by Emily E. Hogsta

The great composers also experienced a wide variety of Christmas celebrations. Today, we’re looking at five memorable Christmases from the lives of five great composers. (Read Part 1 here: The Most Memorable Composer Christmases: Chopin, Schumann, and More)

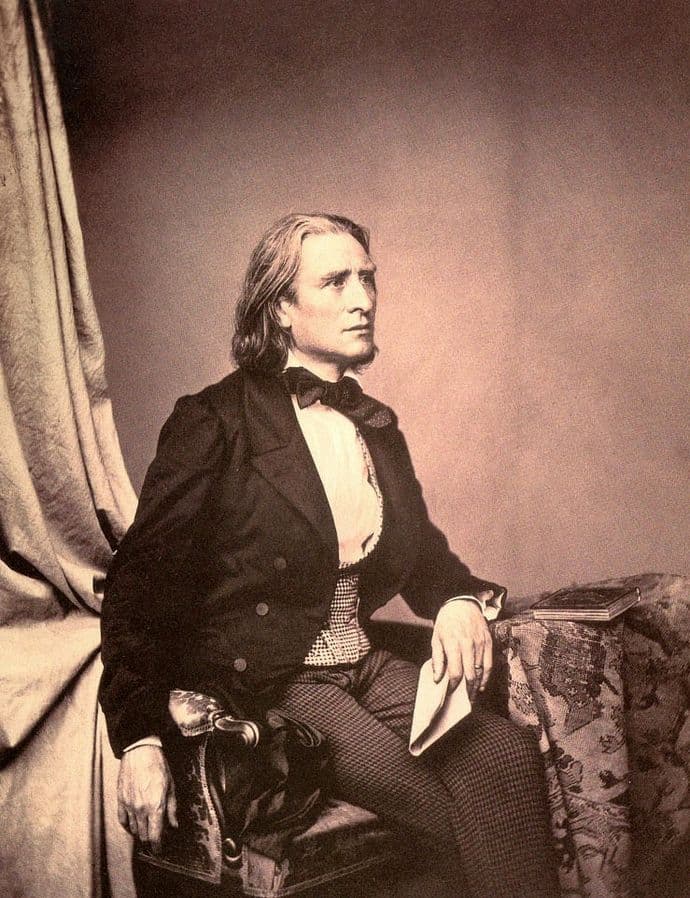

Mahler’s Devastating Breakup – 1884

Gustav Mahler

In mid-1883, 23-year-old Gustav Mahler took a job conducting opera at the Königliches Theater in Kassel, Germany.

While there, he began working with 25-year-old coloratura soprano Johanna Richter and fell in love with her. It was his first intense love affair.

We are not sure if Richter reciprocated Mahler’s feelings quite as intensely; only one letter from her survives.

In 1884, he began composing for her, writing lyrics based on folksongs and setting them to music. He called the resulting song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, or Songs of a Wayfarer. His December 1884 was absorbed by the project.

Despite his passion for Richter, the couple was ultimately doomed.

He spent New Year’s Eve of 1884 with her and wrote to a friend about the experience:

I spent yesterday evening alone with her, both of us silently awaiting the arrival of the new year.

Her thoughts did not linger over the present, and when the clock struck midnight, and tears gushed from her eyes, I felt terrible that I, I was not allowed to dry them.

She went into the adjacent room and stood for a moment in silence at the window, and when she returned, silently weeping, a sense of inexpressible anguish had arisen between us like an everlasting partition wall, and there was nothing I could do but press her hand and leave.

As I came outside, the bells were ringing, and the solemn chorale could be heard from the tower.

Although the relationship didn’t work out, Mahler did reuse ideas from Songs of a Wayfarer in his first symphony, which he composed between 1887 and 1888. He wasn’t about to let his holiday heartbreak go to waste!

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel Is Disappointed by the Christmas Singing of Papal Singers – 1839

Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel

Felix Mendelssohn and his sister Fanny Mendelssohn were two of the most talented child prodigies in the history of music. They remained close for their entire lives.

Felix, however, was encouraged to pursue a musical career, while Fanny’s musical accomplishments were viewed as mere feminine adornments. (Luckily, her husband understood her talent and encouraged her music-making.)

Long story short, Felix got support that she never did, and in 1830, when Fanny was 24, and Felix was 21, the family sent him on a ten-month trip to Italy…without Fanny. The trip was formative, and Fanny was fascinated by the stories of his travels.

Happily, Fanny got to go eventually. Between 1839 and 1840, Fanny, her husband, and her baby son Sebastian took their own trip to Italy, following in Felix’s footsteps.

On 1 January 1840, she wrote to her brother, sharing some observations about musical life in Rome:

We’re enjoying a pleasant life here. We have a comfortable, sunny apartment and thus far have enjoyed the nicest weather almost continuously. And since we’re in no particular hurry, we’ve been viewing the attractions of Rome at our leisure, little by little.

It’s only in the realm of music, however, that I haven’t experienced anything edifying since I’ve been in Italy.

I heard the Papal singers 3 times – once in the Sistine Chapel on the first Sunday in Advent, once in the same place on Christmas Eve, and once in St. Peter’s basilica on Christmas day – and have to report that I was astounded that the performances were far from perfect.

Right now, they seem to lack good voices and sing completely out of tune…

One can’t part with one’s trained conceptions so easily.

Church music in Germany, performed with a chorus consisting of a few hundred singers and a suitably large orchestra, assaults both the ear and the memory in such a way that, in comparison, the pair of singers here seemed quite thin in the wide expanses of St. Peter’s.

With respect to the music, a few passages stood out as particularly beautiful. On Christmas Eve, for instance, after the parts had dragged on separately for a long time, there was a lively, 4-part fugal passage in A-minor that was very nice.

I later discovered that it began precisely at the moment when the Pope entered the chapel, and I didn’t know it at the time because women, unfortunately, are placed in a section behind a grille from which they cannot see anything.

This section is far away, and in addition, the air is darkened by the smoke from candles and incense.

On the other hand, I could at least occasionally see the officials on Christmas day in St. Peter’s very well, and found them quite splendid and amusing.

We naturally had a Christmas tree, because of Sebastian, and constructed it out of cypress, myrtle, and orange branches. The branches were very lovely, but it wasn’t the best-looking tree, and Sebastian and I attempted to outdo each other the entire day in feeling homesick.

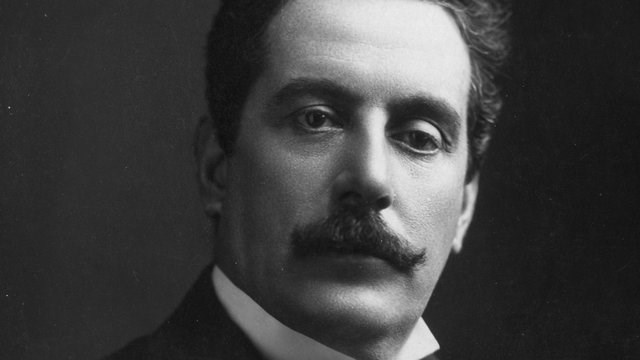

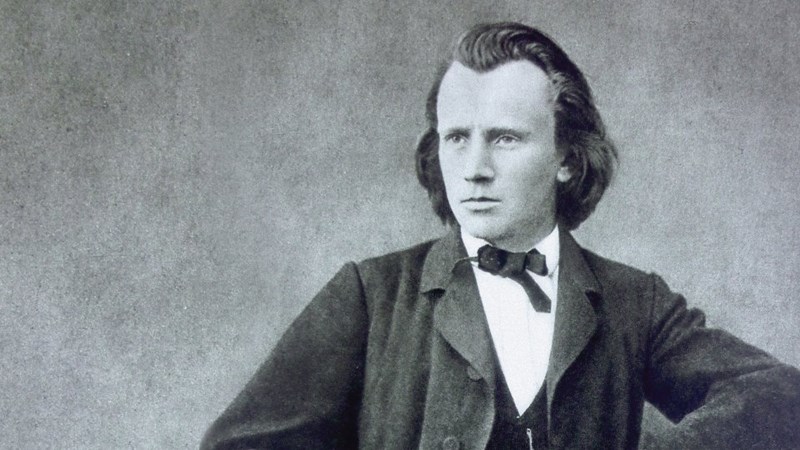

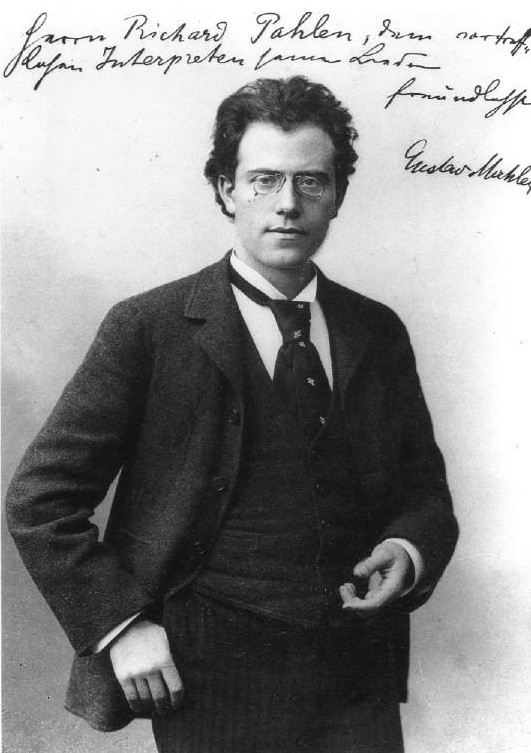

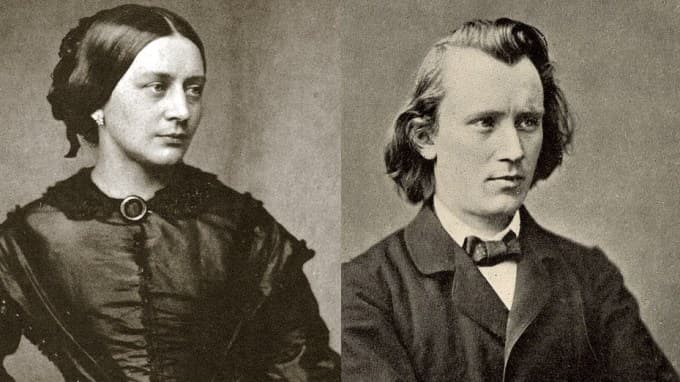

Johannes Brahms Surprises Clara Schumann – 1865

Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms and Robert Schumann’s wife, virtuoso pianist Clara Schumann, stayed close friends until the end of their lives.

They never had a traditional romance, but they loved each other deeply, and over their decades-long relationship, Brahms spent many holidays with Clara and her children.

At Christmas 1865, Johannes was 32, and Clara was 46. Both had busy performing careers that necessitated frequent travel, and Clara assumed that she wouldn’t be seeing Johannes for the holidays.

She sent him a traveling bag as a Christmas gift. With the gift, she included a letter talking about her daughter Julie, who had recently been ill.

She wrote, “Thank heaven we have fairly good news of Julie. She has got over the danger of typhoid, but it will be a long time before she has completely recovered.”

The family was worried about Julie’s health, and they didn’t even bother lighting candles on the tree that year.

But then the door opened – and Brahms appeared! He had made a seven-hour journey to Düsseldorf to surprise the family and check in on Julie himself.

Clara wrote in her diary that she was “very pleased and excited.”

Read our article about Christmas with Brahms.

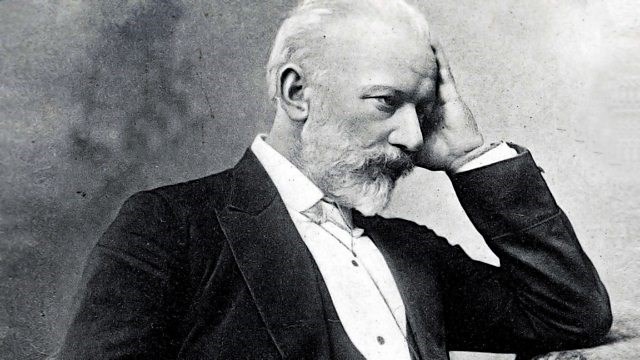

Rachmaninoff Flees Russia – 1917

Kubey-Rembrandt Studios: Sergei Rachmaninoff, 1921

The Russian Revolution began in February 1917, leading to Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication in March and a provisional government taking power.

During that year’s October Revolution, a Bolshevik insurrection overthrew the provisional government. Once the Bolsheviks took power, a broader civil war broke out.

The conflict impacted Rachmaninoff’s life deeply. In the spring of 1917, he returned from touring to find that his estate had been seized by the Social Revolutionary Party. He departed, disgusted, and vowed never to return.

He and his family moved to Moscow. As tensions rose throughout the fall, he made edits to his first piano concerto with the sound of bullets flying in the background.

During this tense time, he received an invitation to give a series of recitals in Scandinavia. He accepted because it would give him and his family an excuse to flee the country.

On 22 December 1917, the Rachmaninoffs got on a train in St. Petersburg, crowded with terrified passengers who feared arrest. Fortunately, the officials who met them were kind.

The following day, they arrived at the Finnish border. To get across it, Rachmaninoff, his wife, and two daughters had to travel in an open peasant sleigh during a blizzard.

They arrived in Stockholm on Christmas Eve. Exhausted, the family stayed in their hotel.

After escaping Russia, Rachmaninoff would go on to a celebrated performing career, but he would compose less and less. Later in his life, he would remark, “I left behind my desire to compose: losing my country, I lost myself also.”

Leonard Bernstein Conducts the Historic Berlin Wall Concert – 1989

Leonard Bernstein

In November 1989, the Berlin Wall was taken down, signaling the demise of the so-called Iron Curtain that had hung across Europe for a generation.

Conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein helped to organise a performance at the present-day Konzerthaus Berlin. This venue had been burned out during World War II but was reconstructed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, opening just a few years before this concert.

Musicians from all around the world participated, including men and women from Leningrad, Dresden, New York, London, and Paris.

Together on Christmas Day 1989, they performed a concert celebrating the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Bernstein programmed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and changed the Ode to Joy to the Ode to Freedom.

It was broadcast all over the world and became one of the most famous orchestral performances of the twentieth century, seen live by around 100 million viewers. How’s that for a memorable Christmas?