life.

In the middle, in an Aria, the woman reflects on the hopeless people she’s just met: ‘fools – vain fools – the insane’ when what she wanted was miracles. If dead flowers can come to life, why not her son? She throws away the paper list she was given.

The Collector enters. He says he’s on her list and shows her his collection of paintings: Warhol’s Gold Marilyn, Manet’s last vase of flowers, a book of hours, a Matisse….

Warhol: Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962

(New York: Museum of Modern Art)

He refers to his rooms of artworks as his rooms of miracles. He invites her to take anything that will make her happy…but she must love him. And, he doesn’t have any buttons. She continues her search, paper list back in her hand.

Her last meeting is with Zabelle, a woman seemingly like herself. In a beautiful garden, Zabelle appears when the Woman reads her description on the paper list. She has 2 children playing on the swings; her husband lies half-asleep in the rose garden…can the mother share in this happy and beautiful life? Zabelle says to look again at the garden: shadows are falling, men are at the gate to occupy the park and destroy things, she’s dropped the baby boy, and he seems cold…it’s all an illusion. There is no happiness. Zabelle says that just because her name is on a list doesn’t mean she’s happy because she, in fact doesn’t exist. As she disappears, she twists a button off her sleeve and holds it out, but an invisible barrier separates the two characters.

Picture a Day Like This: Scene 7, The Woman and the Death Attendants, 2023 (Festival-d’Aix-En-Provence) (photo by Jean-Louis-Fernandez)

At the end, the Woman finds herself back where she started, the death attendants are still in the room. They tell her the quest was in vain because

The page is torn from the vast book of the dead –

punched through by grief –

sewn with a human thread –

no one can alter it.

Now do you understand?

The woman smiles at them and bids them to look at ‘the bright button in my hand’.

It’s an intriguing and puzzling story – how things appear on the surface do not survive closer scrutiny. New characters bring different definitions of happiness and different pictures of their hope and despair – lovers are unfaithful, the artisan was broken, the composer was self-obsessed, the collector was lonely, and even the beautiful Zabelle is happy only when it’s not dark. The Woman goes through an impossible journey but still emerges victorious at the end. It was about her own happiness, not others.

The composer said the sequential scenes made it feel like he was writing a new opera for each scene – but, on the other hand, he welcomed the challenge. Another part of the challenge the composer and writer set each other is to find something new and different for each work: fairy tales to stories of the troubadours to royal scandals, and now a dream quest – they couldn’t be more different in the subject if they tried!

The opera closes ambiguously. In the final scene, Zabelle describes the change from the day’s beauty to the night’s horrors, the Woman confronts the women who gave her the impossible quest and shows them her button. Does she get her son back? It’s not clear.

George Benjamin: Picture a Day Like This

Nimbus Records: NI 8116

Release date: 6 September 2024

Official Website