by

Can you imagine a world where jagged geometric shapes dance to the swelling strings of a symphony orchestra? That’s the unlikely yet captivating intersection of Pablo Picasso and classical music.

Picasso, the Spanish maestro of modern art, revolutionised painting with his Cubist explosions, but his life was equally tuned to the rhythms of Stravinsky, the melodies of Satie, and the operatic arias of his era.

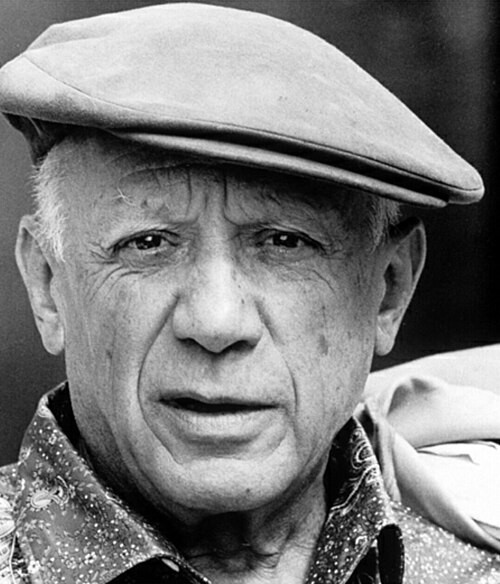

Pablo Picasso

Far from a mere backdrop, music was Picasso’s muse, collaborator, and even co-conspirator in defying artistic norms. To celebrate his birthday on 25 October, let’s explore how his canvases echoed symphonic structure and what composers inspired his brushstrokes.

Erik Satie: Parade

Cabaret Rhythms and Salon Symphonies

Picasso’s relationship with music began in his bohemian youth in late 19th-century Barcelona and Paris. Born on 25 October 1881, he grew up in a Spain where flamenco guitars twanged alongside Wagnerian operas seeping in from Europe.

As a young artist in the Montmartre cabarets, Picasso immersed himself in the sounds of his time, listening to the ragtime jazz creeping from America, but more profoundly to the classical repertoire that filled Parisian salons.

He was no passive listener as music shaped his creative process. Friends recalled him humming arias while sketching, his studio often alive with phonograph records spinning Debussy’s impressionistic waves or Mozart‘s playful minuets.

Montmartre Rag – Mitchell’s Jazz Kings (1922)

Fractured Harmonies

Pablo Picasso: Three Musicians, 1921

In his own words, “Music is something I mistrust intensely. It goes too fast, or perhaps my mind can’t keep up,” yet he could not stay away and doodled musical instruments in notebooks and painted violinists as alter egos.

Around 1907, together with Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso stumbled upon the idea of cubism. This wasn’t just a visual disruption, but it mirrored the fractured harmonies of contemporary music.

Picasso attended the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and the primal rhythms and dissonant clashes are captured in his canvases. Just take his “Three Musicians,” with an angular guitar and clarinet fragments pulsing like atonal motifs.

Visual Echoes

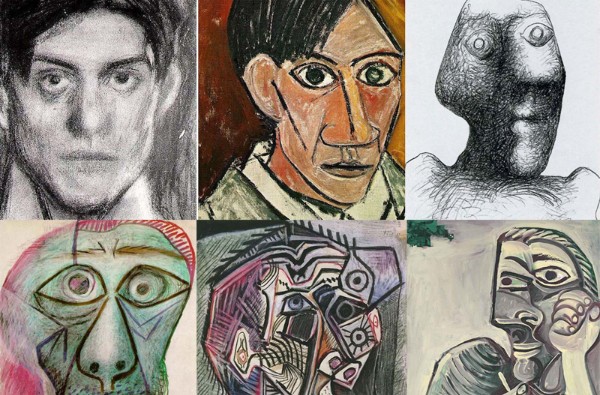

Self portraits of Pablo Picasso

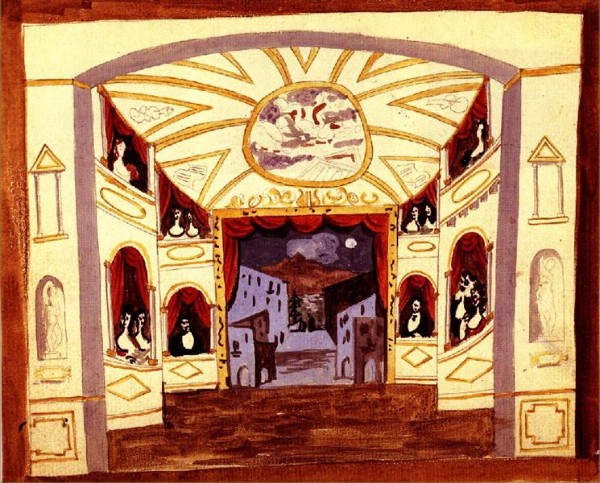

Picasso painted the sound of disruption itself, turning harmony into controlled chaos. He was fascinated by the fusion of art, dance, and music into grand spectacles, and he collaborated with Erik Satie in Parade and with Igor Stravinsky in Pulcinella.

Despite his deep immersion in musical culture, designing sets for various ballets and depicting guitars, harps, and musicians, there is no evidence of Picasso playing a musical instrument.

His engagement with music was primarily auditory, visual, and collaborative rather than performative. And in his own statement, he emphasised his role as a listener and visual y

Synesthetic Rebellion

Pablo Picasso: Mandolin and Guitar

He once described music as “another dimension” of creativity but deferred to specialists, saying in a 1935 interview, “I paint what music sounds like.” Picasso’s instrument was the canvas, as he claimed to hear colours and forms as musical equivalents. As he related to his friend Guillaume Apollinaire, “music and art are the same thing… I start a painting with a rhythm in my head, like a jazz tune.”

There is no evidence that Picasso had a liking for the structured counterpoint of Bach, the elegant gallantries of Mozart, or the heroic symphonism of Beethoven. These impressions clashed with his preference for raw emotion and fragmentation.

He did draw on ancient Greco-Roman forms visually, but musically he stuck to contemporaries over the “old masters.” He certainly did dislike traditional classical ballet and prioritised Spanish vitality over high European canon.

Visceral Visions

Scene design for Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, 1920

Both Picasso and classical music were rule-breakers in eras craving change. Their innovations of dissonance and fragmentation demanded that audiences reassemble the pieces, much like a Rubik’s Cube of sound and sight.

In Picasso’s synesthetic vision, music wasn’t mere accompaniment but a structural force. He orchestrated forms on canvas, layering auditory echoes into visual polyphony. Picasso’s dislike for conventional classical giants like Beethoven stemmed not from disdain but from irrelevance. For him, they lacked the visceral disruption he craved.

Instead, he championed music’s revolutionary edge, suggesting that true creation thrives in sensory rebellion. As Picasso once quipped, “I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them,” much like composers hearing inner symphonies. Picasso didn’t just appreciate classical music; he repainted its soul.

No comments:

Post a Comment