Born in the 2000s, these eight performers have already proven their mettle, winning major international competitions, signing with top global labels, and appearing with leading orchestras across Europe, Asia, and America.

Their early careers are providing a real-time glimpse into the future of the art and answering the age-old question: Is classical music in good hands?

The evidence suggests the answer is yes.

Today, we’re looking at eight of the most exciting young classical talents of the century – so far.

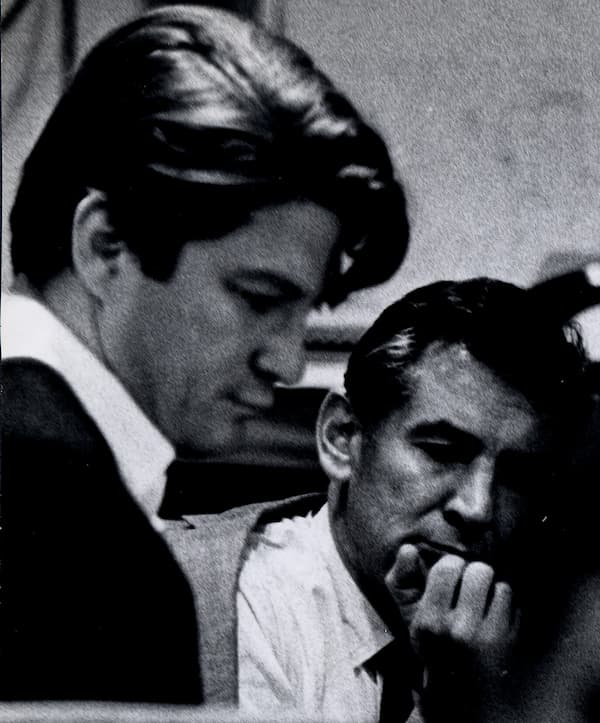

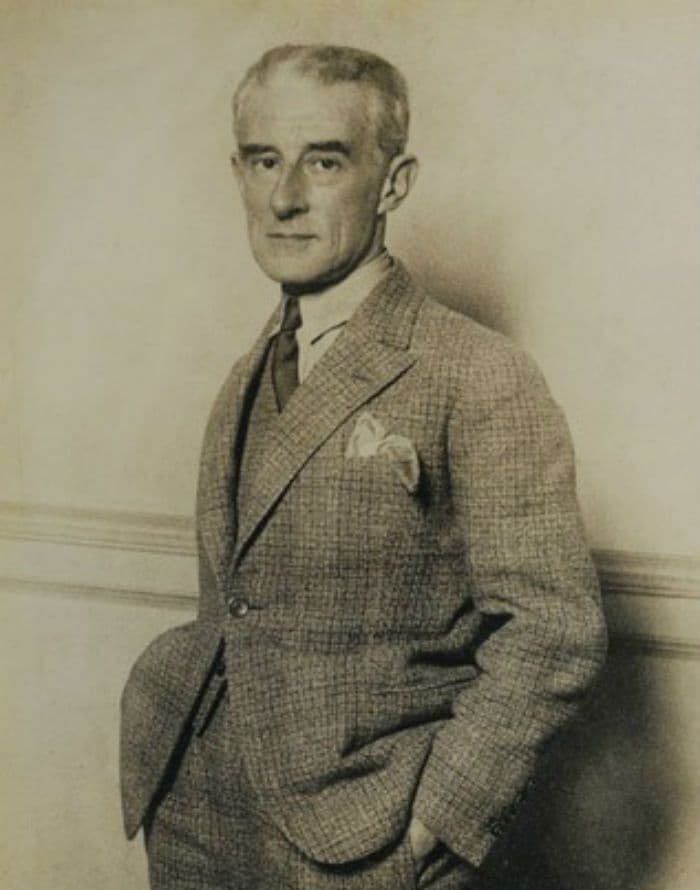

Nicolò Foron (b. 2000) – Conductor

German-Italian musician Nicolò Foron is best-known for his conducting, but he is also a pianist and composer.

In 2021, at the age of 21, he won the Jeunesses Musicales Conducting Competition in Bucharest.

The following year, he was named a conducting fellow at the Tanglewood Festival.

Two years after that, he won the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition, a prestigious event previously won by young star conductors Fabien Gabel and Elim Chan.

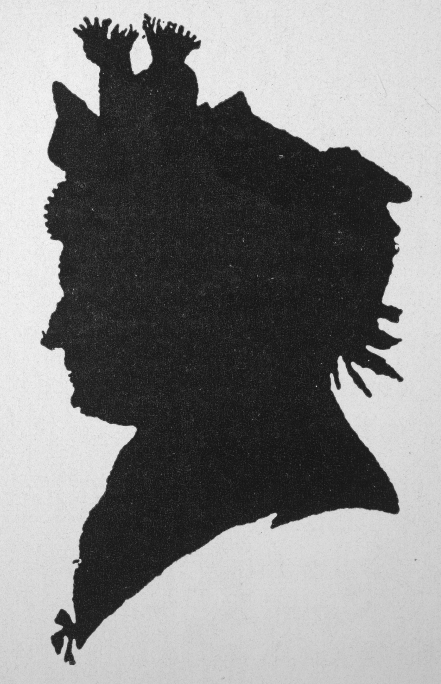

Nicolò Foron

As part of his Flick Competition win, he was named the Assistant Conductor at the London Symphony Orchestra.

In 2025, he conducted both the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. More prestigious debuts are on the horizon.

Critics have taken note of Foron’s unusual but effective stage presence. During the Donatella Flick competition, reviewer Lawrence Dunn wrote for Bachtrack: https://bachtrack.com/feature-pressure-intoxication-donatella-flick-lso-conducting-competition-march-2023

“Foron doesn’t look like the typical conductor. He is more a mixture of a mathematics graduate student and a bank manager’s son. But he has a clear charisma of his own… He is going places.”

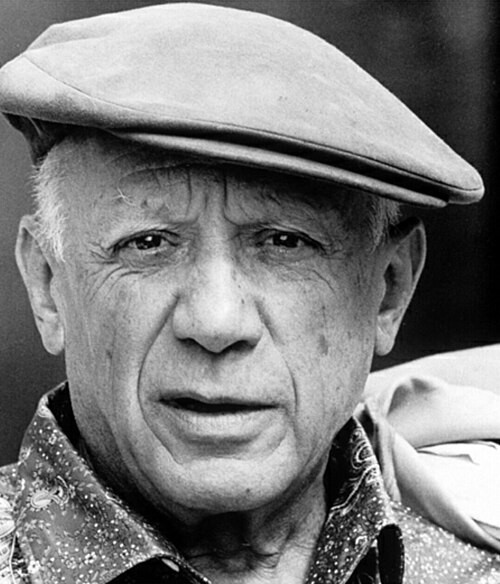

María Dueñas (b. 2002) – Violin

María Dueñas was born in 2002 in Granada, Spain. Although there are no musicians in her family, she went with them to concerts from an early age and began playing the violin at the age of seven.

She studied in Dresden before enrolling at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna and at the University of Graz.

In 2021, she won the first prize and audience prize in the Senior Division at the Menuhin Competition.

The following year, she was signed to the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon label. Since signing, she has recorded an impressively wide range of repertoire.

María Dueñas

Her recordings include the Beethoven violin concerto with multiple cadenzas from a variety of composers, virtuosic caprices by Paganini and other Romantic Era violin greats, and a concerto by contemporary composer Gabriela Ortiz.

In addition to her violin career, she is also a talented pianist and composer.

Yoav Levanon (b. 2004) – Piano

Yoav Levanon was born in Israel. His mother was a professional violinist and had an upright piano at home that Levanon began to play when he was three.

As a child, he made his orchestral debut with the Israel Chamber Orchestra, and in 2018, he performed Rachmaninoff’s second concerto with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

In the summer of 2019, when he was just fifteen, Levanon appeared at the prestigious Verbier Festival in Switzerland. He was the youngest pianist to ever appear there and was nicknamed “the little prince of the piano” by Le Temps.

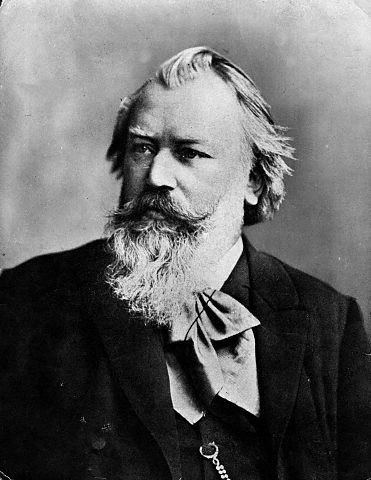

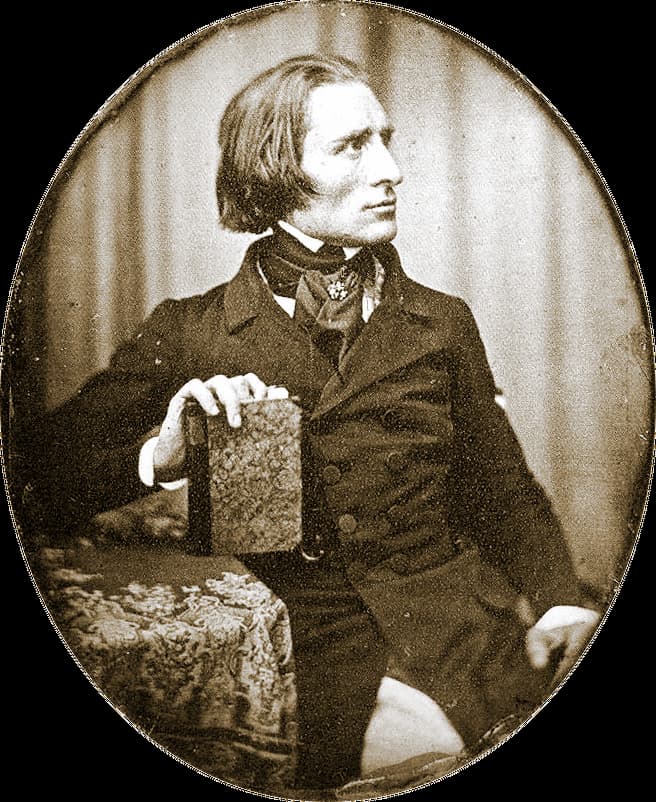

Yoav Levanon

In 2021, he signed a record deal with Warner Classics. He has since released albums with repertoire by Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Chopin, Mendelssohn, and Schumann.

We talked to Yoav Levanon in late 2024 about his background, what Liszt’s music means to him, and what it’s really like recording with an orchestra.

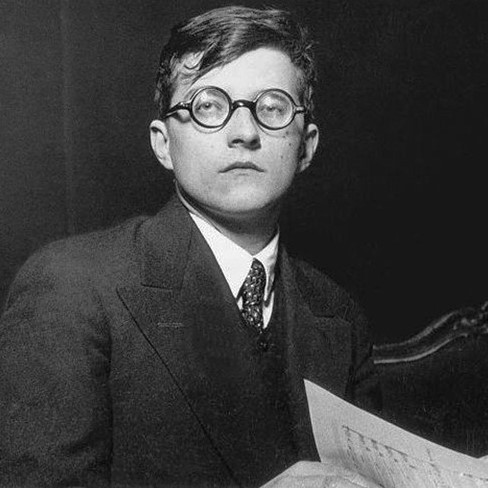

Yunchan Lim (b. 2004) – Piano

Korean pianist Yunchan Lim began piano lessons at the age of seven, entering the Music Academy of Seoul Arts Center the following year.

He attended the Yewon School and the Korea National University of Arts, studying under pianist Minsoo Sohn. Later, he followed Minsoo Sohn to the New England Conservatory of Music, where, as of 2025, he still takes lessons.

He won or placed at a number of competitions during his teens, including the Second Prize at the Cleveland International Piano Competition in 2018 when he was just fourteen.

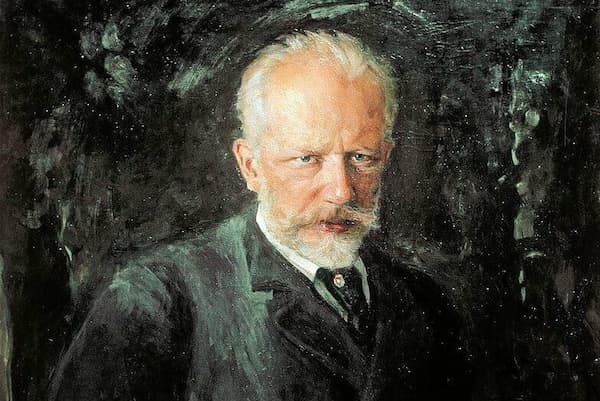

Yunchan Lim

However, his big break came in the summer of 2022, when he won the gold medal at the Van Cliburn Competition. He was just eighteen and became the youngest person to ever achieve this feat.

His performance of Rachmaninoff’s third piano concerto from the final stage of the Cliburn went viral, earning millions upon millions of views.

He has since become one of the leading soloists in the classical music world. His style merges a modern machine-like virtuosity with a deep love of the instrument and an obsessive fascination with early twentieth-century performance traditions.

Jaemin Han (b. 2006) – Cello

Jaemin Han, a frequent chamber music collaborator of Yunchan Lim’s, was born in South Korea to a family of musicians.

He began playing cello at the age of five and made his orchestral debut at the age of eight.

He won his first major competition in 2015 when he won first prize at the Osaka International Music Competition.

Jaemin Han

In 2021, he became the youngest person to ever win the Grand Prix of the George Enescu International Competition.

He has also won prizes at the Geneva International Music Competition and I SANGYUN Competition.

Although he’s still in his teens, he has played with major orchestras all around the world, including the Seoul Philharmonic and the Orchestre de Paris, and under the batons of major conductors, including Jaap van Zweden and Myung-Whun Chung.

His tone is muscular and his musicality strikingly mature, while his assured stage presence and clear comfort with performing draw his audiences in.

Chloe Chua (b. 2007) – Violin

Chloe Chua is the daughter of a music educator, who started her on piano at two and a half and violin at four.

From the age of four until seventeen, she studied at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in Singapore. As of 2025, she studies at the Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin.

Chloe Chua

In 2018, the year she turned eleven, she won first prize in the Junior division of the Menuhin Competition.

Her performances from the competition went viral on YouTube, boosted by a reaction video by well-known YouTube videomakers TwoSet Violin. (She has since appeared on their channel multiple times.)

Is Ling Ling a GIRL?

Between 2022 and 2024, she appeared as the Artist-In-Residence at the Singapore Symphony.

She has recorded music by Vivaldi, Locatelli, Paganini, and Mozart.

Her playing is noted for its old-soul maturity, refinement, and sheer beauty of sound.

Amaryn Olmeda (b. 2008) – Violin

Amaryn Olmeda was born in Melbourne, Australia, before moving to California. As a child, she enrolled at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where, at the age of thirteen, she joined an apprentice program co-sponsored by the Conservatory and Opus 3 Artists.

That same year, she won first prize at the 2021 Sphinx Competition.

In 2022, when she was fourteen, she debuted at Carnegie Hall, performing on the Sphinx Virtuosi tour.

Over the next few years, she appeared with a number of major orchestras.

As of 2025, she is studying at the New England Conservatory of Music.

Amaryn Olmeda

In the words of Classical Voice North America, “Olmeda is clearly on her way to a stellar career. Combining a charismatic stage presence and audience appeal with pinpoint intonation, intense lyricism, and fluid technique…she is here to stay.”

Tianyao Lyu (b. 2008) – Piano

Tianyao Lyu was born in October 2008 in China.

She studied with Hya Chang at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, and as of 2025, is studying with Katarzyna Popowa-Zydroń at the Poznań Academy of Music in Poland.

In 2024, she won first prize at the International Ettlingen Competition in Germany.

But her biggest success to date came in October 2025, when she competed against pianists nearly twice her age at the Chopin International Competition, arguably the most prestigious piano competition in the world.

She became beloved by viewers internationally for her fearless poise and the skill and purity of her playing.

Tianyao Lyu

After three weeks of intense competition, Tianyao Lyu emerged with a 4th Prize, as well as a Best Concerto Performance prize. The results were delivered on her seventeenth birthday.

Even though she didn’t win, a sizable contingent of fans believes she was the true breakout star of the event. And because of her youth, she has the chance to come back multiple times in the future to try to nab first prize, should she ever wish to try.

Conclusion

These remarkable musicians underscore how classical music’s future is both vibrant and international.

Each of them – whether they’re winning major competitions, signing major recording contracts, or captivating millions online in their viral videos – has already established a distinctive artistic identity, and they’re only getting started.

Following their careers is going to be a major thrill and honour for every classical music lover.

Taken together, all eight of these musicians prove that the future of classical music is in capable, inspiring, and unnervingly talented hands.