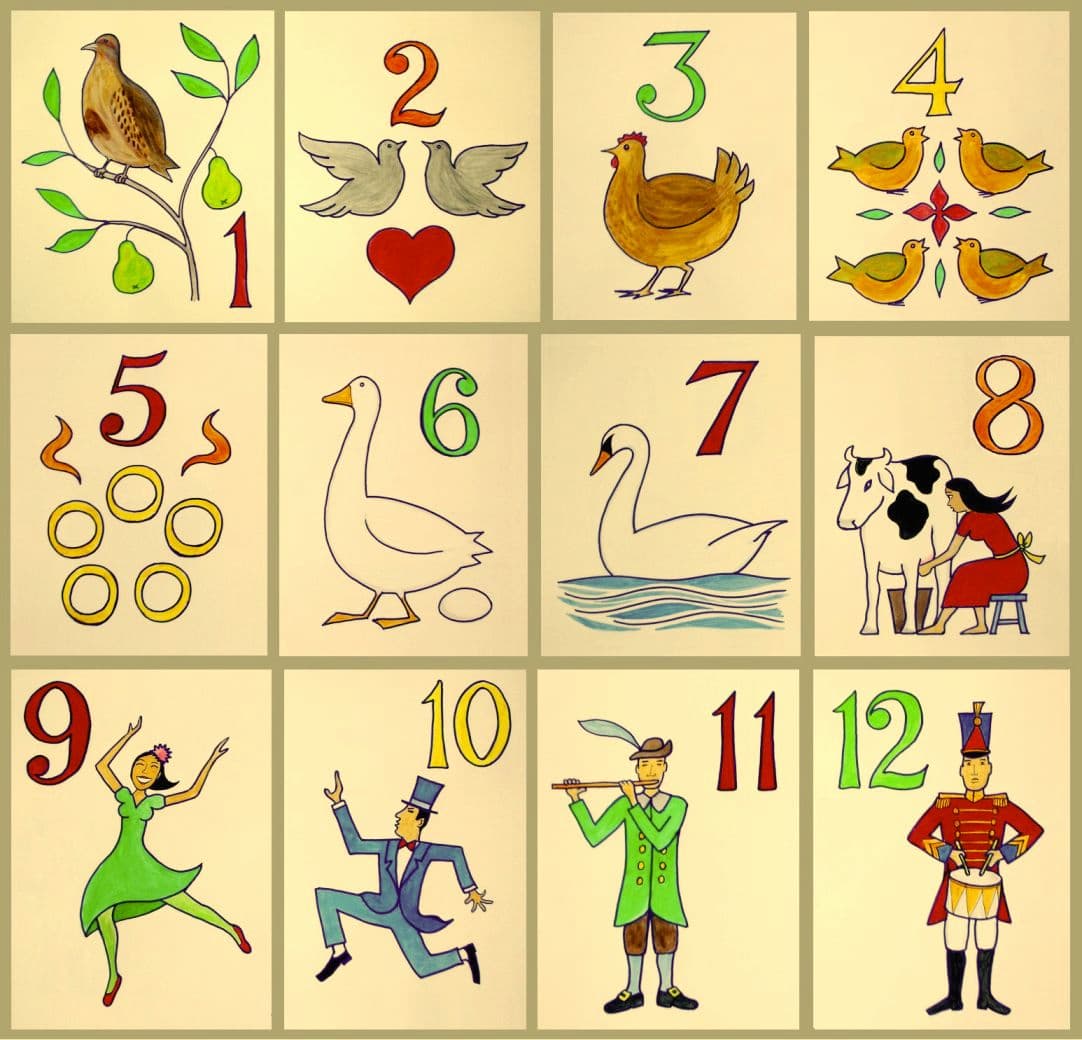

In the new series on dance music, Dance, Dance, Dance, we’ll be looking at dance and how it comes into classical music. You’re going to be surprised at some of the places where it has made an appearance.

We’ll start with not the oldest dances, but with some of the most familiar. In the Baroque era, the dance suite was one of the most popular forms of instrumental music. Pairing of dances was common in the medieval period, but it wasn’t until the 17th century that the keyboard virtuoso Johann Jakob Froberger codified the movements of the suite to include four specific dances: the Allemande, the Courante, the Sarabande, and the Gigue.

Each dance came from a different country and had a different tempo and time signature so that along with the variety of country styles, each dance had its own character.

As its name indicates, the Allemande comes from Germany. It started as a moderate duple-meter dance but came to be one of the most stylized of the Baroque dances. In its earliest versions it was simply called ‘Teutschertanz’ or ‘Dantz’ in Germany and ‘bal todescho’, ‘bal francese’ and ‘tedesco’ in Italy.

It is often paired with a following Courante (from France). When the Allemande was a dance, it was performed by dancers in a line of couples who took hands and then walked the length of the room, walking 3 steps and then balancing on one foot. Musically, the allemande could be quite slow, such as in this piece by Johann Jakob Froberger. Since it was originally intended as a walking piece, the tempo is understandable.

As the century went on, however, the Allemande became faster and eventually functioned like prelude, exploring changing harmonies and moving through dissonances.

In England, the Allemande, or, as it was known there, the Almain or Almand, also became a part of the repertoire. Although this example is short, it could have been repeated multiple times.

By the 18th century, the allemande could get to be quite lively. It has gotten disassociated with its dance and exists solely as a musical form.

In the Baroque suite, the Allemande was followed by the contrasting Courante (from France). The name, derived from the French word for ‘running,’ is a fast dance, performed with running and jumping steps. Following the Allemande in duple meter, the Courente was in triple meter.

In his 17th-century collection Terpsichore, German composer Michael Praetorius collected 312 pieces of dance music, for 3-5 unspecified players. This collection of French dances brought together music of the latest fashion, ‘as played and danced in France’ and that was ‘used at princely banquets or particular entertainments for recreation and enjoyment’. The three courantes here show the different ways one style could be changed.

J.S. Bach used Allemande / Courante pairs in his Partitas and we can hear again that the tempos are contrasting, but really too fast for dancing.

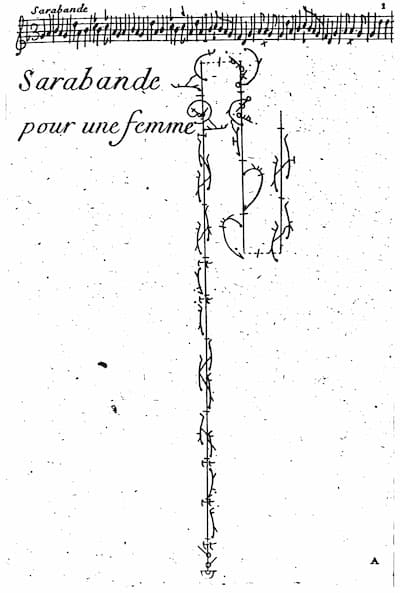

The next dance in the Baroque Suite came from Spain, the Sarabande. It started as a sung dance in Spain and Latin America in the 16th century and by the 17th century, was part of the Spanish guitar repertoire. The Spanish line of development means that it also had Arab influences. As a dance, it was usually created by a double line of couples who played castanets. Once the sarabande got to France, however, what had begun as a fiery couples’ dance changed character completely. It slowed in time, and gradually became a work that might be described as the intellectual core of the Baroque suite.

Fritz Bergen: The Sarabande, 1899

And in a more stately manner:

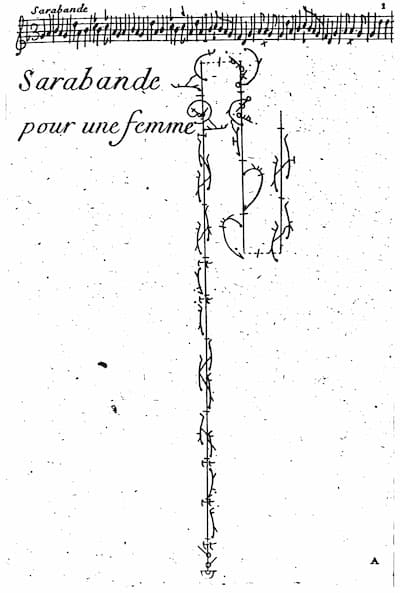

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances: Women’s steps for the beginning of the Sarabande, 1704

The final element of the Baroque dance suite was the English Gigue (or jig). This was a fast dance in 6/8 time that was paired with the slower sarabande. Jigs have been known since the 15th century in England, but as it reached the continent in the 17th, is divided into distinct French and Italian versions. The French gigue was moderately fast with irregular phrases.

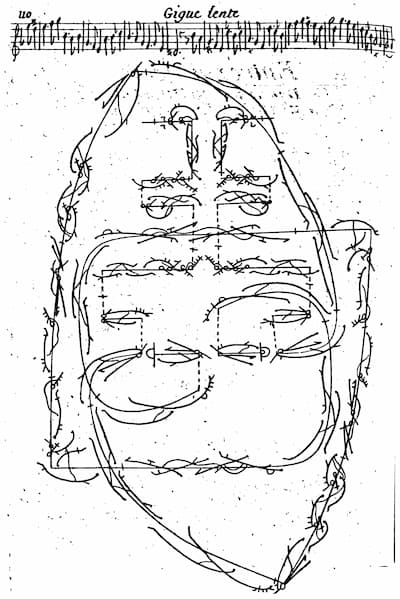

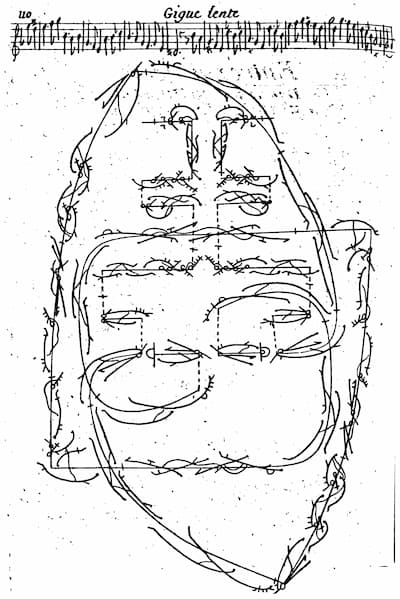

In Feuillet’s and Pécourt’s early 18th century collection, they present the choreography as used in various ballets, mostly by Lully. Here is the middle section of a slow gigue. The two dances start in the center and then move in opposite directions, starting with a large irregularly shaped circling around each other.

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances: Men’s and Women’s steps for the Gigue Lente, 1704

The Italian giga, although it sounded faster than the French gigue, actually had a slower harmonic rhythm. It also didn’t have the irregular phrases of the French model.

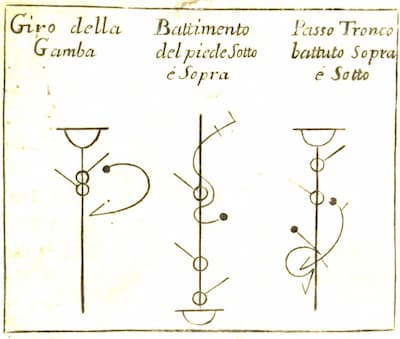

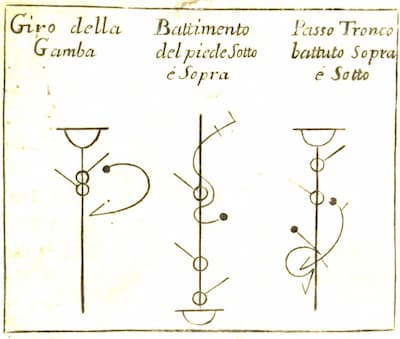

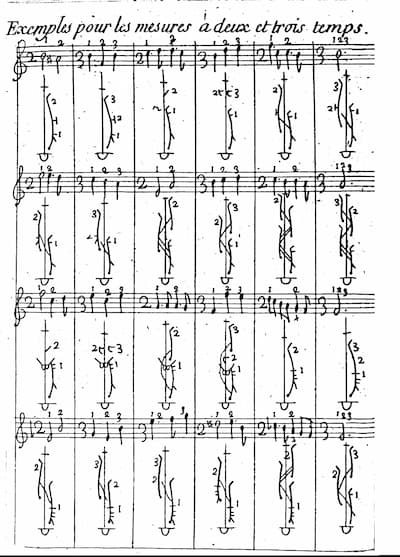

When dances were the social entertainment, there was an enormous business in traveling dancing masters teaching the latest steps, and books published to show how to perform them. This early 18th-century book shows your foot positions, where you turn your leg, where you beat your foot, and bend your knee while your leg is in the air.

Dufort: Trattato el ballo nobile, 1728

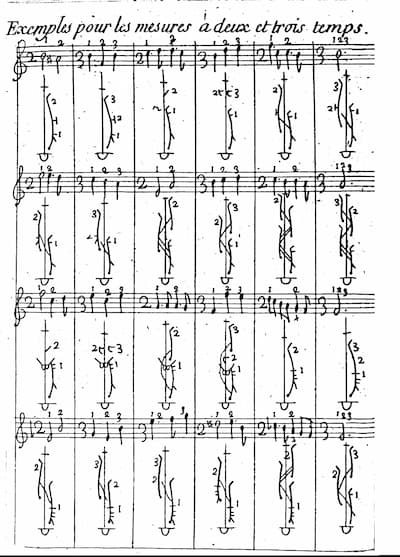

In this more elaborate image from Raoul-Auger Feuillet and Guillaume Louis Pécourt’s 1704 book Recüeil de dances, they give examples of foot movements based on the musical rhythm.

Feuillet and Pécourt: Recüeil de dances, 1704

By the 18th century, the dancing manuals were decrying the introduction of ballet steps onto the dance floor. One 1818 manual asks that dancers be more aware of what they are doing: ‘The chaste minuet is banished; and, in place of dignity and grace, we behold strange wheelings upon one leg, stretching out the other till our eye meets the garter; and a variety of endless contortions, fitter for the zenana of an eastern satrap, or the gardens of Mahomet, than the ball-room of an Englishwoman of quality and virtue.’ In 1875, an American dance manual starts out with the plain declaration that ‘The dance of society, as at present practiced, is essentially different from that of the theatre, and it is proper that it should be so. The former, consisting of movements at once easy, natural, modest and graceful, affords an exercise sufficiently agreeable to render it conducive to health and pleasure. The latter…requires in its classic poses, poetical movement, and almost supernatural strength and agility, too much study and strain…to admit of its performance off the stage…’

As these dance works entered the instrumental repertoire and took to the concert stage versus the dance floor, they became disassociated from their dances – their tempos changed so as to be undanceable and it is the contrast between movements that become the focus: duple or triple meter? Fast or slow tempo? In the next parts we will look at other dance movements, some from the Baroque and others more familiar from the Classical and Romantic repertoire.