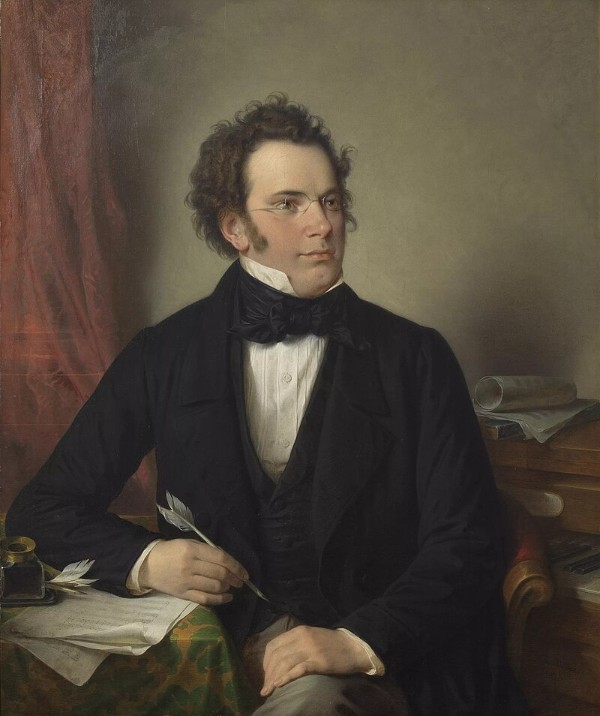

“I am the most unhappy and miserable person in this world… my health will never improve, and in such despair, things will only become worse instead of better…” – Franz Schubert

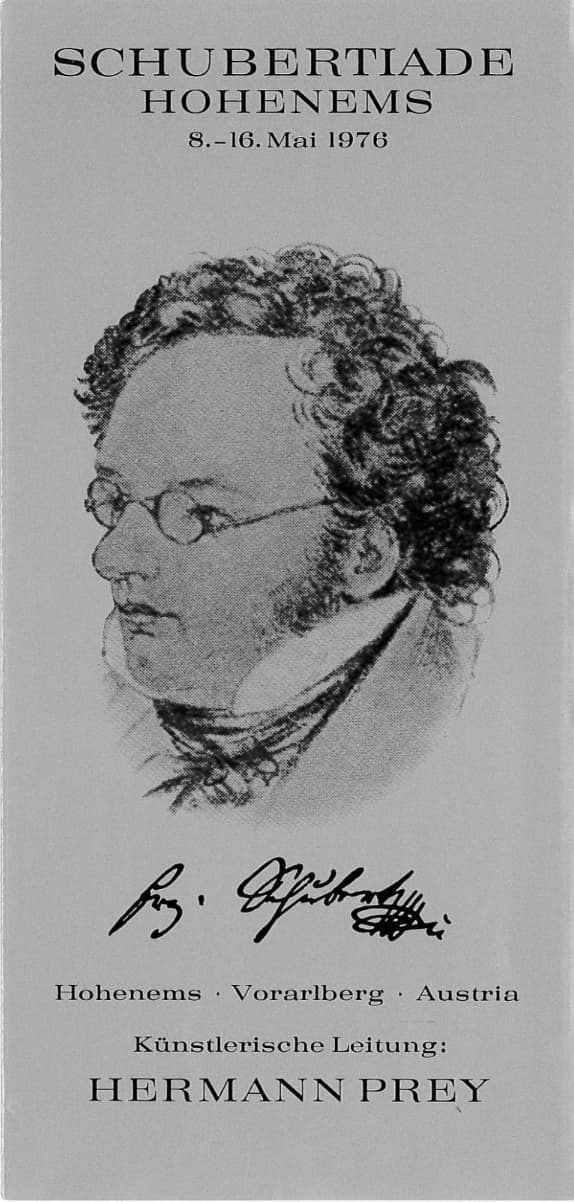

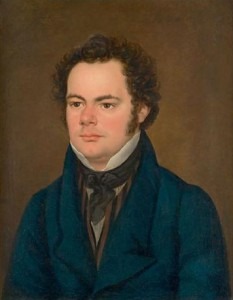

Austrian Composer Franz Schubert (1797-1828) is enshrined as the pillar of Romantic Western Classical Music who follows after Beethoven*. He had completed a tremendous collection of hundreds of lieder, symphonies, operas, and a large body of chamber and piano music that adds up to over 1000 works during his career. This was prolific for a man who only lived for 31 years. Franz Liszt described him as “the most poetic musician who ever lived.” On his deathbed, Beethoven is said to have looked into some of the younger man’s works and exclaimed, “Truly, the spark of divine genius resides in this Schubert!”

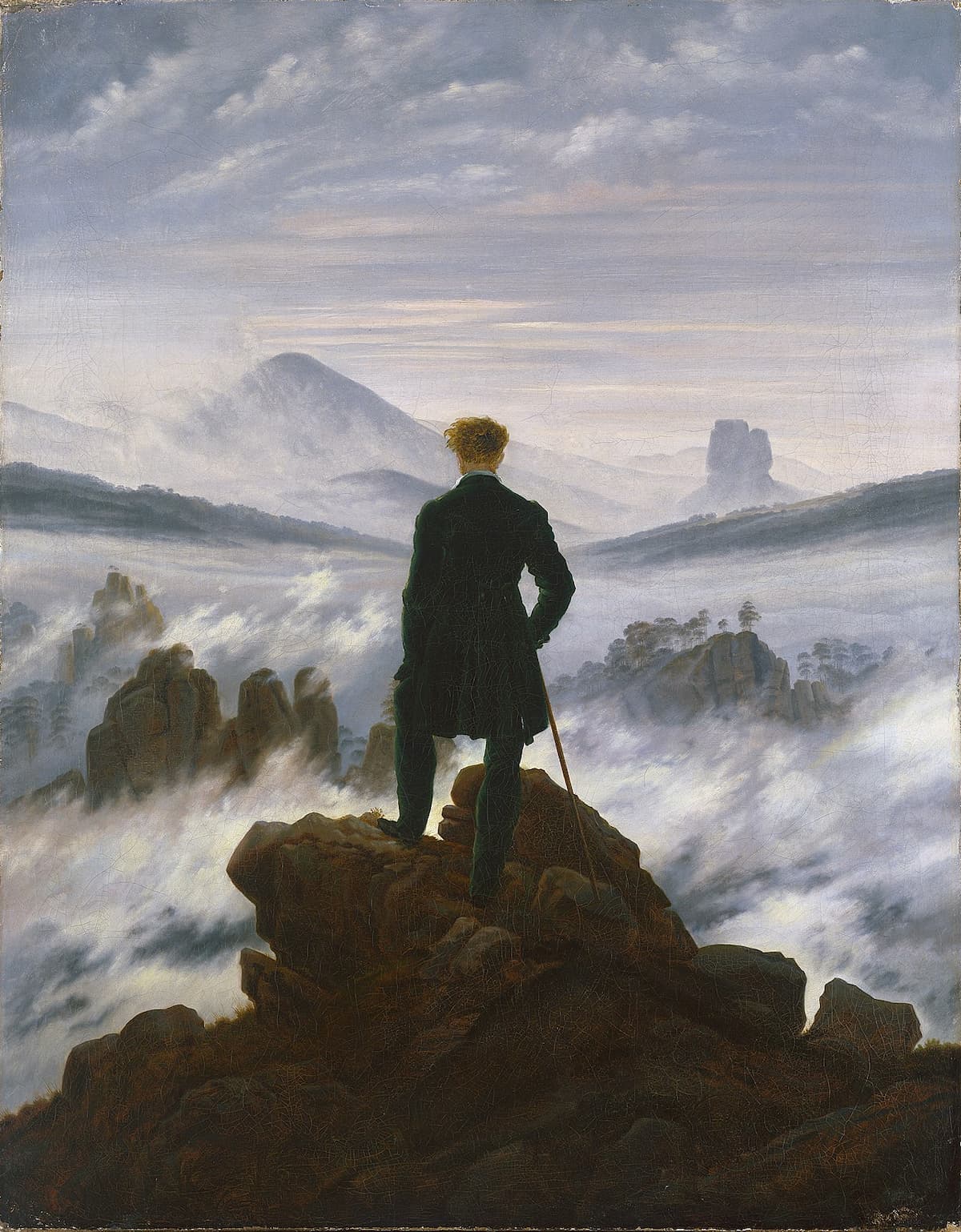

Yet, a number of Schubert’s musical works such as ‘Winter Journey’, ‘the Unfinished Symphony’ and ‘Death and the Maiden’ are said to be filled with elements of death. Indeed, Schubert’s despair during his life is reflected in his own writing, “the brightest hopes have come to naught, to whom the joy of love and friendship can offer nothing but pain at most… Every night as I retire to my bed, I always hope that I would not wake up. Yet every day, the morning breaks into the pains of yesterday’s wounds.”

Why was Schubert so sad?

For most of his adult life, Schubert suffered from cyclothymia, a mental illness that resulted in severe mood swings that fluctuated between hypomanic and depressive episodes. His condition became far more extreme during his mid-twenties, and his friends reported periods of dark despair and violent anger.

For most of his adult life, Schubert suffered from cyclothymia, a mental illness that resulted in severe mood swings that fluctuated between hypomanic and depressive episodes. His condition became far more extreme during his mid-twenties, and his friends reported periods of dark despair and violent anger.

Physically, Schubert’s life was haunted by varying periods of sickness. In 1822, Schubert began to suffer from headaches, intermittent fever and skin rash. The next year, his scalp began to itch so intensely, that he had his patchy head shaved and bought a wig. He was subsequently admitted to Vienna General Hospital, where he wrote part of ‘Die schöne Müllerin’. Hence began the battle with the illness throughout his life.

Schubert was also an introvert personality who was not considered very attractive. Standing at barely five feet tall, he was a shy, stumpy person whose facial features included a round nose, a long oval face and a deeply cleft chin, topped off by very severe short-sightedness. Romance was hence difficult for the composer, and it is said that was why he turned to prostitutes. This may explain why, at the young age of only 21, he had contracted the sexually transmitted disease syphilis. Although syphilis was prevalent in Vienna at that time, the secondary effects of the disease were so stigmatizing that after his death, Schubert’s friends burnt his letters and diaries so that the true nature of his illness could never be officially announced.

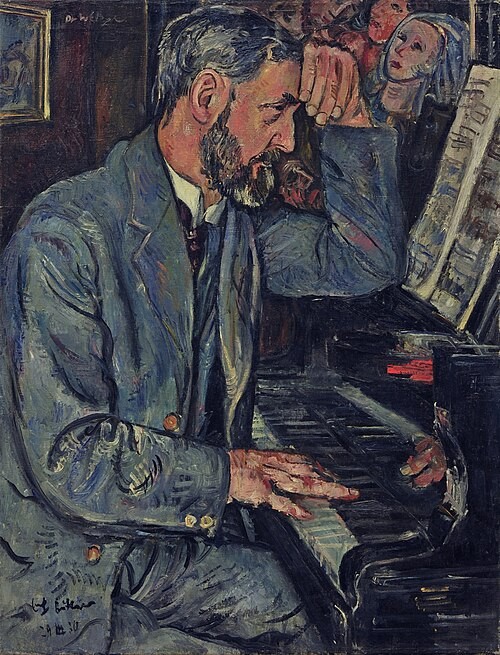

As a composer, Schubert’s work received little recognition during his lifetime. The only two operas he composed were poorly received by the critics. One of them only managed a mere 6 shows before it was forced to close down. Publishers were reluctant to print his works, because he was fairly unknown at the time. As a result, Schubert had no choice but to turn to friends to print his works, but the royalties he could collect were barely enough for even one meal. It was only until Schuman and Franz Liszt performed his work after his death that his work became known.

The Treatment that killed Franz Schubert

In today’s world, people often disregard syphilis, because an early prescription of penicillin is sufficient to treat the condition. Unfortunately for Schubert, the popular treatment by physicians then was to place the patient in a sealed room, and cover the patient’s body with mercury. The patients were therefore forbidden to change their underwear or bed sheets.

The treatment would cause the mouth cavity to heat up and taste of metal, which adversely affected the patient’s appetite. The consequences included mouth cavity pains, difficulty swallowing, excessive drooling, diarrhea, vomiting and excess urination. The doctors explained to the patients that these were simply the side effects of effective treatment. But in fact, these are symptoms of mercury poisoning.

Schubert lived his final days in one of these tightly sealed rooms, and by then he had lost his appetite for more than 10 days. After his death, many articles claim that he died of ‘typhus abdominalis’, but such a disease was not prevalent in Vienna then, nor did he possess the symptoms typical of typhus abdominalis.

Therefore, although Schubert did in fact contract syphilis, it was the mistreatment of his disease that really killed him. Schubert passed away in Vienna in 1828 at the age of only 31.

Music critic Philip Hale’s take on Schubert’s work quite accurately concludes the composer’s life, “when Schubert smelled the mould and knew the earth was impatiently looking for him…it is the melancholy of an autumnal sunset, of the ironical depression due to a burgeoning noon in the spring, the melancholy that comes between the lips of lovers.”