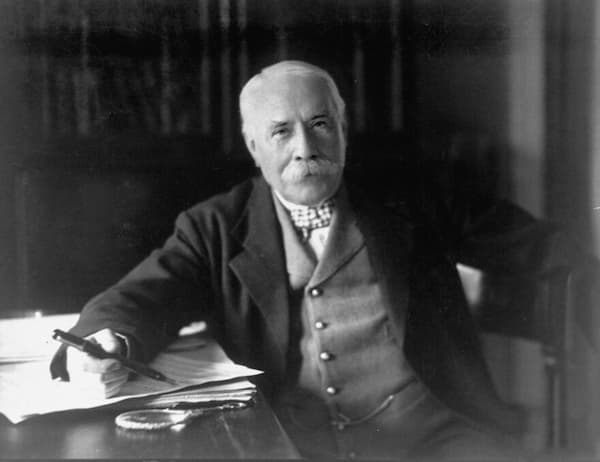

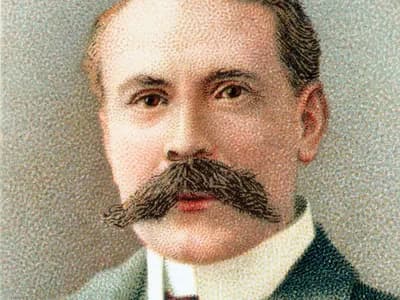

As a musician and composer, Edward Elgar was largely self-taught, learning through experimentation and playing in local ensembles. His music is characterised by its emotional depth, rich orchestration, and a sense of nostalgia that captures a time when the British Empire was at a peak.

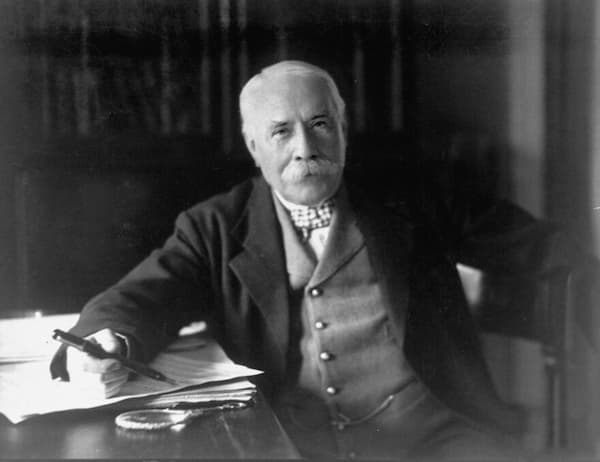

Edward Elgar

During his later years, a period of personal struggles and the changing musical landscape, Elgar’s music endured by evoking a sense of pride and the pastoral beauty of England. Blending English elements with a personal, sometimes melancholic style, Elgar left behind a legacy that continues to resonate with audiences around the world.

Edward Elgar was reserved and private in his personal life, and he often felt like an outsider in the social circles of the time. While he did engage with the public through his music, Elgar was not known for making bold or controversial public statements. Later in life, Elgar became even more withdrawn and moved to a quieter part of England where he could continue composing in relative solitude.

On the occasion of Elgar’s passing on 23 February, let us offer some insight into his personality by exploring 10 of his most famous quotes and general thoughts.

Edward Elgar: Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 “Land of Hope and Glory”

“I always said God was against art, and I still believe it”

Attributed to Elgar, this quote is not tied to a specific documented event or piece of correspondence, and it might have been said in private conversation or during a moment of reflection. To be sure, Elgar’s statements often carried a tone of introspection or philosophical musing about the nature of art and life.

In this case, however, we get a clue from the second part of this quote when Elgar said, “Anything obscene or trivial is blessed in this world and has a reward, I ask for no reward, only to hear my work.”

Elgar had a complex relationship with his own creativity, experiencing periods of great success but also times of deep personal and creative depression. And during his early career, Elgar faced great challenges in getting his music recognised. He certainly believed that the divine forces were not necessarily on the side of the artist.

Edward Elgar: Salut d‘Amour, Op. 12

“The music is in the air. Take as much as you want.”

This particular quote encapsulates Elgar’s philosophy on creativity, music, and its omnipresence. Throughout his life, Elgar spoke about music as something that was not just created but discovered or captured from the environment around him.

Edward Elgar

Elgar implies that there is no limit to the inspiration one can draw from the world. It is a democratic view of the arts, where inspiration is not in the exclusive domain of the professional composer but available to all.

It aligns with the ideas of the Romantic movement and its emphasis on emotion, nature, and the individual’s experience. In Elgar’s mystical view of creativity, music does not need to be laboriously contracted but exists all around us. It’s simply an invitation for everyone to engage with music. In a sense, it also expresses Elgar’s idea about the universal nature of music and its ability to transcend cultural and linguistic barriers.

Edward Elgar: Sea Pictures

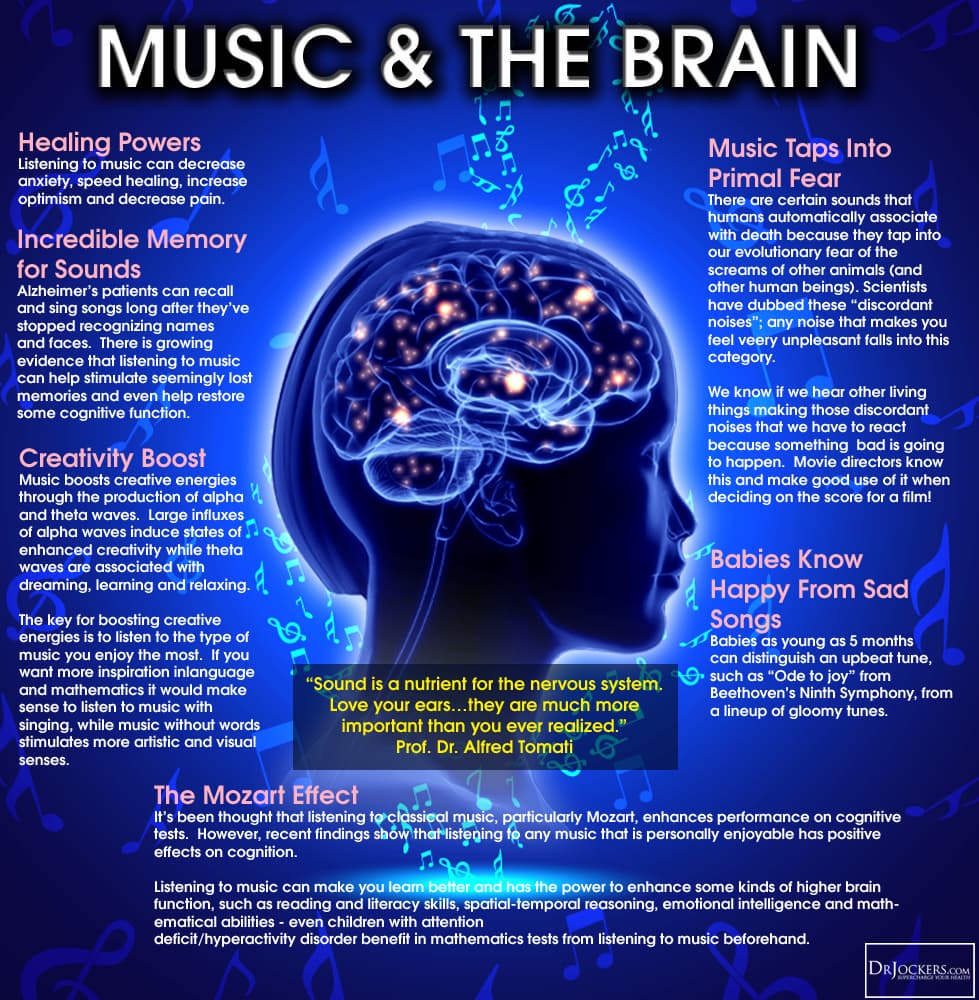

“I believe in the power of music to bring people together, to heal, and to inspire.”

Not directly attributed to Edward Elgar, the above statement does encapsulate sentiments that align with Elgar’s known views on the role of music and society and personal life. Elgar expressed his strong belief about the communal and therapeutic aspects of music throughout his life.

Elgar lived through turbulent times in history, and his music was often seen as a means to foster national identity. His saying possibly reflects his understanding of music’s role in bringing people together during times of national crisis and war.

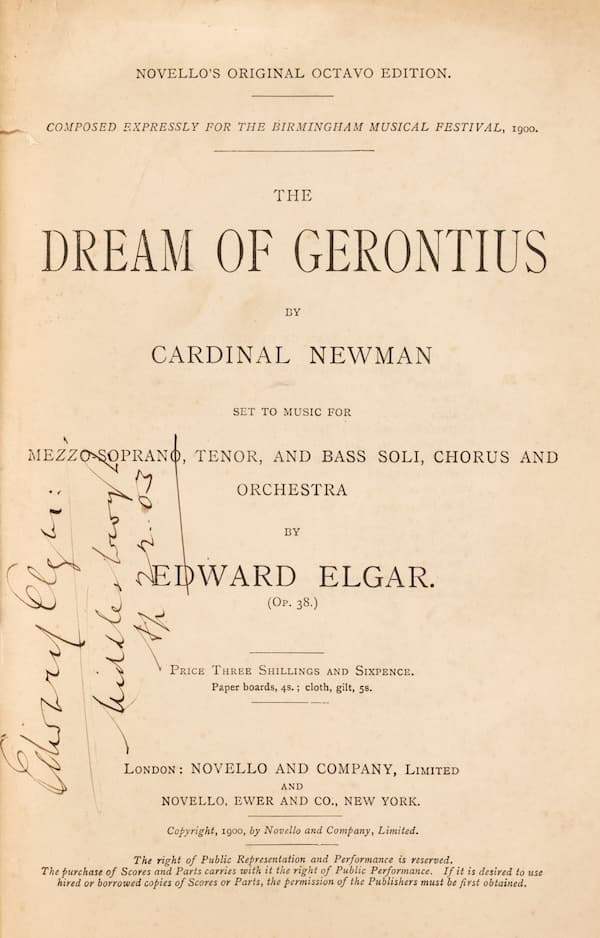

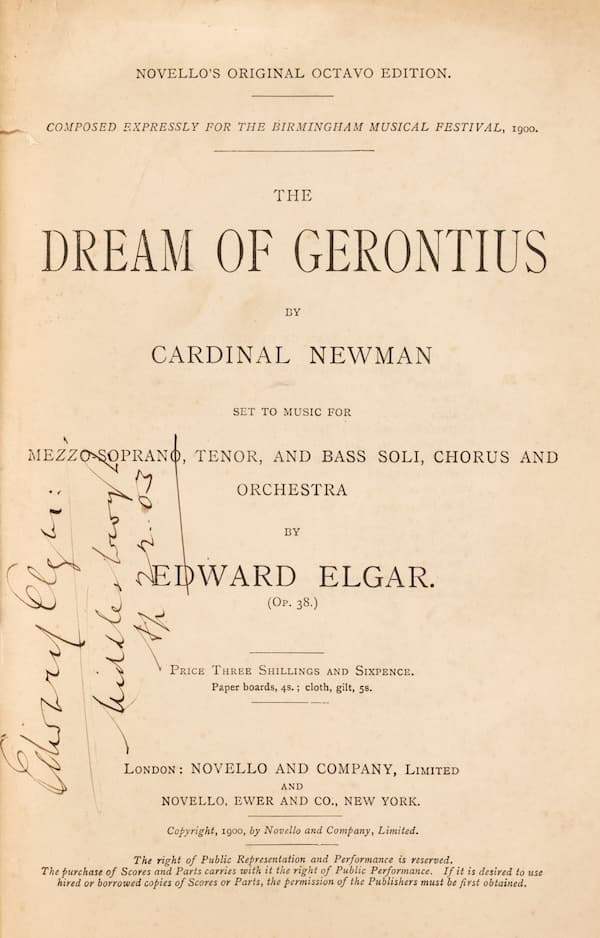

Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius

Music therapy had not yet been a formalised practice during Elgar’s time, but the therapeutic qualities of music were something Elgar might well have appreciated personally, especially considering his bouts with melancholy. To be sure, the idea that music can soothe the soul or help with emotional recovery would have strongly resonated with him.

Edward Elgar: The Dream of Gerontius (excerpt)

“Music has the power to express the deepest emotions when worlds are insufficient.”

Elgar was known for his introspective nature, and he certainly felt that music was his most effective means of communication. That was particularly true for complex or deep emotions that he found difficult to articulate in words.

For Elgar, music had the ability to transcend the limitations of verbal language. When words fail to capture the nuances of emotion, music can step in to express what is felt but not easily said. As such, music does not simply function as surface-level communication but reaches into the depths of human experience.

Elgar also seems to acknowledge music’s universal appeal. The world of emotions is part of the human condition across cultures, and music’s ability to express these emotions can connect people universally.

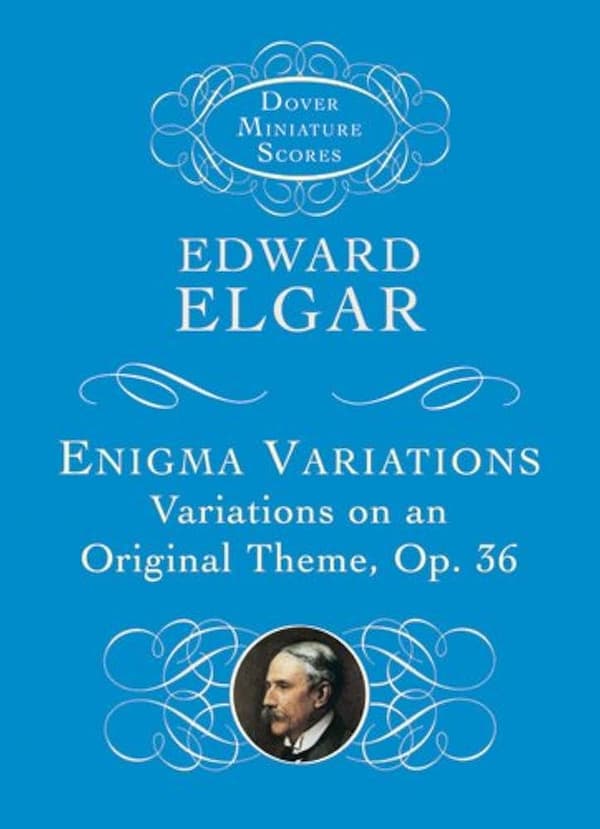

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations

“The object of art is to give life a shape.”

According to Elgar, art reflects the human condition, capturing moments, emotions and concepts that might otherwise be fleeting or inexpressible. For Elgar, art had a higher purpose, offering a lens through which we can view our existence.

For Elgar personally, this quote reflects his own composition process, in which he turned his personal experiences, like his love for his wife Alice or his contemplation of death and afterlife, into musical expressions that shaped his life’s narrative.

While he was speaking from the perspective of a composer, Elgar’s ideas resonated across all art forms. He strongly believed in the transformative power of art, not merely mirroring life but its ability to actively shape our perception, understanding, and experience of it.

Edward Elgar: Symphony No. 1

“Music is like a dream. One that I cannot hear.”

Later in his life, Elgar suffered from hearing loss. His hearing began to deteriorate around the time of World War I, but by the end of his life, his ability to hear was significantly impaired. His personal struggle with hearing loss reflected the irony of a composer who could no longer fully experience his own art.

Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations

As Elgar aged, his composition took on a more reflective and sometimes melancholic tone. Music, which he spent his life creating and his means of expression, was becoming inaccessible to him in its most literal sense.

Elgar often spoke of music in terms that suggested it was something one could feel or sense beyond just hearing. In that sense, it aligns with the idea of music being dreamlike or existing on a plane beyond the physical. This quote, not explicitly attributed to Elgar, tells of the joy of creation juxtaposed with the personal tragedy of losing one’s ability to hear.

“This is what I hear all day, the trees are singing my music. Or have I sung theirs?”

Edward Elgar was born in Worcestershire and lived in and around Malvern and the Malvern Hills for many years. He was routinely seen cycling around the surrounding countryside and village lanes, and the natural landscape inspired many of his well-known compositions.

His music often evokes the pastoral, serene, and melancholic beauty of nature. But Elgar is also musing on the origin of music. Is it his own creation, or is he merely channelling something that already exists in nature?

Elgar seems to suggest that by expressing his intimate experiences with nature, his music is not just a scenic backdrop but an active participant in his creative process. There is a great sense of humility in this quote, as Elgar acknowledges the fact that his music might be part of something larger than his individual self.

“I never thought I was a genius. I knew I was a composer.”

Despite his eventual recognition as one of England’s greatest composers, Elgar’s early career was marked by struggles for recognition. In fact, he did not gain significant acclaim until much later in life, specifically after the premiere of his “Enigma Variations” in 1899.

His ideas of genius are often associated with Romantic idealism, the idea of an artist as someone touched by divine inspiration. Elgar certainly felt that way and accepted a sense of isolation and of being misunderstood.

Despite his achievements, Elgar was known for his humility. He often felt out of place among the more formally educated musicians of his time as he learned his craft through personal study and practice rather than academic training.

Edward Elgar: Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 84

“It is curious to be treated by the old-fashioned people as a criminal because my thoughts and ways are beyond them.”

Elgar’s innovative musical style often clashed with the more conservative tastes of his contemporaries. He lived during a transitional period in history when music was transitioning from the Romantic era into 20th-century modernism. As his work spanned both periods, his music was somewhat of a bridge between the traditional and the new.

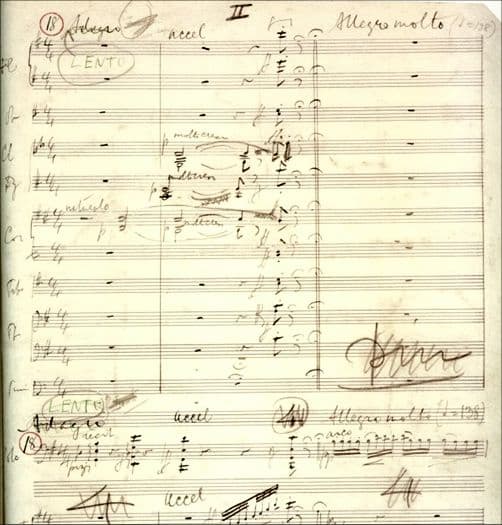

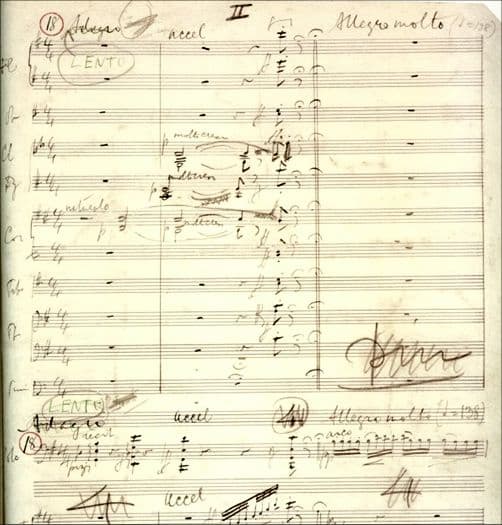

Elgar’s Cello Concerto manuscript

His music was often seen as both traditional in its beauty and innovative in its orchestration and harmonic language. As he was writing during a time when a significant portion of the British musical establishment preferred music that adhered strictly to classical norms, he wasn’t appreciated by those with a more conservative musical palate.

While his music was rooted in tradition, it also pushed boundaries. Elgar’s music, which was controversial in his day, is now celebrated for its originality and depth. Elgar was well aware of the fact that in the evolution of culture, what was once avant-garde can become mainstream over time.

“I have no regrets, except that my music is not better known.”

Primarily known for his orchestral works, and despite significant contributions to music, Elgar long felt that his work did not achieve the universe recognition he believed it deserved. This quote likely stems from a period when Elgar was reflecting on his career, possibly near or after his retirement from active composition.

While his music was celebrated in Britain, it did not enjoy the same level of international fame accorded to his contemporaries Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. Elgar lived a life largely filled with personal satisfaction and acceptance; however, his deep-seated desire for broader recognition of his musical legacy did not come to pass during his lifetime.

While he initially lamented a lack of broader appreciation for his artistic vision, history has somewhat alleviated Elgar’s regret. His compositions are now seen as emblematic of English music, greatly influencing subsequent generations of composers and remaining a significant part of the classical music canon.

Elgar’s music continues to captivate audiences worldwide as an embodiment of English musical identity at a pivotal time. His music is now universally recognised as a testament of his genius, resonating through time and cementing his status as a musical icon whose impact is profound and enduring.