by Georg Predota, Interlude

Chopin’s romantic intensity was amply reflected in his music, which combined a gift for melody, an adventurous harmonic sense, an intuitive understanding of formal design, and a brilliant piano technique. He started his career as a pianist but abandoned concert life early on to explore the expressive and technical characteristics of the instrument. Chopin, more so than any other composer of his day, went on a journey of infinite discovery.

Formative Years

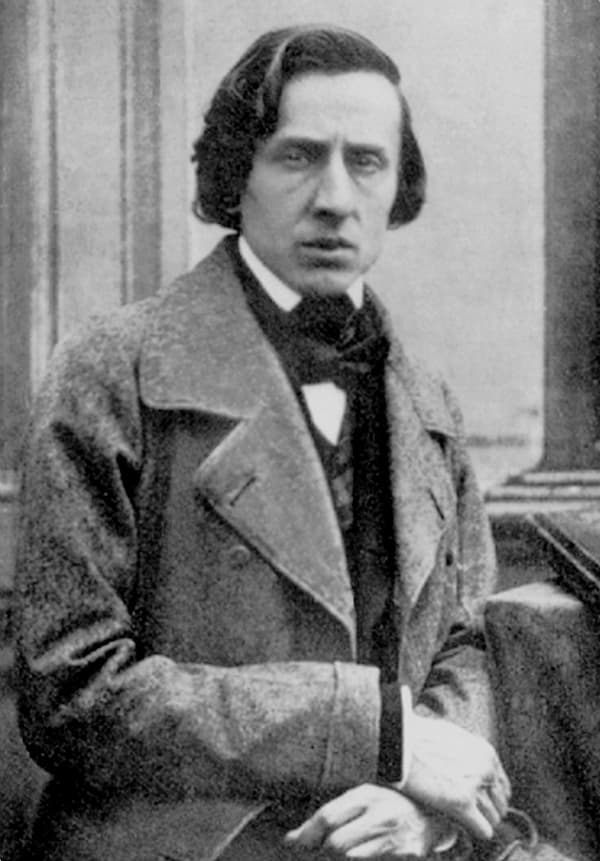

Frédéric Chopin in 1849

The biography of Chopin’s early years is pretty well established, as he was born in Żelazowa Wola and grew up in Warsaw. He clearly was a child prodigy and started giving public concerts at the age of 7. Remarkably, around this time, he also started to compose by focusing on polonaises, variation sets, and rondos. The Chopin scholar Jim Samson writes, “these works show the influence of the brilliant style of post-Classical pianism associated with composers such as Hummel, Weber, Moscheles, and Kalkbrenner.”

The young composer managed in a very short time to assimilate many of the standard gestures and figuration, and he already created pieces of considerable accomplishments. It has often been suggested that Chopin’s unique sound world emerged fully formed from the start, yet much of his idiomatic figurations are closely modelled on common devices used by pianist-composers. The young Chopin was clearly preparing himself for a career on the concert platforms and salons of Europe’s cultural capitals.

Warsaw

Manor house in Żelazowa Wola, Chopin’s birthplace

The young pianist-composer also looked toward the traditional music of the Mazovian plains of central Poland, encoding the rhythmic and modal patterns and the characteristic melodic intonations in his early mazurkas. Although he had some personal contacts with Polish folk music, Chopin mediated the genre through salon dance pieces and the world of the traditional folk ensemble. As Samson writes, “At a very early stage, Chopin made this genre his own, and even the earliest efforts project the unmistakable character of the mature mazurka.”

To complete his years of apprenticeship, Chopin started a process of radically reworking the forms, procedures, and materials drawn from the Viennese Classical composers. We find his first Piano Sonata Op. 4 and the Piano Trio Op. 8. However, the two major works of the last Warsaw periods are the piano concertos, the first extended compositions that established a place in the repertory.

A critic commented on Op. 11 as follows, “On the whole, the work was brilliant and well written but without any particular originality or depth except for the main theme and middle second of the Rondo, which display a unique charm in their peculiar combination of melancholy and light-hearted passages.”

Paris

Henryk Siemiradzki: Chopin concert

By the time Chopin arrived in Paris in the autumn of 1831, the primary genres of his oeuvre, the mazurka, nocturne, etude, and waltz, were already in place. The mazurka, in particular, now took on some added meaning. Chopin claimed the genre for art music, “investing the salon dance piece with the complexity and sophistication that immediately transcended its peasant origins.”

It becomes a stylised folk idiom, and as Jim Samson writes, “it is fitting that his nationalism should have expressed thus, through the renovation of a simple dance piece rather than through the more usual channels of opera and programmatic reference.”

Chopin’s engagement with an expressive aesthetic emerged most prominently in the piano nocturne. In fact, it was the genre that launched Chopin’s entire musical career in the fashionable salons of the city. This glimpse into the highly expressive world of Chopin’s music was greatly facilitated by the development of the sustaining pedal, “enabling those wide-spread arpeggiations supporting an ornamental melody which we recognise today as the archetype of the style.”

As such, Chopin was able to draw uniquely delicate and seductive sonorities, extraordinary bel canton elaboration of melody, and rich harmonic subtlety from the instrument. Chopin set the standard with his Op. 9, but already in the Op. 15, it becomes clear that the title “nocturne” could be attached to music of highly varied formal and generic schemes.

Chopin composed his set of 12 Etudes Op. 10 in Warsaw, Vienna, and his early Paris years. This major achievement turned mundane and boring finger exercises into a veritable art form. Chopin changed the entire meaning of what an etude should actually be. Of course, each one explores a different pianist problem area like arpeggios, scales, crossing fingers and hands, and all kinds of finger busters, but these pianistical problems are encased within musical shapes and ideas that transcended the previous meaning.

The significance of the Chopin Op. 10 is twofold. Chopin clearly transcended the brilliant style and directly confronted virtuosity while showcasing and encapsulating his unique musical style. Chopin achieved a balance between technical and artistic aims, or as Robert Schumann put it, “imagination and technique share dominion side by side.”

Consolidation

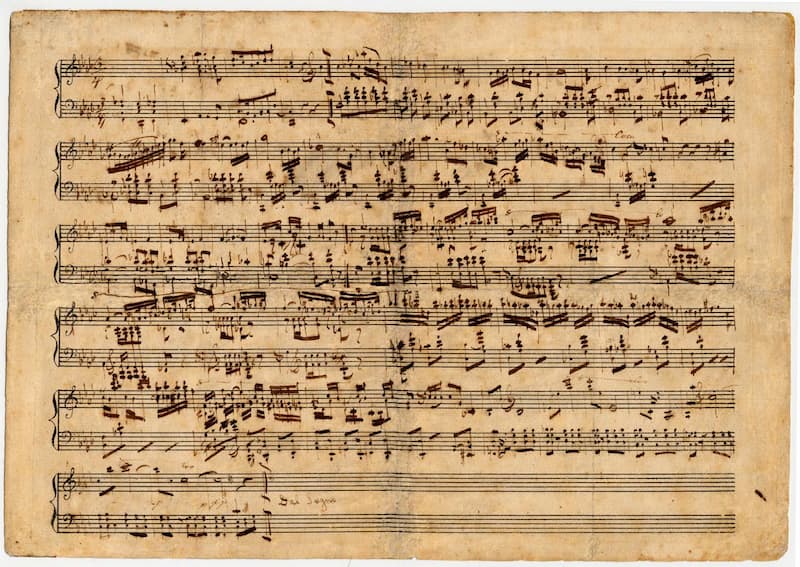

Chopin’s Polonaise autograph score

Chopin’s piano music acquired its characteristic sound through the mazurkas, nocturnes, and etudes. As his personal style matured, Chopin sought to place his conception of melody, figuration, and harmony into more extended forms. We find the result in the 2 Polonaises Op. 26, the first Scherzo, Op. 20, and the first Ballade, Op. 23. For each of these three genres, Chopin followed up with three additional opuses. We also must mention the 24 Preludes of Op. 28, the first set of pieces by that name, which are presented as a cycle of self-contained pieces, each of which can stand alone.

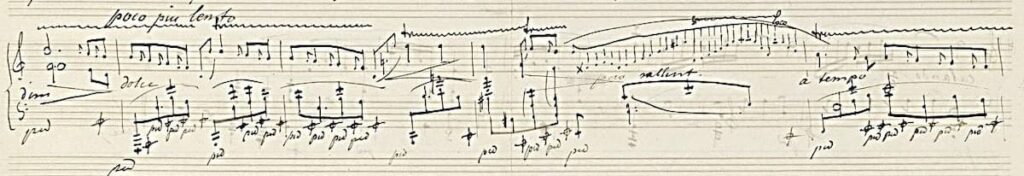

Chopin’s handwriting on his Nocturnes, Op. 62

While Chopin had consolidated some of the genres established during the Vienna and early Paris years in his pre-Nohant years, his relationship with George Sand gave the music a new tranquillity. Working primarily in Nohant during the summer, Chopin composed more deliberately and with a sense of growing self-doubt. Scholars suggest that the early 1840s “have often been described as a turning point in his creative evolution, marked by a renewed interest in counterpoint, by a more sparing and structurally focused ornamentation and by a strengthening command of structure.”

Eloquent Simplicity

Chopin’s last piano displayed at the Fryderyk Chopin Museum in Warsaw

Chopin had suffered from serious and chronic health problems throughout his short life. In his teens, he suffered from frequent respiratory infections and countless episodes of bronchitis and laryngitis. He suffered through a bout of influenza in 1837, and although his doctor assured him that he was not suffering from tuberculosis, Chopin’s health rapidly deteriorated after 1840, with the composer weighing only 45 kilograms.

An army of doctors tended to his physical ailments, including cough, fever, painful wrists and ankles, haemoptysis, hematemesis and ankle oedema. Chopin’s condition deteriorated further at the beginning of October 1849, and he died on the morning of October 17, 1849, “after having been unconscious for 24 hours.” Despite his constant health struggles, “Chopin reached a new plateau of creative achievement, marked by an eloquent simplicity which severely excludes the extraneous and the gratuitously ornamental.”