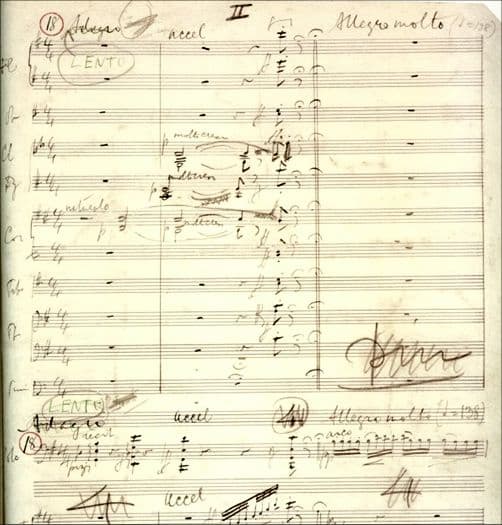

At just 20 years of age, this electrifying performance secured her international reputation almost overnight, transforming her into one of the most celebrated classical artists of the 20th century. That single recording of Elgar’s concerto has remained in print for decades and, for many listeners and musicians, stands as the definitive interpretation of the work.

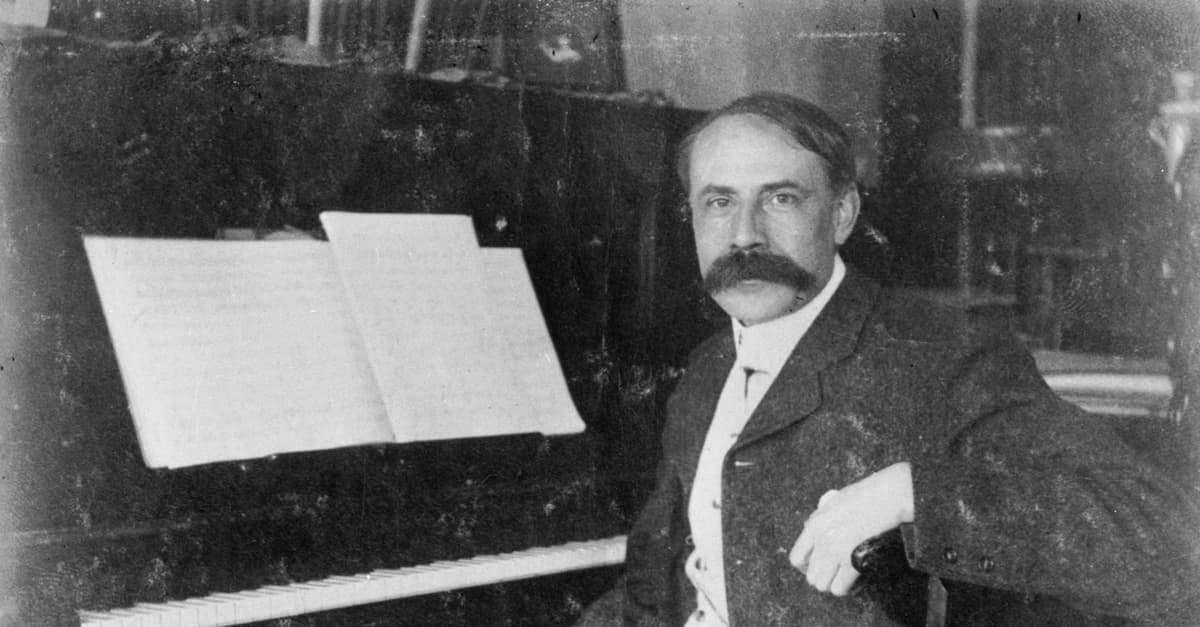

Jacqueline du Pré

But to remember Jacqueline du Pré only for Elgar is to undervalue the breadth of her artistry. Though her career was tragically brief, curtailed by multiple sclerosis in her late twenties, she left behind a rich and varied discography spanning concertos, sonatas, and chamber music.

On the occasion of her birthday on 26 January, let’s explore Jacqueline du Pré’s artistry, which revealed the cello’s immense expressive range through her recordings of Brahms, Beethoven, Schumann, and Haydn.

Breathing Life into Schumann

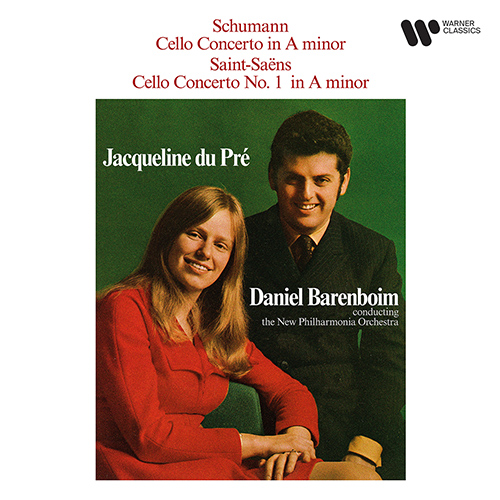

While Elgar remains the work most closely associated with her name, du Pré’s recorded output reveals a musician whose repertoire was both broad and engaging. And it is Robert Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A minor, Op. 129 that perhaps most closely aligns with du Pré’s romantic sensibility after Elgar.

Her recording, made with Daniel Barenboim conducting, captures the concerto’s sustained lyricism and conversational interplay between soloist and orchestra. Where some cellists approach Schumann with restrained elegance, du Pré brings a strong sense of emotional urgency.

Du Pré shapes phrases with a directness that turns inward moments of reflection and outward gestures of intensity into a single, continuous narrative. This approach gives the concerto a strong sense of forward momentum, making its episodic structure feel unified and purposeful rather than fragmented.

At the time, the concerto was still less frequently performed and recorded than it is today, and du Pré’s interpretation played a role in renewing interest in the work. It helped establish the concerto as a central part of the Romantic cello repertoire rather than a peripheral curiosity.

Narrative and Nuance in Dvořák

Jacqueline du Pré © Alamy

One of the greatest concertos in the repertoire, Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, is rich in folk-like pathos and expansive thematic writing. And to be sure, du Pré’s recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Barenboim is another cornerstone of her discography.

Critics at the time and since have pointed to her warm, full-bodied tone, wide dynamic range, and instinctive grasp of the concerto’s large-scale structure. Rather than treating the work as a series of contrasting episodes, du Pré shapes it as a coherent narrative, allowing moments of lyric intimacy and heroic projection to grow naturally out of one another.

The result is a performance that many listeners and commentators continue to regard as both emotionally satisfying and artistically authoritative.

Recordings and filmed performances of this concerto still attract millions of listeners online, a testament not only to the enduring appeal of Dvořák’s music but also to du Pré’s ability to communicate it with uncommon immediacy and conviction.

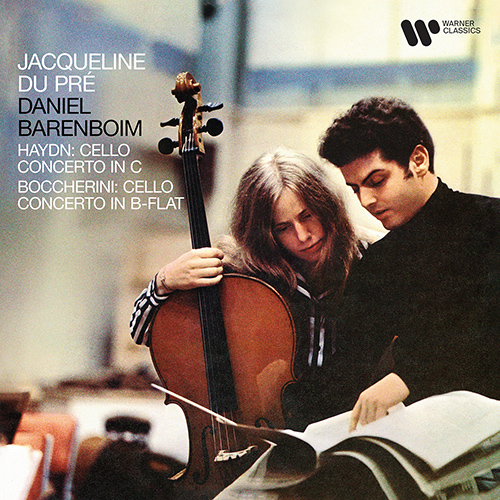

Smiling Vitality in Haydn

Du Pré’s concerto recordings were not limited to the core Romantic repertoire. Her performances of Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major demonstrate her capacity for joyful, elegant playing in the Classical era, where clarity of line and rhythmic buoyancy are paramount.

Rather than imposing Romantic weight on the music, du Pré brings a lightness of articulation and a natural sense of forward motion that allow Haydn’s wit and formal elegance to emerge clearly. Critics have often noted this stylistic flexibility.

Reviewing her Haydn performances, one commentator remarked that du Pré played with “a smiling vitality and unfussy grace,” showing that her musical personality was not limited to intensity alone.

Another described her approach as “fresh, buoyant, and direct,” praising the way she combined technical precision with an unaffected sense of joy. Du Pré herself resisted being typecast as a purely passionate or impulsive performer, and her Haydn recordings beautifully support this view.

Dialogue and Balance in Beethoven

Du Pré was not only a concerto soloist. She was also a consummate chamber musician and interpreter of intimate works. Her collaborations with pianist Daniel Barenboim, her husband from 1967, produced some of her most sensitive and revealing recordings.

In the realm of chamber music, du Pré’s recordings of Beethoven’s Piano Trios, Op. 70 Nos. 1 and 2, made with Daniel Barenboim and violinist Pinchas Zukerman, reveal an important side of her musicianship. Freed from the heroic projection demanded by concerto repertoire, du Pré demonstrates an instinctive understanding of balance, proportion, and musical conversation.

Her cello line is never dominant for its own sake. Instead, it is woven into the ensemble texture with a natural responsiveness that allows Beethoven’s contrapuntal writing to speak clearly.

Contemporary critics frequently remarked on the sense of equality among the players. One reviewer described the trio as performing with “the alertness of three soloists listening intently to one another,” noting that du Pré’s phrasing seemed shaped as much by what she heard from her colleagues as by her own musical impulses.

Intimate Conversations with Brahms

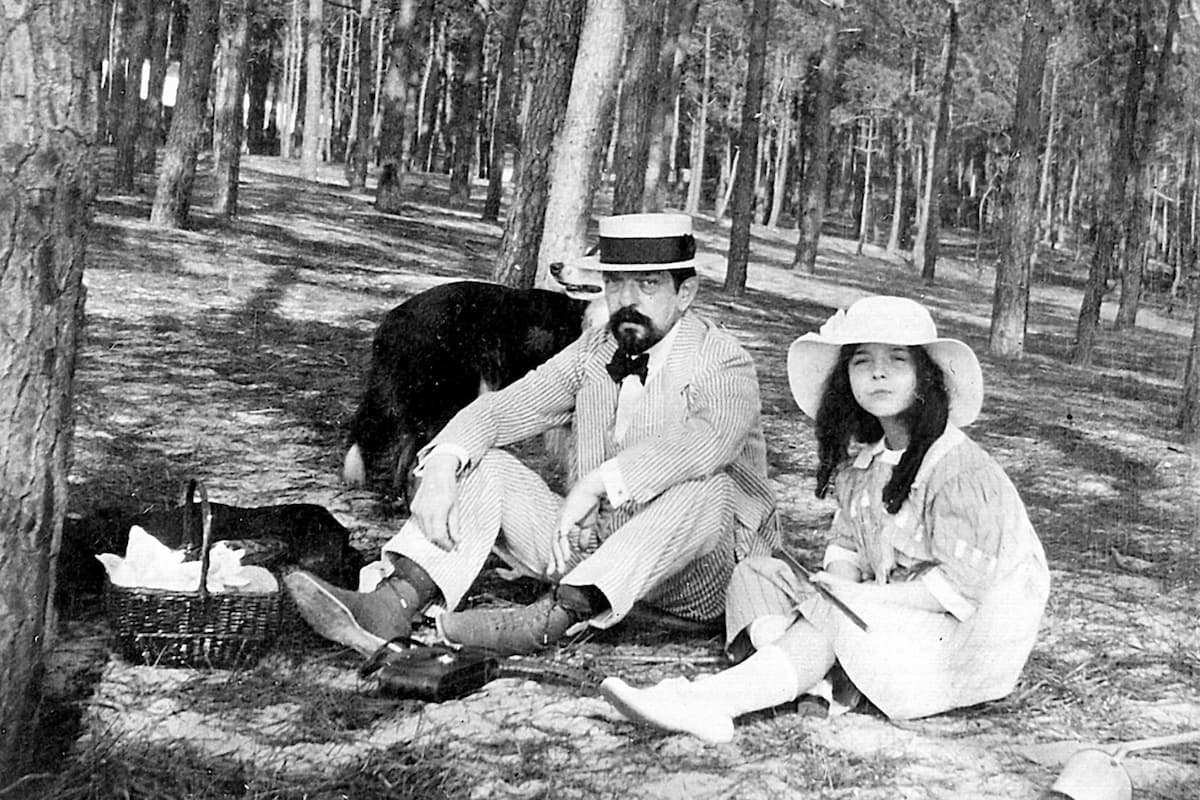

Jacqueline du Pré and Daniel Barenboim

The cello sonatas of Johannes Brahms reveal another layer of du Pré’s artistry. With Barenboim at the piano, these recordings are celebrated for their tenderness and depth by casting Brahms’ rich harmonic writing in a beautifully introspective light.

Her ability to shape phrases with both power and subtlety made these sonatas stand out as profound musical conversations, highlighting du Pré’s emotional range and artistic maturity.

From the mellow lyricism of Brahms to the fiery dialogue of Beethoven, and from the introspective sorrow of Schumann to joyous and agile Haydn, Jacqueline du Pré’s recordings are more than technical achievements. They are testimonials for an intensely felt musical life lived with passion and authenticity.

Though her career was brief, the emotional power, technical brilliance and spirited communication of her playing ensure that Jacqueline du Pré remains not just a historical figure, but a living presence in the classical music world.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.