Today we’re looking at the life and career of Hélène Jourdan-Morhange: her early education, the tragedies that shattered her life, her profoundly influential friendships with Ravel and other composers, and her groundbreaking later work as a writer and radio producer.

Childhood and Early Music Studies

Hélène Jourdan-Morhange

Hélène Morhange was born on 30 January 1888.

She began playing the violin as a young child. She was prodigiously gifted, entering the Paris Conservatoire in 1898 at the age of ten.

Among her fellow students was legendary pianist Alfred Cortot.

From the age of thirteen, her teacher was Édouard Nadaud, who taught at the Conservatoire between 1900 and 1924.

In 1906, she won the Conservatoire’s first prize in violin. She was just eighteen years old.

Performing in Parisian Salons

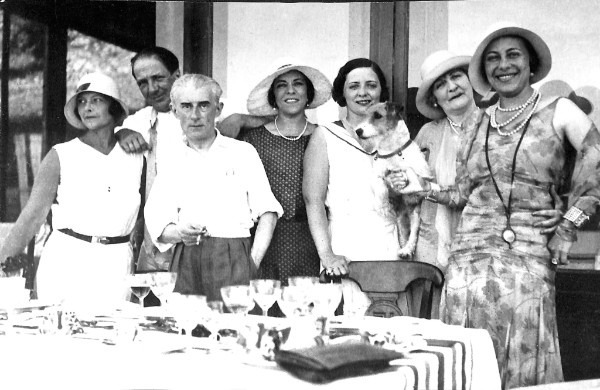

Left to right: Luc-Albert Moreau, Jourdan-Morhange, Madeleine Grey, Germaine Malançon, and Maurice Ravel (1925)

As a young woman, she played in some of Paris’s most famous salons.

These private performances advertised musicians’ abilities to fellow artists and wealthy patrons.

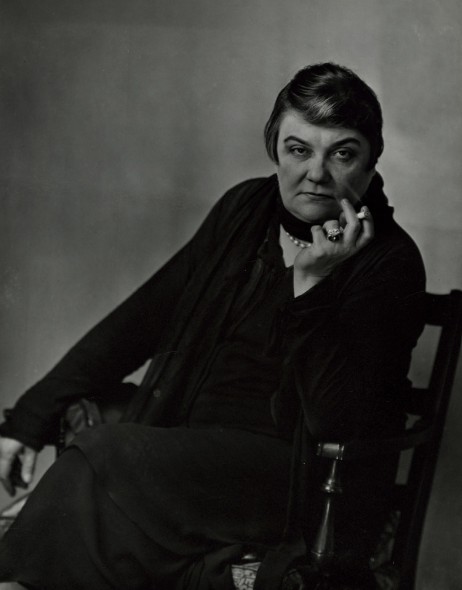

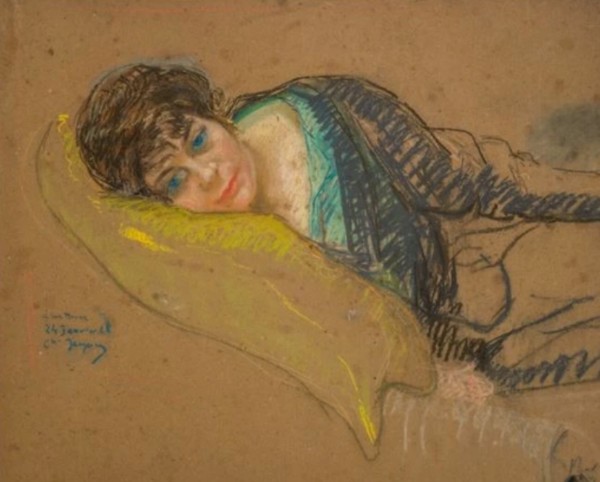

Eugènie Murat

One famous salon that Morhange played at belonged to Princess Eugènie Murat, an eccentric, wealthy woman whose sapphic tendencies during her widowhood were well-known.

Like many in her social set, Princess Murat delighted in using powerful drugs like hashish and cocaine. According to one legend, she rented a submarine so she could partake in private.

Winnaretta Singer

Morhange was also a regular at the salon of Princess Edmond de Polignac, an American heiress with the maiden name of Winnaretta Singer.

A lesbian herself, Princess Polignac entered into a friendly lavender marriage with the gay Prince Edmond de Polignac.

After their marriage, she used her money and her newfound social status to entertain – and seduce – the cream of musical Parisian society.

Thanks to these women, Morhange was on the front lines of Parisian art, literature, and music from an early age.

Marriage and War

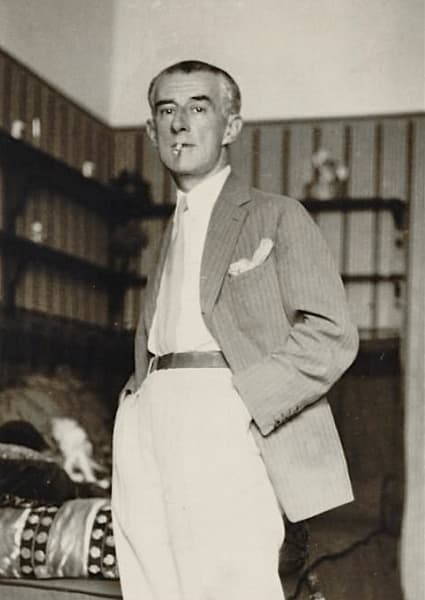

Hélène Jourdan-Morhange and her husband Jacques Jean Raoul Jourdan

In 1913, at the age of twenty-five, Morhange married painter Jacques Jean Raoul Jourdan. (Interestingly, she hyphenated her surname, instead of changing it entirely…a somewhat unusual choice in the 1910s.)

The summer of the following year, World War I began, and he left to fight.

He died in March 1916 at the Battle of Verdun, one of the longest battles of the war.

Jourdan-Morhange was devastated, and his violent loss would haunt her for years.

During the war, she partnered with pianist Juliette Meerowitch, a student of Cortot’s who was well-known for championing the work of Erik Satie.

Their friendship became deeply meaningful. She began processing the death of her husband and the trauma of the war by talking to Meerowitch and playing with her.

Befriending Ravel

Another important new friend was Maurice Ravel. She met him after performing Ravel’s piano trio, a piece that he had rushed to finish before the war began, fearing he wouldn’t survive the conflict. (In fact, he was so convinced that he was about to die that he dryly referred to the trio as being “posthumous.”) He was deeply impressed by her playing and musicianship.

Hélène Jourdan-Morhange (on the left) with Maurice Ravel

When he was working on his orchestral showpiece La Valse, he wrote her a letter asking a question about how he should orchestrate a particular part.

Tragically, in 1920, two years after the end of the war, Jourdan-Morhange’s recital partner, Juliette Meerowitch, died suddenly while touring in Brussels.

After this second great loss, coming so close on the heels of the loss of her husband, Jourdan-Morhange began spending more time with Ravel. At the time, Ravel was also in mourning after the death of his beloved mother, so he understood her grief. And of course, both musicians were grappling with the loss of many of their friends in the war.

It’s no surprise that they ended up becoming good friends and colleagues. There are rumours that Ravel thought about marrying her, but there’s no evidence they ever embarked on a romantic relationship.

Inspiring Ravel

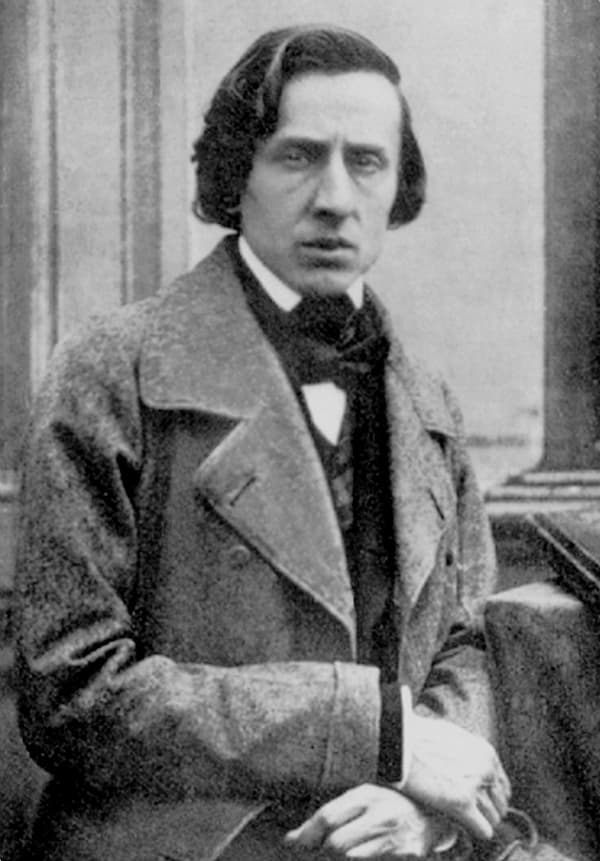

Portrait of Hélène Jourdan-Morhange by her husband Jacques

Around this time, Ravel was asked to write a piece to honour Claude Debussy, who had died of cancer in the closing months of the war.

He began the work in 1920 but continued working on it over the following two years.

In 1922, Jourdan-Morhange premiered the resulting piece: Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello, sometimes known as his Duo, with cellist Maurice Maréchal.

Ravel’s Sonata for Violin and Cello

He also began his G-major violin sonata.

Historian Jillian C. Rogers has an intriguing theory about these and other Ravel works in her 2021 book Resonant Recoveries: French Music and Trauma Between the World Wars. She believes that the repetitive, flowing rhythms that became integral to Ravel’s musical language originated, in part, from a desire to provide music to his friends that was soothing to practice. Those flowing, repetitive rhythms are in full evidence in the violin sonata.

The sonata took five years to finish, only finally coming to fruition in 1927.

Unfortunately, by that time, Jourdan-Morhange couldn’t premiere it. She was enduring yet another tragedy: chronic pain that no doctor could diagnose, which was keeping her from playing the violin.

It has been theorised that this pain might have originated from arthritis, rheumatism, or an overuse injury.

But whatever the cause, it was severe and long-lasting enough to permanently remove her from the concert stage.

She was forced to make do with accepting the work’s official dedication. Violinist Georges Enescu ended up premiering it, with Ravel on the piano.

Ravel’s Death

After finishing the violin sonata, Ravel did not have many good years left in him.

In October 1932, he was in a taxi accident that appears to have caused or triggered neurological issues.

(Some historians have suggested that he had Pick’s disease, an incurable early-onset dementia similar to Alzheimer’s.)

By 1937, he could no longer compose. He complained bitterly to his friends and colleagues: he could hear music in his head, but could no longer write it down. He told Jourdan-Morhange that he was frustrated because he felt he had so much left to give the world musically.

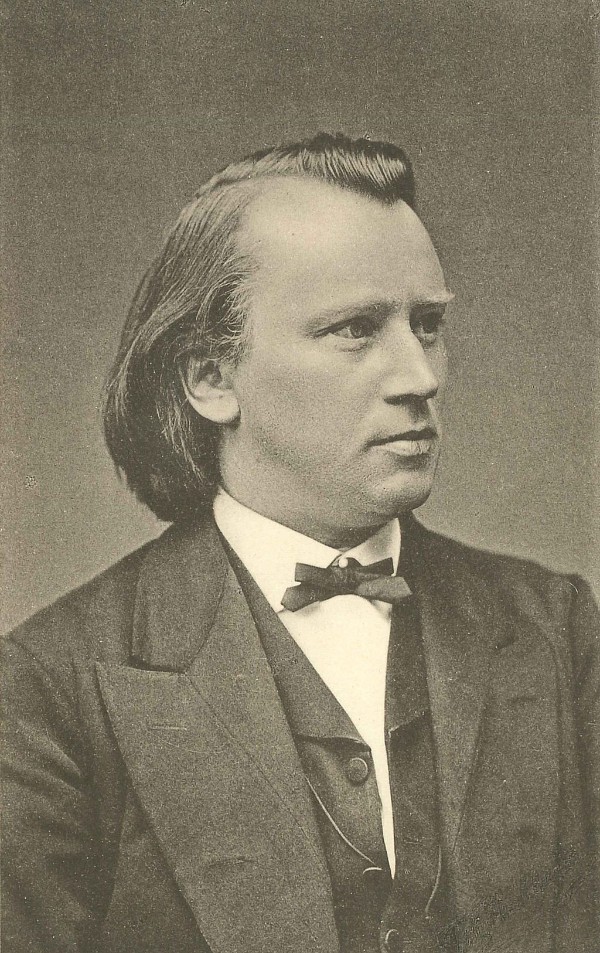

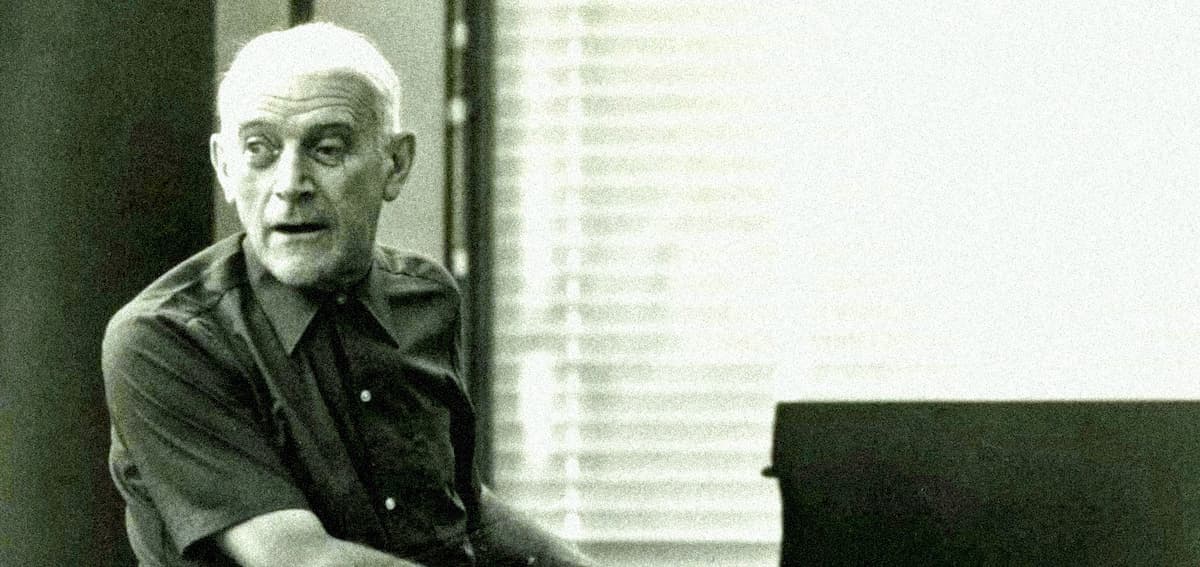

Maurice Ravel

Although it was difficult to see her dear friend in such pain, Jourdan-Morhange spent as much time as she could with him in his final illness.

She later spoke about the long walks they took together in nature. He could identify birds with ease based on their songs, but hearing music at concerts became extremely difficult and even traumatic for him.

His condition worsened. After a failed exploratory brain surgery, Ravel died in December 1937.

A Second Marriage and a New Career

After twenty years of living with painter Luc-Albert Moreau, Jourdan-Morhange married him in 1946.

During the interwar period, while living with Moreau, Jourdan-Morhange had become very close to author Colette, who lived nearby.

Colette encouraged Jourdan-Morhange that even if she could no longer play the violin, she could at least write about music.

So in addition to teaching, Jourdan-Morhange began writing, submitting reviews and reminiscences to a variety of different French journals.

After World War II ended, she also began producing radio programs for RDF (Radiodiffusion française).

Partnership with Perlemuter

Vlado Perlemuter

In 1950, she produced and co-hosted a radio series with pianist Vlado Perlemuter, who had studied Ravel’s entire piano output with the composer in his early twenties.

During the radio shows, Perlemuter would play the works, and he and Jourdan-Morhange would both talk about what interpretive ideas Ravel had in mind.

Perlemuter playing Ravel’s Toccata from Le tombeau de Couperin

The transcriptions and translations of these programs were later published as Ravel According to Ravel. They serve as an important window into his famously exacting ideas.

In the late 1940s, Jourdan-Morhange became one of the founding members of the Maurice Ravel Foundation, which sought to memorialise his life and career.

She once wrote of Ravel, “His friends and those close to him looked for him in his work, sometimes remembering him in a rhythm, an unpredictable harmony, the fleeting memory of a look, a tender expression, where their lost friend was wholly revealed to them.”

Remembering Her Musical Colleagues

Hélène Jourdan-Morhange

Her memories of Ravel and the other great composers whose works she inspired and championed contain valuable insights.

During the radio program with Perlemuter, she said:

“So Ravel used to say everything that had to be done, but above all…what was not to be done. No worldly kindness restrained him when he was giving his opinion… Having worked on the Sonata, the Duo and the Trio with Ravel when I was a violinist, I recognise in Perlemuter’s interpretations all the idiosyncrasies, all Ravel’s wishes: exaggerated swells, crescendi which explode in anger, turns which die on a clear note, the gentle friction of affectionate cats…and in all this fantasy, strict time in expression and rigour even in rubato.”

Of course, Ravel wasn’t the only composer she knew well. She wrote down a couple of evocative memories about composer Gabriel Fauré, too:

“It would be difficult for me to describe his special wishes in the way that I could with Ravel. Just one directive stands out, and very strongly so: play in time without slowing, without even taking time to ‘prepare’ those voluptuous harmonies that the slightest hesitation might underline for the audience’s ears… Fauré, completely kind as he was, could be terribly direct with those who struck him as snobbish – most usually fashionable ladies.”

However, when it came to the music of French composer Pierre Boulez, she was puzzled. In 1950, she wrote in a review:

“It’s difficult for me to follow Pierre Boulez, because I admit I was so bored by his 30-to-35-minute-long sonata that I forbid myself from talking about it… I don’t understand. I am one of those listeners who demand from music what the Greek philosophers called a ‘moral force.’ It was Aristotle who saw people’s faces relax and their expressions lighten when a performance was beautiful… Well, the audience the other evening didn’t radiate goodness; rather, it was boiling.”

Conclusion

Hélène Jourdan-Morhange died on 15 May 1961. She was 73 years old.

Much is still left to rediscover about her life and career, as well as the profound influence she had on Ravel and the other Parisian composers who surrounded them both.

But even with the sketchy biographical information we have about her today, it is clear that she was a major force in French classical music between the wars. She should be remembered and celebrated more often.