by Georg Predota, Interlude

Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983) was the sole female member of the intriguing group of young French composers eventually known as “Les Six.” Her association with “Les nouveaux jeunes” aside, Tailleferre was a prominent and prolific composer writing in a wide range of musical genres. Her memorable music for opera and ballet is augmented by piano concertos, symphonic works, solo piano pieces, music for small ensembles and well over 40 movie soundtracks. She left behind an extensive body of works representing almost 70 years of compositional engagement and over time forged a distinctive musical voice that valued clarity, spontaneity and charm. Tailleferre strongly believed that a composition would lack artistry if a listener couldn’t identify a composer’s style after three bars. “I write music because it amuses me,” Tailleferre suggested. “It’s not great music, I know, but it’s gay, light-hearted music which is sometimes compared with that of the “petits maîtres” of the 18th century. And that makes me very proud.”

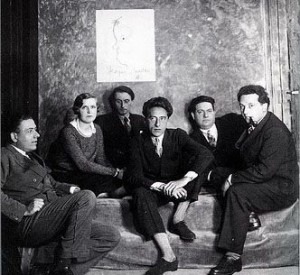

Currently, Tailleferre is considered the “most important French woman composer of all time.” This appreciation, however, has only been forged during the 21st- century, and its cultural reinterpretation and revival of her music. Born Marcelle Taillefesse at Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, Val-de-Marne, France, her early years were marked by persistent struggles against her father. He considered music an unworthy pursuit, and a “woman studying music” he once remarked, “was no better than her becoming a streetwalker.” She eventually changed her name to spite her father, but never forgave him for his inflexible attitude towards her artistic gifts. Embittered, “she is said to have regarded his demise in 1916 as something of a relief.” Despites her father’s strong opposition, she began her study of piano and solfege at the Paris Conservatory in 1912, and immediately won various prizes in counterpoint and harmony. Tailleferre quickly caught the eyes of her fellow students Darius Milhaud, Georges Auric and Arthur Honneger. Upon the publication of her first string quartet in 1918, she was welcomed as a major talent into the private musical club that eventually blossomed into “Les Six.”

Les Six © s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com

Tailleferre rubbed shoulders with the greatest creative minds of her time. She was a close friend of Maurice Ravel and Erik Satie, a favorite of Jean Cocteau and acquainted with Aaron Copland. Her circle of friends included Igor Stravinsky, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Guillaume Apollinaire, George Balanchine and Sergei Diaghilev, among numerous others. She once remarked that Picasso gave her the “best lesson in composition” she ever received as he told her to “constantly renew yourself; avoid using the recipes that you have already found.” Many of her most important works emerged during the 1920’s, including the First Piano Concerto, the Harp Concertino, the ballets Le marchand d’oiseaux and La nouvelle Cythère, which was commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes. These highly successful and critically acclaimed compositions were followed by the Concerto for Two Pianos, Chorus, Saxophones, and Orchestra, the Violin Concerto, the opera cycle Du style galant au style méchant, the operas Zoulaïna and Le marin de Bolivar, and La cantate de Narcisse, in collaboration with esteemed French poet Paul Valéry.

Wanting to breathe new life into her career, Tailleferre moved to New York in 1925. Leopold Stokowski, Willem Mengelberg, Serge Koussevitzky, and Alfred Cortot performed her compositions, and her short-lived marriage to the New Yorker magazine artist Ralph Barton further enhanced her celebrity status. Musically reinvigorated and her marriage in tatters she returned to France, but World War II brought her once again to the United States. The war years severely stifled her musical creativity and productivity, and affected a fundamental cultural and artistic dislocation. Upon her return to France in 1946 Tailleferre continued to compose orchestral works, ballet and chamber music. However, most of these works were published posthumously with a substantial number of her compositions still unknown today. She nevertheless continued to compose until a few weeks before her death in 1983, and her last work Concerto de la fidelité pour coloratura soprano et orchestra premiered at the Paris Opera in 1982. Her music never failed to give voice to an extended French artistic tradition, and the seductive grace and charm of her work are perhaps best summed up by Cocteau’s famous assessment of Tailleferre “as the musical equivalent to painter Marie Laurencin.”

Moderato (It.)

Moderato (It.) In

In