by Georg Predota

“The Professional Dilettante”

Tomaso Albinoni

There is hardly a collection of recorded Baroque favorites that does not include the “Adagio in G minor” by Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1751). Although that world-famous composition is attributed to Albinoni, it was actually the creation of the mid-20th century Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto. While completing his biography on the composer, Giazotto claimed to have found a fragment of an Albinoni composition in an archive of a Germany library. That fragment supposedly contained snippets of a melody and a supporting continuo part. Relying on the stylistic features of the Italian Baroque, Giazotto “completed” the fragment, and the Italian publisher Ricordi published the “Albinoni Adagio” in 1958. So far so good, but there is one more twist to that story, as nobody has been able to locate or examine that mysterious Albinoni fragment. The attribution to Albinoni might be a clever work of fiction, but Tomaso Albinoni did exist, as he was born 350 years ago in the city of Venice.

Remo Giazotto

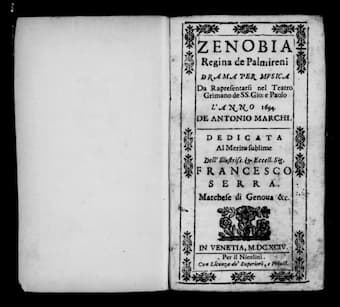

Albinoni’s father was a manufacturer of playing card who owned several shops and some property in Venice. Tomaso was slated to take over his father’s business, but in his spare time he took violin and singing lessons. He obviously was highly talented, but since he was independently wealthy, he never looked for employment in music. Instead, “he preferred to remain a man of independent means who delighted himself and others through music.” Initially, Albinoni dabbled in church music but failed to make a mark. However, he did step into public view at the beginning of 1694, as his first opera Zenobia, regina de Palmireni was staged at the Teatro Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice. Dedicated to his fellow Venetian, the Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, the work was popular and performances continued for several weeks. Concordantly, Albinoni published his 12 Sonatas Op. 1, and it became obvious that “instrumental ensemble music (sonatas and concertos) and secular vocal music (operas and solo cantatas) were to be his two areas of activity in a musical career that lasted the better part of 47 years.”

Frontispiece of Albinoni’s ‘Zenobia’

Albinoni might briefly have served Ferdinando Carlo di Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua, and his hugely popular suites Opus 3 are dedicated to Ferdinando de’Medici, Grand prince of Tuscany. His theatrical works soon began to be staged in other Italian cities. Rodrigo in Algeri was staged in Naples in 1702, and Griselda and Aminta in Florence in 1703. A set of comic intermezzos Vespette e Pimpinone of 1708 proofed especially popular. Albinoni reached the height of his popularity in 1722. He dedicated a set of 12 concertos to Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria. In turn, he was commissioned to compose music for the wedding of Karl Albrecht to Maria Amalia, the younger daughter of the late emperor Joseph I. Albinoni wrote at least fifty operas, of which twenty-eight were produced in Venice between 1723 and 1740. The composer claimed to have created a grand total of 81 operas, but the vast majority of these stage works have been lost because they were not published during his lifetime.

Italian composers Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1750), Domenico Gizzi (Egizio or Egiziello) (1680- c. 1745) and Giuseppe Colla (1731-1806) by Pietro Bettelini (1763–1829)

Although a good many attributions to Albinoni are doubtful, he apparently did compose nearly 50 solo cantatas. However, he is primarily known as a composer of instrumental music, with almost 100 sonatas for between one and six instruments, 59 concertos and 8 sinfonias to his name. His instrumental compositions were published in Italy, Amsterdam and London, and subsequently reissued and reprinted. They were favorably compared to those of Corelli and Vivaldi, and J.S. Bach wrote at least four keyboard fugues on Albinoni themes. We also know that Bach frequently used Albinoni bass lines as foundation for harmonic exercises for his students. Sadly, substantial parts of Albinoni’s works were lost with the destruction of the Dresden State Library in World War II. Albinoni’s music has been criticized “for an over dependence on certain formal stereotypes, and a dryness and lack of harmonic finesse.” It must be said, however, that Albinoni possessed a remarkable melodic gift, and that his mature works “display an almost perfectly realized equilibrium between form and content.” From about 1730, Albinoni gradually withdrew from public life and from composition. He spent the last decade of his life in the care of his three children, and he died on 17 January 1751 from diabetic complications in Venice.

(C) 2021 by Interlude