Born: June 17, 1882 Lomonosov Russia

Died: April 6, 1971 (aged 88) New York City New York

Awards And Honors: Grammy Award (1967) Grammy Award (1962) Grammy Award (1961)

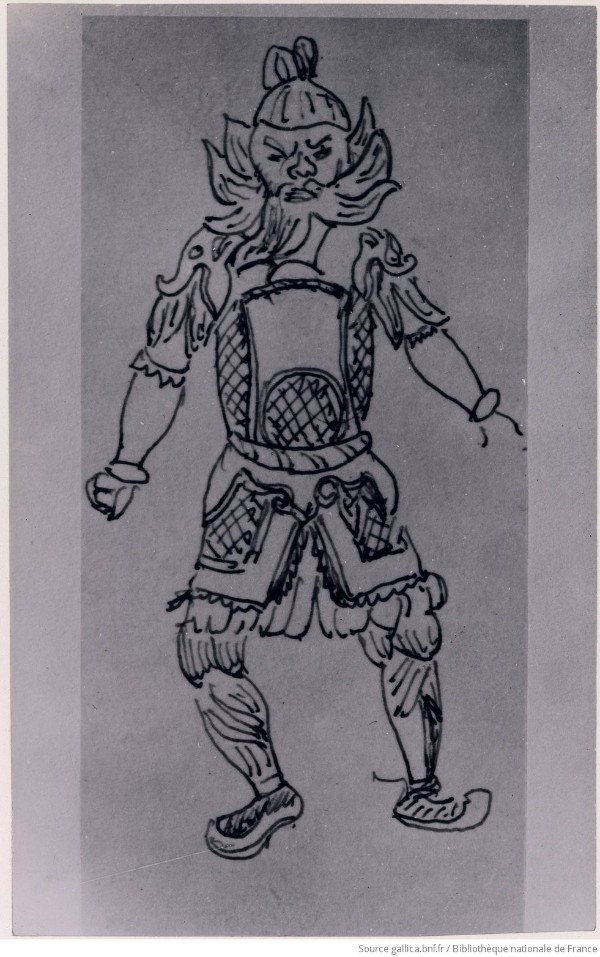

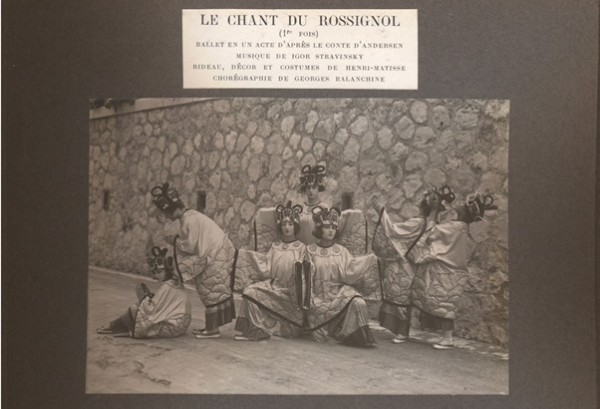

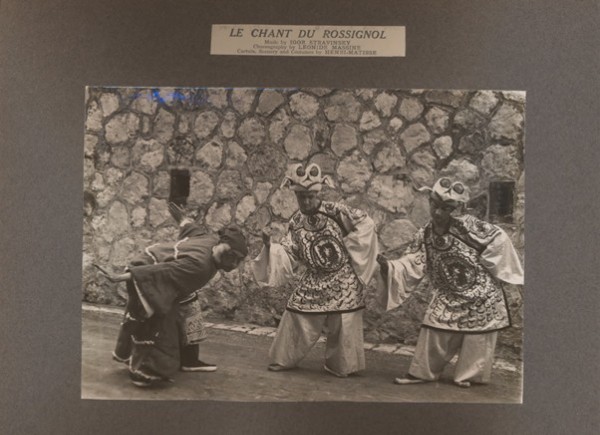

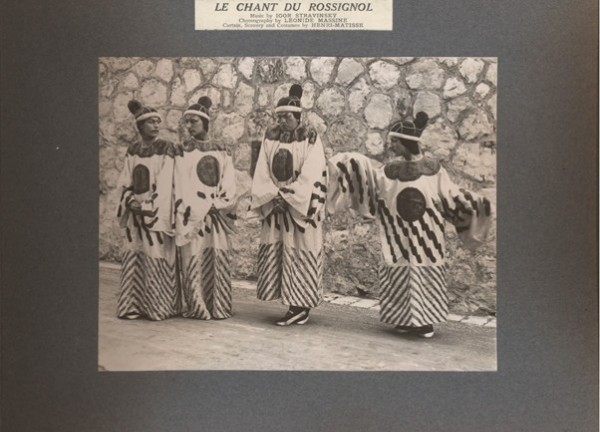

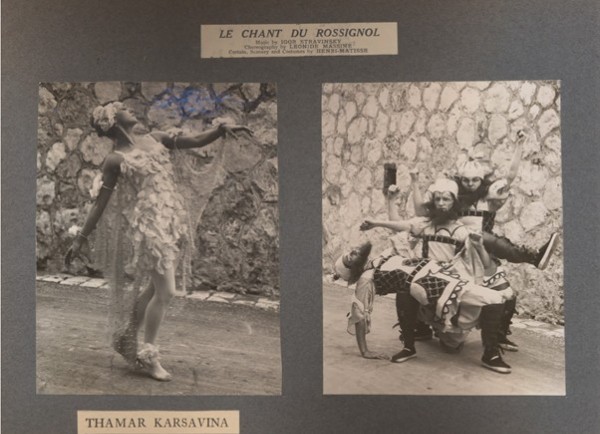

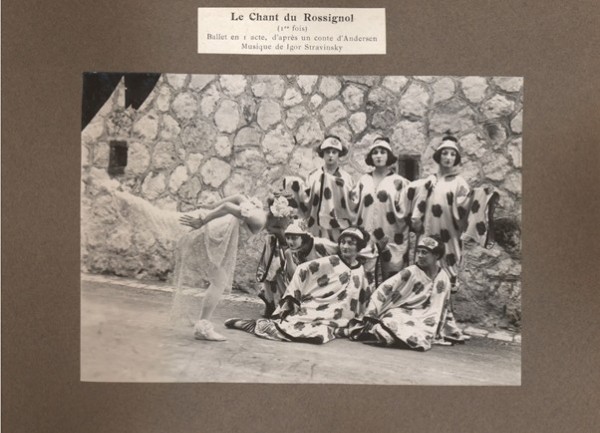

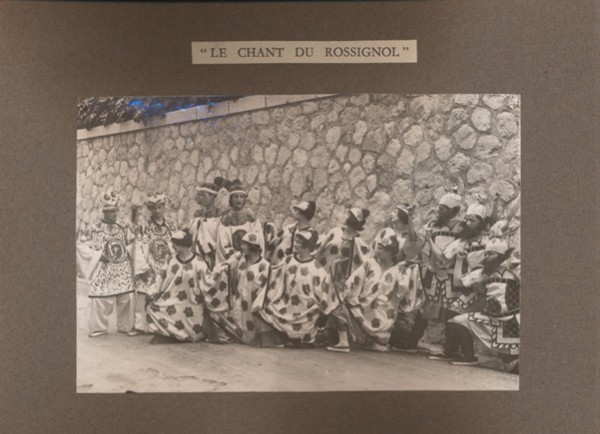

Notable Works: string quartet “Oedipus Rex” “Persephone” “Requiem Canticles” “Symphony in C” “Symphony in Three Movements” “The Firebird” “The Flood” “The Rake’s Progress” “The Rite of Spring” “The Song of the Nightingale” “The Wedding” “Threni”

Movement / Style: Neoclassical art

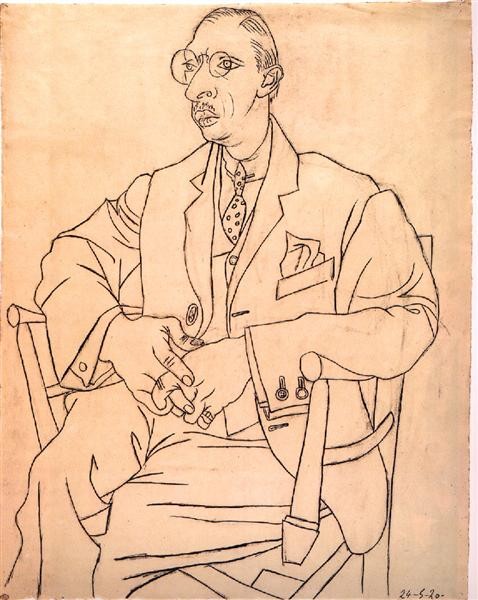

Igor Stravinsky, in full Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, (born June 5 [June 17, New Style], 1882, Oranienbaum [now Lomonosov], near St. Petersburg, Russia—died April 6, 1971, New York, New York, U.S.), Russian-born composer whose work had a revolutionary impact on musical thought and sensibility just before and after World War I, and whose compositions remained a touchstone of modernism for much of his long working life. He was honoured with the Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal in 1954 and the Wihuri Sibelius Prize in 1963.

Life and career

Stravinsky’s father was one of the leading Russian operatic basses of his day, and the mixture of the musical, theatrical, and literary spheres in the Stravinsky family household exerted a lasting influence on the composer. Nevertheless his own musical aptitude emerged quite slowly. As a boy he was given lessons in piano and music theory. But then he studied law and philosophy at St. Petersburg University (graduating in 1905), and only gradually did he become aware of his vocation for musical composition. In 1902 he showed some of his early pieces to the composer Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov (whose son Vladimir was a fellow law student), and Rimsky-Korsakov was sufficiently impressed to agree to take Stravinsky as a private pupil, while at the same time advising him not to enter the conservatory for conventional academic training.

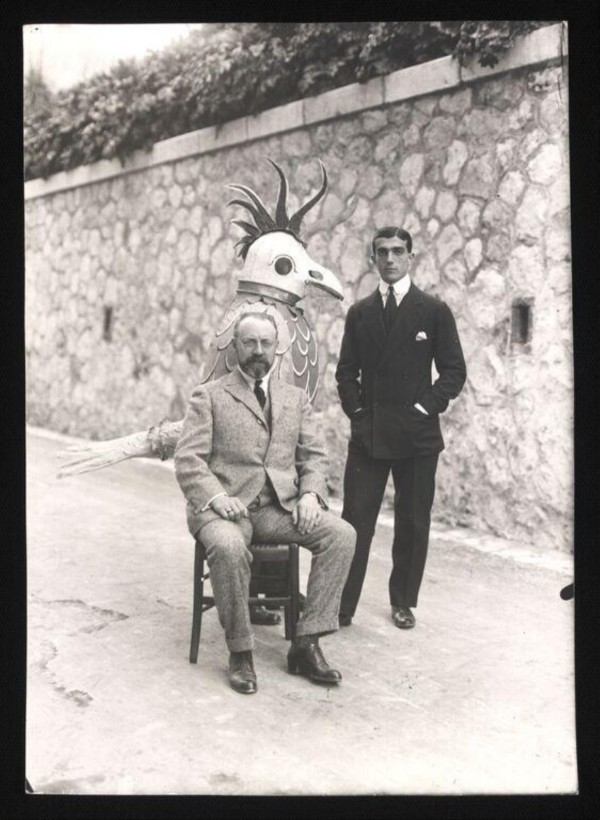

Rimsky-Korsakov tutored Stravinsky mainly in orchestration and acted as the budding composer’s mentor, discussing each new work and offering suggestions. He also used his influence to get his pupil’s music performed. Several of Stravinsky’s student works were performed in the weekly gatherings of Rimsky-Korsakov’s class, and two of his works for orchestra—the Symphony in E-flat Major and The Faun and the Shepherdess, a song cycle with words by Aleksandr Pushkin—were played by the Court Orchestra in 1908, the year Rimsky-Korsakov died. In February 1909 a short but brilliant orchestral piece, the Scherzo fantastique was performed in St. Petersburg at a concert attended by the impresario Serge Diaghilev, who was so impressed by Stravinsky’s promise as a composer that he quickly commissioned some orchestral arrangements for the summer season of his Ballets Russes in Paris. For the 1910 ballet season Diaghilev approached Stravinsky again, this time commissioning the musical score for a new full-length ballet on the subject of the Firebird.

The premiere of The Firebird at the Paris Opéra on June 25, 1910, was a dazzling success that made Stravinsky known overnight as one of the most gifted of the younger generation of composers. This work showed how fully he had assimilated the flamboyant Romanticism and orchestral palette of his master. The Firebird was the first of a series of spectacular collaborations between Stravinsky and Diaghilev’s company. The following year saw the Ballets Russes’s premiere on June 13, 1911, of the ballet Petrushka, with Vaslav Nijinsky dancing the title role to Stravinsky’s musical score. Meanwhile, Stravinsky had conceived the idea of writing a kind of symphonic pagan ritual to be called Great Sacrifice. The result was The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps), the composition of which was spread over two years (1911–13). The first performance of The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs Élysées on May 29, 1913, provoked one of the more famous first-night riots in the history of musical theatre. Stirred by Nijinsky’s unusual and suggestive choreography and Stravinsky’s creative and daring music, the audience cheered, protested, and argued among themselves during the performance, creating such a clamour that the dancers could not hear the orchestra. This highly original composition, with its shifting and audacious rhythms and its unresolved dissonances, was an early modernist landmark. From this point on, Stravinsky was known as “the composer of The Rite of Spring” and the destructive modernist par excellence. But he himself was already moving away from such post-Romantic extravagances, and world events of the next few years only hastened that process.

Britannica Quiz Music: Fact or Fiction?

Stravinsky’s successes in Paris with the Ballets Russes effectively uprooted him from St. Petersburg. He had married his cousin Catherine Nossenko in 1906, and, after the premiere of The Firebird in 1910, he brought her and their two children to France. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 seriously disrupted the Ballets Russes’s activities in western Europe, however, and Stravinsky found he could no longer rely on that company as a regular outlet for his new compositions. The war also effectively marooned him in Switzerland, where he and his family had regularly spent their winters, and it was there that they spent most of the war. The Russian Revolution of October 1917 finally extinguished any hope Stravinsky may have had of returning to his native land.

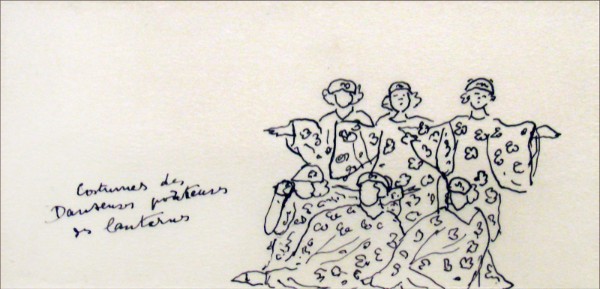

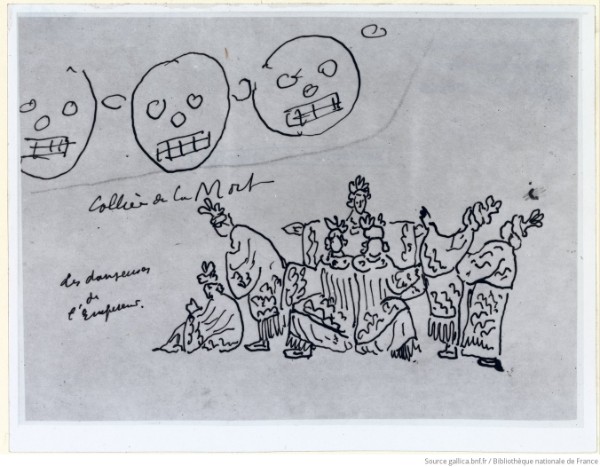

By 1914 Stravinsky was exploring a more restrained and austere, though no less vibrantly rhythmic kind of musical composition. His musical production in the following years is dominated by sets of short instrumental and vocal pieces that are based variously on Russian folk texts and idioms and on ragtime and other style models from Western popular or dance music. He expanded some of these experiments into large-scale theatre pieces. The Wedding, a ballet cantata begun by Stravinsky in 1914 but completed only in 1923 after years of uncertainty over its instrumentation, is based on the texts of Russian village wedding songs. The “farmyard burlesque” Renard (1916) is similarly based on Russian folk idioms, while The Soldier’s Tale (1918), a mixed-media piece using speech, mime, and dance accompanied by a seven-piece band, eclectically incorporates ragtime, tango, and other modern musical idioms in a series of highly infectious instrumental movements. After World War I the Russian style in Stravinsky’s music began to fade, but not before it had produced another masterpiece in the Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920).

The compositions of Stravinsky’s first maturity—from The Rite of Spring in 1913 to the Symphonies of Wind Instruments in 1920—make use of a modal idiom based on Russian sources and are characterized by a highly sophisticated feeling for irregular metres and syncopation and by brilliant orchestral mastery. But his voluntary exile from Russia prompted him to reconsider his aesthetic stance, and the result was an important change in his music—he abandoned the Russian features of his early style and instead adopted a Neoclassical idiom. Stravinsky’s Neoclassical works of the next 30 years usually take some point of reference in past European music—a particular composer’s work or the Baroque or some other historical style—as a starting point for a highly personal and unorthodox treatment that nevertheless seems to depend for its full effect on the listener’s experience of the historical model from which Stravinsky borrowed.

The Stravinskys left Switzerland in 1920 and lived in France until 1939, and Stravinsky spent much of this time in Paris. (He took French citizenship in 1934.) Having lost his property in Russia during the revolution, Stravinsky was compelled to earn his living as a performer, and many of the works he composed during the 1920s and ’30s were written for his own use as a concert pianist and conductor. His instrumental works of the early 1920s include the Octet for Wind Instruments (1923), Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1924), Piano Sonata (1924), and the Serenade in A for piano (1925). These pieces combine a Neoclassical approach to style with what seems a self-conscious severity of line and texture. Though the dry urbanity of this approach is softened in such later instrumental pieces as the Violin Concerto in D Major (1931), Concerto for Two Solo Pianos (1932–35), and the Concerto in E-flat (or Dumbarton Oaks concerto) for 16 wind instruments (1938), a certain cool detachment persists.

In 1926 Stravinsky experienced a religious conversion that had a notable effect on his stage and vocal music. A religious strain can be detected in such major works as the operatic oratorio Oedipus Rex (1927), which uses a libretto in Latin, and the cantata Symphony of Psalms (1930), an overtly sacred work that is based on biblical texts. Religious feeling is also evident in the ballets Apollon musagète (1928) and in Persephone (1934). The Russian element in Stravinsky’s music occasionally reemerged during this period: the ballet The Fairy’s Kiss (1928) is based on music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and the Symphony of Psalms has some of the antique austerity of Russian Orthodox chant, despite its Latin text.

In the years following World War I, Stravinsky’s ties with Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes had been renewed, but on a much looser basis, and the only new ballet Diaghilev commissioned from Stravinsky was Pulcinella (1920). Apollon musagète, Stravinsky’s last ballet to be mounted by Diaghilev, premiered in 1928, a year before Diaghilev’s own death and the dissolution of his ballet company.

In 1936 Stravinsky wrote his autobiography. Like his six later collaborations with Robert Craft, a young American conductor and scholar who worked with him after 1948, this work is factually unreliable. In 1938 Stravinsky’s oldest daughter died of tuberculosis, and the deaths of his wife and mother followed in 1939, just months before World War II broke out. Early in 1940 he married Vera de Bosset, whom he had known for many years. In autumn 1939 Stravinsky had visited the United States to deliver the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard University (later published as the The Poetics of Music, 1942), and in 1940 he and his new wife settled permanently in Hollywood, California. They became U.S. citizens in 1945.

During the years of World War II, Stravinsky composed two important symphonic works, the Symphony in C (1938–40) and the Symphony in Three Movements (1942–45). The Symphony in C represents a summation of Neoclassical principles in symphonic form, while the Symphony in Three Movements successfully combines the essential features of the concerto with the symphony. From 1948 to 1951 Stravinsky worked on his only full-length opera, The Rake’s Progress, a Neoclassical work (with a libretto by W.H. Auden and the American writer Chester Kallman) based on a series of moralistic engravings by the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth. The Rake’s Progress is a mock-serious pastiche of late 18th-century grand opera but is nevertheless typically Stravinskyan in its brilliance, wit, and refinement.

The success of these late works masked a creative crisis in Stravinsky’s music, and his resolution of this crisis was to produce a remarkable body of late compositions. After World War II a new musical avant-garde had emerged in Europe that rejected Neoclassicism and instead claimed allegiance to the serial, or 12-tone, compositional techniques of the Viennese composers Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and especially Anton von Webern. (Serial music is based on the repetition of a series of tones in an arbitrary but fixed pattern without regard for traditional tonality.) According to Craft, who entered Stravinsky’s household in 1948 and remained his intimate associate until the composer’s death, the realization that he was regarded as a spent force threw Stravinsky into a major creative depression, from which he emerged, with Craft’s help, into a phase of serial composition in his own intensely personal manner. A series of cautiously experimental works (the Cantata, the Septet, In Memoriam Dylan Thomas) was followed by a pair of hybrid masterpieces, the ballet Agon (completed 1957) and the choral work Canticum Sacrum (1955), that are only intermittently serial. These in turn led to the choral work Threni (1958), a setting of the biblical Lamentations of Jeremiah in which a strict 12-tone method of composition is applied to chantlike material whose underlying character recalls that of such earlier choral works as The Wedding and the Symphony of Psalms. In his Movements for piano and orchestra (1959) and his orchestral Variations (1964), Stravinsky refined his manner still further, pursuing a variety of arcane serial techniques to support a music of increasing density and economy and possessing a brittle, diamantine brilliance. Stravinsky’s serial works are generally much briefer than his tonal works but have a denser musical content.

Though always in mediocre health (he suffered a stroke in 1956), Stravinsky continued full-scale creative work until 1966. His last major work, Requiem Canticles (1966), is a profoundly moving adaptation of modern serial techniques to a personal imaginative vision that was deeply rooted in his Russian past. This piece is an amazing tribute to the creative vitality of a composer then in his middle 80s.

Like that of so many masters, Stravinsky’s fame rests on only a few works and one or two of his more important achievements. In The Rite of Spring he presented a new concept of music involving constantly changing rhythms and metric imbalances, a brilliantly original orchestration, and drastically dissonant harmonies that have resonated throughout the 20th century. Later Stravinsky was regarded as the typical rootless exile, a creative chameleon who could dart from style to style but who never recaptured the creative depth of his first masterpieces. Yet the more spectacular modernisms of The Rite of Spring belong to the evolution of Russian nationalist music from Modest Mussorgsky to Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, while that work’s feeling of “primitive dynamism” is a period feature that is found in much music of the early 20th century. Nor were the discordant harmonies of The Rite of Spring entirely new in 1913, though Stravinsky was the first to pursue Claude Debussy’s purely sensual approach to chords into a harmony that was not itself obviously beautiful.

The percussive violence and barbaric tone colours of The Rite of Spring did, however, conceal a new kind of rhythmic sensibility and an empirical attitude to sonority that can be traced through all of Stravinsky’s later music, whatever its apparent stylistic allegiance. Stravinsky’s approach was empirical in that he was not prepared to accept established musical practice about development but instead preferred to subject his musical material to a personal system of tests. Working always at the piano, he experimented endlessly with different chord combinations and spacings, explored asymmetrical metrical patterns, and used devices of prolongation and elision to break down the tradition of symmetrical phrasing. Given such sonorities as basic sound objects, rhythm is then regarded as a cumulative process, an adding together of such objects into varied groups, as opposed to the varied subdivision of regular groups that forms the basic method of classical music. Not surprisingly, this procedure tended to work against the past musical styles that Stravinsky used as models in his Neoclassical works, which probably accounts for their intriguing rhythmic obliquity, just as his experimental attitude to chords produced curious distortions of classical harmony. Stravinsky worked in the same way, in fact, throughout his life, and the same basic principles of construction and dynamics inform Threni and the Requiem Canticles as Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. He had immense influence on the way later composers have felt pulse, rhythm, and form.

Stravinsky rejected the Germanic idea that thematic development is the only basis of serious writing. From early on, he preferred a sculptural approach in which the sound object is all-important and large musical structures are achieved cumulatively, with much repetition allied to subtle variations in interior detailing. In his longer works, especially the sacred and theatrical ones, this tends toward an effect of ritual. The power of Oedipus Rex and the Symphony of Psalms, as of The Rite of Spring, is the power of a solemn reenactment, and it was in his sense of the motion and specific gravity of such solemnities that Stravinsky was at his most forceful and inspired.