by

César Franck’s genius flowered astonishingly late. Until his 50s, he composed mostly sacred choral works, songs, and early orchestral essays that met with indifference. Public acclaim eluded him as even his 1841 Trio dedicated to Franz Liszt faded quickly.

César Franck

Yet from 1879 onward, a creative surge produced masterpieces that redefined French music. Just think of the passionate Piano Quintet, the vivid symphonic poem Le Chasseur maudit, the Symphonic Variations or the Prélude, Choral et Fugue.

César Franck: Prélude, Choral et Fugue

Disowning his Youth

These works fused German structural depth with elegance, influencing Ravel, Debussy, and the entire École Franckiste. Yet, Franck remained a modest man, dying on 8 November 1890 after a street accident exacerbated pleurisy.

In his early years, however, Franck displayed an astonishing natural gift for the piano and composition. He was one of the most astonishing child prodigies ever, giving public concerts of dazzling difficulty, improvising with effortless invention, and composing works that revealed a striking command of harmony and form.

Franck assigned opus numbers to his juvenile works, but later in life, disowned them. To commemorate his passing on 8 November, why don’t we listen to some of these rejected gems of Franck’s early precocity.

Child Genius

César Franck

Just imagine a twelve-year-old boy stepping onto a candle-lit stage in Liège, in 1834. César Franck launches into his own Premier Grand Concerto, Op. 2, with octaves thundering and themes pirouetting like circus acrobats.

The king sends him a gold medal, and critics hail him as “a second Mozart!” Yet the boy at the keyboard was already bored. He has just finished writing his second piano concerto before breakfast.

Relentlessly exploited by his father and reduced to a traveling cash register, Franck’s childhood was anything but ideal. Nicolas-Joseph Franck, a failed painter turned banker, saw in his elder son the jackpot every stage parent dreams of.

By eight, César was enrolled at the Liège Conservatory, sweeping medals in piano, harmony, and sight-singing. By eleven he gave his first public recital. By twelve he was on the road to Brussels and Antwerp billed as “The Prodigy Franck.”

César Arrives in Paris

Franz Liszt and Sigismond Thalberg

Predictably, it was time to look towards Paris, a city that in the 1830s was a circus of virtuosos. Liszt made pianos weep and Thalberg made them sparkle. Into this dazzling arena Nicolas-Joseph Franck dragged his sons, renting cramped rooms in the bohemian ninth arrondissement.

César, thirteen, played for Anton Reicha, Beethoven’s friend, and the Conservatoire’s gatekeeper of genius. The boy sight-read a Bach fugue, then improvised another, yet the doors of the Conservatoire remained closed as foreigners could not be admitted.

Nicolas-Joseph, undeterred, secured French citizenship papers with remarkable speed, and on 4 October 1837, the fifteen-year-old César Franck strode through the gates as a newly minted Frenchman.

Quiet Conquest

César Franck

What followed was five years of quiet conquest. One by one, the Conservatoire’s highest honours fell before him. 1er Prix de Piano (1838, age fifteen), 1er Prix de Contrepoint (1839), 1er Prix de Fugue (1840, age seventeen), 2ème Prix d’Orgue (1841), and the Grand Prix d’Honneur for transposing a fiendish sonata down a minor third at sight.

When examiners challenged him to improvise a fugue on a theme by Cherubini, he produced a double fugue so brilliant that the aging composer himself, seated in the audience, was speechless.

Another wonderful anecdote survives. In 1838, examiners asked the boy to harmonize a plainchant on the spot. He delivered four versions, with harmonies by Bach, Palestrina, Beethoven, and himself.

The Cash-Cow Variations

Between 1834 and 1837, César Franck produced twenty publishable piano works, gave each an opus number, and watched his father turn them into cash. These pieces in the brilliant style sound like a time capsule of 1830s Paris.

We find the cash cow of the decade in his “Variations brillantes.” Take a hit tune, spin six variations, and finish with a polonaise. Here, young Franck was guided by models of Herz, Hünten, and the young Thalberg.

We also find free-form roller-coasters in his “Grandes Fantaisies.” Generally, it starts with a slow introduction, followed by a borrowed tune that gets dramatically developed, all finishing with a flashy coda. This is the stuff that made Franz Liszt famous.

Two Concertos, One Bonfire

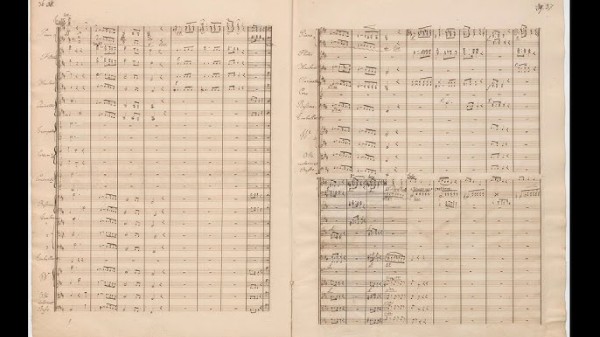

César Franck’s Piano Concerto No. 2

Two full-scale concertos crowned the early Franck catalogue. The first, premiered when César was twelve, vanished into his own fireplace a decade later. Not a single page survived the adult composer’s wrath.

A single sentence in Robert Stove’s biography explains the purge. “Franck personally destroyed the manuscript of his First Concerto, determined that no trace of his father’s greed should embarrass his adult reputation.”

The second, a twenty-five-minute B-minor juggernaut of pure teenage thunder miraculously escaped the flames. It was printed in 1836, but the score lay forgotten until it was dusted off in 1984.

The Exile that Forged a New Composer

In 1842, Nicolas-Joseph Franck stormed out of Paris with his family in tow. The press had turned savage, and Henri Blanchard, chief critic of the Revue et Gazette musicale, mocked the father’s “imperial” names for his sons and called the endless family concerts “aggressive commerce.”

One review actually ended with the line “Enough of the Francks!” Nicolas-Joseph yanked César from the Conservatoire mid-semester and brought the family back to Belgium for a fresh virtuoso tour.

Thankfully, the excursion only lasted eighteen months, and by the spring of 1844, the family was back in Paris. However, César had had enough. He had fallen in love with his piano student Félicité Desmousseaux, an actress from a “scandalous” theatre family.

Two years later, César walked out for good and married Félicité amid revolution barricades. He never spoke to his father again, and the break freed him from the virtuoso circus. That’s when the cathedral composer was born.

Inventing Tomorrow

César Franck at the organ

Of the twenty glittering receipts his father forced into print, only one escaped the adult Franck’s censure, the Première Grande Fantaisie, Op. 12. He played it in recitals as late as the 1880s.

Why should this have been the lone survivor? It’s rather obvious, really, because beneath the Hummel octaves and Chopin-scented trills, the fourteen-year-old boy had already invented tomorrow.

In measure 27, a four-note motif rises in the left hand, is answered by the right, and then vanishes into a storm of arpeggios. 200 measures later, it returns in the coda, now transfigured, radiant, and binding the whole fantasy together.

The young boy had discovered cyclic form, and he never let it go. That technique and trademark would later bind the D-minor Symphony and loop the Prélude, Choral et Fugue. In fact, every late masterpiece was born between a trill and a polonaise.