by Hermione Lai, Interlude

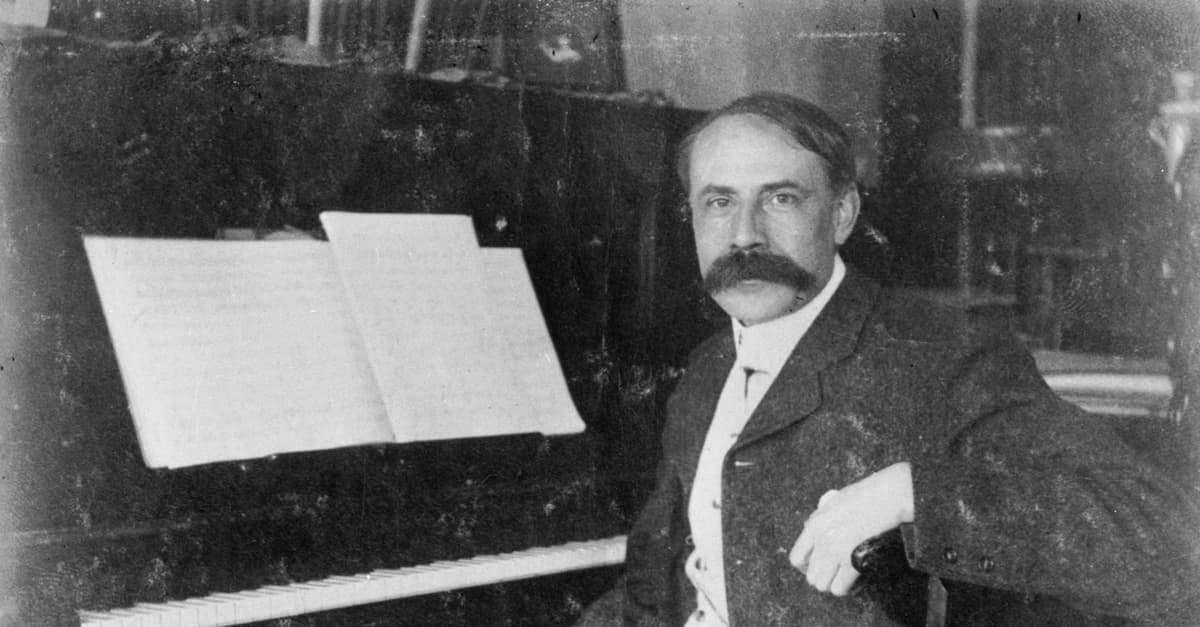

Edward Elgar

On the other hand, Elgar made his money from lighter and less significant works. He certainly received a steady income from royalties on short pieces composed for publication and sale in the form of sheet music for the home market. And not surprisingly, the most common instrument for home entertainment was for the upright piano. But before we get into the solo piano pieces, here is a delightful Romance for piano and violin, published as Elgar’s Op. 1.

The majority of Elgar’s compositions for solo piano stem from the early part of his career, or the very end of his life. As a child, Elgar was praised for his piano improvisations, but he claimed “that playing the piano gave him no pleasure.” And while he did take some violin lessons, he was certainly a proficient pianist.

Edward Elgar: Chantant

Let’s not get distracted, the majority of Elgar’s works for solo piano were composed specifically with that instrument in mind. Take for example Chantant of 1872, a work written at the age of fifteen in the style of a Mazurka. It features all the rhythmic aspects of that particular dance, with Elgar repeating the principle theme with slight changes of colour. A rather interesting “chorale” serves as a type of interlude with the main theme rushing to a dramatic conclusion.

Edward Elgar: Douce Pensée

A good many of these early pieces were probably composed as musical gifts for friends and relatives. Although similar in style and simply in structure, they all contain a certain gaiety and rhapsodic charm. Just listen to Douce Pensée, composed during a visit to Yorkshire in 1882. Originally, the piece was written as a trio for Elgar, his friend Dr. Buck and his mother.

Elgar met Dr. Charles Buck, a member of the British Medical Association in Worcester in 1882, and that meeting became the start of a life-long friendship. Elgar was invited to Dr. Buck’s house in Giggleswick, Yorkshire, and since the good doctor was a competent amateur cellist and his mother played the piano, Elgar expanded a trio he had started the previous year. He later arranged the trio for solo piano and called it Douce Pensée (Gentle Thought). It eventually also became a piece for violin and piano renamed “Rosemary,” and carried the subtitle “That’s for Remembrance.”

Edward Elgar: Presto

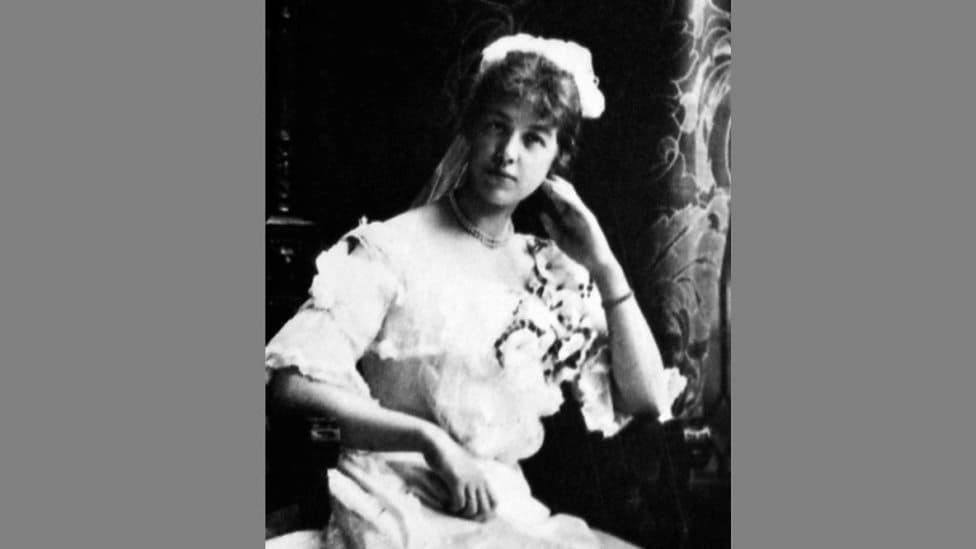

Isabel Fitton

As a birthday present for the twenty-first birthday of Isabel Fitton, Elgar composed a delightful “Presto.” Isabel was the daughter of one of Elgar’s greatest friends, the splendid local pianist Harriet Fitton. Maybe you know that name from another context? Isabel was a viola player, and her name and instrument appears in the sixth Enigma variation dedicated to “Ysobel.” That variation begins with a viola figure that Edward had written for her earlier. The Presto, dating from 1889, however, is all Chopin. After a great opening flourish, we find a short Chopin-like episode, with both sections repeated. Elgar then writes one of his lovely sequential sections, and once the original theme is re-introduced it quietly sings to slightly different harmonies before the piece comes to a quiet close.

Edward Elgar: Sonatina

Elgar in Turkey

Elgar was working on a Sonatina in 1889, originally composed for his 8-year old niece May Grafton. She was the daughter of Elgar’s favourite sister, Pollie. May was actually living in the Elgar household in Plas Gwyn, their Hereford home. She helped to run the household, and she was particularly important to Edward once Alice died. May was a keen photographer, and many of the images of the composer were taken by her.

Only in 1932 did Elgar work on these old piano sketches and he completed the Sonatina, which was published in the same year. The Sonatina is a short work in two movements. According to notes from the Elgar Society, “it contains a sentimental, gently rocking melody that gives way briefly to a tiny contrasting section before reverting to the repeated first section.” The second movement is a more cheerful movement that happily dashes to the finish.

Edward Elgar: Minuet

Nicholas Kilburn

Nicholas Kilburn was an iron merchant in Sunderland who was also an amateur conductor and an early champion of Elgar’s work. In fact, he directed all of Elgar’s choral works after 1887 and Elgar referred to him as “The Saint.” Kilburn almost made it into the Enigma Variations, as there is a fragment of a variation that is headed “Kilburn.” In the event, it was Nicholas’ son Paul that the Minuet of 1897 was written for.

This charming piece of music unfold in the form of an arch, as the opening musical turn of phrase keeps returning in the form of a refrain, with a gentle and pastoral melody as the central pillar. Elgar later orchestrated the piece and it was published in its orchestral form in 1897. In the same year, it also appeared as a piano work in “The Dome Magazine,” a publication advertised as “An Illustrated Monthly Magazine and Review of Literature, Music, Architecture and the Graphic Arts.”

Edward Elgar: Concert Allegro, Op. 46

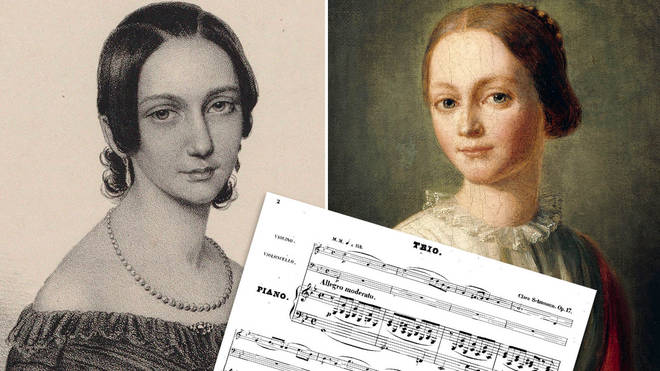

Fanny Davies

The concert pianist Fanny Davies was a student of Clara Schuman and a friend of Johannes Brahms. For many years Elgar had been thinking of writing a piano concerto, but this project never went beyond some sketches. Davies wrote to Elgar in 1901, “I am so disappointed if you can’t let me have just a wee ‘little Elgar’ for my recital on Dec. 2nd … I could learn it very quickly if I had it – and the Concert is not till December 2nd.”

Elgar went to work and produced the Concert Allegro, originally titled “Concerto (without Orchestra) for pianoforte.” Critics were not enthusiastic, and there seems to be the suggestion that Davies played the piece as “anything down to half speed.” Publishers also didn’t want to take on the piece, and many adjustments and amendments were made, including pasting over some original ones. Fanny Davies did continue to perform it, and Richter exclaimed that the work was “as if Bach had married Liszt!” There was some talk of an orchestral arrangement, but the score disappeared and was only rediscovered in 1968.

Edward Elgar: In Smyrna

In the autumn of 1905, Elgar took his friend Frank Schuster on a Mediterranean cruise on the Royal Navy ship HMS Surprise. Elgar went as a guest of the Navy, and he was hosted by Vice-Admiral Beresford. In his diaries Elgar described the journey in great detail, and he was enthused by several places he visited. Among them was the ancient Greek city of Smyrna, currently the Turkish city of Izmir. Elgar noted in his diary, “drove to the Mosque of dancing dervishes … music by five or six people very strange & some of it quite beautiful – incessant drums and cymbals (small) thro’ the quick movements.”

Elgar’s music for “In Smyrna” does not reflect the dervish dances, but rather mirrors an earlier diary entry where he wrote, “Rose late. Very, very hot & sirocco blowing-peculiar feelings of intense heat and wind…” The shimmering qualities are beautifully transferred to the piano and since there are no major climaxes, the work ends quietly. Elgar used some of the materials in his “Crown of India Suite” in 1912.

Edward Elgar: Dream Children, Op. 43

The two movements of “Dream Children” were written in 1902 for either piano or for orchestra. These pieces suggest a strong nostalgia for childhood, as the score is headed by a quotation from Charles Lamb’s Dream-Children, a Reverie. “And while I stood gazing, both the children gradually grew fainter to my view, receding, and still receding till nothing at last but two mournful features were seen in the uttermost distance.”

Capturing wistful innocence was one of the hallmarks of Elgar’s compositional style, and the composer’s DNA is readily found in these piano miniatures. Elgar did produce a piano arrangement of the famed Enigma Variations, but I decided to focus on smaller pieces instead. Of course, Elgar also wrote a number of songs for voice and piano. Would you be interested to have them featured? Please let us know in the comments.