by

French conductor Pierre Monteux (1875–1964) always seemed to be the right man at the right time. As a student of violin and viola at the Paris Conservatoire, his fellow students included George Enescu, Fritz Kreisler, and Alfred Cortot. Upon graduation, one of his first jobs was violist for the orchestra of the Folies Bergère (1889–1892), when the Folies had Toulouse-Lautrec doing their posters. He played in or conducted works by Camille Saint-SaënsSaint, including being a last-minute conductor for a performance of Saint-Saëns’s cantata La Lyre et la Harpe (the composer at the organ), earning Saint-Saëns’s undying gratitude.

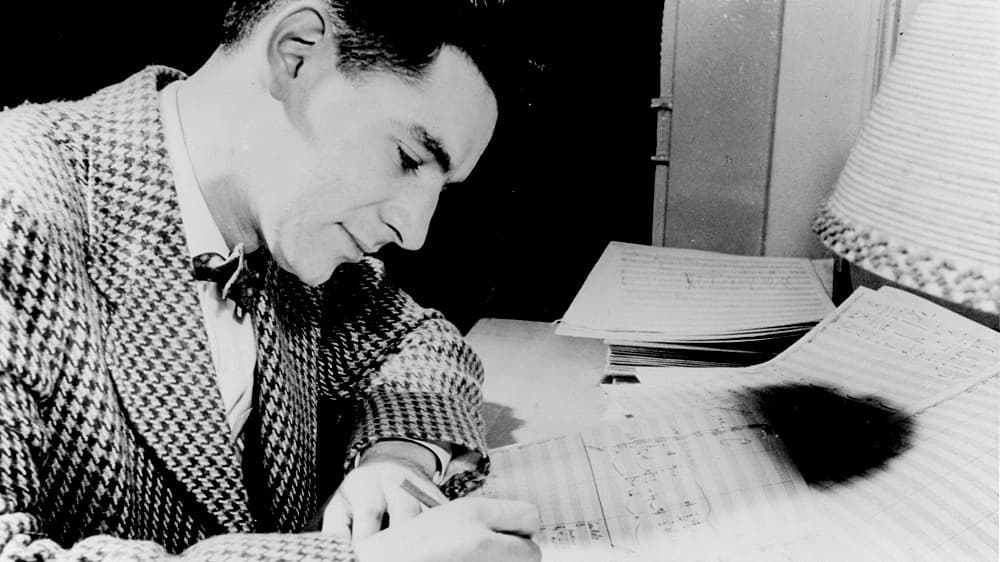

Irwin D. Hoffmann: Pierre Monteux, 1959 (Boston Public Library)

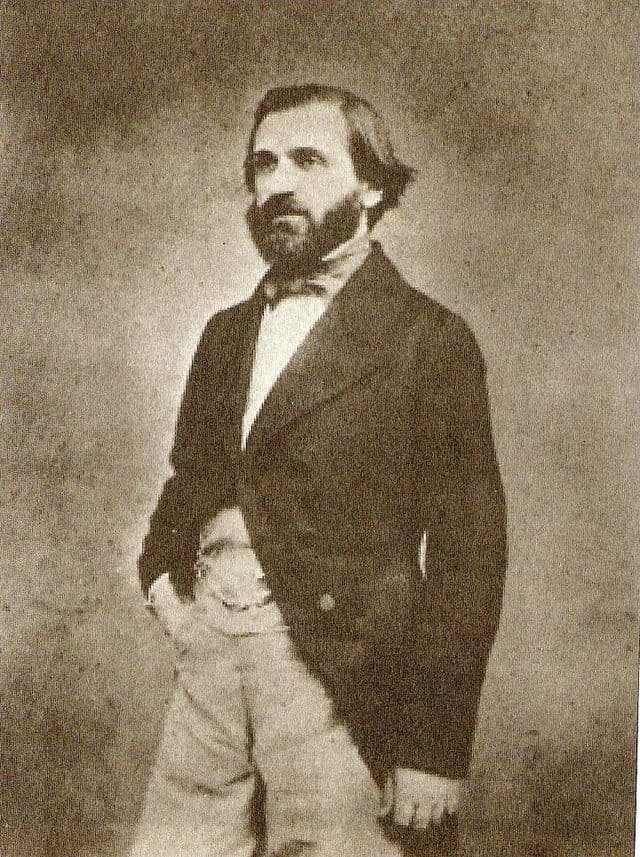

In 1894, he was named both principal violist and assistant conductor of the Colonne Orchestra in Paris. The orchestra’s founder, Édouard Colonne, had known Berlioz and could work with Monteux on what the composer really wanted in a performance of his works. His next position was as chief conductor for the seasonal Dieppe Casino orchestra (while still maintaining his Colonne positions).

In 1910, the Colonne Orchestra played for the Ballets Russes season, and Monteux met Stravinsky for the first time. He played viola for the world premiere of The Firebird in 1910, and the next year led the rehearsals for the premiere of Petrushka. He ended up conducting the premiere as well, at the insistence of the composer.

Along with impressing Saint-Saëns and Stravinsky, he also caught the eye of Claude Debussy, particularly because of his ability to rehearse and present new music. When the Colonne Orchestra was giving the world premiere of Debussy’s Images pour orchestra, it was Monteux who led the orchestral rehearsals, and Debussy conducted the premiere (26 January 1913).

After the January premiere of Images, it was onto Debussy’s ballet Jeux and then, on 29 May 1913, the infamous premiere of The Rite of Spring and riot.

With the start of WWI, Monteux was conscripted into the French Army, but Diaghilev got him released to take the Ballets Russes on tour to North America. After the war, the Boston Symphony Orchestra approached Monteux to be their new chief conductor. He only lasted 5 years there, but changed the orchestra for the better, and handed it over to Serge Koussevitzky, who would be its music director for the next 25 years.

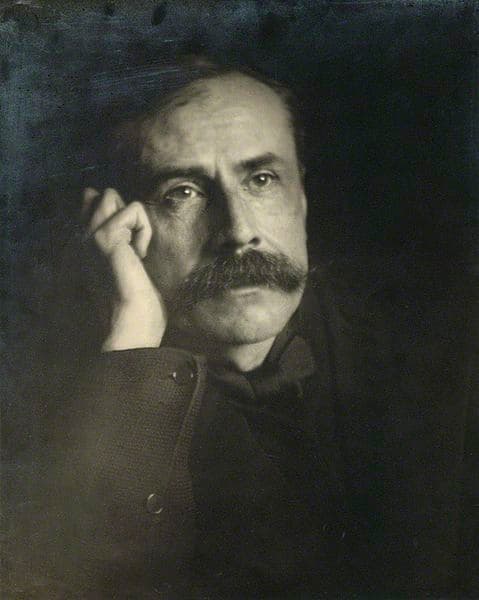

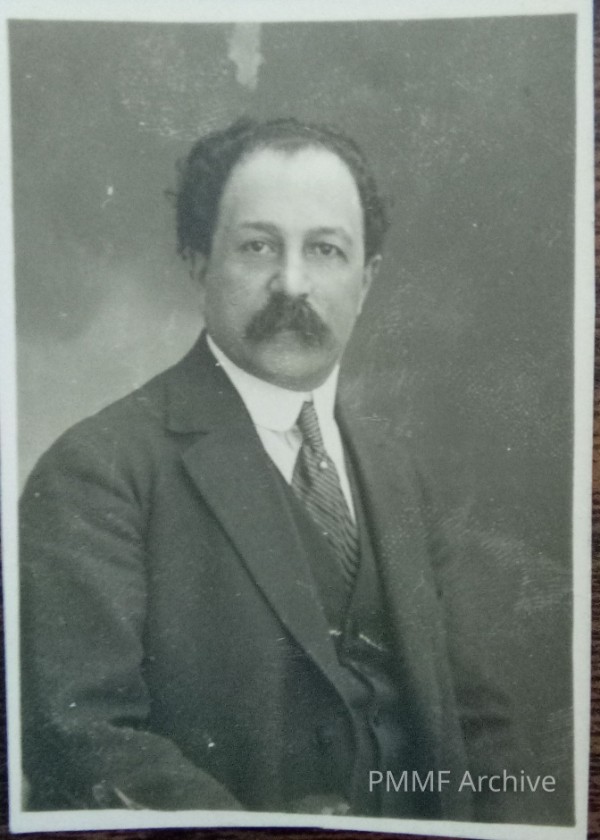

Pierre Monteux, 1924 (Pierre Monteux Memorial Foundation Archive)

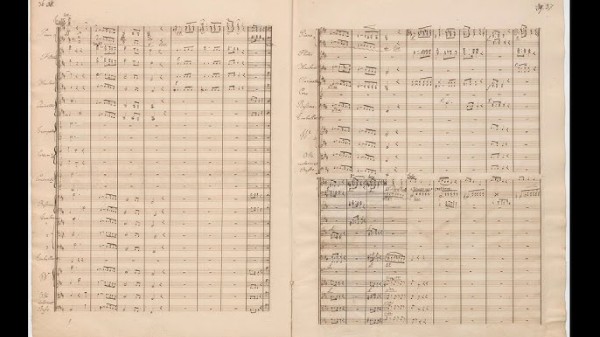

Monteux, in the meantime, went to Amsterdam, where he became the first conductor at the Concertgebouw, serving under Willem Mengelberg, the chief conductor. The other major work on this new recording is Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, written in 1931 for the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The influence of Bach on Stravinsky is palpable in the Symphony, particularly Bach’s St Matthew Passion, which had been widely played all over Europe during the work’s bicentenary in 1927.

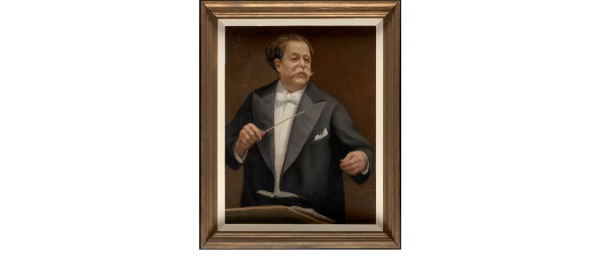

Alfred Bendiner: Pierre Monteux (1947) (Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, Gift of Mrs. Alfred Bendiner)

Taking up his conducting career at the cusp of the 20th century, Monteux took part in some of the most exciting and controversial happenings in music, from premieres of works by Saint-Saëns to the Parisian riots over Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. He brought the Boston Symphony back to life and then went on to lead one of Europe’s great orchestras.

This 150th anniversary tribute to Pierre Monteux was recorded in 1961 as a live broadcast on the BBC Home Service. The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, as led by Monteux, give us the best of his repertoire in performances of works that couldn’t be further apart in style: Debussy’s orchestral Images, and Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms.

Pierre Monteux: 150th Anniversary Tribute: Live Performances

BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

SOMM Recordings ARIADNE 5042

Official Website